Published online Jul 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3210

Revised: June 9, 2009

Accepted: June 16, 2009

Published online: July 14, 2009

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) still remains a considerable challenge for surgeons. Surgery, including liver transplantation, is the most important therapeutic approach for patients with this disease. HCC is frequently diagnosed at advanced stages and has a poor prognosis with a high mortality rate even when surgical resection has been considered potentially curative. This brief report summarizes the current status of the management of this malignancy and includes a short description of new pharmacological approaches in HCC treatment.

- Citation: Rampone B, Schiavone B, Martino A, Viviano C, Confuorto G. Current management strategy of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(26): 3210-3216

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i26/3210.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3210

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related death and accounts for as many as 500 000 deaths annually being a considerable challenge for surgeons[1]. The incidence of HCC varies by geographic location from a relatively rare tumour, like those found in North America and Europe, to a very common and highly malignant tumour as occurs in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. HCC has been found to account for 80% of all primary liver cancers, being the fifth most common cancer worldwide[12]. Most patients with HCC also suffer from coexisting cirrhosis, which is the major clinical risk factor for hepatic cancer and is correlated to hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection[3]. However, cirrhosis from non-viral causes such as alcoholism, hemochromatosis and primary biliary cirrhosis are also associated with an elevated risk of HCC. Furthermore, concomitant risk factors such as HCV infection in addition to alcoholism, tobacco use, diabetes or obesity increase the relative risk of HCC development, as numerous studies in humans and animal models have shown[4–10]. The incidence of HCC varies by geographic area worldwide. Research has shown that Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa have an incidence rate of HCC that ranges from 150 to 500 per 100 000 population, primarily because of the endemic nature of hepatitis B and C in those regions[11–13].

HCV accounts for almost 90% of all cases of HCC in Japan, and in China, hepatitis B infection is diagnosed in about 80% of patients with HCC[12–14]. In Europe and North America, however, despite a significantly lower incidence rate of 3 to 4 per 100 000 population, a distinct increase in cases of HCC has been reported as a result of intravenous drug use, unsafe sexual practices, and other causes[15–17]. Because of a lack of effective HCV vaccination, underlying HCV infection is largely responsible for that increase. As a result of the interval between the onset of infection and the development of liver cirrhosis, the incidence of HCV-related HCC will continue to increase over the next few years[18]. In contrast to Asian populations, the percentage of Western patients with HCC but without underlying cirrhosis is considerable, and the development of HCC in cirrhotic individuals in the West is associated with a wider spectrum of underlying diseases. In the West, the percentage of virally engendered cirrhosis is lower than that in Asian regions, but alcohol-toxic or cryptogenic hepatic damage is observed more frequently in Western countries[14]. Thus, the etiologic pattern of HCC in Western regions of low risk for that disease differs appreciably from that in Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Surgery, including liver transplantation (LT), still remains the most important therapeutic approach for patients with HCC. Over the past few decades, considerable progress has been made in the diagnosis and surgical treatment of HCC. In fact, tumors are now often identified at an early stage[1920], surgery is safer with an acceptable overall mortality rate (in cirrhotic patients < 5%), being characterized by a good long-term survival[2122] and results of LT have steadily improved because of careful patient selection[23].

However, HCC is still associated with a high rate of mortality and prognosis of this tumour is poor even when treatment has been considered potentially curative[2425].

This brief report summarizes the current status of the management of this disease and includes a short description of a new pharmacological approach in HCC treatment.

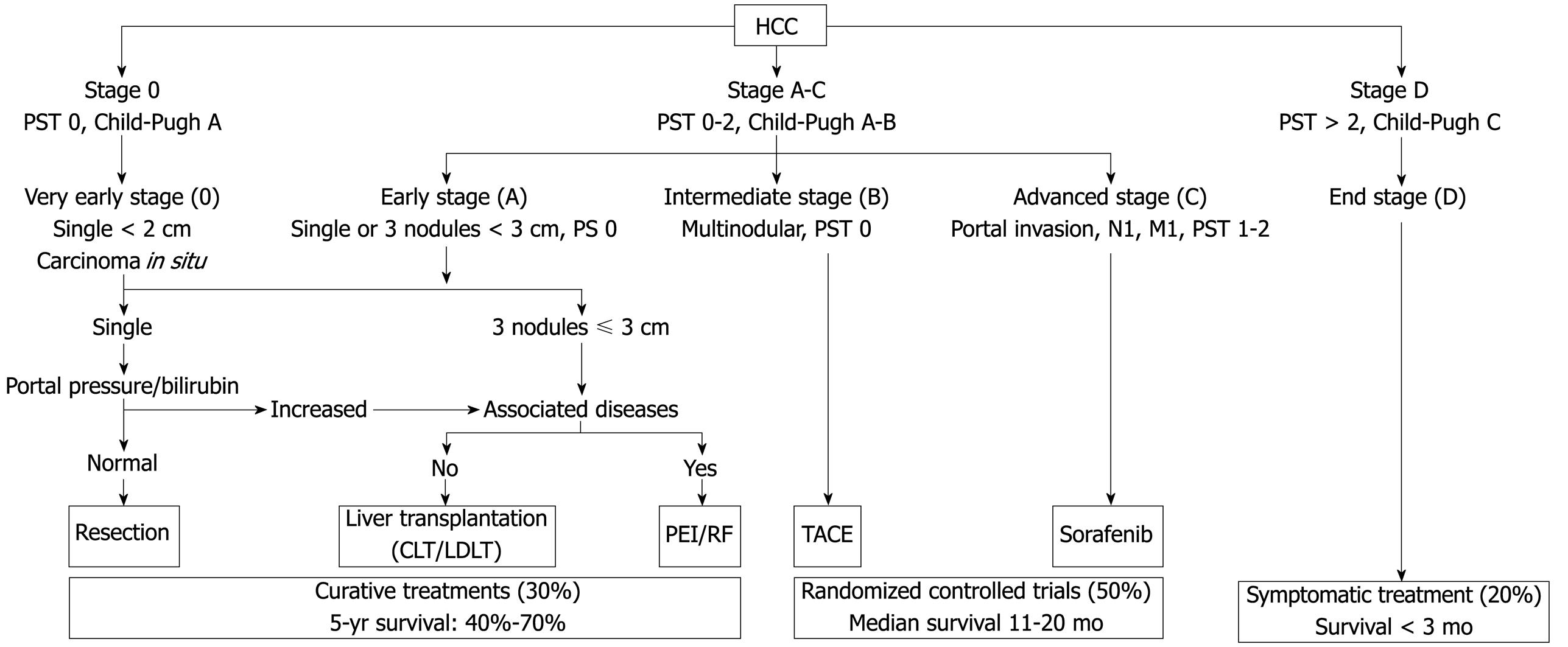

Various classification systems are available for HCC. The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) classification has emerged during recent years as the standard classification that is used for trial design and clinical management of patients with HCC[2627]. This classification has been approved by EASL and the AASLD[2428] and has subsequently been corroborated in clinical studies[2930]. The BCLC staging system was constructed on the basis of the results obtained in the setting of several cohort studies and randomized controlled trials by the Barcelona group.

The main prognostic factors of this staging system are related to tumour status (defined by the number and size of nodules, the presence or absence of vascular invasion, and the presence or absence of extrahepatic spread), liver function (defined by the Child-Pugh score system, serum bilirubin and albumin levels, and portal hypertension), and general health status [defined by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), classification and presence of symptoms]. On the other hand, aetiology is not an independent prognostic factor. The BCLC classification links stage stratification with a recommended treatment strategy and defines standard of care for each tumour stage (Figure 1).

Patients with very early HCC (stage 0) are optimal candidates for resection. Patients with early HCC (stage A) should be considered for radical therapy [resection, LT, or local ablation via percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) or radiofrequency (RF) ablation]. Patients with intermediate HCC (stage B) have been found to benefit from transarterial chemoembolization (TACE). Patients with advanced HCC, defined as the presence of macroscopic vascular invasion, extrahepatic spread, or cancer-related symptoms (ECOG performance status 1 or 2) (stage C), have recently been found to benefit from Sorafenib treatment[3132]. Patients with end-stage disease (stage D) will receive symptomatic treatment.

Treatment strategy will transition from one stage to another on treatment failure or contraindications for the procedures.

Pre-treatment imaging studies such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, either with or without angiography, can be used to match patients with their most appropriate treatment. Positron emission tomography is also useful in the identification of extrahepatic metastases which considerably influence clinical decision-making. These types of studies aid in detecting intrahepatic and extrahepatic disease as well as vascular invasion. Knowledge about the relation of the tumour to regional anatomic structures such as large vessels is crucial because it provides valuable information about resectability. Furthermore, volumetric studies can be used to define the residual parenchyma exactly. The determination of hepatic reserve is also significant when resection is considered. The healthy liver has a great capacity for regeneration and adjusts to the metabolic requirements of the host after liver resection due to hypertrophy of the residual liver. Partial hepatectomy usually ensures a safety margin of at least one centimeter and is associated with an operative mortality rate of less than 5%[3334]. For patients with inadequate or borderline remnant parenchyma, hypertrophy of the prospective liver remnant can be induced by preoperative portal vein embolization[35]. However, the use of portal vein embolization to induce compensatory hypertrophy of healthy liver before major resection is controversial. Uncontrolled tumour progression as a result of the proliferation of malignant cells stimulated by this method and the risk of variceal bleeding resulting from acute portal hypertension should be carefully considered and for that reason this procedure raises some concerns[36]. In certain circumstances, an unfavourable location of the tumour and involvement of the confluence of the three hepatic veins and either the caval vein or the retrohepatic caval vein can render resection by conventional techniques impossible. In these rare cases, special techniques such as in situ or ante situm resection can be used[37].

The overall long-term results after resection are favourable. However, only 20% to 30% of patients with HCC are eligible for resection because of advanced or multifocal disease or inadequate functional hepatic reserve[38]. In patients with solitary lesions of less than 5 cm, no vascular invasion, and a negative surgical margin of at least 1 cm, the 5-year survival rate after resection has been reported to be greater than 70%[39]. In a series consisting of 68 patients with HCC and non-cirrhotic liver, an overall 5-year survival rate of 40% was achieved even when extensive resection had been performed[40]. Similar results were observed in a large series in which patients with HCC and non-cirrhotic liver demonstrated a survival rate of 58% after 3 years and 42% after 5 years[41].

Despite earlier detection, safer surgical procedures and more aggressive treatment of HCC, recurrence, as a result of multicentric carcinogenesis or intrahepatic metastases from the primary tumour may occur. In selected patients, repeat resection provides good long-term benefits and is an option for those with solitary peripheral tumors that can be treated with segmental or atypical resection. In patients with adequate functional reserve capacity and no extrahepatic tumour growth, the 5-year survival rate after repeat resection has been reported to be as high as 86%[42].

LT is one of the best treatment approaches for HCC in patients who fulfil the selection criteria (solitary tumors of less than 5 cm and up to three tumour nodules, each of which is smaller than 3 cm)[23]. First, it removes the tumour with the widest margin together with any intrahepatic metastasis. Second, it cures the underlying cirrhosis that is responsible for both hepatic decompensation and metachronous tumour after partial hepatectomy. Finally, it allows the histologic examination of the entire liver explant for the most accurate pathologic staging.

Study results have generally shown a significantly higher probability of survival in patients with incidentally discovered tumors, no vascular invasion, a negative nodal status, a tumour size of less than 5 cm, and a tumour of lower histologic grade[43–48]. The 5-year reported survival rate is around 26% after resection and 69% after transplantation in cirrhotic patients with HCC[43]. The decisive prognostic factor for patients with HCC is vascular invasion, which no system of medical imaging can accurately demonstrate at this time[49]. Therefore, the preoperative prognosis is still based on the number and size of tumour nodes demonstrated, due to the evidence that vascular invasion has been found to be correlated to tumour size and number[44]. Because of the present lack of organs available, an accurate estimation of the patient’s prognosis is important and not every patient with HCC and cirrhosis can be treated with LT. Thus the need to obtain the optimal benefit from the limited number of organs available has prompted adherence to strict selection criteria, so that only those patients with early HCC and the highest likelihood of survival after transplantation are listed to undergo that procedure (Figure 1).

Excellent 5-year post-transplant patient survival of at least 70% has been reported from many centres[5051]. In another study, excellent results were achieved in patients with solitary lesions of a maximum diameter of 6.5 cm, patients with a maximum of three lesions (the largest of which was no larger than 4.5 cm), and those who had no more than 8 cm in diameter in all tumour nodes. The 1-year and 5-year survival rates of these patients were as high as 90% and 72%, respectively[52].

Even if the selection criteria for LT to treat HCC could be expanded, the current shortage of liver grafts and the lack of data defining the new limits for LT in patients with HCC makes the attempt to expand the listing criteria a very controversial issue. As a result of expanded listing criteria, the inclusion of patients with more advanced cancer may result in a higher dropout rate that in turn leads to poor survival rates in an intent-to-treat analysis[5354].

In their recent publication, Mazzaferro and colleagues[55] developed a new prognostic model that could be used to expand the Milan criteria and help identify patients whose odds of survival could be improved by having a liver transplant. Using the “up-to-seven” criteria, where seven is the maximum number obtained by adding the size of the largest tumour (in centimeter) to the total number of tumors, the report indicates that the 5-year survival in patients without microvascular invasion was 71.2%, similar to patients who met the Milan criteria. The researchers conclude: more patients with HCC could be candidates for transplantation if the current dual (yes/no) approach to candidacy, based on the strict Milan criteria, was replaced with a more precise estimation of survival contouring individual tumour characteristics and use of the up-to-seven criteria.

Therefore, the ultimate therapeutic choice should always result from the analysis of each individual case and should be based on the experience and judgment of the transplant team and not just on the statistical results derived from the literature.

The wait for a graft to become available still presents the greatest challenge. Methods of neoadjuvant therapy (PEI, RF, TACE) may be used to provide tumour control in patients on a waiting list for LT.

Patients can reach a prognostically unfavourable stage because of tumour progression with subsequent deterioration of their clinical profile while waiting and may no longer fulfil the criteria for LT[52]. As a result, these patients should be removed from the waiting list, indeed about 50% of HCC patients who were initially candidates for LT will become ineligible for transplantation if the median waiting period exceeds 1 year[5356].

Strategies to increase the donor pool and diminish the tumour progression rate have become a priority in many centres. In the United States, the United Network for Organ Sharing proposed a new system to allocate patients on the list according to the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score[57]. This change gives priority to patients to minimize drop-out rates and has improved the access to timely liver transplant for patients with HCC[58].

Recent advances in adult living-donor liver transplantation (LDLT) may produce a drastic change in the role of transplantation surgery for HCC. This option enables patients to avoid the long waiting time before transplantation and consequently to reduce the dropout rate. The keynote of living donation in patients with HCC and cirrhosis is supported by these factors: (1) Better graft function, because each graft is obtained from a healthy person; (2) Better clinical condition of the patient at the time of transplantation; (3) Optimal organ harvest, conservation, and reduced cold ischemia time; (4) A significantly reduced waiting time.

Whether LDLT is indicated in patients with HCC that exceeds the Milan criteria remains controversial[5960]. A recent survey of transplant surgeons from North America, Europe, and Asia revealed that 41% of the respondents favoured LDLT for use in patients with HCC that exceeds the Milan criteria[61]. Patients who no longer fulfil the criteria because of tumour size or the number of tumour nodes may still retain the option of LDLT. Because a potential 5-year survival rate of around 50% in patients whose LT is justified by extended criteria has been described[53], transplantation would offer a better chance of survival than would all other therapeutic options.

However, evidence-based universal guidelines for this important issue have not been established. Primary graft failure and the risk to the donor present ethical concerns that cannot be disregarded. Donor deaths and other complications, such as insufficiency of the donor’s remaining liver (which required subsequent transplantation), have been reported[62]. Furthermore, some data also suggest the need to have a better evaluation of the donor, including liver histology[63]. The complication rate for LT in North America and Europe ranges between 9.2% and 40% for the donor, and the mortality risk in donors is still 0.3% to 0.61%[6465]. In contrast, data in Japan showed a complication rate of 12% with no perioperative deaths in living liver donors[66]. Meticulous surgical techniques and perioperative management, lean body mass in individual Japanese donors, and genetic factors were given as possible explanations for the zero transplant-related mortality rate in Japan. In general, however, morbidity after living liver donation strongly correlates with the expertise of the staff of the transplant centre. Therefore, a combination of surgical expertise and thorough, individualized medical and psychological evaluations is vital to ensure the lowest morbidity rate and best outcome, not only in the recipient, but also in the donor.

Percutaneous ablation: For patients who are not candidates for liver resection or transplantation, percutaneous ablation offers the best treatment option. However, to our knowledge, there are no randomized controlled clinical trials that have compared the results of this treatment option with those of surgical therapy for HCC, and none of the ablation techniques have been shown to offer a definitive survival advantage. The principle of ablation is based on the destruction of tumour cells by the application of chemical substances, such as ethanol, or by using RF or laser to modify the temperature in the tumour via the delivery of heat. Of all those techniques, PEI has been the most investigated[67]. In individuals who do not fit the optimal surgical profile, PEI is as effective as surgery and is associated with a 5-year survival rate as high as 72% if the accurate selection of patients is performed[6869]. The low rate of procedure-related complications and the low cost of PEI are additional advantages. The main drawback of this technique is the need for repeated injections in separate sessions and the inability to achieve complete necrosis in larger tumors. In that regard, RF ablation has been shown to be more effective in achieving complete necrosis in tumors larger than 2 cm and to require fewer treatment sessions[70]. RF ablation involves the delivery of energy created by RF waves to tumors to induce thermal damage and coagulative necrosis. Study results have shown that RF ablation is superior to PEI in terms of causing complete tumour necrosis (90% vs 80%) and in the number of required treatments (1.2 vs 4.8)[71]. However, RF ablation causes more complications such as pleural effusion, bleeding, and tumour seeding than does PEI[7172]. In addition, the effectiveness of RFA decreases as the tumour size exceeds 3 cm.

Chemoembolization: This approach can be used before liver resection to improve resectability, as a bridge to LT while awaiting organ availability, or as a palliative treatment, and it may offer patients with preserved liver function and no evidence of ascites a survival advantage[73]. Chemoembolization is based on the principle of arterial obstruction (obstruction of the hepatic artery during angiography via the use of agents such as an absorbable gelatin sponge, alcohol, etc, to induce ischemic tumour necrosis). This technique is effective because the growth of HCC depends primarily on the hepatic artery blood supply, but the healthy hepatic parenchyma has a dual blood supply (85% is supplied by the portal vein, and the remainder is supplied by the hepatic artery). The injection of a chemotherapeutic agent [usually cisplatin, doxorubicin hydrochloride (Adriamycin), or mitomycin C] before arterial obstruction (transcatheter arterial embolization) results in TACE, a method by which regionally elevated levels of these agents in the liver can be achieved while concomitant systemic toxicity is avoided. When compared with controls, patients treated with TACE exhibited a decrease in tumour size of 16% to 61% and a 1-year survival advantage as high as 82%[74–77].

A number of systemic chemotherapies have been evaluated in many clinical trials. Unfortunately, no single agent or combination of agents given systemically leads to reproducible response rates that show beneficial effect of systemic chemotherapy on survival rates[78]. Tamoxifen, octreotide, interferon, and interleukin-2 have not been shown to be effective in treating HCC in randomized controlled clinical trials[7980]. The increasing knowledge in the molecular structure of HCC as well as the introduction of molecular targeted therapies in oncology have created an encouraging trend in the management of this disease[81]. These targeted molecular therapies are aimed at growth factors and their receptors, intracellular signal transduction and cell cycle control. Recent positive results from a preliminary study of the receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, sorafenib, have been reported in the treatment of HCC[3132]. This oral multikinase inhibitor action of several kinases (VEGF, PDGF, c-kit receptor, Raf) involved in both tumour cell proliferation (tumour growth) and angiogenesis (tumour blood supply).

Novel treatment options based on an improved understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of HCC have been proposed. Nonetheless a substantial improvement in the outcomes of intermediate and advanced stage HCC is expected with the advent of these targeted therapies, used in combination with surgical or locoregional therapies.

LT still remains an important treatment approach for HCC and is a well-documented and proven treatment modality for this disease. However, early unsatisfactory results have emphasized that only a highly selected patient population would benefit from transplantation. Pretransplantation therapies and the development of novel agents to prevent progression of HCC in patients awaiting LT are needed. Promotion of organ donation is necessary, the role of new systemic therapy is now becoming a new and interesting option in the treatment of patients with HCC, but LDLT as the dominant strategy will continue to escalate.

| 1. | Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Estimating the world cancer burden: Globocan 2000. Int J Cancer. 2001;94:153-156. |

| 2. | Befeler AS, Di Bisceglie AM. Hepatocellular carcinoma: diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1609-1619. |

| 3. | Liu JH, Chen PW, Asch SM, Busuttil RW, Ko CY. Surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma: does it improve survival? Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11:298-303. |

| 4. | Fong TL, Kanel GC, Conrad A, Valinluck B, Charboneau F, Adkins RH. Clinical significance of concomitant hepatitis C infection in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 1994;19:554-557. |

| 5. | Ming L, Thorgeirsson SS, Gail MH, Lu P, Harris CC, Wang N, Shao Y, Wu Z, Liu G, Wang X. Dominant role of hepatitis B virus and cofactor role of aflatoxin in hepatocarcinogenesis in Qidong, China. Hepatology. 2002;36:1214-1220. |

| 6. | Hassan MM, Hwang LY, Hatten CJ, Swaim M, Li D, Abbruzzese JL, Beasley P, Patt YZ. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma: synergism of alcohol with viral hepatitis and diabetes mellitus. Hepatology. 2002;36:1206-1213. |

| 7. | Ohata K, Hamasaki K, Toriyama K, Matsumoto K, Saeki A, Yanagi K, Abiru S, Nakagawa Y, Shigeno M, Miyazoe S. Hepatic steatosis is a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Cancer. 2003;97:3036-3043. |

| 8. | El-Serag HB, Richardson PA, Everhart JE. The role of diabetes in hepatocellular carcinoma: a case-control study among United States Veterans. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2462-2467. |

| 9. | Davila JA, Morgan RO, Shaib Y, McGlynn KA, El-Serag HB. Diabetes increases the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: a population based case control study. Gut. 2005;54:533-539. |

| 10. | Chokshi MM, Marrero JA. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2001;17:276-280. |

| 11. | Kew MC. The development of hepatocellular cancer in humans. Cancer Surv. 1986;5:719-739. |

| 12. | Di Bisceglie AM. Hepatitis C and hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 1995;15:64-69. |

| 13. | El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis C in the United States. Hepatology. 2002;36:S74-S83. |

| 14. | Beasley RP. Hepatitis B virus. The major etiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 1988;61:1942-1956. |

| 15. | Wingo PA, Tong T, Bolden S. Cancer statistics, 1995. CA Cancer J Clin. 1995;45:8-30. |

| 16. | El-Serag HB, Mason AC. Rising incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:745-750. |

| 17. | Allen J, Venook A. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemic and treatment. Curr Oncol Rep. 2004;6:177-183. |

| 18. | Tanaka Y, Hanada K, Mizokami M, Yeo AE, Shih JW, Gojobori T, Alter HJ. Inaugural Article: A comparison of the molecular clock of hepatitis C virus in the United States and Japan predicts that hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in the United States will increase over the next two decades. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15584-15589. |

| 19. | Bolondi L, Sofia S, Siringo S, Gaiani S, Casali A, Zironi G, Piscaglia F, Gramantieri L, Zanetti M, Sherman M. Surveillance programme of cirrhotic patients for early diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a cost effectiveness analysis. Gut. 2001;48:251-259. |

| 21. | Makuuchi M, Sano K. The surgical approach to HCC: our progress and results in Japan. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:S46-S52. |

| 22. | Shimozawa N, Hanazaki K. Longterm prognosis after hepatic resection for small hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;198:356-365. |

| 23. | Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, Montalto F, Ammatuna M, Morabito A, Gennari L. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693-699. |

| 24. | Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208-1236. |

| 25. | Tang ZY. Hepatocellular carcinoma--cause, treatment and metastasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:445-454. |

| 26. | Tang ZY. Hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15 Suppl:G1-G7. |

| 27. | Llovet JM, Di Bisceglie AM, Bruix J, Kramer BS, Lencioni R, Zhu AX, Sherman M, Schwartz M, Lotze M, Talwalkar J. Design and endpoints of clinical trials in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:698-711. |

| 28. | Bruix J, Sherman M, Llovet JM, Beaugrand M, Lencioni R, Burroughs AK, Christensen E, Pagliaro L, Colombo M, Rodés J. Clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Conclusions of the Barcelona-2000 EASL conference. European Association for the Study of the Liver. J Hepatol. 2001;35:421-430. |

| 29. | Marrero JA, Fontana RJ, Barrat A, Askari F, Conjeevaram HS, Su GL, Lok AS. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of 7 staging systems in an American cohort. Hepatology. 2005;41:707-716. |

| 30. | Cillo U, Vitale A, Grigoletto F, Farinati F, Brolese A, Zanus G, Neri D, Boccagni P, Srsen N, D'Amico F. Prospective validation of the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging system. J Hepatol. 2006;44:723-731. |

| 31. | Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:378-390. |

| 32. | Llovet JM, Bruix J. Molecular targeted therapies in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2008;48:1312-1327. |

| 33. | Buell JF, Rosen S, Yoshida A, Labow D, Limsrichamrern S, Cronin DC, Bruce DS, Wen M, Michelassi F, Millis JM. Hepatic resection: effective treatment for primary and secondary tumors. Surgery. 2000;128:686-693. |

| 34. | De Carlis L, Giacomoni A, Pirotta V, Lauterio A, Slim AO, Sammartino C, Cardillo M, Forti D. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular cancer in the era of hepatic transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:887-897. |

| 35. | Vauthey JN, Chaoui A, Do KA, Bilimoria MM, Fenstermacher MJ, Charnsangavej C, Hicks M, Alsfasser G, Lauwers G, Hawkins IF. Standardized measurement of the future liver remnant prior to extended liver resection: methodology and clinical associations. Surgery. 2000;127:512-519. |

| 36. | Farges O, Belghiti J, Kianmanesh R, Regimbeau JM, Santoro R, Vilgrain V, Denys A, Sauvanet A. Portal vein embolization before right hepatectomy: prospective clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2003;237:208-217. |

| 37. | Oldhafer KJ, Lang H, Malagó M, Testa G, Broelsch CE. [Ex situ resection and resection of the in situ perfused liver: are there still indications?]. Chirurg. 2001;72:131-137. |

| 38. | Tsuzuki T, Sugioka A, Ueda M, Iida S, Kanai T, Yoshii H, Nakayasu K. Hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery. 1990;107:511-520. |

| 39. | Yamanaka N, Okamoto E, Toyosaka A, Mitunobu M, Fujihara S, Kato T, Fujimoto J, Oriyama T, Furukawa K, Kawamura E. Prognostic factors after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinomas. A univariate and multivariate analysis. Cancer. 1990;65:1104-1110. |

| 40. | Bismuth H, Chiche L, Castaing D. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinomas in noncirrhotic liver: experience with 68 liver resections. World J Surg. 1995;19:35-41. |

| 41. | Fong Y, Sun RL, Jarnagin W, Blumgart LH. An analysis of 412 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma at a Western center. Ann Surg. 1999;229:790-799; discussion 799-800. |

| 42. | Marín-Hargreaves G, Azoulay D, Bismuth H. Hepatocellular carcinoma: surgical indications and results. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003;47:13-27. |

| 43. | Ringe B, Weimann A, Tusch G, Pichlmayr R. Resection versus transplantation for malignancy of liver and bile duct. Surgery for gastrointestinal cancer. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven 1997; 513-524. |

| 44. | Pawlik TM, Delman KA, Vauthey JN, Nagorney DM, Ng IO, Ikai I, Yamaoka Y, Belghiti J, Lauwers GY, Poon RT. Tumor size predicts vascular invasion and histologic grade: Implications for selection of surgical treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1086-1092. |

| 45. | Bismuth H, Chiche L, Adam R, Castaing D, Diamond T, Dennison A. Liver resection versus transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients. Ann Surg. 1993;218:145-151. |

| 46. | Achkar JP, Araya V, Baron RL, Marsh JW, Dvorchik I, Rakela J. Undetected hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical features and outcome after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl Surg. 1998;4:477-482. |

| 47. | Ojogho ON, So SK, Keeffe EB, Berquist W, Concepcion W, Garcia-Kennedy R, Imperial J, Esquivel CO. Orthotopic liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Factors affecting long-term patient survival. Arch Surg. 1996;131:935-939; discussion 939-941. |

| 48. | Molmenti EP, Klintmalm GB. Liver transplantation in association with hepatocellular carcinoma: an update of the International Tumor Registry. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:736-748. |

| 49. | Plessier A, Codes L, Consigny Y, Sommacale D, Dondero F, Cortes A, Degos F, Brillet PY, Vilgrain V, Paradis V. Underestimation of the influence of satellite nodules as a risk factor for post-transplantation recurrence in patients with small hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:S86-S90. |

| 50. | Jonas S, Bechstein WO, Steinmüller T, Herrmann M, Radke C, Berg T, Settmacher U, Neuhaus P. Vascular invasion and histopathologic grading determine outcome after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2001;33:1080-1086. |

| 51. | Bruix J, Fuster J, Llovet JM. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Foucault pendulum versus evidence-based decision. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:700-702. |

| 52. | Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, Watson JJ, Bacchetti P, Venook A, Ascher NL, Roberts JP. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology. 2001;33:1394-1403. |

| 53. | Yao FY, Bass NM, Nikolai B, Davern TJ, Kerlan R, Wu V, Ascher NL, Roberts JP. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of survival according to the intention-to-treat principle and dropout from the waiting list. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:873-883. |

| 54. | Roayaie S, Haim MB, Emre S, Fishbein TM, Sheiner PA, Miller CM, Schwartz ME. Comparison of surgical outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis B versus hepatitis C: a western experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7:764-770. |

| 55. | Mazzaferro V, Llovet JM, Miceli R, Bhoori S, Schiavo M, Mariani L, Camerini T, Roayaie S, Schwartz ME, Grazi GL. Predicting survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:35-43. |

| 56. | Sarasin FP, Giostra E, Mentha G, Hadengue A. Partial hepatectomy or orthotopic liver transplantation for the treatment of resectable hepatocellular carcinoma? A cost-effectiveness perspective. Hepatology. 1998;28:436-442. |

| 57. | Saab S, Wang V, Ibrahim AB, Durazo F, Han S, Farmer DG, Yersiz H, Morrisey M, Goldstein LI, Ghobrial RM. MELD score predicts 1-year patient survival post-orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:473-476. |

| 58. | Yao FY, Bass NM, Ascher NL, Roberts JP. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: lessons from the first year under the Model of End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) organ allocation policy. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:621-630. |

| 59. | Helton WS, Di Bisceglie A, Chari R, Schwartz M, Bruix J. Treatment strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:401-411. |

| 60. | Bruix J, Llovet JM. Prognostic prediction and treatment strategy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35:519-524. |

| 61. | Van Kleek EJ, Schwartz JM, Rayhill SC, Rosen HR, Cotler SJ. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: a survey of practices. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:643-647. |

| 62. | Pomfret EA. Early and late complications in the right-lobe adult living donor. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:S45-S49. |

| 63. | Cuomo O, Perrella A, Pisaniello D, Marino G, Di Costanzo G. Evidence of liver histological alterations in apparently healthy individuals evaluated for living donor liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:1823-1826. |

| 64. | Broering DC, Wilms C, Bok P, Fischer L, Mueller L, Hillert C, Lenk C, Kim JS, Sterneck M, Schulz KH. Evolution of donor morbidity in living related liver transplantation: a single-center analysis of 165 cases. Ann Surg. 2004;240:1013-1024; discussions 1024-1026. |

| 65. | Trotter JF, Wachs M, Everson GT, Kam I. Adult-to-adult transplantation of the right hepatic lobe from a living donor. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1074-1082. |

| 66. | Umeshita K, Fujiwara K, Kiyosawa K, Makuuchi M, Satomi S, Sugimachi K, Tanaka K, Monden M. Operative morbidity of living liver donors in Japan. Lancet. 2003;362:687-690. |

| 67. | Livraghi T, Giorgio A, Marin G, Salmi A, de Sio I, Bolondi L, Pompili M, Brunello F, Lazzaroni S, Torzilli G. Hepatocellular carcinoma and cirrhosis in 746 patients: long-term results of percutaneous ethanol injection. Radiology. 1995;197:101-108. |

| 68. | Ryu M, Shimamura Y, Kinoshita T, Konishi M, Kawano N, Iwasaki M, Furuse J, Yoshino M, Moriyama N, Sugita M. Therapeutic results of resection, transcatheter arterial embolization and percutaneous transhepatic ethanol injection in 3225 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective multicenter study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1997;27:251-257. |

| 69. | Lau H, Fan ST, Ng IO, Wong J. Long term prognosis after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: a survival analysis of 204 consecutive patients. Cancer. 1998;83:2302-2311. |

| 70. | Lin SM, Lin CJ, Lin CC, Hsu CW, Chen YC. Radiofrequency ablation improves prognosis compared with ethanol injection for hepatocellular carcinoma < or =4 cm. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1714-1723. |

| 71. | Livraghi T, Goldberg SN, Lazzaroni S, Meloni F, Solbiati L, Gazelle GS. Small hepatocellular carcinoma: treatment with radio-frequency ablation versus ethanol injection. Radiology. 1999;210:655-661. |

| 72. | Livraghi T, Solbiati L, Meloni MF, Gazelle GS, Halpern EF, Goldberg SN. Treatment of focal liver tumors with percutaneous radio-frequency ablation: complications encountered in a multicenter study. Radiology. 2003;226:441-451. |

| 73. | Llovet JM, Real MI, Montaña X, Planas R, Coll S, Aponte J, Ayuso C, Sala M, Muchart J, Solà R. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1734-1739. |

| 74. | Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: Chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37:429-442. |

| 75. | Poon RT, Fan ST, Tsang FH, Wong J. Locoregional therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma: a critical review from the surgeon's perspective. Ann Surg. 2002;235:466-486. |

| 76. | Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, Liu CL, Lam CM, Poon RT, Fan ST, Wong J. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35:1164-1171. |

| 77. | Ferrari FS, Stella A, Pasquinucci P, Vigni F, Civeli L, Pieraccini M, Magnolfi F. Treatment of small hepatocellular carcinoma: a comparison of techniques and long-term results. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:659-672. |

| 78. | Schwartz JD, Schwartz M, Mandeli J, Sung M. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy for resectable hepatocellular carcinoma: review of the randomised clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:593-603. |

| 79. | Chow PK, Tai BC, Tan CK, Machin D, Win KM, Johnson PJ, Soo KC. High-dose tamoxifen in the treatment of inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Hepatology. 2002;36:1221-1226. |

| 80. | Yuen MF, Poon RT, Lai CL, Fan ST, Lo CM, Wong KW, Wong WM, Wong BC. A randomized placebo-controlled study of long-acting octreotide for the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;36:687-691. |

| 81. | Villanueva A, Newell P, Chiang DY, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Genomics and signaling pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:55-76. |