Published online Dec 7, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i45.5028

Revised: May 2, 2011

Accepted: May 9, 2011

Published online: December 7, 2011

Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract that is defined by relapsing and remitting episodes. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) appears to play a central role in the pathophysiology of the disease. Standard therapies for inflammatory bowel disease fail to induce remission in about 30% of patients. Biological therapies have been associated with an increased incidence of infections, especially infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). Thalidomide is an oral immunomodulatory agent with anti-TNF-α properties. Recent studies have suggested that thalidomide is effective in refractory luminal and fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Thalidomide costimulates T lymphocytes, with greater effect on CD8+ than on CD4+ T cells, which contributes to the protective immune response to Mtb infection. We present a case of Crohn’s disease with gastric, ileal, colon and rectum involvement as well as steroid dependency, which progressed with loss of response to infliximab after three years of therapy. The thorax computed tomography scan demonstrated a pulmonary nodule suspected to be Mtb infection. The patient was started on thalidomide therapy and exhibited an excellent response.

- Citation: Leite MR, Santos SS, Lyra AC, Mota J, Santana GO. Thalidomide induces mucosal healing in Crohn's disease: Case report. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(45): 5028-5031

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i45/5028.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i45.5028

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract that is defined by relapsing and remitting episodes[1]. The inflammatory process is characterized by increased production of proinflammatory cytokines[2]. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) plays a central role in the pathogenesis of the disease[3].

Over the past few decades, medical therapy for CD has progressed significantly with immunomodulating agents such as azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, methotrexate, tacrolimus and cyclosporin, and biological agents such as infliximab, adalimumab and certolizumab[1]. Nevertheless, the use of biological therapies has been associated with an increased incidence of infections, especially infection by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb)[4].

Thalidomide is an oral immunomodulatory agent with anti-TNF-α properties[5,6]. Thalidomide increases the IFN-γ level and modulates several other cytokines as well, especially interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-12[2]. Recently, an open-label trial assessing the treatment of refractory CD reported response rates of 64% and 70% after a 12-wk course of thalidomide[7,8].

Thalidomide costimulates T lymphocytes, with greater effect on CD8+ than on CD4+ T cells, which contributes to the protective immune response to Mtb infection[9,10]. Results from four case reports, one clinical trial and one placebo-controlled trial suggest the use of thalidomide for central nervous system tuberculosis (TB) not responding to standard therapy is beneficial. Thalidomide should not be used for routine treatment, but it may be useful as a “salvage therapy” in patients with tuberculosis meningitides and tuberculomas that are not responding to anti-TB drugs or to high-dose corticosteroids[11].

We present the case of a 24-year-old CD patient, with gastric, ileal, colon and rectum involvement, as well as steroid dependency, which progressed with diminished response to infliximab after three years of therapy. A thoracic computed tomography scan revealed a pulmonary nodule suspected to be Mtb infection. He was started on thalidomide therapy and exhibited an excellent response.

A 24-year-old male was first diagnosed with CD at the age of 10 when he presented fever, arthralgia of large joints (knees and ankles), bloody diarrhea (more than 10 bowel movements/d) and a Harvey-Bradshaw Index of 13. Endoscopy showed involvement of gastric corpus, ileum and all segments of the colon and rectum.

Initially, he was prescribed 1 mg/kg per day steroid, 100 mg/d azathioprine and 2.5 g/d sulfasalazine by a pediatric gastroenterologist. After eight years, he presented signs of active inflammatory bowel disease, with imaging revealing CD activity in gastric tissue, ileal tissue, and all segments of the colon and rectum (Harvey-Bradshaw Index 15). He was started on therapy with infliximab 5 mg/kg and continued on 100 mg/d azathioprine. After 2 mo, the patient presented significant clinical improvement with reduced stool frequency of 3 bowel movements/d and remission of joint inflammation. Endoscopic evaluation showed reduction of inflammatory disease activity in all segments of the colon and rectum, as well as healing of gastric lesions. The Harvey-Bradshaw Index was 4 after infliximab treatment.

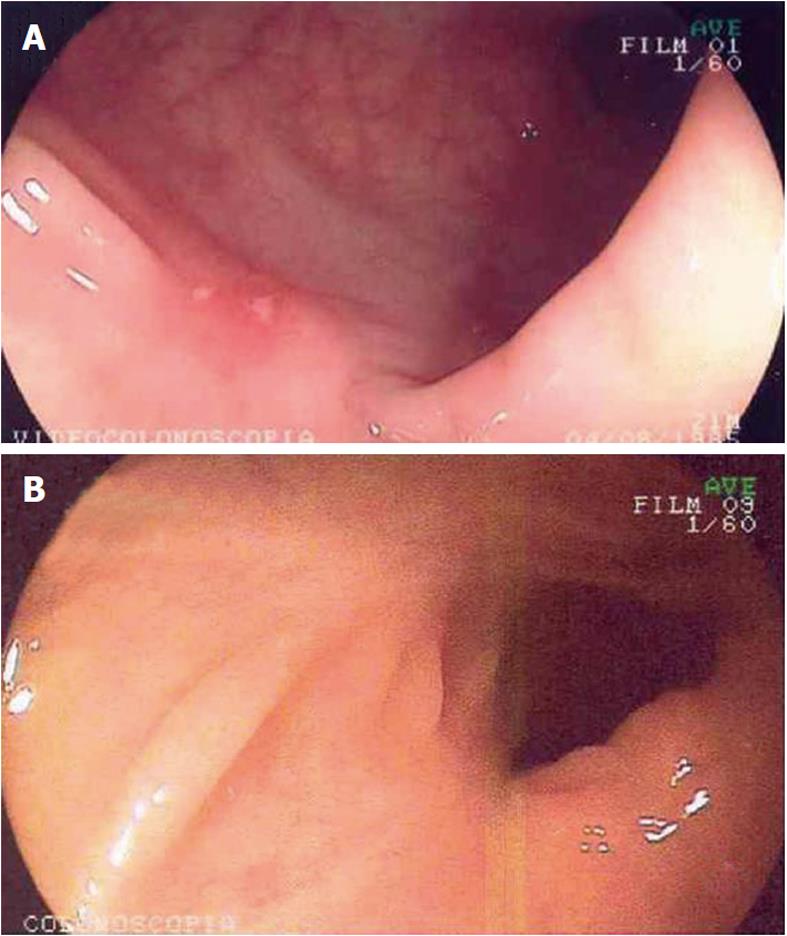

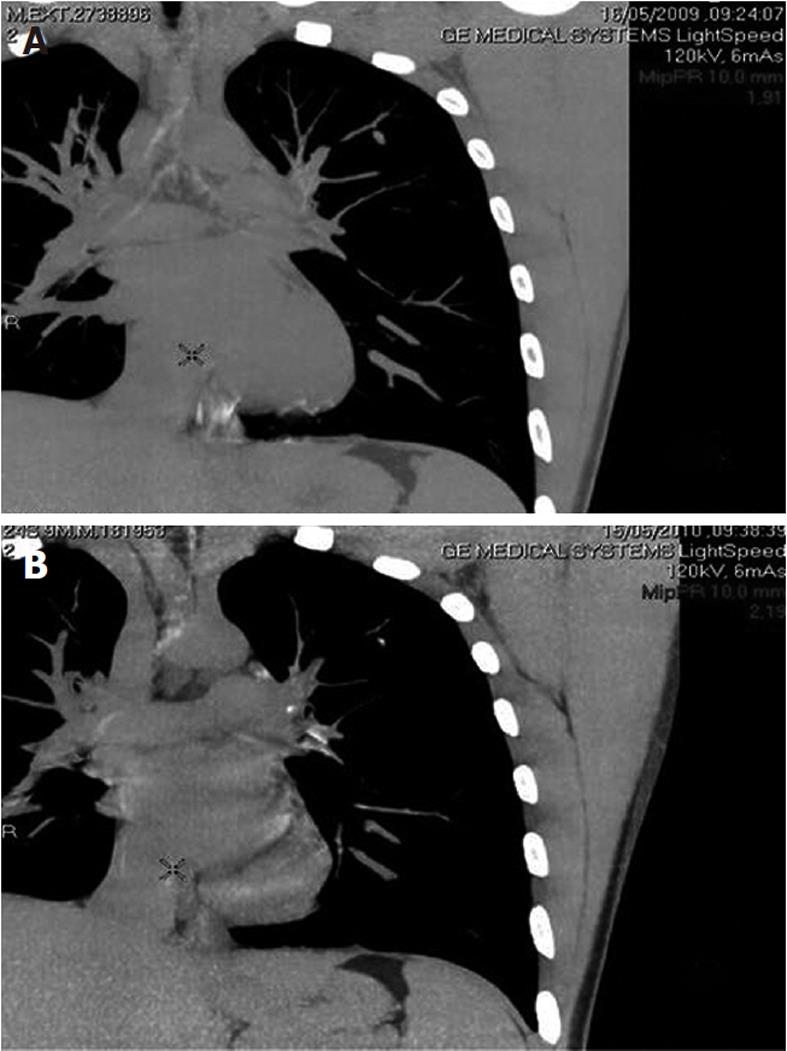

Six months after the first dose of infliximab, the patient relapsed with bloody diarrhea in 6-8 bowel movements/d and a Harvey-Bradshaw Index of 12. The infliximab dose was increased to 10 mg/kg, which controlled the disease activity and led to a Harvey-Bradshaw index of 2. After 3 years, the patient presented with worsening of disease. Imaging studies revealed inflammatory activity in the gastric body, sigmoid and descending colon (Figure 1A). Infliximab was discontinued, and the azathioprine dose was increased to 150 mg/d in combination with mesalazine 1.2 g/d. We opted not to introduce adalimumab due to the presence of a cavitary pulmonary nodule in the left upper lobe measuring 0.6 × 0.8 cm2 (Figure 2A). At that time, we suspected infectious pneumonia (fungal/mycobacterial), eosinophilic granuloma or vasculitis. As the lung nodule was not accessible to percutaneous or bronchoscopy biopsy, we opted for a conservative approach. Because we did not have a definitive diagnosis of pulmonary disease and because the patient presented with all the symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease, including diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss, arthralgia and a Harvey-Bradshaw Index of 15, we opted to introduce thalidomide.

Thalidomide was started at 100 mg/d, and the patient’s symptoms resolved, with initial improvement of abdominal pain and diarrhea between 1 and 4 mo (Harvey-Bradshaw Index 8) and complete remission of symptoms at 6 mo of therapy (Harvey-Bradshaw Index 3). The patient was asymptomatic, presenting 2-3 regular bowel movements/d and pasty stools, without blood or mucus. He denied abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting and complained of neuropathy. His weight increased by 10 kg. Laboratory tests showed normal inflammatory activity (CRP 3; ESR 2). Colonoscopy revealed scar tissue in sigmoid colon, descending, transverse, and ascending colon; and cecum; the ileocecal valve and terminal ileum showed ulceration, with thick fibrin interspersed with normal mucosa (Figure 1B). Control computerized tomography showed small (0.5 cm) calcified pulmonary nodules in the apico-posterior segment, which were suggestive of primary Mtb infection (Figure 2B).

Standard therapies for inflammatory bowel disease fail to induce remission in about 30% of patients[12]. Recent studies have suggested that thalidomide at doses varying from 50 to 300 mg/d is effective in refractory luminal and fistulizing CD[10,11]. The response appears to be fairly rapid, and the remission rate is 20%-40% after 12 wk of thalidomide therapy[13].

Considering the present case, a patient with long-standing CD with extensive involvement of the digestive tract who failed to respond to infliximab after 3 years of therapy and had a pulmonary nodule possibly resulting from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, it was necessary to offer an effective and safe therapy to avoid infection. New therapies are needed in the context of patients with inflammatory bowel disease and tuberculosis diagnosed or suspected before or after biological treatment. Thalidomide appears to be a good option in this situation, as in selected cases of Mtb infection of the central nervous system.

Wettstein and Meagher were the first authors to describe thalidomide therapy in a woman with complicated CD. The patient was treated with all of the current medication at the time, including total parenteral nutrition, metronidazole and cyclosporine, without success. Resolution of the disease was achieved using 300 mg thalidomide per day and maintenance of 100 mg per day until the date of publication of the case[14]. Vasiliauskas et al[8] published an open-label trial that evaluated the tolerance and efficacy of low dose thalidomide for the treatment of moderate to severe steroid-dependent CD in 12 males with CDAI ≥ 250 and ≤ 500. The patients were treated with thalidomide 50 mg/d during the first 6 mo, increasing to 100 mg/d until the completion of 1 year of treatment. Disease activity (CDAI) improved consistently in all patients during the first 4 wk, with a response rate of 58% and a remission rate of 17%. After 12 mo, 70% of patients had responded, and 20% achieved remission. All patients were able to reduce steroid dosage to less than 50% of the initial dose; 48% of patients discontinued the use of steroids[11]. Our patient also used low doses of thalidomide and is still in remission after 2 years of therapy without adverse events, which demonstrates that low doses of thalidomide appear to be well tolerated and effective over a period exceeding 12 wk.

Ehrenpreis et al[7] reported an open-label trial of 22 patients with refractory CD (CDAI > 200 and/or perianal disease) treated with thalidomide 200 mg/d (18 patients) or 300 mg/d (4 patients). Nine patients with luminal disease and 13 with fistulas were included. Sixteen patients completed 4 wk of treatment (12 clinical responses, 4 remissions). Of the patients who completed 12 wk of treatment, 14 met the criteria for clinical response, nine achieved remission. Mean CDAI before and after treatment was 371 (95-468) and 175 (30-468), respectively (P < 0.001)[10]. Of note, none of these previous studies described the results of thalidomide usage after a long period of treatment. We describe here the case report of a 24-year-old male maintained on thalidomide therapy for more than 2 years without loss of response.

Bariol et al[15] evaluated the safety and efficacy of thalidomide for symptomatic inflammatory bowel disease. Eleven patients (6 with CD, 4 with UC and 1 with indeterminate colitis) were treated with thalidomide 100 mg/d for 12 wk. Two patients were withdrawn from therapy after three weeks because of mood disorders. Of the remaining 9 patients, 8 responded to treatment (5 DC, 2 UC and 1 IC). The frequency of stools fell from 4.3 to 2.3 per day (P = 0.0012); stool consistency improved from 2.1 to 1.2 (P = 0.02); and mean CDAI decreased from 117 to 48 (P = 0.0008). Endoscopic inflammation, histological inflammation, CRP and ESR decreased significantly (P = 0.011, P = 0.03, P = 0.023 and P = 0.044, respectively). However, levels of serum TNF-α did not change[15]. Thalidomide acts partly by accelerating the degradation of TNF-α mRNA, resulting in decreased production of this cytokine by activated mononuclear cells. It has also been shown to inhibit NF-κB activation, thus suppressing transcription of other important inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-12 both in vitro and in vivo[16,17]. Thalidomide increases expression of the Th2-type cytokine IL-4 and decreases the helper to suppress T-cell ratio, effects that are likely to contribute to its efficacy in CD[18]. Furthermore, it has been shown to interfere with angiogenesis and to downregulate cell adhesion molecules such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), thought to be important in lymphocyte homing mechanisms in inflammatory bowel disease[19]. These multiple alternative mechanisms of action may be involved in thalidomide’s effectiveness in patients with severe disease refractory to conventional and biological agents, as was the case for the patient presented in this report.

Kane et al[20] reported a series of cases where thalidomide was a “salvage” therapy for patients with delayed hypersensitivity to infliximab. Four patients (two with active luminal disease and two with fistulous disease) were treated with thalidomide 200 mg/d and were evaluated monthly for 12 wk. One patient with a single perianal fistula had complete closure, and another had improvement in five perianal fistulas in 4 wk and closure in 12 wk. One patient had a CDAI decrease of 250 points in 4 wk. One patient was withdrawn from the study because of sedation after the first week of treatment. Reported side effects were sedation (4/4), hypertension (1/4) and peripheral neuropathy (1/4)[20]. Due to thalidomide’s toxicity it is recommended only in selected cases of refractory CD, as in our patient, when the benefits outweigh the risk of peripheral neuropathy, and there is strict and full adherence to the program of birth control, avoiding the risk of teratogenicity.

To our knowledge, this is the first case report of a patient presenting with a pulmonary nodule that could be M. tuberculosis infection who was treated with thalidomide to control severe CD after loss of response to biological therapy, with a favorable evolution. Therefore, thalidomide might be considered a therapeutic option in similar clinical situations.

Peer reviewer: Dr. Jörg C Hoffmann, MA, Priv, Doz, MD, Chief of the Medizinischen Klinik I, mit Schwerpunkt Gastroenterologie, Diabetologie, Rheumatologie und Onkologie, St. Marien-und St Annastiftskrankenhaus, Salzburger Straße 15, D67067 Ludwigshafen, Germany

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Zhang DN

| 1. | Michelassi F, Balestracci T, Chappell R, Block GE. Primary and recurrent Crohn's disease. Experience with 1379 patients. Ann Surg. 1991;214:230-238; discussion 238-240. [PubMed] |

| 2. | MacDonald TT, Hutchings P, Choy MY, Murch S, Cooke A. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interferon-gamma production measured at the single cell level in normal and inflamed human intestine. Clin Exp Immunol. 1990;81:301-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | van Dullemen HM, van Deventer SJ, Hommes DW, Bijl HA, Jansen J, Tytgat GN, Woody J. Treatment of Crohn's disease with anti-tumor necrosis factor chimeric monoclonal antibody (cA2). Gastroenterology. 1995;109:129-135. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Keane J, Gershon S, Wise RP, Mirabile-Levens E, Kasznica J, Schwieterman WD, Siegel JN, Braun MM. Tuberculosis associated with infliximab, a tumor necrosis factor alpha-neutralizing agent. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1098-1104. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Franks ME, Macpherson GR, Figg WD. Thalidomide. Lancet. 2004;363:1802-1811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 447] [Cited by in RCA: 453] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sampaio EP, Sarno EN, Galilly R, Cohn ZA, Kaplan G. Thalidomide selectively inhibits tumor necrosis factor alpha production by stimulated human monocytes. J Exp Med. 1991;173:699-703. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Ehrenpreis ED, Kane SV, Cohen LB, Cohen RD, Hanauer SB. Thalidomide therapy for patients with refractory Crohn's disease: an open-label trial. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1271-1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Vasiliauskas EA, Kam LY, Abreu-Martin MT, Hassard PV, Papadakis KA, Yang H, Zeldis JB, Targan SR. An open-label pilot study of low-dose thalidomide in chronically active, steroid-dependent Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1278-1287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Haslett PA, Corral LG, Albert M, Kaplan G. Thalidomide costimulates primary human T lymphocytes, preferentially inducing proliferation, cytokine production, and cytotoxic responses in the CD8+ subset. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1885-1892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 426] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fu LM, Fu-Liu CS. Thalidomide and tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6:569-572. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Buonsenso D, Serranti D, Valentini P. Management of central nervous system tuberculosis in children: light and shade. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2010;14:845-853. [PubMed] |

| 12. | van Deventer SJ. Small therapeutic molecules for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2002;50 Suppl 3:III47-III53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Corral LG, Kaplan G. Immunomodulation by thalidomide and thalidomide analogues. Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58 Suppl 1:I107-I113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wettstein AR, Meagher AP. Thalidomide in Crohn's disease. Lancet. 1997;350:1445-1446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bariol C, Meagher AP, Vickers CR, Byrnes DJ, Edwards PD, Hing M, Wettstein AR, Field A. Early studies on the safety and efficacy of thalidomide for symptomatic inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:135-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bauditz J, Wedel S, Lochs H. Thalidomide reduces tumour necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 12 production in patients with chronic active Crohn's disease. Gut. 2002;50:196-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Keifer JA, Guttridge DC, Ashburner BP, Baldwin AS. Inhibition of NF-kappa B activity by thalidomide through suppression of IkappaB kinase activity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22382-22387. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Korzenik JR. Crohn's disease: future anti-tumor necrosis factor therapies beyond infliximab. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2004;33:285-301, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bousvaros A, Mueller B. Thalidomide in gastrointestinal disorders. Drugs. 2001;61:777-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kane S, Stone LJ, Ehrenpreis E. Thalidomide as "salvage" therapy for patients with delayed hypersensitivity response to infliximab: a case series. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:149-150. [PubMed] |