Published online Dec 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i45.6645

Revised: September 12, 2012

Accepted: September 19, 2012

Published online: December 7, 2012

AIM: To evaluate the safety of lamivudine (LAM) treatment for chronic hepatitis B in early pregnancy.

METHODS: A total of 92 pregnant women who received LAM treatment either before pregnancy or in early pregnancy were enrolled in this study. All of the pregnant women volunteered to take lamivudine during pregnancy and were not co-infected with hepatitis C virus, human immunodeficiency virus, cytomegalovirus, or other viruses. All infants received passive-active immunoprophylaxis with 200 IU hepatitis B immunoglobulin and three doses of 10 μg hepatitis B vaccines (0-1-6 mo) according to the guidelines for the prevention and treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Adverse events were observed throughout the entire pregnancy and perinatal period, and the effectiveness of lamivudine treatment for blocking mother-to-infant transmission of hepatitis B virus (HBV) was evaluated. All adverse events in mothers and infants during pregnancy and the perinatal period and the HBV mother-to-infant transmission blocking rate were compared with the literature.

RESULTS: Among the 92 pregnant women, spontaneous abortions occurred in 11 cases, while 3 mothers had a second pregnancy after the initial abortion; 72 mothers delivered 73 live infants, of whom 68 infants were followed up for no less than 6 mo, and 12 mothers were still pregnant. During pregnancy, the main maternal adverse events were vaginitis (12/72, 16.7%), spontaneous abortion (11/95, 11.6%), and gestational diabetes (6/72, 8.3%); only one case had 1-2 degree elevation of the creatine kinase level (195 U/L). During the perinatal period, the main maternal adverse events were premature rupture of the membranes (8/72, 11.1%), preterm delivery (5/72, 6.9%), and meconium staining of the amniotic fluid (4/72, 5.6%). In addition, 2 infants were found to have congenital abnormalities; 1 had a scalp hemangioma that did not change in size until 7 mo, and the other had early cerebral palsy, but with rehabilitation training, the infant’s motor functions became totally normal at 2 years of age. The incidence of adverse events among the mothers or abnormalities in the infants was not higher than that of normal mothers or HBV-infected mothers who did not receive lamivudine treatment. In only 2 cases, mother-to-infant transmission blocking failed; the blocking rate was 97.1% (66/68), which was higher than has been previously reported.

CONCLUSION: Lamivudine treatment is safe for chronic HBV-infected pregnant mothers and their fetuses with a gestational age of less than 12 wk or throughout the entire pregnancy.

- Citation: Yi W, Liu M, Cai HD. Safety of lamivudine treatment for chronic hepatitis B in early pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(45): 6645-6650

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i45/6645.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i45.6645

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a global health problem; about two billion people have a past or present HBV infection, of whom 350 million are chronic HBV carriers. Each year, about one million people die of liver failure, cirrhosis, or primary hepatocellular carcinoma, all of which are associated with HBV infection. Lamivudine (LAM) is the first approved oral nucleoside analog (NA) used to treat HBV infection (100 mg/d), and the appearance of LAM marked a new era in the treatment of chronic HBV infection. However, treatment duration is very long, and some patients may become pregnant during that time. Although some studies have previously reported on the safety of LAM treatment for chronic HBV infection in late pregnancy[1-3], there are very few reports about the safety of LAM treatment in early pregnancy[4-6]. The objective of this study was to evaluate the safety of LAM treatment for chronic hepatitis B in early pregnancy or throughout the entire pregnancy, to provide information about how to block mother-to-infant transmission of HBV in chronic HBV-infected fertile women.

All patients were chronic HBV-infected fertile women from our outpatient department who either intended to become pregnant or were already in early pregnancy (with a gestational age of less than 12 wk). Three groups of patients were considered: (1) those who were on NA treatment and could not stop treatment; (2) those who had never taken any NA treatment, with alanine aminotransferase (ALT) > 2 times the upper limit of normal (ULN) for the reference range, HBV DNA > 1 × 105 copies/mL, but failed the traditional liver protection and enzyme reducing treatment; and (3) those who had received NA treatment, but later had virological breakthrough and liver function rebound without LAM drug-resistance. If patients from the above groups planned to become pregnant or had an accidental pregnancy and agreed to LAM treatment after thorough communication and consideration, they were included in this study after providing their written, informed consent.

All participants took screening tests before or in early pregnancy to rule out infection with hepatitis C virus, hepatitis delta virus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), syphilis, toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex. In this way, these tests helped to exclude any potentially hereditary diseases and any other diseases that needed to be treated. Furthermore, all participants routinely took folic acid before or during early pregnancy to prevent embryonic neural tube defects.

All participants undertook routine screening tests, and additionally liver function and HBV serology (HBV markers and HBV DNA) were measured every 12 wk. All adverse events that occurred during pregnancy and all neonatal abnormalities were recorded. The rate of blocking vertical transmission of HBV was also determined.

All infants received passive-active immunoprophylaxis with 200 IU hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) and three doses of 10 μg hepatitis B vaccines (0-1-6 mo) according to the guidelines for the prevention and treatment of chronic hepatitis B[7]. One month later, after all vaccinations (7-8 mo), liver function and HBV serology were measured again to evaluate the blocking rate. All infants underwent routine physical examination, hearing screening, and tests for congenital phenylketonuria and hypothyroidism. All neonatal abnormities were observed for up to 2 years.

Liver function and HBV serology were tested in the hospital’s clinical laboratory. HBV DNA was detected with an HBV real-time PCR amplification kit from Kehua Biological Company (Shanghai, China), which can detect HBV DNA at levels as low as 500 copies/mL. HBV markers were detected by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (Abbot Labs, North Chicago, IL, United States) on an ARCHITECT i2000 automatic immunoassay analyzer (Abbott) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Hearing screening was performed with the ECHO-SCREEN from Madsen Company (Germering, Germany). Heel blood was taken on filter paper from the infants after 72 h of breastfeeding, and specimens were sent to the Beijing Neonatal Diseases Screening Center to rule out congenital phenylketonuria and hypothyroidism.

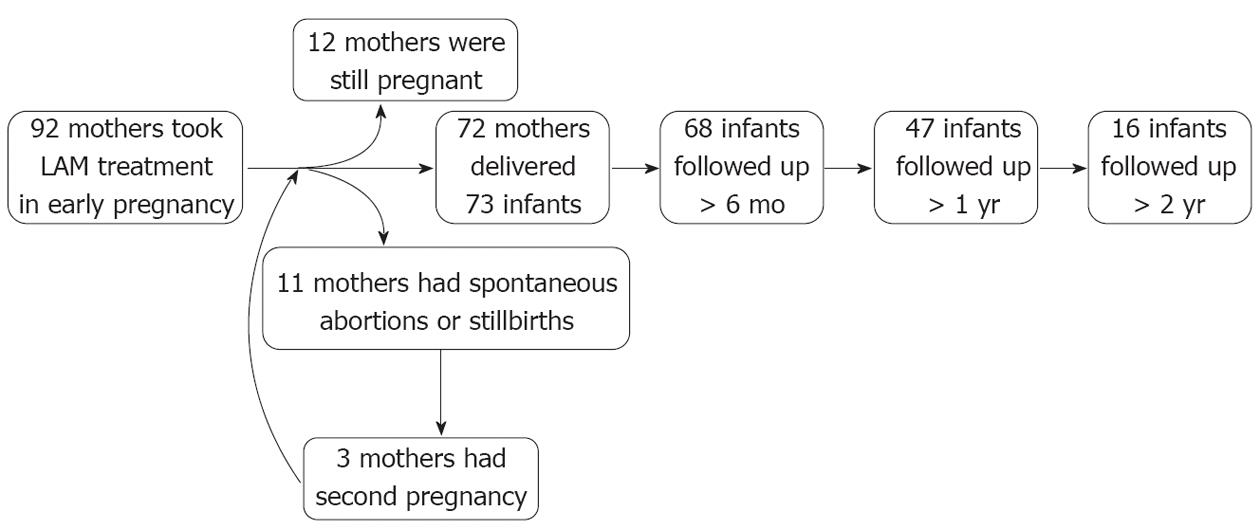

From January 1, 2007 to December 31, 2011, 92 HBV-infected women took LAM treatment before or during early pregnancy. Of these, one mother underwent in vitro fertilization with the transfer technique and later delivered twin infants. By the end of 20 wk’ gestational age, 11 fetuses aborted, and 3 mothers had a second pregnancy after initial abortion. Ultimately, 72 mothers delivered 73 live infants, of whom 68 infants were followed-up for more than 6 mo, 47 were followed-up for more than 1 year, and 16 were followed-up for more than 2 years. At the end of follow-up, 12 mothers were still pregnant (Figure 1).

Table 1 summarizes the clinical information for the mothers who chose lamivudine treatment before or in early pregnancy, including their demographic characteristics, HBV infection status, and treatment history. All participants were chronic hepatitis B patients, except for 2 cases with compensated cirrhosis, and none of the participants were HBV carriers with normal liver function. Most cases had a history of NA treatment before pregnancy; therefore, only 16 cases (17.4%) had HBV DNA > 105 copies/mL in early pregnancy. Of these 2 cirrhosis patients, one had refused to take any antiviral treatment despite a long history of abnormal liver function due to her concerns about the safety of NA drugs during pregnancy. However, when she later developed cirrhosis, she started to take LAM treatment and became pregnant; the other patient had concomitant autoimmune hepatitis and was taking ursodesoxycholic acid in addition to adefovir dipivoxil, and was later switched to LAM treatment before pregnancy. In early pregnancy, she ceased ursodesoxycholic acid treatment. In addition, 2 cases had previous peripheral neuropathy or myopathy when they took interferon and telbivudine (LdT) combination treatment; both switched to LAM treatment and later became pregnant.

| Treated population (n = 92) | |

| Average age (yr) | 30.5 ± 3.1 |

| Primipara | 88 (95.7) |

| Cirrhosis | 2 (2.2) |

| HBeAg positivity rate | 74 (80.4) |

| HBV DNA > 105 copies/mL in early pregnancy | 16 (17.4) |

| Treatment before pregnancy | |

| Naive | 15 (16.3) |

| LAM | 41 (44.6) |

| ADV | 28 (30.4) |

| LAM→ADV | 3 (3.3) |

| ETV | 2 (2.2) |

| ETV→ADV | 1 (1.1) |

| IFN + LdT | 2 (2.2) |

Fetal monitoring during pregnancy: Among the 92 women who took LAM treatment in early pregnancy, there were 95 pregnancies. Before 20 wk’ gestational age, 4 cases had a threatened abortion, but symptoms of miscarriage disappeared following aggressive treatment; 11 had developmental arrest or natural abortion, with an abortion rate of 11.6%. Ultimately, 72 mothers delivered 73 live infants; 3 had developmental retardation monitored with ultrasound but development later normalized after improving the mothers’ nutritional status and intravenous hydration. There were no other fetal developmental abnormalities reported and no stillbirths.

Monitoring mothers during pregnancy and the perinatal period: All maternal adverse events and laboratory abnormalities during pregnancy and the perinatal period are summarized in Table 2. The top 3 adverse events for mothers during pregnancy were vaginitis (16.7%), gestational diabetes (8.3%), and arrhythmia or abnormal electrocardiogram (5.6%). Only one case had 1-2 degree elevation of the creatine kinase (CK) level (195 U/L), and none of the other adverse events could be associated with LAM treatment. Abnormal ALT levels (≥ 2 × ULN) occurred in 16 cases (22.2%). Of these, 15 cases were in naïve patients without previous antiviral treatment who took LAM treatment only due to abnormal liver function in early pregnancy. The other case stopped LAM treatment before pregnancy and later developed severe hepatitis in early pregnancy, after which LAM was restarted, and her ALT level soon became normal, with her HBV DNA below 500 copies/mL.

| Adverse events | Cases | |

| Pregnancy | Vaginitis | 12 (16.7) |

| Gestational diabetes | 6 (8.3) | |

| Arrhythmia/abnormal ECG | 4 (5.6) | |

| Nausea and vomiting | 3 (4.2) | |

| Common cold | 3 (4.2) | |

| Oligohydramnios | 3 (4.2) | |

| Polyhydramnios | 2 (2.8) | |

| Greater than moderate anemia (Hb < 9 g/L) | 2 (2.8) | |

| Placenta previa | 2 (2.8) | |

| Inguinal hernia | 1 (1.4) | |

| Hypothyroidism | 1 (1.4) | |

| ALT ≥ 2 × ULN | 16 (22.2) | |

| HBV DNA breakthrough | 6 (8.3) | |

| Elevated total bilirubin | 2 (2.8) | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 (2.8) | |

| Elevated CK (1-2 degrees) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Perinatal period | Premature rupture of the membranes | 8 (11.1) |

| Preterm | 5 (6.9) | |

| Meconium staining of the amniotic fluid 2-3 degrees | 4 (5.6) | |

| Antepartum hemorrhage | 3 (4.2) | |

| Placenta accreta | 1 (1.4) |

However, another patient who took LAM treatment in early pregnancy decreased her HBV DNA by only 1.32 log in 12 wk, after which she was switched to LdT treatment from week 26. In addition, 6 cases had HBV DNA breakthrough with a LAM resistance rate of 8.3%; of these, 3 cases had HBV DNA rebound to above 106 copies/mL, and ADV was added from week 28. For the other 3 cases, ADV was added postpartum. The top 3 adverse events for mothers during the perinatal period were premature rupture of the membranes (11.1%), preterm delivery (6.9%), and meconium staining of the amniotic fluid (5.6%). There were no cases of postpartum hemorrhage or perinatal mortality. In addition, HBV DNA was monitored in mothers antepartum, and 63 cases (87.5%) had HBV DNA below 500 copies/mL.

Of the 92 mothers who took LAM treatment before or in early pregnancy, 72 delivered 73 live infants. Only 3 infants (4.1%) were low birth weight (birth weight < 2500 g); all the other infants had normal weights. None of the infants had abnormal hearing, congenital phenylketonuria, or hypothyroidism on testing. Of the 73 infants, 68 were followed-up for no less than 6 mo, while 47 were followed-up for more than 1 year, and 16 were followed-up for more than 2 years. Two infants were found to have abnormalities postpartum: 1 had 2 scalp hemangiomas (1.5 cm × 1.5 cm and 1.5 cm × 2.0 cm, respectively), which did not change in size until 7 mo, when the parents planned to arrange surgery for the infant; the other infant had early cerebral palsy at 8 mo, but with rehabilitation training, the infant’s motor functions became totally normal at 2 years of age. Sixteen babies were followed up for 2 to 4 years, and showed no signs of abnormal intelligence or growth.

Of the 73 live infants, 68 completed all of the examinations required for evaluating if there was mother-to-infant transmission. Vertical transmission was successfully blocked in 66 infants, for a blocking rate of 97.1%. One mother took LAM every other day by herself because she was concerned about LAM’s influence on the infant. She later developed virological breakthrough with HBV DNA increasing to 6.38 × 107 copies/mL. The other mother, who had HBV DNA of 3.6 × 103 copies/mL antepartum, experienced HBV-S mutation during treatment, resulting in blocking failure (the infant had HBsAg(-), HBV DNA(+) and abnormal ALT levels at both 7 mo and 1 year).

HBV infection is a serious public health problem worldwide. According to WHO statistics, about 5% of mothers are chronic HBV carriers[8], and the hepatitis B surface antigen positivity rate among fertile women in some high epidemic areas, such as Africa and South Asia, can be as high as 9.2%-15.5%[9-11]. About one-third of HBV-infected women enter into the immune clearance phase before or during pregnancy, with a high HBV DNA load and abnormal ALT levels. They are not only faced with a high risk of mother-to-infant transmission, but they also have an increased chance of hepatic disease exacerbation during pregnancy, threatening the safety of both mother and infant[12-14]. It is currently not recommended for chronic HBV-infected fertile women who are not pregnant to take interferon or NA treatment, in line with the guidelines for the prevention and treatment of chronic hepatitis B[7]. The antiviral efficacy of interferon is limited, and several side effects hinder its use, resulting in treatment failure. NA treatment alone results in only 20% of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-positive patients achieving HBeAg seroconversion, with only 12% able to stop treatment with a sustained virological response[15]. Therefore, many chronic HBV-infected fertile women become pregnant during treatment.

It is very dangerous for pregnant women to stop taking antiviral treatment during pregnancy when they have not met the withdrawal standard, as it may exacerbate liver disease, threatening the safety of both mother and infant. However, the safety of infants exposed to antiviral drugs in utero throughout the entire pregnancy is of particular concern, especially in early pregnancy, which is vital for fetal development. Although LAM is already approved as an optional antiviral drug for use in pregnancy, and several studies have reported its safety in late pregnancy[1-3], all of the studies regarding its safety before or during early pregnancy come from HIV-infected pregnant women[16]. Furthermore, most of these patients received combination therapy. So far, there have been very few reports about the safety of LAM treatment in chronic HBV-infected women before or during early pregnancy, and systematic observations have been scarce[4-6,17].

The present study showed that the abortion rate for HBV-infected women who took LAM treatment in early pregnancy was 11.6%, which was not higher than that of non HBV-infected mothers or HBV-infected mothers according to previous reports (11%-16% and 16.7%-21.9%, respectively)[6,18,19]. Overall, 72 mothers delivered 73 live infants; none were stillborn. Three fetuses had developmental retardation during pregnancy monitoring, although their development later normalized after treatment; no other fetal developmental abnormalities were reported. Only 4.1% of infants had low birth weight, which was similar to that of women without or with HBV infection according to previous reports (2.7%-7.8% and 5.0%-10.4%, respectively)[20]. None of the infants had abnormal hearing, congenital phenylketonuria, or hypothyroidism on testing. Two infants were found to have abnormalities (scalp hemangiomas and early cerebral palsy), with a congenital abnormity rate of 2.7%, which is similar to the data from HIV-infected women (3.1%) who took antiretroviral treatment (including LAM) in early pregnancy from 1989 to 2011[16]. According to the literature, the congenital abnormality rates for infants born to mothers without or with HBV infection were 5.1%-6.3% and 7.2%-10%, respectively[6,20,21]. The present report suggests that it is safe for fetuses to be exposed to LAM in utero for the entire pregnancy or in early pregnancy, and it does not affect fertilization or fetal development or result in congenital abnormities. Neither does it affect postnatal development.

The most common adverse event for mothers during pregnancy and the perinatal period was vaginitis (16.7%), among which 7 were vulvovaginal candidiasis (9.7%) and 5 were bacterial vaginosis. However, vaginitis is a common genital infectious disease in pregnant and non-pregnant women and the incidence of vaginitis in our study group was similar to that reported in the literature; it has been reported that the detection rate of candidal vaginitis in pregnant women is about 10%[22,23], and the incidence of bacterial vaginosis among Asian women is 6.1%[24]. Other adverse events included gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, oligohydramnios, polyhydramnios, placenta previa, anemia, pre-eclampsia, premature rupture of the membranes, and preterm delivery. The incidence of the above adverse events was not higher than that of mothers without or with HBV infection according to previous reports[25-29]. Only one patient had 1-2 degree elevation of serum CK levels, and none of the other adverse events could be associated with LAM treatment. These results suggest that it is safe for HBV-infected pregnant women to take LAM treatment in early pregnancy or throughout the entire pregnancy.

Pregnancy can not only increase the burden on the liver, but it can also increase adrenal cortical hormone levels, boosting HBV replication and activation of hepatitis B. Therefore, for HBV-infected women, the average increase in the HBV DNA level was 0.4 log in late pregnancy or postpartum, and 25% of HBeAg(-) pregnant women had an increase of HBV DNA > 1 log, accompanied by elevation of ALT levels in late pregnancy or postpartum[13,29]. The incidence of severe hepatitis during the perinatal period (in late pregnancy and one month postpartum) was much higher than in nonpregnant women[12-14,30]. In the present study, all mothers without previous antiviral treatment maintained normal ALT levels throughout the entire pregnancy, and none of them had severe hepatitis. Fifteen mothers who took NA treatment previously had abnormal ALT levels in early pregnancy, but ALT normalized after LAM treatment, and the pregnancy continued. Interestingly, one mother stopped LAM treatment before pregnancy and later developed severe hepatitis in early pregnancy. However, all symptoms later disappeared, liver function normalized and the HBV DNA load became undetectable when she restarted LAM. In addition, 87.5% of patients had HBV DNA below 500 copies/mL antepartum, and the LAM resistance rate was only 8.3% during pregnancy. This suggests that LAM can effectively suppress HBV DNA replication in HBV-infected pregnant women, maintain normal liver function, and lower the incidence of hepatic disease during pregnancy, improving the prognosis of HBV-infected pregnant women.

According to previous reports, for infants born to HBeAg-positive mothers, even after they received passive-active immunoprophylaxis with HBIG and three doses of hepatitis B vaccines, vertical transmission was not blocked in 7%-16.3%[31]. For mothers with an increased HBV DNA load, vertical transmission was not blocked in as many as 23.4%-32% of infants[32]. In the present study, 80.4% of mothers was HBeAg-positive, and all of them had a high HBV DNA load before LAM treatment. However, 63 (87.5%) mothers had HBV DNA below 500 copies/mL antepartum, and the blocking rate was 97.1%; blocking failed in only 2 cases. The first mother had poor compliance, resulting in HBV DNA breakthrough, while the other had an HBV-S mutation during treatment, resulting in failure of vaccine immunization. These results suggest that LAM treatment could increase the vertical transmission blocking rate in HBeAg-positive mothers.

This study suggests that it is safe and effective for chronic HBV-infected pregnant women to take LAM treatment in early pregnancy. Treatment does not increase complications or adverse events for mothers during pregnancy or the perinatal period, has no effect on fertilization or embryonic development, and does not increase the incidence of congenital abnormalities in infants. Furthermore, it increases the blocking rate of mother-to-infant transmission. In conclusion, the benefits of taking LAM treatment in early pregnancy outweigh the risks. However, the sample size of this study was small, and the follow-up time was limited; both need to be optimized in later studies to provide greater insight.

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is prevalent throughout the world; 2 billion people have been or are infected with HBV worldwide, with 350 million people having chronic infections. Each year, more than 1 million people die of HBV-related liver failure, cirrhosis, or primary hepatic carcinoma. Interferon and nucleos(t)ide analogs (NAs) are available for the antiviral treatment of hepatitis B. However, the efficacy of interferon is suboptimal, and interferon is associated with scores of adverse effects, so that many patients fail or cannot tolerate treatment. Treatment with NAs requires long-term persistence, as in the case of human immunodeficiency virus; stopping the medicine frequently leads to relapse of the disease. As women undergoing treatment cannot halt the medicine at will, pregnancy often occurs during the on-treatment period. However, the safety profile of NAs has not been verified. The goal of this study was to observe the safety profile of lamivudine for the mother and fetus throughout the entire pregnancy.

In recent years, with many studies evaluating the efficacy and safety profile, the administration of lamivudine and other NAs during the third trimester to block HBV transmission has been a hot topic. However, studies regarding lamivudine treatment during the first trimester or the entire period of pregnancy are scarce.

This study observed adverse events throughout the entire period of pregnancy in women taking lamivudine, including abortion, ectopic pregnancy, and complications related to pregnancy. The study also observed intrauterine deformations of the fetus and abnormalities after birth in detail and maintained long-term follow-up of some neonates.

The study provides preliminary evidence of the safety profile for pregnant women taking lamivudine. It also sets an example for further studies exploring the safety profile of NAs in pregnant women.

The manuscript describes safety of lamivudine treatment in early pregnancy. They compared maternal and infant abnormality, HBV DNA level and mutations, and blocking rates of mother-to infant transmission between cases with and without lamivudine treatment. They concluded that lamivudine treatment in early treatment is safe. The study is important, because patients with HBV infection often show elevation of HBV DNA levels and may have alanine aminotransferase flare.

Peer reviewer: Yukihiro Shimizu, MD, PhD, Kyoto Katsura Hospital, 17 Yamada-Hirao, Nishikyo, Kyoto 615-8256, Japan

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

| 1. | Shi Z, Yang Y, Ma L, Li X, Schreiber A. Lamivudine in late pregnancy to interrupt in utero transmission of hepatitis B virus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:147-159. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Han L, Zhang HW, Xie JX, Zhang Q, Wang HY, Cao GW. A meta-analysis of lamivudine for interruption of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4321-4333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Xu WM, Cui YT, Wang L, Yang H, Liang ZQ, Li XM, Zhang SL, Qiao FY, Campbell F, Chang CN. Lamivudine in late pregnancy to prevent perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus infection: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:94-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Loreno M, Bo P, Senzolo M, Cillo U, Naoumov N, Burra P. Successful pregnancy in a liver transplant recipient treated with lamivudine for de novo hepatitis B in the graft. Transpl Int. 2005;17:730-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fota-Markowska H, Modrzewska R, Borowicz I, Kiciak S. Pregnancy during lamivudine therapy in chronic hepatitis B--case report. Ann Univ Mariae Curie Sklodowska Med. 2004;59:1-3. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Su GG, Pan KH, Zhao NF, Fang SH, Yang DH, Zhou Y. Efficacy and safety of lamivudine treatment for chronic hepatitis B in pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:910-912. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Chinese Society of Hepatology and Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association. The guideline of prevention and treatment for chronic hepatitis B (2010 version). Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi. 2011;19:13-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hepatitis B and breastfeeding. Indian Pediatr. 1997;34:518-520. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Makuwa M, Caron M, Souquière S, Malonga-Mouelet G, Mahé A, Kazanji M. Prevalence and genetic diversity of hepatitis B and delta viruses in pregnant women in Gabon: molecular evidence that hepatitis delta virus clade 8 originates from and is endemic in central Africa. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:754-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liu CY, Chang NT, Chou P. Seroprevalence of HBV in immigrant pregnant women and coverage of HBIG vaccine for neonates born to chronically infected immigrant mothers in Hsin-Chu County, Taiwan. Vaccine. 2007;25:7706-7710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lin CC, Hsieh HS, Huang YJ, Huang YL, Ku MK, Hung HC. Hepatitis B virus infection among pregnant women in Taiwan: comparison between women born in Taiwan and other southeast countries. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jonas MM. Hepatitis B and pregnancy: an underestimated issue. Liver Int. 2009;29 Suppl 1:133-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Söderström A, Norkrans G, Lindh M. Hepatitis B virus DNA during pregnancy and post partum: aspects on vertical transmission. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35:814-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Leung N. Chronic hepatitis B in Asian women of childbearing age. Hepatol Int. 2009;3 Suppl 1:24-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Marcellin P, Asselah T, Boyer N. Treatment of chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:333-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry Steering Committee. Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry International. Interim Report for 1 January 1989 through 31 July 2011. 2011-12-1. Available from: http: //www.apregistry.com/who.htm. |

| 17. | Tomasiewicz K, Modrzewska R, Krawczuk G, Lyczak A. Lamivudine therapy for chronic hepatitis B virus infection and pregnancy: a case report. Int J Infect Dis. 2001;5:115-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Everett C. Incidence and outcome of bleeding before the 20th week of pregnancy: prospective study from general practice. BMJ. 1997;315:32-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Reddick KL, Jhaveri R, Gandhi M, James AH, Swamy GK. Pregnancy outcomes associated with viral hepatitis. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:e394-e398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Safir A, Levy A, Sikuler E, Sheiner E. Maternal hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus carrier status as an independent risk factor for adverse perinatal outcome. Liver Int. 2010;30:765-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tse KY, Ho LF, Lao T. The impact of maternal HBsAg carrier status on pregnancy outcomes: a case-control study. J Hepatol. 2005;43:771-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cotch MF, Hillier SL, Gibbs RS, Eschenbach DA. Epidemiology and outcomes associated with moderate to heavy Candida colonization during pregnancy. Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:374-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lisiak M, Kłyszejko C, Pierzchało T, Marcinkowski Z. Vaginal candidiasis: frequency of occurrence and risk factors. Ginekol Pol. 2000;71:964-970. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Goldenberg RL, Klebanoff MA, Nugent R, Krohn MA, Hillier S, Andrews WW. Bacterial colonization of the vagina during pregnancy in four ethnic groups. Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1618-1621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lobstein S, Faber R, Tillmann HL. Prevalence of hepatitis B among pregnant women and its impact on pregnancy and newborn complications at a tertiary hospital in the eastern part of Germany. Digestion. 2011;83:76-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wong S, Chan LY, Yu V, Ho L. Hepatitis B carrier and perinatal outcome in singleton pregnancy. Am J Perinatol. 1999;16:485-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lao TT, Chan BC, Leung WC, Ho LF, Tse KY. Maternal hepatitis B infection and gestational diabetes mellitus. J Hepatol. 2007;47:46-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | To WW, Cheung W, Mok KM. Hepatitis B surface antigen carrier status and its correlation to gestational hypertension. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;43:119-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lin HH, Chen PJ, Chen DS, Sung JL, Yang KH, Young YC, Liou YS, Chen YP, Lee TY. Postpartum subsidence of hepatitis B viral replication in HBeAg-positive carrier mothers. J Med Virol. 1989;29:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Nguyen G, Garcia RT, Nguyen N, Trinh H, Keeffe EB, Nguyen MH. Clinical course of hepatitis B virus infection during pregnancy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:755-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wiseman E, Fraser MA, Holden S, Glass A, Kidson BL, Heron LG, Maley MW, Ayres A, Locarnini SA, Levy MT. Perinatal transmission of hepatitis B virus: an Australian experience. Med J Aust. 2009;190:489-492. [PubMed] |

| 32. | del Canho R, Grosheide PM, Mazel JA, Heijtink RA, Hop WC, Gerards LJ, de Gast GC, Fetter WP, Zwijneberg J, Schalm SW. Ten-year neonatal hepatitis B vaccination program, The Netherlands, 1982-1992: protective efficacy and long-term immunogenicity. Vaccine. 1997;15:1624-1630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |