Published online Nov 21, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i43.5457

Revised: September 13, 2010

Accepted: September 20, 2010

Published online: November 21, 2010

AIM: To clarify the incidence of congenital hemolytic anemias (CHA) in young cholelithiasis patients and to determine a possible screening test based on the results.

METHODS: Young cholelithiasis patients (< 35 years) were invited to our outpatient clinic. Participants were asked for comorbidities and family history. The number of gallstones were recorded. Blood samples were obtained to perform a complete blood count, standard Wright-Giemsa staining, reticulocyte count, hemoglobin (Hb) electrophoresis, serum lactate dehydrogenase and bilirubin levels, and lipid profile.

RESULTS: Of 3226 cholecystectomy patients, 199 were under 35 years, and 190 with no diagnosis of CHA were invited to take part in the study. Fifty three patients consented to the study. The median age was 29 years (range, 17-35 years), 5 were male and 48 were female. Twelve patients (22.6%) were diagnosed as thalassemia trait and/or ıron-deficiency anemia. Hb levels were significantly lower (P = 0.046), and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and hematocrit levels were slightly lower (P = 0.072 and 0.082, respectively) than normal. There was also a significantly lower number of gallstones with the diagnosis (P = 0.007).

CONCLUSION: In endemic regions, for young cholelithiasis patients (age under 35) with 2-5 gallstones, the clinician/surgeon should pay attention to MCV and Hb levels as indicative of CHA.

- Citation: Ezer A, Torer N, Nursal TZ, Kizilkilic E, Caliskan K, Colakoglu T, Moray G. Incidence of congenital hemolytic anemias in young cholelithiasis patients. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(43): 5457-5461

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i43/5457.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i43.5457

Congenital hemolytic anemias (CHA), especially thalassemia and sickle cell anemia (SCA), are endemic in southern Turkey: the prevalence of the β-thalassemia trait is reported to be 1.84%-2.3% and the prevalence of sickle hemoglobin (Hb) is 4.6%[1,2]. Symptomatic exacerbation of severe anemia can be easily diagnosed. Preventive measures and treatment of complications are well known by the hematologists. However, the thalassemia trait and SCA trait patients rarely present with clinical symptoms, and minor hematological findings may be missed in routine clinical practice.

One of the frequent comorbidities of CHA is gallbladder stones. Chronic hemolysis causes increased bilirubin excretion and gallstone formation[3-5]. The most common types of gallstones associated with CHA are pigment gallstones. Even in cholesterol stones, a bilirubin nidus has been documented[6]. Thus, increased bilirubin acts a trigger in the formation of gallstones regardless of stone type[7]. Eighty percent of SCA and β-thalassemia major patients and more than 40% of spherocytosis patients have cholelithiasis detected at a young age, i.e. younger than 30 years[8]. Cholelithiasis would probably be the first clinical finding for these patients, particularly in hereditary spherocytosis or other rare congenital erythrocyte membrane defect patients.

We recognize that there is a distinct number of young patients with cholelithiasis in our region. Therefore, we aimed to clarify the incidence of known and unknown CHA in young cholelithiasis patients in our region. Our secondary aim was to determine a possible screening test based on the results.

The study was approved by our university’s research committee and ethics committee (KA 07/90). Between 1998 and 2007, 3226 cholelithiasis patients were treated in our hospital. Of these, 199 (6.1%) were younger than 35 years. Their files were analyzed retrospectively. Patients with known CHA were excluded. The rest of the patients were contacted by telephone and asked if they had any known hematological disease. Thereafter they were informed of the study and were invited to the outpatient clinic. Written informed consent of all participants was obtained at the clinic visit. Participants were asked to fill in a short inquiry form, which included height, weight, comorbidities, family history of any hematological disease, medications, and number of childbirths and oral contraceptive use for females. The number of gallstones had also been recorded from the preoperative medical records. Blood samples were then obtained for analysis: complete blood count, standard Wright-Giemsa staining, reticulocyte count, high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), Hb electrophoresis, serum lactate dehydrogenase and bilirubin levels, and lipid profile.

All parameters of all patients were evaluated by the same hematologist (EK) to determine if there was any diagnosis or suspicion of CHA.

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 11 for Windows. In order to analyze categorical variables the chi-square test was used. The Student t test and its nonparametric counterpart, the Mann Whitney U test, were used for continuous variables. The receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve for the studied variables and diseased patients was also obtained for sensitivity analysis.

Nine of 199 cholelithiasis patients (4.52%) had a previous diagnosis of SCA. The rest of the 190 patients were invited to the hospital and 53 patients (27.9%) consented to the study. The median age of these 53 patients was 29 years (range, 17-35 years), with 5 males and 48 females.

Hematological evaluation of all parameters revealed that there was no patient with SCA or β-thalassemia. However, 12 patients (22.6%) were diagnosed with suspected thalassemia trait and/or ıron-deficiency anemia (IDA).

The mean values of the studied parameters for suspected patients and the patients with normal hematologic findings are shown in Table 1. Hb levels were significantly lower in suspected patients compared to normal (P = 0.046). There was also a trend for lower mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and hematocrit (Hct) in suspected patients (P = 0.072 and 0.082, respectively). There was no significant difference for the other parameters between the groups (Table 1).

| Variables | Normal | Suspected | P | ||

| No. patients | mean ± SD | No. patients | mean ± SD | ||

| Age (yr) | 40 | 28.8 ± 3.9 | 12 | 27.2 ± 5.0 | 0.356 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 39 | 181.5 ± 36.6 | 11 | 184.2 ± 34.1 | 0.886 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 39 | 46.8 ± 13.9 | 11 | 47.0 ± 12.5 | 0.905 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 39 | 112.6 ± 33.2 | 11 | 117.9 ± 20.82 | 0.546 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 38 | 131.2 ± 87.3 | 10 | 135.8 ± 57.2 | 0.916 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 40 | 0.62 ± 0.35 | 10 | 0.50 ± 0.22 | 0.214 |

| Indirect bilirubin (mg/dL) | 40 | 0.42 ± 0.26 | 10 | 0.37 ± 0.18 | 0.505 |

| LDH (U/L) | 39 | 135.5 ± 35.0 | 11 | 133.5 ± 21.7 | 0.836 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 38 | 13.25 ± 1.46 | 11 | 12.31 ± 1.16 | 0.046 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 38 | 39.6 ± 4.2 | 11 | 37.2 ± 3.4 | 0.082 |

| MCV (μm3) | 36 | 84.32 ± 4.37 | 11 | 80.25 ± 5.52 | 0.072 |

| Reticulocyte (%) | 36 | 1.90 ± 3.02 | 10 | 1.37 ± 0.39 | 0.312 |

| Height (cm) | 35 | 163.2 ± 6.6 | 8 | 161.7 ± 6.4 | 0.589 |

| Weight (kg) | 37 | 69.7 ± 13.4 | 10 | 72.2 ± 14.9 | 0.640 |

| Hb A1 (%) | 38 | 96.16 ± 0.57 | 11 | 96.10 ± 0.51 | 0.757 |

| Hb A2 (%) | 38 | 2.88 ± 0.35 | 11 | 2.76 ± 0.41 | 0.401 |

| Hb S (%) | 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0 | 0 ± 0 | NA |

| Hb F (%) | 3 | 1.03 ± 0.32 | 0 | 0 ± 0 | 0.360 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 33 | 25.6 ± 4.2 | 7 | 27.3 ± 5.6 | 0.472 |

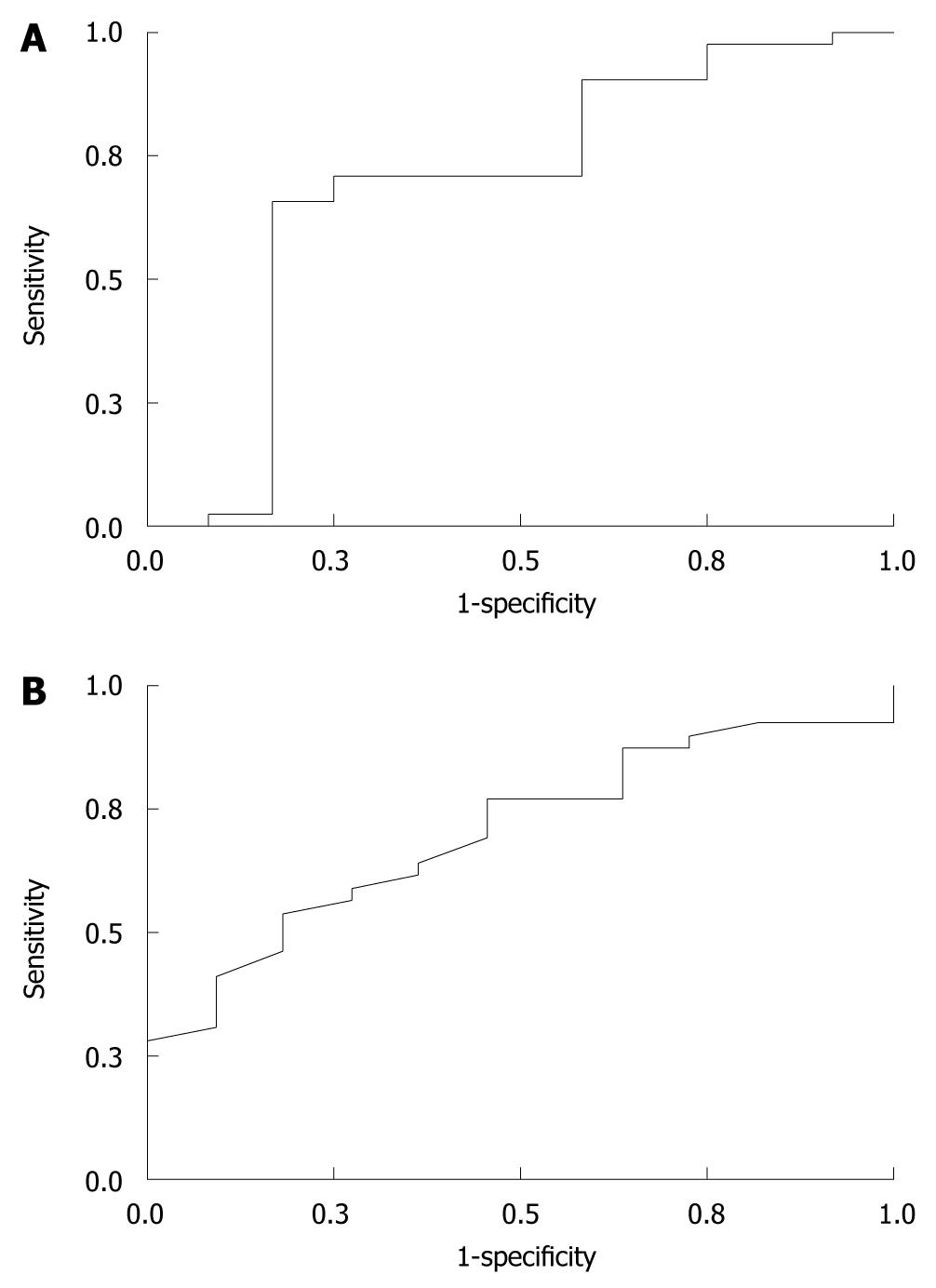

ROC curve analysis of MCV, Hb, and Hct for the diagnosis of α-thalassemia were performed separately. MCV and Hb were significantly correlated with the diagnosis of α-thalassemia. The ROC curves of MCV and Hb are shown in Figure 1. For a cutoff MCV of 82 μm3, and Hb of 120 mg/L, sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values for diagnosis are shown in Table 2.

| Variable | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value |

| MCV < 82 μm3 | 70.7 | 75.0 | 42.8 | 90.6 |

| Hb < 12 g/dL | 82.1 | 63.6 | 30.8 | 80.0 |

Obesity, gender, number of gallstones, MCV and Hb levels (lower or higher than the threshold) were grouped and analyzed to diagnose α-thalassemia. The patient distribution is shown in Table 3. There was a significant difference for the number of gallstones and MCV < 82 μm3 with the diagnosis of thalassemia trait (P = 0.004 and 0.007, respectively).

| Diagnosis | Total | P | ||

| Normal | Suspected | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| < 25 | 12 (80.0) | 3 (20.0) | 15 | 0.267 |

| 25-30 | 17 (89.5) | 2 (10.5) | 19 | |

| > 30 | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | 13 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | ||||

| < 12 | 9 (69.2) | 4 (30.8) | 13 | 0.425 |

| ≥ 12 | 32 (80.0) | 8 (20.0) | 40 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 37 (77.1) | 11 (22.9) | 48 | 0.883 |

| Male | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | 5 | |

| MCV (μm3) | ||||

| < 82 | 12 (57.1) | 9 (42.9) | 21 | 0.007 |

| ≥ 82 | 29 (90.6) | 3 (9.4) | 32 | |

| No. of gallstones | ||||

| Only one | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | 6 | 0.004 |

| 2-5 | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | 6 | |

| Multiple | 35 (85.4) | 6 (14.6) | 41 | |

| Total | 41 (77.4) | 12 (22.6) | 53 | |

The prevalence of gallbladder stone disease is 10%-20% and is increased in the elderly and female population[9,10].

Diagnosis of symptomatic SCA or β-thalassemia is not difficult. In endemic regions, it is especially important to identify carriers of these diseases. There is no cure, and the affected individuals may pass this disease to the next generation. Until gene therapy becomes a reality, the only approaches to the control of CHA are prevention and avoidance. The prevention strategies for CHA include education, carrier screening, genetic counseling, prenatal diagnosis (by amniotic fluid sampling at pregnancy) and selective termination of affected fetuses[11].

In order to reduce the birth rate of CHA in the areas of risk, efforts should be made to persuade couples to consider screening tests before the first pregnancy. For at-risk couples, details of the disorder should be explained to them so that they can make a decision in the context of their unique medical, moral and social situations[12,13]. In a previous study, premarital couples, who may be carriers for hemoglobinopathies were screened in the southern part of the Turkey by hemoglobin electrophoresis. The frequency of sickle Hb was 4.6% and β-thalassemia 2.3%. In 35 of 2113 prospective families, both partners were found to be carriers[2]. However, carrier screening by Hb electrophoresis is an expensive method for mass screening.

We found that 4.5% of young cholelithiasis patients had a known diagnosis of SCA. In this study, there was no patient with abnormal HPLC electrophoresis results suggesting congenital hemoglobinopathies. However, 22.6% of participants (young cholelithiasis patients) were found to have microcytic anemia. Although they did not present with β-thalassemia or SCA, this result suggested that these patients may have thalassemia trait and/or IDA or any other hemoglobinopathy subtypes. It is reported that in some mutations of β-thalassemia and in heterozygous α-thalassemia, Hb A2 is not elevated[14,15]. Serum iron and ferritin levels must be analyzed to differentiate between IDA and thalassemia. Patients with low serum iron levels should be initially treated with oral iron supplement and then should be re-evaluated according to the response to the treatment. Patients with normal iron levels or those with no response to replacement treatment should be assumed as hemoglobinopathy carriers. However, this is a time-consuming expensive method for differentiation.

For hematological evaluation, it is important to differentiate thalassemia and IDA. Demir et al[9] suggested that pre-keratocytes and pencil cells, as morphologic features in the Wright-Giemsa staining, are useful in differentiating IDA and thalassemia trait. However, Wright-Giemsa staining is not suitable for daily practice and needs experienced personal for evaluation. There are other indices reported for differentiation between thalassemia trait and IDA, with sensitivity of approximately 100%[16-18]. The most popular index is the ratio of MCV and red blood cell count, the so-called Mentzer Index, which can be automatically calculated with any of the hematology analyzers. This method can be implemented by hospitals and laboratories to flag positive matches and enables screening of population at risk with little to no additional cost[19,20].

Novel data in this study indicates that general surgeons who practice in CHA-endemic regions, should take care in examining young cholelithiasis patients for CHA. Evaluation of complete blood count should be mandatory for these patients. Physicians should be aware of the MCV and Hb level of the young cholelithiasis patient. A MCV < 82 μm3 and Hb < 12 g/dL should alert the physician to the possibility of thalassemia. A family history of anemia should be sought in these patients and they should consult with a hematologist. Further analysis may be necessary.

Another suggestion which may derived from this study is that young patients with less than 5 (not multiple stones or sludge) gallstones should be suspected for the hemoglobinopathies.

In conclusion, in endemic regions, for the young cholelithiasis patients (age under 35) with few gallstones, the clinician/surgeon should pay attention to MCV, Hb level and Mentzer Index.

Congenital hemolytic anemias (CHA), especially thalassemia and sickle cell anemia (SCA), are a serious problem in endemic regions. One of the frequent comorbidities of CHA is gallbladder stones. Cholelithiasis would probably be the first clinical finding for these patients.

In order to reduce the birth rate of CHA in the risk areas, prevention strategies for at-risk couples include education, carrier screening, genetic counseling, prenatal diagnosis (by amniotic fluid sampling at pregnancy) and selective termination of affected fetuses.

Premarital couples, who may be carriers for hemoglobinopathies have been screened in the southern part of the Turkey by hemoglobin electrophoresis. However, carrier screening by hemoglobin electrophoresis is an expensive method for mass screening. The most popular index is the ratio of mean corpuscular volume and red blood cell count, the Mentzer Index, which can be automatically calculated with any of the hematology analyzers. This method can be implemented by hospitals and laboratories to flag positive matches and enables screening of the population at risk with little to no additional cost.

General surgeons, who practice in CHA-endemic regions, should be careful with young cholelithiasis patients in diagnosing CHA. Evaluation of complete blood tests should be mandatory for young cholelithiasis patients.

Thalassemia and sickle cell anemia are congenital hemolytic anemias (hemoglobinopathies) which are endemic in some regions of the world.

Because the studied area is an endemic region, findings of this study are not generalizable. However the results should be important for the readers from endemic areas of the world. Low participation rate is another limitation of the study.

Peer reviewer: Leonidas G Koniaris, Professor, Department of Surgery, University of Miami, 3550 SCC, 1475 NW 12th Avenue, Miami, FL 33136, United States

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Gurbak M, Sivasli E, Coskun Y, Bozkurt AI, Ergin A. Prevalence and hematological characteristics of beta-thalassemia trait in Gaziantep urban area, Turkey. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2006;23:419-425. |

| 2. | Altay C, Yilgör E, Beksac S, Gürgey A. Premarital screening of hemoglobinopathies: a pilot study in Turkey. Hum Hered. 1996;46:112-114. |

| 3. | Duvaldestin P, Mahu JL, Metreau JM, Arondel J, Preaux AM, Berthelot P. Possible role of a defect in hepatic bilirubin glucuronidation in the initiation of cholesterol gallstones. Gut. 1980;21:650-655. |

| 4. | Borgna-Pignatti C, Rigon F, Merlo L, Chakrok R, Micciolo R, Perseu L, Galanello R. Thalassemia minor, the Gilbert mutation, and the risk of gallstones. Haematologica. 2003;88:1106-1109. |

| 5. | Currò G, Iapichino G, Lorenzini C, Palmeri R, Cucinotta E. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in children with chronic hemolytic anemia. Is the outcome related to the timing of the procedure? Surg Endosc. 2006;20:252-255. |

| 6. | Grünhage F, Lammert F. Gallstone disease. Pathogenesis of gallstones: A genetic perspective. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:997-1015. |

| 7. | Tüzmen S, Tadmouri GO, Ozer A, Baig SM, Ozçelik H, Başaran S, Başak AN. Prenatal diagnosis of beta-thalassaemia and sickle cell anaemia in Turkey. Prenat Diagn. 1996;16:252-258. |

| 8. | Sangkitporn S, Chongkitivitya N, Pathompanichratana S, Sangkitporn SK, Songkharm B, Watanapocha U, Pathtong W. Prevention of thalassemia: experiences from Samui Island. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87:204-212. |

| 9. | Demir A, Yarali N, Fisgin T, Duru F, Kara A. Most reliable indices in differentiation between thalassemia trait and iron deficiency anemia. Pediatr Int. 2002;44:612-616. |

| 10. | Kneifati-Hayek J, Fleischman W, Bernstein LH, Riccioli A, Bellevue R. A model for automated screening of thalassemia in hematology (math study). Lab Hematol. 2007;13:119-123. |

| 11. | Kejariwal D. Cholelithiasis associated with haemolytic-uraemic syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2291-2292. |

| 12. | van Assen S, Nagengast FM, van Goor H, Cools BM. [The treatment of gallstone disease in the elderly]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2003;147:146-150. |

| 13. | Ehsani MA, Shahgholi E, Rahiminejad MS, Seighali F, Rashidi A. A new index for discrimination between iron deficiency anemia and beta-thalassemia minor: results in 284 patients. Pak J Biol Sci. 2009;12:473-475. |

| 14. | Ntaios G, Chatzinikolaou A, Saouli Z, Girtovitis F, Tsapanidou M, Kaiafa G, Kontoninas Z, Nikolaidou A, Savopoulos C, Pidonia I. Discrimination indices as screening tests for beta-thalassemic trait. Ann Hematol. 2007;86:487-491. |

| 15. | Pansatiankul B, Saisorn S. A community-based thalassemia prevention and control model in northern Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2003;86 Suppl 3:S576-S582. |

| 16. | Ong KH, Tan HL, Tam LP, Hawkins RC, Kuperan P. Accuracy of serum transferrin receptor levels in the diagnosis of iron deficiency among hospital patients in a population with a high prevalence of thalassaemia trait. Int J Lab Hematol. 2008;30:487-493. |

| 17. | Polat A, Kaptanoğlu B, Aydin K, Keskin A. Evaluation of soluble transferring receptor levels in children with iron deficiency and beta thalassemia trait, and in newborns and their mothers. Turk J Pediatr. 2002;44:289-293. |

| 18. | Beyan C, Kaptan K, Ifran A. Predictive value of discrimination indices in differential diagnosis of iron deficiency anemia and beta-thalassemia trait. Eur J Haematol. 2007;78:524-526. |

| 19. | Ates F, Erkurt MA, Karincaoglu M, Aladag M, Aydogdu I. Prevalence of gallstones in patients with chronic myelocytic leukemia. Med Princ Pract. 2009;18:175-179. |

| 20. | Vicari P, Gil MV, Cavalheiro Rde C, Figueiredo MS. Multiple primary choledocholithiasis in sickle cell disease. Intern Med. 2008;47:2169-2170. |