Published online Dec 28, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i48.7308

Revised: October 25, 2012

Accepted: November 14, 2012

Published online: December 28, 2012

Processing time: 139 Days and 4.1 Hours

AIM: To investigate the short-term outcome of laparoscopic total mesorectal excision (TME) in patients with mid and low rectal cancers.

METHODS: A consecutive series of 138 patients with middle and low rectal cancer were randomly assigned to either the laparoscopic TME (LTME) group or the open TME (OTME) group between September 2008 and July 2011 at the Department of Colorectal Cancer of Shanghai Cancer Center, Fudan University and pathological data, as well as surgical technique were reviewed retrospectively. Short-term clinical and oncological outcome were compared in these two groups. Patients were followed in the outpatient clinic 2 wk after the surgery and then every 3 mo in the first year if no adjuvant chemoradiation was indicated. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13.0 software.

RESULTS: Sixty-seven patients were treated with LTME and 71 patients were treated with OTME (sex ratio 1.3:1 vs 1.29:1, age 58.4 ± 13.6 years vs 59.6 ± 9.4 years, respectively). The resection was considered curative in all cases. The sphincter-preserving rate was 65.7% (44/67) vs 60.6% (43/71), P = 0.046; mean blood loss was 86.9 ± 37.6 mL vs 119.1 ± 32.7 mL, P = 0.018; postoperative analgesia was 2.1 ± 0.6 d vs 3.9 ± 1.8 d, P = 0.008; duration of urinary drainage was 4.7 ± 1.8 d vs 6.9 ± 3.4 d, P = 0.016, respectively. The conversion rate was 2.99%. The complication rate, circumferential margin involvement, distal margins and lymph node yield were similar for both procedures. No port site recurrence, anastomotic recurrence or mortality was observed during a median follow-up period of 21 mo (range: 9-56 mo).

CONCLUSION: Laparoscopic TME is safe and feasible, with an oncological adequacy comparable to the open approach. Further studies with more patients and longer follow-up are needed to confirm the present results.

- Citation: Gong J, Shi DB, Li XX, Cai SJ, Guan ZQ, Xu Y. Short-term outcomes of laparoscopic total mesorectal excision compared to open surgery. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(48): 7308-7313

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i48/7308.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i48.7308

Rectal cancer accounts for approximately half of all colo-rectal cancer cases in China. Significant advances have been achieved in the treatment of rectal cancer in the past few decades. With the introduction of total mesorectal excision (TME), laparoscopic technique, as well as pre- and postoperative chemo-radiotherapy, the local control rate and survival of rectal cancer patients have dramatically improved. The TME principles, which were first described by Heald et al[1], are currently considered the standard practice for mid and low rectal cancer as local recurrence is reduced to less than 5%[2]. A complete TME consists not only of the routine excision of intact mesorectum, but also preservation of the autonomic nervous system and the sphincters.

Laparoscopic surgery has been used in the treatment of colorectal cancer since the end of the 1990s with the purpose of ameliorating postoperative recovery without compromising oncological adequacy. Although laparoscopy in colon cancer has gained acceptance due to its proven benefits[3,4], which include fewer perioperative complications, faster postoperative recovery and comparable survival rates, laparoscopy in rectal cancer is still not recommended as the treatment of choice by National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines. Laparoscopic rectal surgery is more complex and technically demanding, especially for mid and low rectal cancer. As surgical techniques and equipment have developed, the feasibility and safety of laparoscopic TME (LTME) have been reported by many institutes[5,6]. Moreover, long-term survival following LTME seems to be comparable to open TME (OTME)[7,8]. However, there are few well-designed studies which have addressed this particular issue. Most of the randomized clinical trials on rectal cancer were performed in the early 2000s when the laparoscopic rectal surgical technique was still being developed, and the majority of these studies included both colon and sigmoid cancer[9,10]. Thus it is inclusive whether laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer is comparable to open surgery.

The aim of this study was to compare the short-term outcomes of LTME and OTME in mid and low rectal cancers in a series of unselected patients. The primary endpoints were operative details (operating time, blood loss, sphincter preservative rates and conversions), perioperative complications (anastomotic leak, obstruction, and wound infections) and postoperative recovery (urinary function, use of analgesics, and return of bowel movement). The secondary endpoints were pathological evaluations (positive margin involvement, number of lymph nodes harvested and length of inferior margin).

Between September 2008 and July 2011, a consecutive series of 138 patients diagnosed with middle and low rectal cancer underwent surgical treatment at the Department of Colorectal surgery of Shanghai Cancer Center, Fudan University. The diagnosis in these patients was confirmed by a full colonoscopy plus a biopsy. The inclusion criteria were: patients diagnosed with rectal cancer with the tumor located ≤ 10 cm from the anal verge. All patients received a systematic preoperative assessment including physical examination, biochemical analysis and a five-marker panel (carcinoemb- ryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, cancer antigen 724, cancer antigen 242 and cancer antigen 125 for female patients) assay. Chest, abdominal and pelvic computed tomography scans were performed to rule out any pulmonary or liver metastasis. In addition, magnetic resonance imaging or endorectal ultrasound was performed to evaluate the preoperative staging. Patients staged at cT3/4 cTxN+ were assigned to neoadjuvant treatment in the absence of contraindications, and therefore were excluded from this series. The exclusion criteria also comprised patients with a former history of radiotherapy or chemotherapy, patients with distant metastases and patients with contraindication to laparoscopic surgery. An American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade was assigned to each patient by an anesthetist before surgery. Low molecular weight heparin was administered subcutaneously as prophylactic anticoagulant treatment and D-dimer was monitored regularly at day 1, 4 and 7 postoperatively.

Patients were routinely followed in the outpatient clinic 2 wk after e surgery and every 3 mo for the first year, then every 6 mo for the second year, and every year thereafter. If there was an indication for adjuvant chemoradiation, follow-up data was complemented by phone contact with the patients as well as contact with the patients’ current treating physicians. Data were collected and reviewed retrospectively, including patients’ demographics, preoperative staging, surgical technique, pathological evaluations and postoperative recovery.

All patients underwent low anterior resection (LAR) or abdominoperineal resection (APR) according to accepted TME principles. All surgeries were performed by the same team of surgeons with proven expertise in colorectal cancer surgeries who perform more than 100 laparoscopic and open colorectal surgeries annually. All patients were operated on under general anesthesia.

Four trocars were introduced after CO2 pneumoperitoneum was established at 12 to 15 mmHg. A 10-mm port was positioned 0.5 cm above the umbilicus for observation. Another 10-mm port was introduced one-third of the distance from the right anterior superior iliac spine to the navel as the major operative site. Two additional 5-mm ports were placed for assistance. One port was set one-third of the distance from the left anterior superior iliac spine to the navel. The other was positioned at a digit inferior to the umbilicus crossing the left parasternal line reserved for possible colostomy.

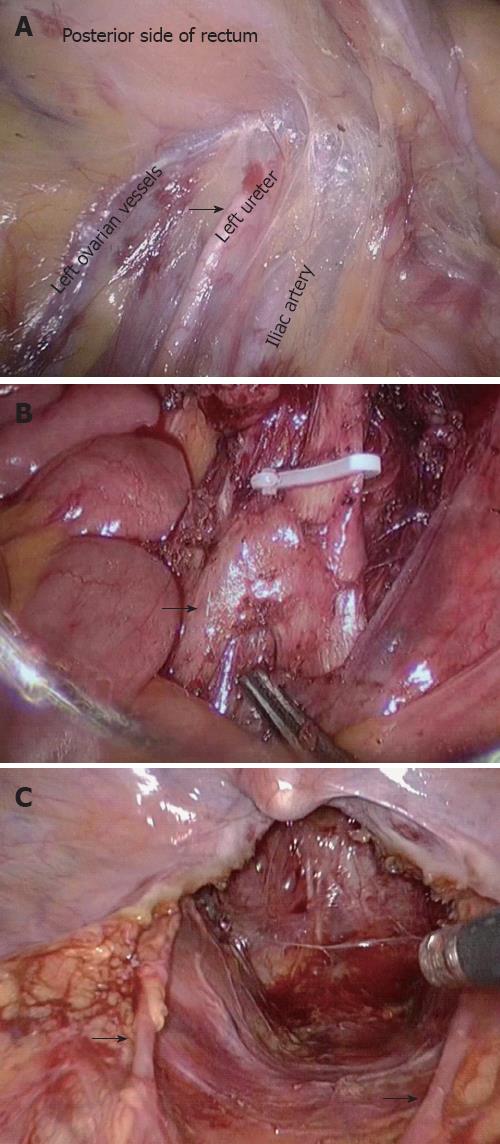

Firstly, the peritoneal cavity was inspected carefully for any metastasis or tumor implantation. Adopting a median-to-lateral approach, the sigmoid was held by the assistant to the left and the right mesorectum was dissected starting from the sacral promontory. Sharp dissection continued along the “yellow-white boundary”, that is, between the adipose tissue in the sigmoid colon mesorectum and left peritoneum to the junction of the mesorectum. Dissection then proceeded as far as the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). Care was taken not to injure the left ureter while dissecting the IMA (Figure 1A). The IMA and its concomitant vein were skeletonized and ligated using endoscopic clips close to the origin of the IMA. The left colic artery and vein were preserved (Figure 1B). It should be noted that the superior hypogastric plexus and sympathetic hypogastric nerves were at risk at this level (Figure 1C).

The next phase of surgery was pelvic dissection. The peritoneum was incised from the level of the sacral promontory posterior to the rectum down to the apex of the coccyx. It was important to recognize the loose avascular plane between the parietal and visceral pelvic fascia before initiating sharp dissection of the presacral area. Anterior dissection occurred in the retrovesical septum in males and in the retrovaginal space in females. The rectosacral ligament and anococcygeal ligament were divided and incised at the level of the fourth sacral vertebra. The mesorectum was circumferentially mobilized while kept intact. A linear endoscopic cutting stapler was introduced to transect the rectum 2-5 cm below the tumor. Depending on the size of the lesion, a transverse incision of 3-4 cm was made to extract the specimen through a wound protector. The distal colon was transected 10 cm above the lesion. Before re-establishing the pneumoperitoneum, an anvil of the circular stapler was placed in the proximal colon and was fixed by a purse-string suture. The bowel was then returned to the peritoneal cavity, and the incision was sutured. The pneumoperitoneum was re-established. The last step of the procedure was to perform a low or ultra low rectal anastomosis with a circular stapler inserted transanally. The two tissue donuts created by the circular stapler were verified for integrity. The distal donut was sent for pathological examination as the circumferential margin.

For patients who have a deep, narrow pelvis, laparoscopic rectal transection is difficult. To guarantee a microscopically clear distal margin, the rectum was transected under direct vision with an assistant pulling the rectum outwards via the anus. Preservation of the sphincters was pursued based on the ability to achieve radical tumor removal. In patients with a very low tumor, the sphincters were unable to be preserved. The specimen was removed from the perineal incision and a permanent colostomy was performed at the anterolateral port.

Conversion was defined as performing any procedure using an open technique, other than extracting the specimen or transection of rectal cancer via the anus. The decision to convert was made when major complications occurred or when radical removal was impossible.

Patients in the OTME group underwent routine operation according to the TME principles. All patients were stratified based on tumor-node-metastasis classification. The duration of postoperative analgesia was as needed and was monitored. According to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, patients who could possibly benefit received adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Shanghai Cancer Center, Fudan University and all patients gave informed consent.

The statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS software package version 13.0 (Chicago, IL, United States) and Windows 7. Parametric variables were expressed as mean ± SD. The Student’s t test was used to assess differences between the LTME and OTME groups. The χ2 test (or Fisher’s exact test where appropriate) and exact tests were performed to compare variables between the two groups. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Between September 2008 and July 2011, a total of 138 patients were randomly assigned to either the LTME group or the OTME group. Sixty-seven patients underwent LTME and 71 patients underwent OTME. The sex ratio (male: female) was 1.3:1 and 1.29:1 for LTME and OTME, respectively. The mean age was 58.4 ± 13.6 years in the LTME group, and 59.6 ± 9.4 years in the OTME group. The two groups were well matched for age, sex ratio, body mass index, ASA, pathological tumor staging and differentiation grades as shown in Table 1.

| LTME | OTME | P value | |

| (n = 67) | (n = 71) | ||

| Characteristics | |||

| Age (yr) | 58.4 ± 13.6 | 59.6 ± 9.4 | 0.910 |

| Sex ratio (male:female) | 1.3:1 | 1.29:1 | 0.918 |

| BMI | 23.6 ± 2.6 | 23.4 ± 1.8 | 0.886 |

| ASA | 0.846 | ||

| I | 57 | 63 | |

| II | 9 | 7 | |

| III | 1 | 1 | |

| pTNM classification | 0.892 | ||

| I | 7 | 9 | |

| II | 46 | 49 | |

| III | 14 | 13 | |

| Differentiation grades | 0.964 | ||

| Well-moderately differntiated | 63 | 65 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 4 | 6 | |

| Distal margin (cm) | 3.6 ± 1.9 | 3.3 ± 1.7 | 0.648 |

| Comparisons | |||

| Sphincter-preserving surgery (%) | 44 (65.7) | 43 (60.6) | 0.046 |

| Operating time (min) | 216.4 ± 68.3 | 162.7 ± 42.5 | 0.032 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 86.9 ± 37.6 | 119.1 ± 32.7 | 0.018 |

| Postoperative analgesia (d) | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 1.8 | 0.008 |

| Duration of urinary drainage (d) | 4.7 ± 1.8 | 6.9 ± 3.4 | 0.016 |

| Time to pass flatus (h) | 46.9 ± 14.8 | 95.6 ± 54.8 | 0.004 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 10.4 ± 4.3 | 13.8 ± 5.9 | 0.036 |

| Length of specimen (cm) | 18.4 ± 4.2 | 19.7 ± 6.1 | 0.786 |

| Number of lymph nodes harvested | 20.3 ± 8.3 | 21.1 ± 6.7 | 0.924 |

| Positive circumferential margin (%) | 1.5 | 2.8 | 0.068 |

As shown in Table 1, there was no statistical difference in the types of surgical procedures chosen, including LAR and APR. The resection was considered curative in all cases. The sphincter-preserving rate was 65.7% (44/67) for LTME and 60.6% (43/71) for OTME and the difference was statistically significant. No protective diverting stoma was fashioned in either groups. Conversion to an open procedure was required in 2 cases (2.99%) due to ureter damage and severe adhesion, respectively.

Despite the fact that the operating time was significantly longer for LTME than OTME, there was significantly less hemorrhage in the LTME group than in the OTME group. Patients in the LTME group also enjoyed a significantly faster postoperative recovery, including lower requirement for analgesia and urinary drainage, faster return of bowel movement and earlier hospital discharge.

One patient (1.5%) suffered an anastomotic leakage in both the LTME group and in the OTME group (1.4%). A total of 4 patients suffered an obstruction, 1 (1.5%) in the LTME group and 3 (4.2%) in the OTME group. In addition, 1 patient and 2 patients in the LTME group and OTME group, respectively, suffered a wound infection. These differences were not statistically significant. There was no perioperative mortality (Table 2).

| Complications | LTME | OTME |

| Ureter damage | 1 | 0 |

| Anastomotic leak | 1 | 1 |

| Obstruction | 1 | 3 |

| Wound infection | 1 | 2 |

With regard to oncological adequacy, the length of the specimen, distal margin of the tumor, number of harvested lymph nodes and positive circumferential margin were all comparable between the two groups. Short-term follow-up was available for all patients, with a median follow-up period of 21 mo (range: 9-56 mo). No port site recurrence, anastomotic recurrence or mortality was observed during the follow-up period.

Although laparoscopic surgery for colon cancer has been widely accepted due to its proven benefits, this technique for rectal cancer is controversial. In this report, we compared laparoscopic surgery to open surgery following TME principles in a consecutive series of patients who were operated on by a team of surgeons extensively experienced in laparoscopic colorectal surgery.

There is a growing body of literature reporting similar outcomes following LTME and OTME. Our results did not differ from the conclusion drawn from other publications that LTME was safe and feasible. Patients who underwent LTME benefited from a faster recovery, including less bleeding, less pain, faster return of urinary function and bowel movement, similar to that found in previous studies[11].

However, there is still debate on whether LTME can deliver an equally satisfying oncological radicality, allowing tumor-free margin and sufficient lymph node yield, while being minimally invasive[12]. There is a lack of multicenter randomized trials addressing this particular issue. While we are still waiting for the results of the COLOR II trials, CLASICC remains the only randomized controlled trial available[13,14]. The early results of CLASICC reported higher, but non-significant, rates of positive circumferential resection margin involvement, which did not translate into a difference in 3-year local recurrence rates. The 5-year follow-up results of the CLASICC trial were unable to show a difference in local recurrence, suggesting that this was probably the result of a learning curve effect. Not surprisingly, most investigations have reported different results. According to a meta-analysis conducted by Anderson et al[15], the positive radical margin involvement rate of rectal cancer was not significantly different between laparoscopic surgery and open surgery. Similar results were obtained for distal margin involvement.

With regard to lymph node yield, our study reported a mean number of 20.3 lymph nodes for LTME and 21.1 for OTME with no statistical difference. This was slightly less than that found be Dulucq et al[16]. They retrieved an average of 24.5 lymph nodes. However, our results were superior to most other studies where the mean number of lymph nodes harvested varied from 8 to 14[17].

Due to the complicated nature of the TME procedure for middle and low rectal cancer, there are only a few publications which compare sphincter-preserving rates between laparoscopic and open approaches. It is worth noting that in our series, the sphincter-preserving rate was significantly higher in the LTME group. This may have been due to the fact that LTME provides the surgeon with a much more flexible operating space and allows them to dissect more easily down to the pelvic floor especially in patients with a deep, narrow pelvis. This clear, magnified and direct view is not available during OTME[18,19]. Nonetheless, this study showed that having a deep, narrow pelvis with a large tumor complicated the LTME procedure and prolonged the operating time, but did not affect postoperative outcomes[20]. The introduction of a linear endoscopic cutting stapler also guarantees a more satisfactory distal transection. Even when sphincter resection was inevitable, these advantages still facilitated pelvic surgery. Similar results were reported by Gezen et al[21] who had a higher rate of neoadjuvant chemoradiation-treated patients in the LTME group. However, these advantages were not found in the largest series of rectal laparoscopic surgery, involving 612 patients, led by Zheng et al[22]. It is noteworthy that an increased rate of APR was observed in the LTME group in a relatively small series of Greek patients with mid and rectal cancer. This might be explained by the significantly lower location of the tumors in the LTME patients[23].

Another advantage of laparoscopic surgery is greater magnification and better illumination of the surgical field, thus allowing better exposure of the autonomic nerves and their protection. Our study showed that patients in the LTME group required a significantly shorter period of urinary drainage. Considering the mean age in this series, patients were predisposed to possible sexual dysfunction before surgery. However, the incidence of postoperative sexual dysfunction was not taken into account in this study.

Conversion has always been a major concern of laparoscopic rectal surgery. Studies in the early 2000s n reported a conversion rate as high as 20%. The CLASICC study also associated conversion with a clear survival disadvantage. However, researchers in the CLASICC trial were unable to attribute this disadvantage to advanced tumor stage or to surgeon-related factors. Conversion was found to be associated with poor prognosis[24]. The latest studies report a conversion rate of 3%-22%, suggesting the involvement of patient selection and surgeons. In the present study, our conversion rate was 2.99%, and was closer to that found by Leroy et al[25] and Milsom et al[26]. This may be explained by the exclusion of patients staged at cT3/4 cTxN+ or with a former history of pelvic radiotherapy. With regard to postoperative complications, the distribution and incidence was similar between the 2 groups. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis led by Lin et al[27] concluded that robotic surgery was superior to laparoscopic surgery in terms of conversion, and could be an alternative in patients who are more likely to undergo conversion.

Admittedly, a clear limitation of our study was that selection bias cannot be completely, even though the two groups were well balanced in terms of demographics and tumor statistics. However, by prospectively enrolling a consecutive series of patients operated on by the same team of surgeons, we hoped to avoid the learning curve effect. The follow-up period was too short to draw any conclusions as to the long-term outcome of LTME versus OTME, however, by continuing to enroll and follow-up patients, we hope to deliver more valuable information in the future.

Our study demonstrated that laparoscopic TME is safe and feasible, with an oncological adequacy comparable to the open approach. From our perspective, laparoscopic TME is performed through laparoscopic apparatus which are thin and long. In this way, tumors can be completely removed almost without being touched. Further studies with more patients and longer follow-up are needed to confirm the present results.

Rectal cancer accounts for approximately half of all colorectal cancer cases in China. With the introduction of total mesorectal excision (TME), laparoscopic technique, as well as pre- and postoperative chemo-radiotherapy, the local control rate and survival in rectal cancer patients have been dramatically improved.

Although laparoscopy in colon cancer has gained acceptance due to its proven benefits, laparoscopy in rectal cancer is still not recommended as the treatment of choice by National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines. In this study, the authors demonstrated that laparoscopic TME (LTME) was advantageous in terms of clinical outcomes and comparable in oncological outcomes to open TME (OTME) in patients with mid and low rectal cancers.

Recent reports have highlighted similar outcomes following LTME and OTME in rectal cancer patients. This is the first study to prospectively compare LTME and OTME in a consecutive series of patients with middle and low rectal cancer regardless of the preservation of sphincters.

The present analysis confirmed the short-term benefits and comparable oncological adequacy of laparoscopic TME compared with the open procedure. This will be comforting to those surgeons performing the technique and should help to promote the laparoscopic TME approach so that a large multicenter randomized trial of LTME can be conducted to demonstrate its long-term benefits.

The manuscript is generally well written, has an academic highlight that of the first study to prospectively compare LTME and OTME in a consecutive series of patients with middle and low rectal cancer. It is important that the shape and location of the intersigmoid recess for providing surgery of anus and rectum in laparoscopic total mesorectal excision and open mesorectal excision.

Peer reviewer: Li YS, Reprint Author, Tianjin Med Univ, Department Anat and Neurobiol, QiXingTai Rd 22, Tianjin 300070, China

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Heald RJ, Husband EM, Ryall RD. The mesorectum in rectal cancer surgery--the clue to pelvic recurrence? Br J Surg. 1982;69:613-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1985] [Cited by in RCA: 1937] [Article Influence: 45.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Bach SP, Hill J, Monson JR, Simson JN, Lane L, Merrie A, Warren B, Mortensen NJ. A predictive model for local recurrence after transanal endoscopic microsurgery for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96:280-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hazebroek EJ. COLOR: a randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic and open resection for colon cancer. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:949-953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fleshman J, Sargent DJ, Green E, Anvari M, Stryker SJ, Beart RW, Hellinger M, Flanagan R, Peters W, Nelson H. Laparoscopic colectomy for cancer is not inferior to open surgery based on 5-year data from the COST Study Group trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246:655-662; discussion 662-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 789] [Cited by in RCA: 802] [Article Influence: 44.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Day A, Smith R, Jourdan I, Rockall T. Laparoscopic TME for rectal cancer: a case series. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2012;22:e98-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lujan J, Valero G, Biondo S, Espin E, Parrilla P, Ortiz H. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer: results of a prospective multicentre analysis of 4,970 patients. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:295-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Quarati R, Summa M, Priora F, Maglione V, Ravazzoni F, Lenti LM, Marino G, Grosso F, Spinoglio G. A Single Centre Retrospective Evaluation of Laparoscopic Rectal Resection with TME for Rectal Cancer: 5-Year Cancer-Specific Survival. Int J Surg Oncol. 2011;2011:473614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cheung HY, Ng KH, Leung AL, Chung CC, Yau KK, Li MK. Laparoscopic sphincter-preserving total mesorectal excision: 10-year report. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:627-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jayne DG, Thorpe HC, Copeland J, Quirke P, Brown JM, Guillou PJ. Five-year follow-up of the Medical Research Council CLASICC trial of laparoscopically assisted versus open surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1638-1645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 830] [Cited by in RCA: 737] [Article Influence: 49.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Leung KL, Kwok SP, Lam SC, Lee JF, Yiu RY, Ng SS, Lai PB, Lau WY. Laparoscopic resection of rectosigmoid carcinoma: prospective randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1187-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 707] [Cited by in RCA: 656] [Article Influence: 31.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Khaikin M, Bashankaev B, Person B, Cera S, Sands D, Weiss E, Nogueras J, Vernava A, Wexner SD. Laparoscopic versus open proctectomy for rectal cancer: patients' outcome and oncologic adequacy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:118-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kuhry E, Schwenk WF, Gaupset R, Romild U, Bonjer HJ. Long-term results of laparoscopic colorectal cancer resection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;CD003432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Buunen M, Bonjer HJ, Hop WC, Haglind E, Kurlberg G, Rosenberg J, Lacy AM, Cuesta MA, D'Hoore A, Fürst A. COLOR II. A randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic and open surgery for rectal cancer. Dan Med Bull. 2009;56:89-91. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Tan KY, Konishi F. Long-term results of laparoscopic colorectal cancer resection: current knowledge and what remains unclear. Surg Today. 2010;40:97-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Anderson C, Uman G, Pigazzi A. Oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:1135-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dulucq JL, Wintringer P, Stabilini C, Mahajna A. Laparoscopic rectal resection with anal sphincter preservation for rectal cancer: long-term outcome. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1468-1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rosin D, Lebedyev A, Urban D, Aderka D, Zmora O, Khaikin M, Hoffman A, Shabtai M, Ayalon A. Laparoscopic resection of rectal cancer. Isr Med Assoc J. 2011;13:459-462. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Poon JT, Law WL. Laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer: a review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3038-3047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Champagne BJ, Makhija R. Minimally invasive surgery for rectal cancer: are we there yet? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:862-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim JY, Kim YW, Kim NK, Hur H, Lee K, Min BS, Cho HJ. Pelvic anatomy as a factor in laparoscopic rectal surgery: a prospective study. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2011;21:334-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gezen C, Altuntas YE, Kement M, Aksakal N, Okkabaz N, Vural S, Oncel M. Laparoscopic and conventional resections for low rectal cancers: a retrospective analysis on perioperative outcomes, sphincter preservation, and oncological results. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22:625-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zheng MH, Feng B, Hu CY, Lu AG, Wang ML, Li JW, Hu WG, Zang L, Mao ZH, Dong TT. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for middle and low rectal cancer. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2010;19:329-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gouvas N, Tsiaoussis J, Pechlivanides G, Zervakis N, Tzortzinis A, Avgerinos C, Dervenis C, Xynos E. Laparoscopic or open surgery for the cancer of the middle and lower rectum short-term outcomes of a comparative non-randomised study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:761-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ströhlein MA, Grützner KU, Jauch KW, Heiss MM. Comparison of laparoscopic vs. open access surgery in patients with rectal cancer: a prospective analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:385-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Leroy J, Jamali F, Forbes L, Smith M, Rubino F, Mutter D, Marescaux J. Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision (TME) for rectal cancer surgery: long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:281-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Milsom JW, de Oliveira O, Trencheva KI, Pandey S, Lee SW, Sonoda T. Long-term outcomes of patients undergoing curative laparoscopic surgery for mid and low rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1215-1222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lin S, Jiang HG, Chen ZH, Zhou SY, Liu XS, Yu JR. Meta-analysis of robotic and laparoscopic surgery for treatment of rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:5214-5220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |