Published online Mar 28, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i12.1414

Revised: September 30, 2011

Accepted: February 27, 2012

Published online: March 28, 2012

Pseudomelanosis duodeni (PD) is a rare dark speckled appearance of the duodenum associated with gastrointestinal bleeding, hypertension, chronic heart failure, chronic renal failure and consumption of different drugs. We report four cases of PD associated with chronic renal failure admitted to the gastroenterology outpatient unit due to epigastric pain, nausea, melena and progressive reduction of hemoglobin index. Gastroduodenal endoscopy revealed erosions in the esophagus and stomach, with no active bleeding at the moment. In addition, the duodenal mucosa presented marked signs of melanosis; later confirmed by histopathological study. Even though PD is usually regarded as a benign condition, its pathogenesis and clinical significance is yet to be defined.

- Citation: Costa MHM, Pegado MDGF, Vargas C, Castro MEC, Madi K, Nunes T, Zaltman C. Pseudomelanosis duodeni associated with chronic renal failure. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(12): 1414-1416

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i12/1414.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i12.1414

Melanosis duodeni was first described in 1976 and refers to a rare endoscopic appearance of discrete speckled black pigmentation of duodenal mucosa, which was initially postulated to represent a form of stored iron[1]. The term melanosis gives a false idea that the pigment is produced by melanocytes, justifying renaming this endoscopic finding as pseudomelanosis duodeni (PD)[2]. Nevertheless, the clinical significance of this condition is yet to be established. PD is more common in the sixth and seventh decade of life with a female predominance. It has been postulated to be associated with gastric hemorrhage, certain chronic illnesses, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, as well as various medications, such as sulfur-containing antihypertensive agents and ferrous sulfate[3-5].

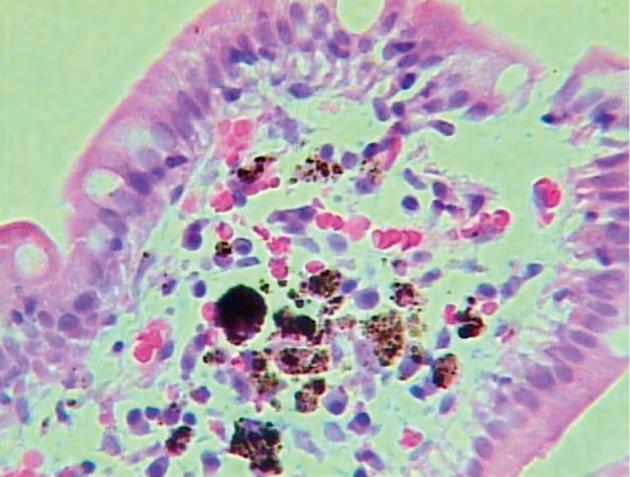

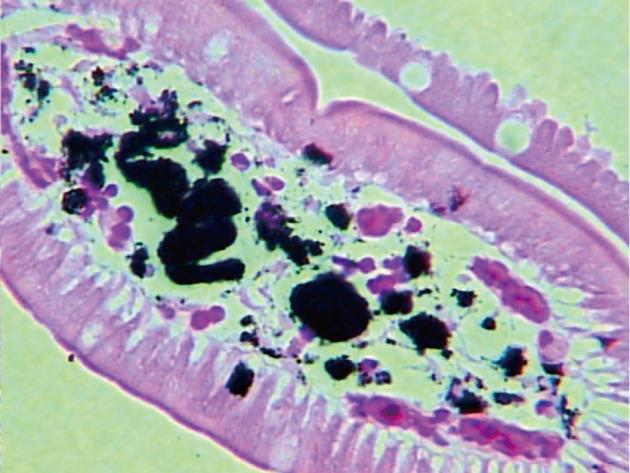

A 66-year-old woman was admitted with a history of melena and a progressive decrease of hemoglobin index. She presented with a history of diabetes mellitus and systemic arterial hypertension for > 30 years, with a diagnosis of chronic renal failure in the last 6 mo, treated with hemodialysis. She was on long-term treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, furosemide, ferrous sulfate, folic acid and insulin. Gastroduodenal endoscopy was performed and revealed multiple superficial erosions in the stomach without signs of recent bleeding. In addition, in the duodenal mucosa, pigmented lesions with a speckled pattern were evident (Figure 1). Biopsies revealed numerous macrophages containing brown pigment granules in their cytoplasm within the lamina propria (Figure 2). Staining of the specimen with Masson Fontana stain demonstrated iron-containing deposits inside the macrophages (Figure 3).

A 37-year-old woman with a history of renal transplantation (hypertensive nephropathy) had been previously treated with furosemide, propranolol, hydralazine and ferrous sulfate. She was referred to the gastroenterology section due to classical gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms. She was submitted to gastroduodenal endoscopy that revealed reflux esophagitis and diffuse, multiple, dark brown spots in the duodenum. Biopsies were taken and light microscopy confirmed the presence of brown pigment granules in the lamina propria.

A 70-year-old woman with diabetes and long-term systemic arterial hypertension developed chronic renal failure that was initially treated conservatively with calcium channel blockers, propranolol, α-methyldopa, furosemide and glibenclamide. She underwent a left nephrectomy due to nephrolithiasis. Progressive reduction of hemoglobin index was observed during follow-up, therefore, gastroduodenal endoscopy was performed, revealing multiple non-actively bleeding superficial gastric erosions and pigmented lesions in the duodenum. Biopsies were collected and histopathological examination showed features of PD.

A 30-year-old woman with diabetes started complaining of epigastric pain, nausea and vomiting 1 mo after renal and pancreatic transplantation (diabetic nephropathy). She had been previously taking insulin, and after the transplant, she started tracolimus, mycophenolate and corticosteroid therapy. Gastroduodenal endoscopy revealed cytomegalovirus (CMV) esophagitis and multiple small pigmented duodenal spots. Biopsies were taken and histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of PD. Another gastroduodenal endoscopy was performed after CMV treatment, and demonstrated total regression of the esophageal lesions but no changes in the aspect of the duodenal mucosa.

PD represents a fine granular brown material inside the macrophage lysosomes in the lamina propria around the tips of the duodenal villi, detected by histochemical staining and electron microscopy. It has been postulated that this heterogeneous pigment may represent a deposit of melanin-like substances, hemosiderin, lipomelanin and lipofuscin[6,7]. Even though iron (ferrous sulfide) is the main pigment compound, varying amounts of sulfur, calcium, potassium, aluminum, magnesium and silver can also be detected[5,8]. The color of the pigment could represent various degrees of auto-oxidation of ferrous sulfide[2,6].

The pathogenesis still remains unclear. It could be related to iron deposition secondary to intramucosal hemorrhage or impaired intramucosal iron transport after oral ferrous sulfate supplementation[6,9]. Iron sulfide storage can also be a product of an acquired inherent defect in macrophage metabolism. In that regard, the pigment present in the duodenal mucosa has also been shown to be partially associated with impaired macrophage metabolism of drugs containing cyclic compounds such as phenols, indoles and skatoles[8].

All four patients had undergone previous gastroduodenal endoscopy without any pathological findings, suggesting that this condition might be acquired rather than congenital, which is in keeping with previous reports[5]. Importantly, it must be stressed that this entity might be identified histologically even before it becomes endoscopically visible, making it difficult to establish a temporal association between disease onset and endoscopic manifestation[10].

In this report, all patients were female, with chronic renal failure, and taking antihypertensive drugs. Of note, only two patients were taking oral iron supplements. The biopsy specimens were positive for hematoxylin and eosin and Masson-Fontana stains but not reactive for Pearl’s stain, suggesting a melanin-like compound. Although Pearl’s stain is a classic method for demonstrating iron in tissues, there is a possibility of a false-negative reaction if an iron oxide compound is present instead of iron sulfide[11,12].

In conclusion, these findings suggest that the duodenal involvement can occur in the absence of a history of oral iron supplementation. Importantly, although the long-term clinical impact of these depositions remains unclear, these endoscopic findings still do not require any specific treatment or recommended follow-up.

Peer reviewers: Ross C Smith, Professor, Department of Surgery, University of Sydney, Royal North Shore Hospital, St Leonards, New South Wales 2065, Australia; Keiji Hirata, MD, Surgery 1, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, 1-1 Iseigaoka, Yahatanishi-ku, Kitakyushu 807-8555, Japan

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Xiong L

| 1. | Bisordi WM, Kleinman MS. Melanosis duodeni. Gastrointest Endosc. 1976;23:37-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Banai J, Fenyvesi A, Gonda G, Petö I. Melanosis jejuni. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:432-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Cantu JA, Adler DG. Pseudomelanosis duodeni. Endoscopy. 2005;37:789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | eL-Newihi HM, Lynch CA, Mihas AA. Case reports: pseudomelanosis duodeni: association with systemic hypertension. Am J Med Sci. 1995;310:111-114. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Ghadially FN, Walley VM. Pigments of the gastrointestinal tract: a comparison of light microscopic and electron microscopic findings. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1995;19:213-219. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Rex DK, Jersild RA. Further characterization of the pigment in pseudomelanosis duodeni in three patients. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:177-182. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kang JY, Wu AY, Chia JL, Wee A, Sutherland IH, Hori R. Clinical and ultrastructural studies in duodenal pseudomelanosis. Gut. 1987;28:1673-1681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Leong S. Pseudomelanosis duodeni and the controversial pigment--a clinical study of 4 cases. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1992;21:394-398. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Gupta TP, Weinstock JV. Duodenal pseudomelanosis associated with chronic renal failure. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:358-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Giusto D, Jakate S. Pseudomelanosis duodeni: associated with multiple clinical conditions and unpredictable iron stainability - a case series. Endoscopy. 2008;40:165-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pounder DJ. The pigment of duodenal melanosis is ferrous sulfide. Gastrointest Endosc. 1983;29:257. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Yamase H, Norris M, Gillies C. Pseudomelanosis duodeni: a clinicopathologic entity. Gastrointest Endosc. 1985;31:83-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |