Published online Dec 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i47.6943

Revised: October 22, 2012

Accepted: October 30, 2012

Published online: December 21, 2012

AIM: To evaluate the treatment outcomes of clevudine compared with entecavir in antiviral-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB).

METHODS: We retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of CHB patients treated with clevudine 30 mg/d and compared their clinical outcomes with patients treated with entecavir 0.5 mg/d. The biochemical response, as assessed by serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity, virologic response, as assessed by serum hepatitis B virus DNA (HBV DNA) titer, serologic response, as assessed by hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) status, and virologic breakthrough with genotypic mutations were assessed.

RESULTS: Two-hundred and fifty-four patients [clevudine (n = 118) vs entecavir (n = 136)] were enrolled. In clevudine-treated patients, the cumulative rates of serum ALT normalization were 83.9% at week 48 and 91.5% at week 96 (80.9% and 91.2% in the entecavir group, respectively), the mean titer changes in serum HBV DNA were -6.03 and -6.55 log10 copies/mL (-6.35 and -6.86 log10 copies/mL, respectively, in the entecavir group), and the cumulative non-detection rates of serum HBV DNA were 72.6% and 83.1% (74.4% and 83.8%, respectively, in the entecavir group). These results were similar to those of entecavir-treated patients. The cumulative rates of HBeAg seroconversion were 21.8% at week 48 and 25.0% at week 96 in patients treated with clevudine, which was similar to patients treated with entecavir (22.8% and 27.7%, respectively). The virologic breakthrough in the clevudine group occurred in 9 (7.6%) patients at weeks 48 and 15 (12.7%) patients at week 96, which primarily corresponded to genotypic mutations of rtM204I and/or rtL180M. There was no virologic breakthrough in the entecavir group.

CONCLUSION: In antiviral-naive CHB patients, long-term treatment outcomes of clevudine were not inferior to those of entecavir, except for virologic breakthrough.

- Citation: Kim SB, Song IH, Kim YM, Noh R, Kang HY, Lee HI, Yang HY, Kim AN, Chae HB, Lee SH, Kim HS, Lee TH, Kang YW, Lee ES, Kim SH, Lee BS, Lee HY. Long-term treatment outcomes of clevudine in antiviral-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(47): 6943-6950

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i47/6943.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i47.6943

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a serious health problem worldwide and a major risk factor for the development of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), two grave complications that have a high morbidity and mortality[1,2]. Although the seroprevalence rate of HBV in the South Korean population has gradually decreased since the development of the HBV vaccine in the 1980s, the rate is still high compared to Western countries[3,4].

Since the first oral antiviral agent against HBV, lamivudine, was introduced in 1997[5-7], there has been a significant evolution in antiviral fields for patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB).

Among HBV-targeted oral agents available in Korea, such as lamivudine, adefovir, clevudine, entecavir, and telbivudine, clevudine (CLV) and entecavir (ETV) are now prescribed to a large extent, and they were approved by the South Korean Food and Drug Administration in 2006 and subsequently marketed in Korea as a 1st-line treatment for patients with chronic HBV infection. CLV, which was developed in Korea, is a pyrimidine nucleoside analog with potent antiviral activity against HBV[8]. CLV therapy for 24 wk showed durable off-treatment virologic suppression and excellent on-treatment virologic response in both hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive CHB patients and HBeAg-negative CHB patients[9,10]. However, CLV-related myopathy was found in a previous global clinical trial, which was controlled due to unfavorable safety profiles despite a tolerable, manageable, and self-limited level of adverse effects.

In contrast, after the clinical establishment of ETV, an analog of the deoxyguanosine nucleoside, as an antiviral agent against HBV, ETV has become the most frequently prescribed drug in clinical fields for the treatment of CHB patients both globally and in Korea, with advantages of potent HBV suppression and low genotypic resistance[11-13].

This study was performed to evaluate the long-term treatment efficacy and safety of CLV in antiviral-naive patients with chronic HBV infection on the basis of those of ETV as a comparative standard of the present study.

The study subjects were CHB patients who were treated with CLV or ETV as a 1st-line treatment at six University Hospitals in Daejeon and Chungcheong provinces in Korea between January 2007 and March 2010. CHB was diagnosed either histologically or clinically. The clinical diagnosis of CHB was determined through the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen over at least a 6-mo period, a high titer of serum HBV DNA, and sustained or fluctuating elevations of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity at the corresponding times. In this study, we enrolled CHB patients with a serum ALT value ≥ 80 IU/L and serum HBV DNA titer > 100 000 copies/mL who had been taking CLV 30 mg or ETV 0.5 mg daily. We followed the global guideline for ALT value, which is 2 times over the normal value. Patients with the following criteria were excluded: age less than 18 years; interferon therapy within 6 mo; HCC diagnosis prior to entrance to this study; alcohol consumption more than 80 g per week; elevated serum ALT value due to other causes, such as drugs, toxins, autoimmune-related or metabolic-related liver diseases, co-infection with hepatitis C virus or human immunodeficiency virus; creatinine clearance less than 50 mL/min; or severe systemic illnesses. During the treatment with antiviral agents, drug compliance was recorded, and patients who did not take the antiviral drug for more than 12 wk were also excluded from the study. The selection of antiviral drug was determined by the patients after they were provided with information on the drugs and their relative merits. The study was conducted in accordance and compliance with ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

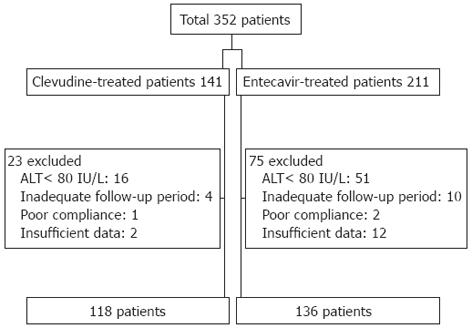

Among the 352 total CHB patients treated with CLV or ETV, we analyzed the clinical data of 254 patients in this study after excluding 67 patients with serum ALT value < 80 IU/L and 31 patients with inadequate follow-up, poor compliance, or insufficient data (Figure 1).

Clinical baseline characteristics, such as age, gender, history of alcohol consumption, presence of cirrhosis, history of prior antiviral therapy, and other medical history, were retrospectively reviewed and analyzed. Cirrhosis was diagnosed based on histologic evidence through liver biopsy or clinical manifestations of portal hypertension, such as gastroesophageal varices or other collaterals, ascites, encephalopathy, splenomegaly, thrombocytopenia, and radiologic features suggestive of cirrhosis on liver ultrasound or computed tomography.

Serum ALT, creatinine, HBeAg/anti-HBe, and HBV DNA titer were recorded approximately 3-mo interval following CLV or ETV administration, and if the examination times were missed, the latest results within a month were used for analysis.

Serum HBV DNA titers were determined by real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with two types of detection indicators: one model with a minimum detection level of 316 copies/mL (Cobas Amplicor PCR, Roche Molecular Systems, United States) and the other model with a minimum detection level of 70 copies/mL (Cobas Taqman, Roche Diagnostics, United States). Mutant analysis of HBV DNA for detecting genotypic resistance was performed by polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism or direct sequencing in patients showing virologic breakthrough.

We evaluated the biochemical responses, including the median change and cumulative normalization rate of the serum ALT value, the virologic responses, including the decrement degree and cumulative non-detection rate of the serum HBV DNA titer, the serologic responses, including the cumulative rates of HBeAg clearance and HBeAg seroconversion, and the antiviral resistance, including the cumulative rate of virologic breakthrough with genotypic mutation.

Non-detection of HBV DNA was defined as a serum HBV DNA titer less than 316 copies/mL. ALT normalization was defined as a serum ALT value less than 40 IU/L. HBeAg clearance was defined as a loss of HBeAg in a patient who was previously positive for HBeAg, and HBeAg seroconversion was defined as a loss of HBeAg and an acquisition of anti-HBe in a patient who was previously positive for HBeAg and negative for anti-HBe. Virologic breakthrough was defined as an increase in serum HBV DNA titer by > 1 log10 (10-fold) above nadir after achieving a virologic response during continued treatment. Genotypic resistance was defined as the detection of mutations that have been shown in vitro to confer resistance to an antiviral agent. In this study, rtM204V/I and rtL180M were considered CLV-related mutations due to common profiles of genotypic mutation for CLV and lamivudine[14,15]. We also defined no virologic response as a decrease < 2 log10 copies/mL in serum HBV DNA titer after 24 wk of drug administration.

When the patients experienced constitutional symptoms, such as weakness, fatigue, or muscle pain, during the administration of antiviral agents, the serum creatinine phosphokinase (CK) activity was measured for the detection of clinical myopathy. Clinical myopathy was defined as a presence of the above-mentioned symptoms with a simultaneous elevation of serum CK activity.

SPSS software (Windows version 15.0, Chicago, IL, United States) was used for statistical analysis for comparison. Student’s t-test was applied for consecutive variables, and the χ2 test or Fisher’s verification was applied for categorical variables. Statistical significance was determined when the P-value was < 0.05.

Of the 254 patients with CHB enrolled in this study, 118 patients (70 men and 48 women) were treated with CLV, and 136 patients (86 men and 50 women) were treated with ETV (Figure 1). The mean age of the patients was 42 ± 11 years. None of the patients were previously treated with any antiviral drugs including interferon. No significant difference was noted in the number of patients with cirrhosis (12.7% in the CLV group vs 22.1% in the ETV group, P = 0.052), HBeAg positivity (74.6% in the CLV group vs 69.1% in the ETV group, P = 0.322), median serum ALT value [158 (107-263) IU/L in the CLV group vs 139.5 (101.5-288.5) IU/L in the ETV group, P = 0.206], and serum HBV DNA titer (7.3 ± 1.1 log10 copies/mL in the CLV group vs 7.4 ± 1.1 log10 copies/mL in the ETV group, P = 0.556) between the CLV and ETV groups. The median follow-up period was similar in the two groups (74 ± 24 wk in the CLV group and 75 ± 21 wk in the ETV group, P = 0.922) (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Clevudine(n = 118) | Entecavir(n = 136) | P-value |

| Age1, yr | 42 ± 11 | 41 ± 11 | 0.358 |

| Male gender | 70 (59.3) | 86 (63.2) | 0.528 |

| Cirrhosis | 15 (12.7) | 30 (22.1) | 0.052 |

| ALT2, IU/L | 158 (107-263) | 139.5 (101.5-288.5) | 0.206 |

| HBeAg-positive | 88 (74.6) | 94 (69.1) | 0.322 |

| HBV DNA level3, log10 copies/mL | 7.3 ± 1.1 | 7.4 ± 1.1 | 0.556 |

| Follow-up period3, wk | 74 ± 24 | 75 ± 21 | 0.922 |

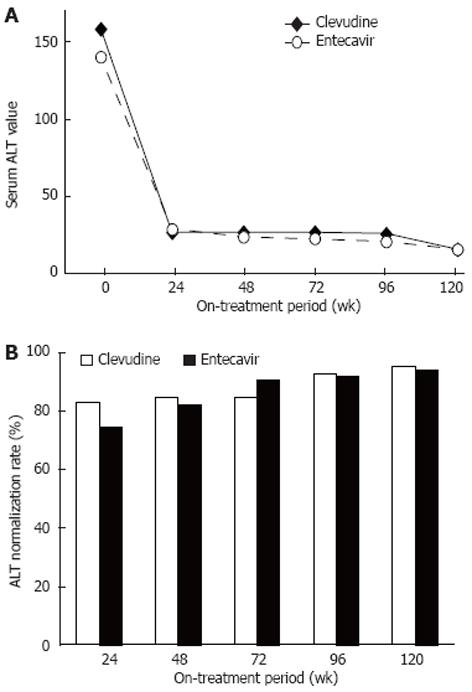

The median values of serum ALT at weeks 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 after treatment were 27, 27, 27, 26, and 16 IU/L in the CLV group and 29, 24, 23, 21, and 16 IU/L in the ETV group, respectively (Figure 2A). The cumulative rates of serum ALT normalization at the same points of time were 81.9% (95/116), 83.9% (99/118), 83.9% (99/118), 91.5% (108/118), and 94.1% (111/118) in the CLV group and 73.9% (99/134), 80.9% (110/136), 89.7% (122/136), 91.2% (124/136), and 92.6% (126/136) in the ETV group, respectively (Figure 2B). No significant difference was noted in either the median value or cumulative normalization rate of serum ALT between the two groups.

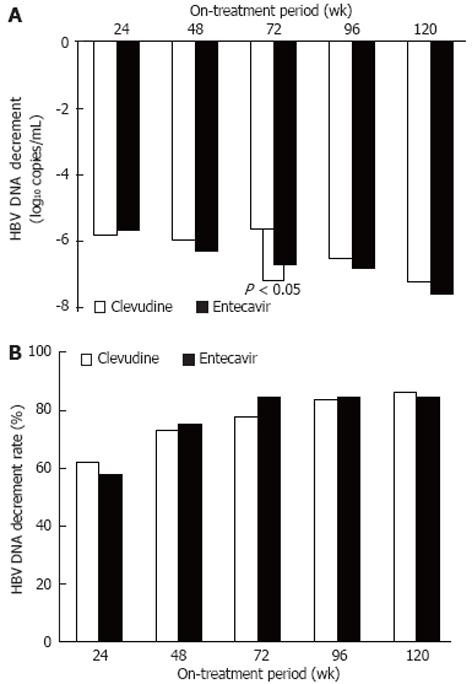

The titer decrements of serum HBV DNA were -5.83, -6.03, -5.66, -6.55, and -7.28 log10 copies/mL in the CLV group and -5.70, -6.35, -6.74, -6.86, and -7.63 log10 copies/mL in the ETV group at weeks 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 after treatment, respectively. There was no significant difference between the groups, except for serum HBV DNA titer at week 72 (CLV group vs ETV group, P < 0.05)(Figure 3A). At the same time points, the cumulative non-detection rates of serum HBV DNA were 61.3% (68/111), 72.6% (85/117), 77.1% (91/118), 83.1% (98/118), and 85.6% (101/118) in the CLV group and 57.3% (71/124), 74.4% (99/133), 83.8% (114/136), 83.8% (114/136), and 83.8% (114/136) in the ETV group, respectively, showing no significant difference (Figure 3B).

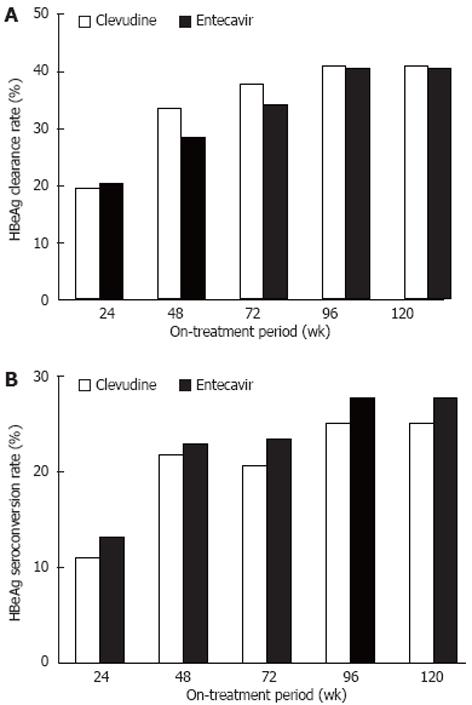

In patients who were positive for HBeAg, the cumulative rate of HBeAg clearance was 19.5% (16/82), 33.3% (29/87), 37.5% (33/88), 40.9% (36/88), and 40.9% (36/88) in the CLV group and 20.2% (17/84), 28.3% (26/92), 34.0% (32/94), 40.4% (38/94), and 40.4% (38/94) in the ETV group at weeks 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 after drug administration, respectively (Figure 4A). The cumulative rate of HBeAg seroconversion was 11.0% (9/82), 21.8% (19/87), 20.5% (18/88), 25.0% (22/88), and 25.0% (22/88) in the CLV group and 13.1% (11/84), 22.8% (21/92), 23.4% (22/94), 27.7% (26/94), and 27.7% (26/94) in the ETV group, respectively, at the same time points (Figure 4B). No significant difference was observed in the cumulative rates of HBeAg clearance or HBeAg seroconversion between the two groups.

Virologic breakthrough in the CLV group occurred in 7.6% (9/118) of the patients at 1-year after administration and 12.7% (15/118) of the patients at 2-years after administration, while no virologic breakthrough occurred in the ETV group throughout the treatment period (CLV group vs ETV group, P < 0.05). Most of the patients with virologic breakthrough showed a genotypic mutation at sites rt204 and rt180, either singly or combined, except for two patients, who showed mutation at site rt80. Only two patients (1.7%) in the CLV group experienced clinical myopathy, and they showed self-limited recovery with conservative management without dose reduction or discontinuation of CLV.

1-(2-deoxy-2-fluoro-β-L-arabinofuranosyl)thymine (CLV) is a nucleoside analogue with powerful antiviral activity against HBV; it inhibits DNA polymerase through the binding of clevudine-triphosphate to the polymerase[16]. CLV is one of the currently available antiviral agents used as a 1st-line treatment for CHB patients in Korea, an HBV-endemic area. Although CLV was reported to be beneficial in virologic suppression on-treatment and off-treatment in CHB patients, these results were reported in a few clinical studies with small study populations and/or short follow-up periods[9,10,17,18], and a large-scale, long-term comparative study should have been required for verifying the efficacy of CLV. With these considerations, the present study was conducted to assess relatively long-term (median follow-up period of 74 wk) clinical outcomes of CLV in antiviral-naive CHB patients compared with ETV-treated patients during the same period, and this study was conducted in multiple regional institutes.

ETV is strongly recommended as a 1st-line treatment agent in the AASLD and EASL guidelines[19,20], because it effectively suppresses HBV DNA and has a low genotypic resistance. Because of the globally established effects of ETV on HBV infection, the present study used clinical outcomes of ETV as a comparative standard for estimating the treatment efficacy of CLV in patients with CHB.

In this study, the cumulative rate of serum ALT normalization in CLV-treated patients increased from 83.9% at week 48 to 91.5% at week 96, which was similar to ETV-treated patients. Previous studies have reported that CLV showed a wide-range of ALT normalization (68.2% to 98.1% at week 24 and 77.3% to 87.5% at week 48)[9,10,17,21-23]. The cumulative non-detection rate of serum HBV DNA in the CLV group also increased from 61.3% at week 24 to 72.6% at week 48 and 83.1% at week 96, which was similar to the ETV group. These rates seem to be slightly lower than previously reported HBV DNA non-detection rates[17,21,24,25], most likely resulting from the use of a stricter detection assay of HBV DNA in our study. HBV DNA detection is mainly affected by the detection limit of the quantitation tool of HBV DNA. The real-time polymerase chain reaction method used in our study institutes is the most sensitive method for the quantitation of serum HBV DNA, and the lower limit of detection was 70 copies/mL.

CLV-treated patients showed excellent biochemical and virological responses during treatment and these response were not inferior to the responses shown in ETV-treated patients. Specifically, the titer decrement of serum HBV DNA was rapid and potent, as it was nearly at the 90% level of decrement at 96 wk after treatment for 24 wk. The rapid and potent suppression of HBV DNA is generally a significant indicator for maintaining an on-treatment virological response and sustained off-treatment virological response[26].

This study revealed that the HBeAg clearance rate in the CLV group increased from 33.3% at week 48 to 40.9% at week 96, and this pattern was similar to the ETV group and the results of previous CLV-related studies (11.1%-25.7% at 6 mo and 23.5%-48.0% at 12 mo)[9,10,21,24]. The HBeAg seroconversion rate of CLV-treated patients, which was 21.8% at week 48 and 25.0% at week 96, was in agreement with ETV-treated patients and comparable to results from previous studies (7.6%-21.4% at 6 mo and 11.8%-16.9% at 12 mo)[9,10,18,25]. Our study did not show a significant difference either HBeAg clearance or HBeAg seroconversion rates between the two groups treated with CLV or ETV.

In CLV-treated patients, the cumulative rate of virologic breakthrough increased from 7.6% at week 48 to 12.7% at week 96, while no virologic breakthrough occurred in ETV-treated patients during treatment. Most of the patients with virologic breakthrough had genotypic mutations of rtM204I or rtL180M, as previously reported in other CLV-associated studies. Rt204 of HBV DNA polymerase/reverse transcriptase is the main site relevant to CLV-associated genotypic mutation, with cross-resistance to other antiviral agents, such as lamivudine and telbivudine[14]. The add-on or mono-switch to nucleotide analogs, such as tenofovir or adefovir, is a possible rescue therapy for CLV-resistant CHB patients; however, the choice of drug should be validated through further clinical studies. In addition to rt204, rt80, rt180, rt181, rt184, and rt270 have also been infrequently reported to be mutation sites conferring resistance to CLV. The cumulative rate of virologic breakthrough induced by CLV-associated genotypic mutation has been reported to be 0.7%-14.5% up to 12 mo[18,21,27,28] and 24.4% up to 24 mo[29], which is similar to the results of the present study. Biochemical breakthrough after virologic breakthrough may occur, but several months are required for ALT to increase[30]. We did not compare the interval between biochemical breakthrough and virologic breakthrough because it only occurred in the CLV group. Most of the patients who showed virologic breakthrough were changed to or supplemented with another drug before ALT increased. The current treatment for virologic breakthrough for CLV is similar to that of lamivudine[31].

The biologic mechanism of myopathy related to CLV has not been clearly identified, but mitochondrial dysfunction induced by mtDNA polymerase γ suppression of the phosphorylated CLV metabolite has been hypothesized to be involved[32-34]. Although the incidence rate of myopathy has been reported to be variable (1%-14.6%)[15,17,21,22,25,35], only 1.7% of CLV-treated patients in this study showed clinical myopathy to the tolerable extent of compliance without any modification of drug administration.

The present study has several restrictions. First, this is a retrospective study, which could not entirely escape a non-intentional withdrawal of a number of study candidates prior to study analysis; therefore selection bias was not completely eliminated. This matter could be overcome through a comparative prospective study; Second, the detection limit of the serum HBV DNA titer was different in each institute that participated in this study, which could affect the cumulative non-detection rate of serum HBV DNA, despite the adoption of real-time PCR with a relatively sensitive quantitation indicator; Third, the analysis of clinical myopathy was insufficient because of irregular check-up for obtaining clinical information and data review only through medical records of the patients, which could not exclude the presence of myopathy of a subclinical nature; Fourth, the lack of off-treatment clinical responses suggests that an advanced clinical study sufficient to assess long-term outcomes, such as response maintenance, relapse, and disease progression after treatment, is needed.

In conclusion, we evaluated the clinical outcomes of CLV as a first-line treatment agent in antiviral-naive CHB patients. The on-treatment biochemical, virologic, and serologic responses of CLV, except for genotypic resistance with virologic breakthrough, were as good as and not inferior to the responses of ETV up to a 96-wk period. In the future, clinical data for the rescue therapy of CLV-related antiviral resistance should be mandatory and should be acquired through a large-scale prospective study. A study to determine the conditions under which virologic resistance could be minimized should be performed.

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a serious health problem worldwide and a major risk factor for the development of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, two grave complications that have a high morbidity and mortality. Although the seroprevalence rate of HBV in the South Korean population has gradually decreased since the development of the HBV vaccine in the 1980s, the rate is still high compared to Western countries.

Clevudine (CLV) is one of the currently available antiviral agents used as a 1st-line treatment for chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients in Korea, an HBV-endemic area. Although CLV was reported to be beneficial in virologic suppression on-treatment and off-treatment in CHB patients, these results were reported in a few clinical studies with small study populations and/or short follow-up periods, and a large-scale, long-term comparative study should have been required for verifying the efficacy of CLV.

Authors evaluated the clinical outcomes of CLV as a first-line treatment agent in antiviral-naive CHB patients. The on-treatment biochemical, virologic, and serologic responses of CLV, except for genotypic resistance with virologic breakthrough, were as good as and not inferior to the responses of entecavir up to a 96-wk period. In the future, clinical data for the rescue therapy of CLV-related antiviral resistance should be mandatory and should be acquired through a large-scale prospective study.

The study results suggest that long-term treatment outcomes of clevudine were not inferior to those of entecavir, except for virologic breakthrough in antiviral-naive CHB patients.

Authors reported that long-term treatment outcomes of clevudine in antiviral-naive patients with CHB. This report has the important information. The data is appropriately treated and text is clear although the retrospective study.

Peer reviewers: Tatsuya Ide, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Kurume University School of Medicine, 67 Asahi-machi, Kurume 830-0011, Japan; Guglielmo Borgia, MD, Professor, Public Medicine and Social Security, University of Naples “Federico II”, Malattie Infettive (Ed. 18) Via S Pansini 5, I-80131 Naples, Italy

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Lavanchy D. Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and current and emerging prevention and control measures. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:97-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1734] [Cited by in RCA: 1750] [Article Influence: 83.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Song IH, Kim KS. Current status of liver diseases in Korea: hepatocellular carcinoma. Korean J Hepatol. 2009;15 Suppl 6:S50-S59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim SB, Lee WK, Choi H, Kim SM, Noh R, Kang HY, Lee SS, Ra SS, Gong JH, Shin HD. [A study on viral hepatitis markers and abnormal liver function test in adults living in northwest area of Chungnam]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;53:355-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee DH, Kim JH, Nam JJ, Kim HR, Shin HR. Epidemiological findings of hepatitis B infection based on 1998 National Health and Nutrition Survey in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17:457-462. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Liaw YF, Sung JJ, Chow WC, Farrell G, Lee CZ, Yuen H, Tanwandee T, Tao QM, Shue K, Keene ON, Dixon JS, Gray DF, Sabbat J. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1521-1531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1739] [Cited by in RCA: 1740] [Article Influence: 82.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Matsumoto A, Tanaka E, Rokuhara A, Kiyosawa K, Kumada H, Omata M, Okita K, Hayashi N, Okanoue T, Iino S. Efficacy of lamivudine for preventing hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B: A multicenter retrospective study of 2795 patients. Hepatol Res. 2005;32:173-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lee HJ, Eun R, Jang BI, Kim TN. Prevention by Lamivudine of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients infected with hepatitis B virus. Gut Liver. 2007;1:151-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Asselah T, Lada O, Moucari R, Marcellin P. Clevudine: a promising therapy for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17:1963-1974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yoo BC, Kim JH, Chung YH, Lee KS, Paik SW, Ryu SH, Han BH, Han JY, Byun KS, Cho M. Twenty-four-week clevudine therapy showed potent and sustained antiviral activity in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:1172-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yoo BC, Kim JH, Kim TH, Koh KC, Um SH, Kim YS, Lee KS, Han BH, Chon CY, Han JY. Clevudine is highly efficacious in hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B with durable off-therapy viral suppression. Hepatology. 2007;46:1041-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lampertico P. Entecavir versus lamivudine for HBeAg positive and negative chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2006;45:457-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chang TT, Gish RG, de Man R, Gadano A, Sollano J, Chao YC, Lok AS, Han KH, Goodman Z, Zhu J. A comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1001-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1107] [Cited by in RCA: 1090] [Article Influence: 57.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gish RG, Lok AS, Chang TT, de Man RA, Gadano A, Sollano J, Han KH, Chao YC, Lee SD, Harris M. Entecavir therapy for up to 96 weeks in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1437-1444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 275] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kwon SY, Park YK, Ahn SH, Cho ES, Choe WH, Lee CH, Kim BK, Ko SY, Choi HS, Park ES. Identification and characterization of clevudine-resistant mutants of hepatitis B virus isolated from chronic hepatitis B patients. J Virol. 2010;84:4494-4503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim IH, Lee S, Kim SH, Kim SW, Lee SO, Lee ST, Kim DG, Choi CS, Kim HC. Treatment outcomes of clevudine versus lamivudine at week 48 in naïve patients with HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis B. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:738-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Balakrishna Pai S, Liu SH, Zhu YL, Chu CK, Cheng YC. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus by a novel L-nucleoside, 2'-fluoro-5-methyl-beta-L-arabinofuranosyl uracil. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:380-386. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Kim HJ, Park DI, Park JH, Cho YK, Sohn CI, Jeon WK, Kim BI. Comparison between clevudine and entecavir treatment for antiviral-naïve patients with chronic hepatitis B. Liver Int. 2010;30:834-840. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shin SR, Yoo BC, Choi MS, Lee DH, Song SM, Lee JH, Koh KC, Paik SW. A comparison of 48-week treatment efficacy between clevudine and entecavir in treatment-naïve patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatol Int. 2011;5:664-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2125] [Cited by in RCA: 2171] [Article Influence: 135.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver. [EASL clinical practice guidelines. Management of chronic hepatitis B]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33:539-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1152] [Cited by in RCA: 1155] [Article Influence: 72.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lee HJ, Eun JR, Lee CH, Hwang JS, Suh JI, Kim BS, Jang BK. [Long-term clevudine therapy in nucleos(t)ide-naïve and lamivudine-experienced patients with hepatitis B virus-related chronic liver diseases]. Korean J Hepatol. 2009;15:179-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jang JH, Kim JW, Jeong SH, Myung HJ, Kim HS, Park YS, Lee SH, Hwang JH, Kim N, Lee DH. Clevudine for chronic hepatitis B: antiviral response, predictors of response, and development of myopathy. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:84-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Shim JH, Lee HC, Kim KM, Lim YS, Chung YH, Lee YS, Suh DJ. Efficacy of entecavir in treatment-naïve patients with hepatitis B virus-related decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2010;52:176-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kim MH, Kim KA, Lee JS, Lee HW, Kim HJ, Yun SG, Kim NH, Bae WK, Moon YS. [Efficacy of 48-week clevudine therapy for chronic hepatitis B]. Korean J Hepatol. 2009;15:331-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kim JH, Yim HJ, Jung ES, Jung YK, Kim JH, Seo YS, Yeon JE, Lee HS, Um SH, Byun KS. Virologic and biochemical responses to clevudine in patients with chronic HBV infection-associated cirrhosis: data at week 48. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:287-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Dienstag JL. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1486-1500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 689] [Cited by in RCA: 689] [Article Influence: 40.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ko SY, Kwon SY, Choe WH, Kim BK, Kim KH, Lee CH. Clinical and virological responses to clevudine therapy in chronic hepatitis B patients: results at 1 year of an open-labelled prospective study. Antivir Ther. 2009;14:585-590. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Lee JS, Park ET, Kang SS, Gu ES, Kim JS, Jang DS, Lee KS, Lee JS, Park NH, Bae CH. Clevudine demonstrates potent antiviral activity in naïve chronic hepatitis B patients. Intervirology. 2010;53:83-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yoon EL, Yim HJ, Lee HJ, Lee YS, Kim JH, Jung ES, Kim JH, Seo YS, Yeon JE, Lee HS. Comparison of clevudine and entecavir for treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection: two-year follow-up data. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:893-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kim do Y, Ahn SH, Lee HW, Park JY, Kim SU, Paik YH, Lee KS, Han KH, Chon CY. Clinical course of virologic breakthrough after emergence of YMDD mutations in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. Intervirology. 2008;51:293-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Borgia G, Gentile I. Treating chronic hepatitis B: today and tomorrow. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:2839-2855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Seok JI, Lee DK, Lee CH, Park MS, Kim SY, Kim HS, Jo HY, Lee CH, Kim DS. Long-term therapy with clevudine for chronic hepatitis B can be associated with myopathy characterized by depletion of mitochondrial DNA. Hepatology. 2009;49:2080-2086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kim BK, Oh J, Kwon SY, Choe WH, Ko SY, Rhee KH, Seo TH, Lim SD, Lee CH. Clevudine myopathy in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;51:829-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Tak WY, Park SY, Jung MK, Jeon SW, Cho CM, Kweon YO, Kim SK, Choi YH. Mitochondrial myopathy caused by clevudine therapy in chronic hepatitis B patients. Hepatol Res. 2009;39:944-947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Tak WY, Park SY, Cho CM, Jung MK, Jeon SW, Kweon YO, Park JY, Sohn YK. Clinical, biochemical, and pathological characteristics of clevudine-associated myopathy. J Hepatol. 2010;53:261-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |