Published online Jun 28, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i24.3083

Revised: February 7, 2010

Accepted: February 14, 2010

Published online: June 28, 2010

Biliary obstructions can lead to infections of the biliary system, particularly in patients with occluded biliary stents. Fungal organisms are frequently found in biliary aspirates of patients who have been on antibiotics and have stents; however, fungal masses, or “balls”, that fully obstruct the biliary system are uncommon and exceedingly difficult to eradicate. We present 4 cases of obstructing fungal cholangitis in patients who had metal biliary stents placed for pancreatic malignancies, and subsequently required aggressive antifungal administration along with endoscopic and radiologic interventions. This report also reviews approaches previously undertaken to manage severe obstructing fungal cholangitis.

- Citation: Story B, Gluck M. Obstructing fungal cholangitis complicating metal biliary stent placement in pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(24): 3083-3086

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i24/3083.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i24.3083

Obstructing lesions of the biliary tree include benign and malignant strictures, bile duct stones, stenotic sphincters, and obstructed endoprostheses. Obstructions can lead to infections of the biliary system, particularly in patients with occluded biliary stents. Fungal organisms are frequently found in biliary aspirates of patients who have been on antibiotics and have stents; however, fungal masses, or “balls”, that fully obstruct the biliary system are uncommon and exceedingly difficult to eradicate[1-3]. We present 4 cases of obstructing fungal cholangitis in patients who had metal biliary stents placed for pancreatic malignancies and subsequently required aggressive endoscopic and radiologic interventions.

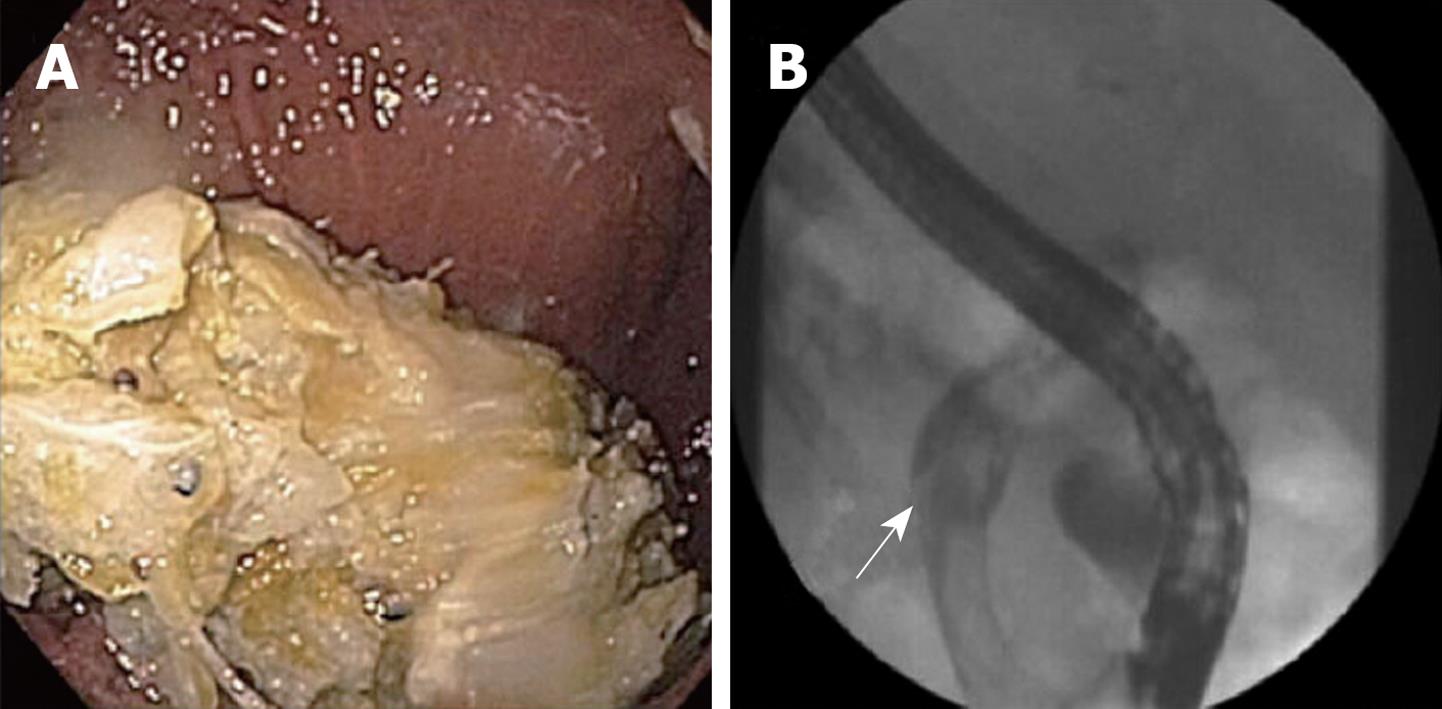

A 48-year-old male with locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer on gemcitabine and docetaxel chemotherapy, presented to our institution with fevers, rigors, jaundice, and epigastric pain 7 d after placement of a metal biliary stent at another institution. Antibiotics were started and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) showed multiple large filling defects resembling stones (Figure 1). The bile duct was cleared of all defects and the biliary stent was exchanged for a new longer metal biliary stent. Biliary aspirates grew Candida albicans. Despite starting 200 mg daily intravenous (iv) fluconazole, the biliary tree rapidly reoccluded within 3 d with large fungal balls. A repeat ERCP in which a plastic endoprosthesis was placed also occluded within 5 d with large fungal balls. A percutaneous transhepatic biliary drain (PTBD) was placed and twice daily 100 mg fluconazole flushes were initiated through the drain. The IV fluconazole was switched to 50 mg daily iv caspofungin, and this antifungal combination resulted in no further obstructions. The patient was discharged home on 200 mg/d oral fluconazole and twice daily 100 mg fluconazole flushes to be continued indefinitely. At 2 mo, repeat biliary cultures through the PTBD identified fluconazole-resistant Candida, prompting the patient’s oral regimen to be switched to 200 mg twice daily oral voriconazole. The remainder of the patient’s clinical course required occasional PTBD catheter exchanges, daily oral voriconazole, and daily intrabiliary flushing of fluconazole until he died 5 mo later secondary to his advanced pancreatic cancer.

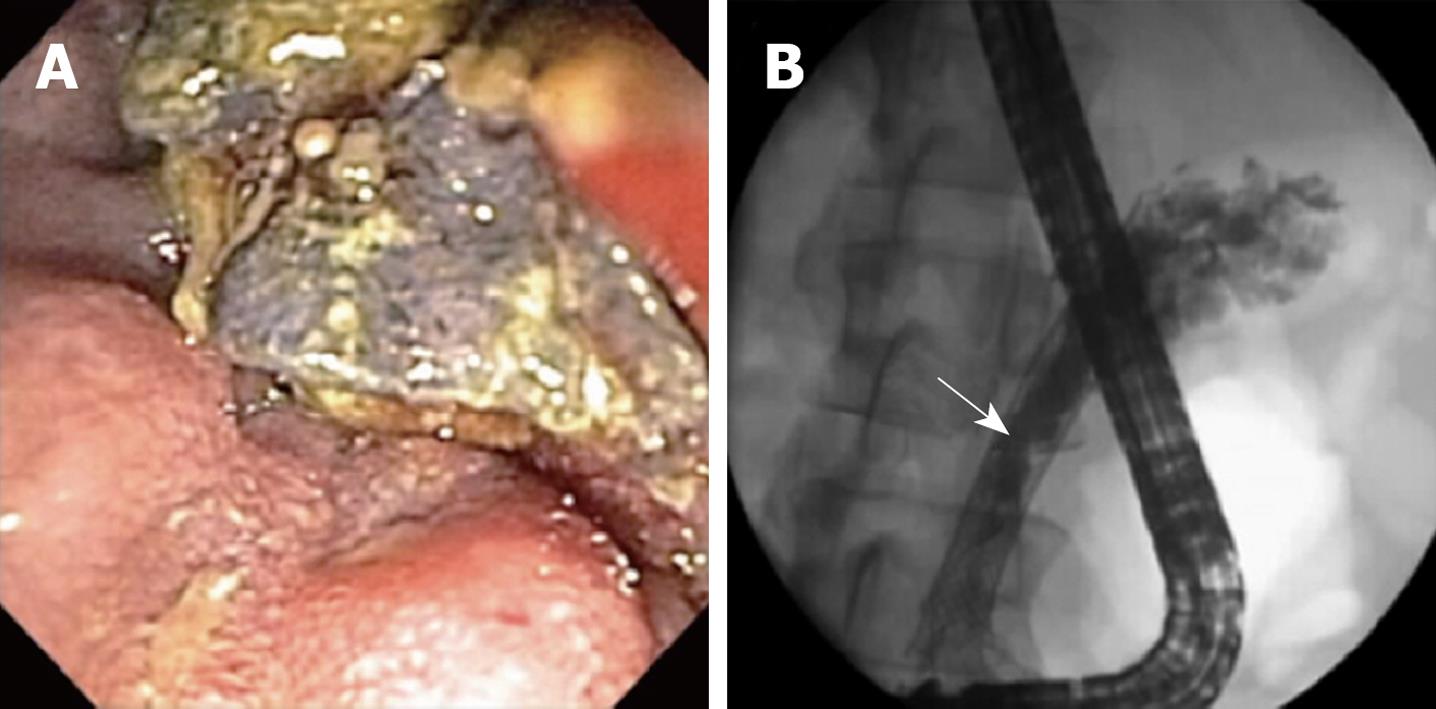

A 66-year-old female with metastatic pancreatic cancer on gemcitabine chemotherapy underwent metal biliary stent placement and percutaneous cholecystostomy tube placement for obstructive jaundice and acute cholecystitis. Her symptoms improved and 3 mo later, the gallbladder was removed. Shortly after surgery, she was readmitted for fevers, chills, and recurrent jaundice. Antibiotics for presumptive bacterial cholangitis were started and an ERCP was performed revealing caked debris on the proximal edge of her metal biliary stent and multiple soft filling defects within the common hepatic duct (Figure 2). Biliary aspirates grew Candida glabrata and Candida albicans. Despite clearing the duct of all debris and starting 200 mg twice daily oral voriconazole and 100 mg twice daily fluconazole flushes through the cholecystostomy tube, her biliary tree rapidly reoccluded in 10 d with large fungal balls. A nasobiliary drain was then placed to further facilitate fluconazole flushing into the biliary system. Eradication was finally achieved with daily oral voriconazole and daily fluconazole flushing through both the cholecystostomy tube and the nasobiliary tube. On this regimen indefinitely, the patient remained clear of further obstructions and died from her advanced pancreatic cancer 8 mo later.

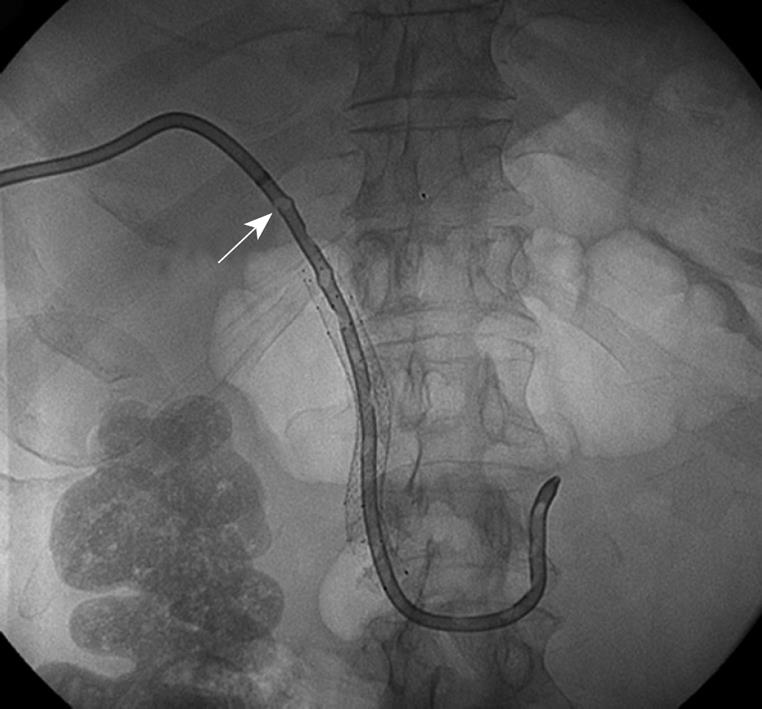

A 56-year-old male with a Merkel cell lymphoma of his leg and a large metastasis to the pancreatic head, presented to our institution with increasing fevers, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and jaundice. He had been undergoing chemotherapy with irinotecan and carboplatin, and had required duodenal stent placement for tumor overgrowth as well as PTBD and percutaneous metal biliary stent placement 7 mo previously for biliary obstruction. At the time of admission, empiric antibiotic therapy was initiated for presumptive bacterial cholangitis, and an upper endoscopy was performed revealing gastric outlet obstruction with tumor overgrowth of the duodenal stent. A new duodenal stent was placed but the biliary stent could not be visualized, requiring repeat PTBD placement. A PTBD tube check 5 d later revealed multiple soft filling defects within the PTBD catheter consistent with fungal balls (Figure 3). The PTBD catheter was exchanged and after biliary aspirates grew Candida spp, 400 mg/d oral fluconazole and 100 mg fluconazole flushes twice daily were initiated through the new PTBD catheter. However, after fluconazole-resistant Candida glabrata and Candida albicans were isolated from culture, antifungals were switched to 50 mg iv caspofungin once daily and 100 mg amphotericin B flushes once daily through the PTBD catheter. The patient was subsequently discharged from the hospital on a 3-wk course of this antifungal regimen. One month after completion of antifungal therapy, there was no further recurrence of biliary obstruction.

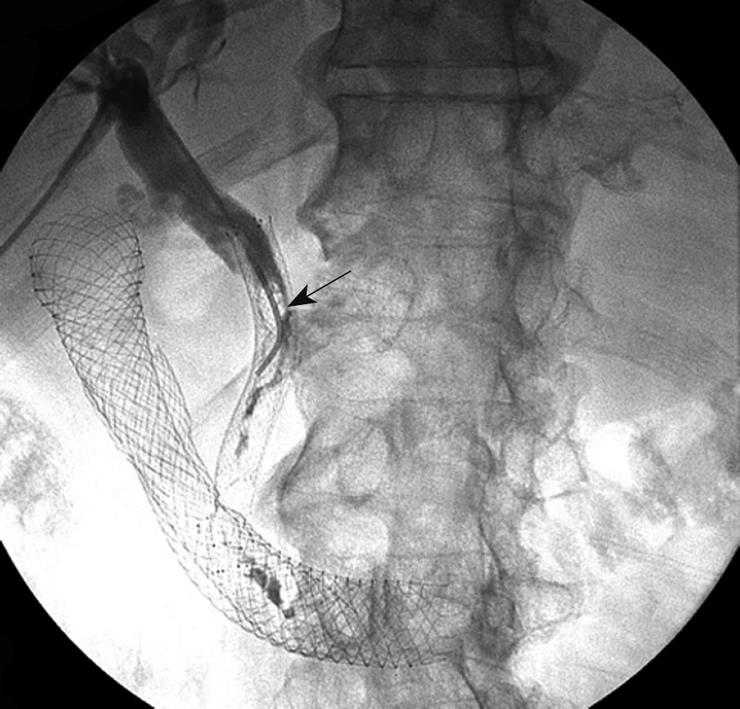

A 64-year-old male with metastatic pancreatic cancer on gemcitabine and docetaxel chemotherapy, with an indwelling metal biliary stent in place, presented to an outside facility with biliary obstruction and bacterial cholangitis. Symptoms resolved after a PTBD was placed and antibiotics were administered. However, 2 wk later, the patient re-presented to our institution with recurrent fevers and jaundice. Empiric antibiotic therapy was again initiated for presumptive bacterial cholangitis. Cholangiography performed during ERCP demonstrated obstruction due to migration of the metal biliary stent, tumor overgrowth and multiple soft filling defects consistent with fungal balls. Exchange of the PTBD catheter allowed for external drainage of biliary debris, and the aspirate grew Candida albicans in culture. Intravenous fluconazole 200 mg/d was initiated for antifungal coverage. Over the next several days, biliary obstruction persisted due to stent malpositioning, which ultimately was relieved by severing the patient’s migrated metal biliary stent. Despite these measures, within 5 d of PTBD catheter exchange and trimming of the metal biliary stent, the patient’s bile duct reobstructed with fungal balls visualized on repeat tube check (Figure 4). The PTBD catheter was exchanged and the patient was initiated on an indefinite regimen of 200 mg oral voriconazole daily and 100 mg fluconazole flushes through the PTBD catheter twice daily. Two weeks later, the patient had no further evidence of obstruction.

The patients described in this case report highlight the difficulties in treatment of obstructing fungal cholangitis following the placement of metal biliary stents. Clinical improvement was not seen with endoscopic maneuvers alone or in combination with initial systemic antifungals. Ultimately, infection control was only achieved after flushing antifungals through percutaneous intrabiliary or nasobiliary drains and escalating systemic antifungal therapy from fluconazole to voriconazole or caspofungin. All patients remained free of Candida infection following optimization of their antifungal regimens.

While the presence of biliary stents likely played a role in the development of fungal cholangitis in our case report, there are several other factors that can contribute to the development of fungal infections. These include immunosuppression secondary to chemotherapy agents, malignant hematologic disease, broad-spectrum antibiotic administration, corticosteroid therapy, diabetes mellitus, improper sterilization of endoscopes or prostheses, previous surgery, or trauma[1-6]. The patients in our case study demonstrated a number of these risk factors; all were treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, all were immunocompromised secondary to systemic chemotherapy for their pancreatic malignancies, and all had been given intermittent corticosteroids for chemotherapy administration.

The data regarding optimal treatment strategies for management of obstructing fungal masses is limited. To our knowledge, only 13 cases of obstructing fungal cholangitis have been described in the literature, the majority of which underwent systemic and intrabiliary infusion of antifungals. Several studies support our treatment approach of initiating therapy with fluconazole, given its favorable efficacy toward Candida albicans and relatively few side effects[4,6]. The literature further supports the use of escalation of therapy to voriconazole or caspofungin[6] for infection control. Other case studies, prior to the availability of voriconazole, utilized amphotericin B or liposomal amphotericin[5-8]. While the use of systemic amphotericin has been shown to have numerous complications, several case reports demonstrated that local intrabiliary infusion could be effective[5,6,8]. Interestingly, 2 case studies[1,4] reported no further antifungal administration was necessary following bile duct drainage of fungal balls for complete fungal eradication. Further details are shown in Table 1.

| Author | Presentation | Treatment | Fungal eradication |

| Marcucci et al[1], 1978 | Abdominal (Abd) pain, jaundice | Surgical removal of fungal balls/drainage. No chemotherapy | Yes |

| Magnussen et al[11], 1979 | Acute myelogenous leukemia, elevated liver function tests (LFTs) | Surgical removal of fungal balls, amphotericin B | Yes |

| Carstensen et al[2], 1986 | Abd pain, jaundice | Surgical removal, T-tube drainage, antifungals | Yes |

| Irani et al[7], 1986 | Jaundice, s/p thoracic abdominal aortic aneurysm repair | Amphotericin B | No, died of cerebral infarct |

| Ho et al[3], 1988 | Sickle cell disease, abd pain, jaundice, s/p cholecystecomy | Surgical removal, intrabiliary amphotericin B | Yes |

| Wig et al[4], 1998 | Abd pain, jaundice | Nasobiliary drainage, ex-lap with T-tube placement; no chemotherapy | Yes |

| Reeves et al[8], 2000 | Abd pain, jaundice | Endoscopic debridement, intrabiliary amphotericin B, oral fluconazole | Yes |

| Domagk et al[5], 2001 and Domagk et al[6], 2006 | Elevated LFTs, dilated bile ducts | Sphincterotomy, debridement, systemic/intrabiliary antifungals | Yes |

| Dilated bile ducts | Sphincterotomy, debridement, systemic/intrabiliary antifungals | Yes | |

| Abd pain, jaundice | Sphincterotomy, nasobiliary drainage, systemic/intrabiliary antifungals | Yes | |

| Abd pain, jaundice | Sphincterotomy, debridement, nasobiliary drainage, systemic/intrabiliary antifungals | Yes | |

| Elevated LFTs | Sphincterotomy, debridement, nasobiliary drainage, systemic/intrabiliary antifungals | Yes | |

| Elevated LFTs | Sphincterotomy, debridement, nasobiliary drainage, systemic/intrabiliary antifungals | No | |

| Abd pain, jaundice | Sphincterotomy, debridement, nasobiliary drainage, systemic/intrabiliary antifungals | No |

Fungal biliary aspirates are frequently positive in patients who have stents and have been on antibiotics[9,10]. However, it is uncommon to find completely obstructed bile ducts caused by large fungal “balls,” implying that growth of the organism was rapid in a previously contaminated system due to foreign bodies and antibiotics. The pathogenesis of common bile duct fungal balls is largely unknown; however, 2 possible explanations exist. Firstly, formation of microabscesses in the liver parenchyma from fungal sepsis may allow movement of fungal organisms into the extra-hepatic biliary system[11]. A second hypothesis involves direct invasion of Candida into the common bile duct from the duodenum, with “fungal ball” formation resulting from rapid growth of a superficial mat of fungal mycelia on the bile duct surface[7,11]. Fragmented pieces of fungi and mucoid debris become molded to bile duct walls. Subsequent invasion and proliferation of fungal hyphae may be further aided by the presence of metal biliary stents, acting as a scaffold for infection[7,11].

The treatment strategies described herein address both of the above hypotheses. Systemic antifungal administration targets fungal sepsis, preventing further aggregation of fungal organisms. The direct invasion hypothesis is supported by the fact that fungal balls are easily swept out of the biliary system by endoscopic maneuvers. As such, treating the fungal conglomerates directly by flushing antifungal medications through percutaneous or nasobiliary drains may be a more effective treatment strategy than systemic hematologic dissemination of antifungal therapies[8]. The results seen in the 4 cases described in this report further support this idea. While it seems intuitive that intrabiliary antifungal concentrations would be higher with direct flushing than with systemic antifungal administration, both approaches seem to be required to prevent reocclusion of the biliary system. Further studies are needed to expand on these findings.

Peer reviewers: Pauli Antero Puolakkainen, MD, PhD, Professor of Surgery, Chairman, Department of Surgery, Turku University Hospital, Turku, Finland; Jon Arne Søreide, Professor, MD, PhD, FACS, Department of Surgery, Stavanger University Hospital, N-4068 Stavanger, Norway; Ashok Kumar, MD, Department of Surgical Gastroenterology, Sanjay Gandhi Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, 226014, India

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Marcucci RA, Whitely H, Armstrong D. Common bile duct obstruction secondary to infection with Candida. J Clin Microbiol. 1978;7:490-492. |

| 2. | Carstensen H, Nilsson KO, Nettelblad SC, Cederlund CG, Hildell J. Common bile duct obstruction due to an intraluminal mass of candidiasis in a previously healthy child. Pediatrics. 1986;77:858-861. |

| 3. | Ho F, Snape WJ Jr, Venegas R, Lechago J, Klein S. Choledochal fungal ball. An unusual cause of biliary obstruction. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:1030-1034. |

| 4. | Wig JD, Singh K, Chawla YK, Vaiphei K. Cholangitis due to candidiasis of the extra-hepatic biliary tract. HPB Surg. 1998;11:51-54. |

| 5. | Domagk D, Bisping G, Poremba C, Fegeler W, Domschke W, Menzel J. Common bile duct obstruction due to candidiasis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:444-446. |

| 6. | Domagk D, Fegeler W, Conrad B, Menzel J, Domschke W, Kucharzik T. Biliary tract candidiasis: diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in a case series. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2530-2536. |

| 7. | Irani M, Truong LD. Candidiasis of the extrahepatic biliary tract. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1986;110:1087-1090. |

| 8. | Reeves AR, Johnson MS, Stine S. Percutaneous diagnosis and treatment of biliary candidiasis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11:107-109. |

| 9. | Dowidar N, Kolmos HJ, Lyon H, Matzen P. Clogging of biliary endoprostheses. A morphologic and bacteriologic study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:1137-1144. |

| 10. | Di Rosa R, Basoli A, Donelli G, Penni A, Salvatori FM, Fiocca F, Baldassarri L. A microbiological and morphological study of blocked biliary stents. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 1999;11:84-88. |

| 11. | Magnussen CR, Olson JP, Ona FV, Graziani AJ. Candida fungus balls in the common bile duct. Unusual manifestation of disseminated candidiasis. Arch Intern Med. 1979;139:821-822. |