CASE REPORT

A 48-year-old man who was diagnosed with ileal CD as a 27-year-old was referred to our hospital with persistent melena. His family history was negative for this disease. He had no evidence of gluten intolerance. He had been treated with 5-aminosalicylates (5-ASAs) combined with an elemental-diet (ED) therapy and had several hospitalizations for temporary melena in the past two decades. He had not agreed to have an intestinal examination at regular intervals. In January 2007, he was examined by abdominal CT due to persistent melena for 1 year, and multiple metastatic tumors were discovered in the liver (Figure 1A). Blood tests showed a slight anemia (Hb 11.8 g/dL), but he was negative for inflammatory factors. The serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was elevated (31.6 ng/mL; normal range, < 2.5 ng/mL), and wall thickening in part of the ileum was detected by CT (Figure 1B). PET/CT showed accumulations in the multiple hepatic tumors and the wall thickening of the ileum (Figure 2). DBE showed an ulcerative tumor in the ileum about 100 cm away from the ileocecal valve (Figure 3A). There were some longitudinal ulcer scars near the tumor (Figure 3B). An endoscopic forceps biopsy specimen showed microscopically poorly-differentiated adenocarcinoma (Figure 4A and B). Immunohistochemistry of the tumor cells was negative for p58 and positive for β-catenin (Figure 4C and D). Accordingly, he was diagnosed with SBA with hepatic metastases. Although he was treated by chemotherapy with S-1 and cisplatin (CDDP), there was no effective response. He died 4 mo after the diagnosis because of liver failure due to progression of the hepatic metastases.

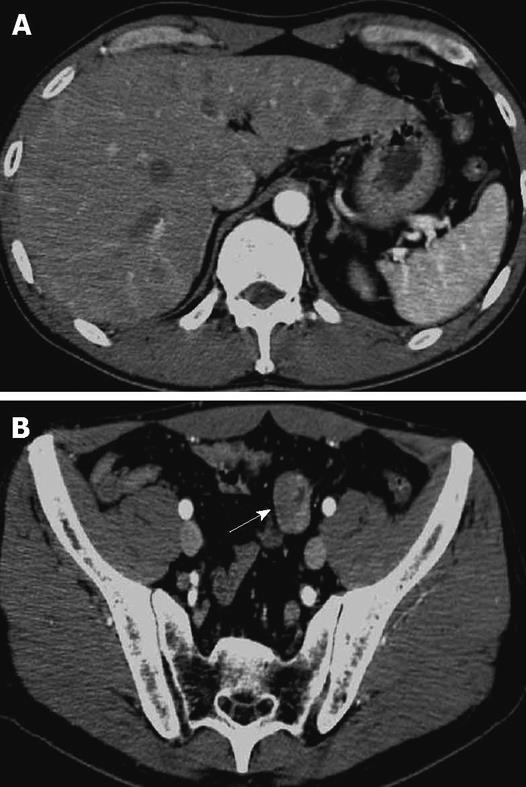

Figure 1 CT findings.

A: Abdominal CT showed the multiple hepatic tumors with ring enhancement; B: Wall thickening of a part of the small bowel (arrow).

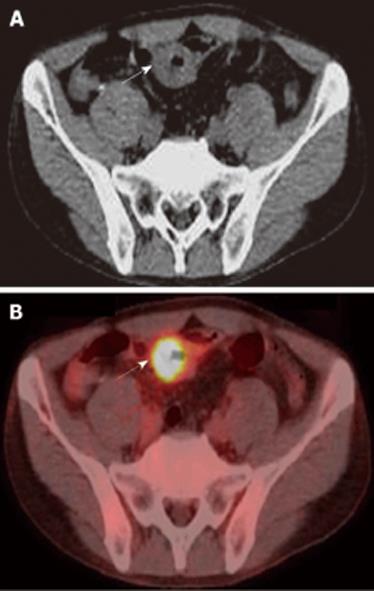

Figure 2 PET/CT findings.

A: Wall thickening of a part of ileum (arrow). B: PET/CT showed 18F-FDG accumulation in the site of wall thickening of ileum (arrow).

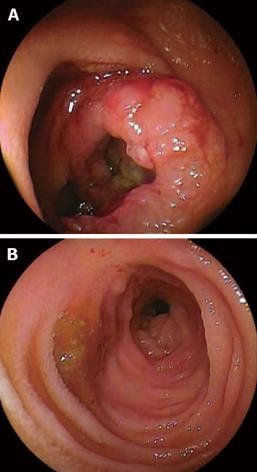

Figure 3 DBE findings.

A: DBE showed ulcerative mass located in the ileum at about 100 cm away from ileocecal valve; B: Some longitudinal ulcer scars near the tumor.

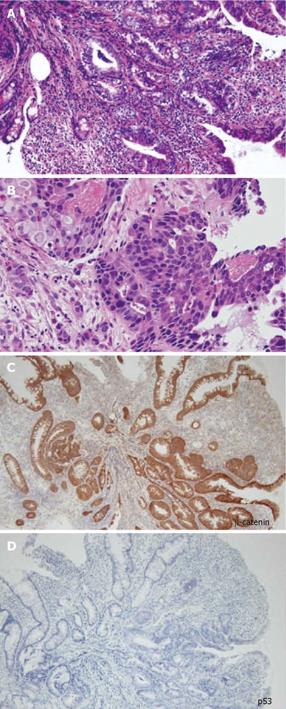

Figure 4 Histopathological findings of the biopsy specimen showed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma.

A: HE (× 100), B: HE (× 400), C: Immunohistochemical staining using β-catenin antibody (× 100), D: Immunohistochemical staining using p53 antibody (× 100).

DISCUSSION

Primary SBA is rare and the incidence is reported to be 1 to 5% of all gastrointestinal tract malignancies[910], and the most important known risk factor for this malignant tumor is previous CD[511]. SBA in CD was reported for the first time by Ginzburg in 1956[12]. The risk for SBA is reportedly higher in patients with CD than in the overall population. Recent meta-analysis revealed the relative risk of SBA in patients with CD as 28.4 (95% CI, 14.5-55.7)[13] to 33.2 (95% CI, 15.9-60.9)[14]. In clinical settings, SBA in CD is difficult to diagnose, and most previous cases were diagnosed after surgery without suspicion of malignancy. Therefore, novel tools are needed to detect and survey the development of this cancer. In our case, we were able to diagnose SBA non-surgically by a novel approach using PET/CT and DBE.

Based on previous reports, Dossett et al[3] summarized the 154 cases of SBA in CD reported in Europe and America. SBA in CD occurred more frequently in males than females (M:F ratio of 2.4:1). The age at diagnosis ranged from 21 to 86 years (mean age, 51.3), and the average duration of CD was 24.5 years (0-45 years)[3]. SBA in CD was observed at a younger age[1] as compared with de novo cancers that were found in 60-69-year-olds[15]. Tumors were found in the ileum at a rate of 75%. The presence of previously bypassed segments of the intestine was 20.3%. Obstruction was the most common manifestation (76%), whereas hemorrhage, fistula, and perforation were observed in 3.9%, 3.9%, and 5.4% of cases, respectively. The majority of diagnoses were made at the time of operation (35.4%) or postoperatively (61.5%). Only 3.1% of the cases could be diagnosed preoperatively. Survival rates after 1 and 2 years were 49.6% and 27%, respectively[3].

In the present case, there were some longitudinal ulcer scars near the tumor, suggesting that chronic inflammation is associated with the development of SBA. Because it is well known that a combination of immunohistochemically strong p53 expression and absent or weak β-catenin expression in ulcerative colitis (UC) patients is evidence for colitis-associated dysplastic lesions[16], we examined the immunohistochemical characteristics of the tumor[17]. In this case, there was no detectable p53 expression, but strong β-catenin expression. Chemotherapy and radiation for SBA have produced disappointing results, and only a few studies have evaluated chemotherapy for unresectable SBA in CD[18]. There have been no controlled studies recommending an effective treatment regimen. Although we treated this patient by systemic chemotherapy with S-1 and CDDP in agreement with the patient, the therapy was not effective and did not seem to prolong the survival time.

There are several previous reports of long-standing risk factors for SBA, including onset of the disease before the age of 30 years, presence of a bypassed segment, chronic active course with stricture and fistulas, male gender, and smoking[1–351119–21]. Corticosteroid and azathioprine therapy to treat CD are also considered potential risk factors. However, 5-ASAs prevent the development of intestinal adenocarcinoma in IBD[122–25]. There is also a theoretical risk for an increased rate of malignancies due to antagonism of TNF-α, but to date, there is no clear proof of such an effect[2627].

Recommendations for screening and surveillance of SBA in CD have been supported by only very limited data[8]. The overall risk of colorectal cancer for UC patients is estimated to be 3.7% (95% CI, 3.2%-4.2%); 2% at 10 years, 8% at 20 years, and 18% at 30 years[28], whereas reported cancerin CD is 0.63%-3.1%[29]. Although diagnostic investigations using conventional modalities such as small bowel series, double-contrast enteroclysis, and upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopies have been performed on patients with a high cancer risk, a recent report found that colonoscopy surveillance may not improve survival even in studying extensive colitis, thus other tools are needed to detect cancer development[8]. CT and MRI are now considered the common imaging modality of choice for abdominal malignancy. Endoscopy of the small intestine, especially capsule endoscopy and DBE, are promising new diagnostic tools[30]. Capsule endoscopy is not invasive, but has a risk of retention for patients with CD who have a stenosis in the intestinal tract[3132]. DBE is a new endoscopic method that provides complete visualization, the ability to biopsy the small bowel, and provides diagnostic and therapeutic information[33].

The recent development of innovative im In this case, PET/CT was effective for the discovery of a small bowel tumor at the initial examination. Although the localization of lesions may not be completely accurate, PET/CT provides accurately fused morphological and functional imaging within a single examination. Today, PET imaging has a high sensitivity for detecting colorectal cancer (CRC) and is superior to conventional CT staging when CRC patients are assessed for local and distant metastases[3435]. PET/CT also offers a better non-invasive tool for identifying and localizing active intestinal inflammation in patients with CD[36]. Although PET/CT is not able to replace conventional studies due to its high cost, it may be useful when conventional studies cannot be performed or are not completed in CD patients. In this case, the tumor was detected at an advanced stage with multiple liver metastases. Although it is still uncertain whether combining PET/CT and DBE will enable us to make an early diagnosis for SBA, this case certainly indicates the possibility of combining PET/CT and DBE without conventional modalities, such as a small bowel series, to detect a primary malignant tumor of the small bowel without surgery. One strategy to monitor high-risk patients might be to perform PET/CT at an initial examination, and then conduct a DBE examination for the patient who has abnormal regions suspected as being malignant.

The recent development of innovative imaging techniques involving PET/CT and DBE has opened a new area in the exploration of the small bowel in CD patients. Each of these techniques is characterized by its own profile of favorable and unfavorable features[30]. Future clinical studies are expected to demonstrate strategies to monitor SBA in CD patients.