Published online Jan 14, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i2.296

Revised: April 25, 2004

Accepted: May 9, 2004

Published online: January 14, 2005

AIM: To study the long-term therapeutic effect of “heart-shaped” anastomosis for Hirschsprung’s disease.

METHODS: From January 1986 to October 1997, we performed one-stage “heart-shaped” anastomosis for 193 patients with Hirschsprung’s disease (HD). One hundred and fifty-two patients were followed up patients (follow-up rate 79%).The operative outcome and postoperative complications were retrospectively analyzed.

RESULTS: Early complications included urine retention in 2 patients, enteritis in 10, anastomotic stricture in 1, and intestinal obstruction in 2. No infection of abdominal cavity or wound and anastomotic leakage or death occurred in any patients. Late complications were present in 22 cases, including adhesive intestinal obstruction in 2, longer anal in 5, incision hernia in 2, enteritis in 6, occasional stool stains in 7 and 6 related with improper diet. No constipation or incontinence occurred in any patient.

CONCLUSION: The early and late postoperative complication rates were 7.8% and 11.4% respectively in our “heart-shaped anastomosis” procedure. “Heart-shaped” anastomosis procedure for Hirschsprung’s disease provides a better therapeutic effect compared to classic procedures.

- Citation: Wang G, Sun XY, Wei MF, Weng YZ. Heart-shaped anastomosis for Hirschsprung’s disease: Operative technique and long-term follow-up. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(2): 296-298

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i2/296.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i2.296

During the period from 1955 to 1985, more than 400 children received classic operations, including modified Duhamel, Soave, and Ikeda operations, etc, for Hirschsprung’s disease (HD) in our hospital. Because of a high incidence of complications following these methods[1], we have changed to use a “heart-shaped anastomosis” designed by ourselves since January 1986. During the ten years from 1986 to 1997, we performed this procedure for 193 patients with HD. This procedure could not only effectively prevent the occurrence of postoperative complications, such as infection in wound or abdominal cavity, anastomotic leakage and stricture, but also significantly decrease the incidence of incontinence or soiling and recurrence of constipation after surgery. This article reports the outcome of “heart-shaped anastomosis” procedure in HD.

All the 193 cases (155 boys and 38 girls) were diagnosed on the basis of clinical history, radiological studies, rectoanal manometry, and pathologic examination after surgery. The mean age of the patients was 25 mo (range from 9 d to 10 years). Among these patients, short-segment aganglionosis was found in 172 cases and long-segment aganglionosis was found in 21 cases. The descending colon was pulled down for anastomosis in 130 cases, the ascending colon was pulled down for anastomosis in 63 cases, including 21 with intestinal neuronal dysplasia (IND).

The operation was performed as previously described[1]. A low left transverse incision was made extending slightly to the right of the midline. The peritoneal reflection from the rectum was dissected on both the left and right sides down to just above the level of the dentate line. To protect the pelvic autonomic nervous system, the upper third of the lateral rectal ligaments was dissected as close as possible to the rectal wall. Hemostasis was achieved with a sponge pressed into the posterior cavity behind the rectum. The proximal ganglionic bowel was identified with operative biopsies and frozen section. Aganglionic bowel was then dissected and mobilized up to the splenic flexure to allow a tension-free anastomosis with an adequate blood supply.

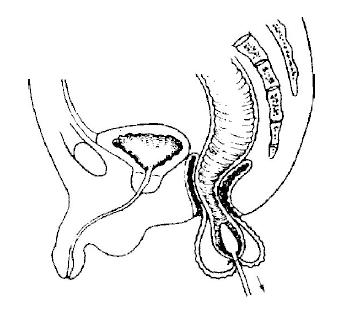

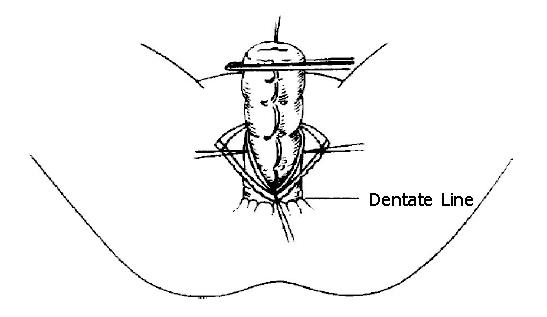

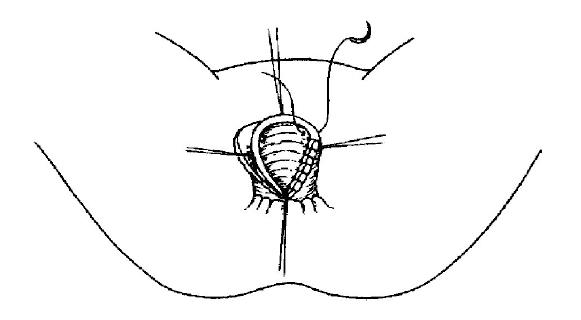

Attention was then paid to the perineum. The anus was dilated. An olive-shaped dilator was inserted via the anus into the lumen of rectosigmoid and aganglionic rectum was fastened to the dilator at the transition level. The bowel was then prolapsed out of the rectum, and everted (Figure 1). The rectum was transected and the ganglionic bowel was pulled through the anal canal. The most dilated distal portion of aganglionic bowel was resected at this point. The posterior wall of aganglionic anorectum was split longitudinally to the level of the dentate line (Figure 2). The tips of the two halves were trimmed so that the remaining rectal wall, whose anterior aspect was longer than the posterior one, had the shape of a heart. A point of anastomosis in anterior wall was marked at 2 cm above the anal verge and the proximal bowel opposite to this point was shortened about 2.5 cm for avoiding the formation of a valve. The point of anastomosis in posterior wall was marked at 0.5 cm above the dentate line (Figure 3). Interrupted sutures were placed circumferentially at each quadrant through the seromuscular coats of the proximal bowel and the full-thickness edge of the transected rectum. Each suture was tied and grasped with clamps to prevent retraction. Subsequent sutures were added to each quadrant as full-thickness bites to complete the anastomosis. In order to prevent leakage, the posterior wall was meticulously sutured. At completion of the procedure, the anterior anastomosis was 4 cm above the anal verge and the posterior anastomosis was 2 cm above the anodermal junction.

Among the 193 patients, 152 patients received complete follow-up (follow-up rate 79%). The follow-up time ranged from 24 mo to 140 mo (mean 80 mo).

Early postoperative complications occurred in 15 (7.8%) patients, including urine retention in 2 who recovered following the insertion of a urethral catheter 1wk after operation, enteritis in 1, anastomotic stricture in 1, and intestinal obstruction in 2 who were cured with Chinese herbals. No infection in celiac/pelvic cavity or wound, and anastomotic leakage or death occurred in any patient.

Late complications occurred in 22 (11.4%) patients, such as adhesive intestinal obstruction in 2 who were treated with adhesive bowel resection, constipation due to longer remaining anal canal in 5 who were treated with a strip of internal sphincter cut, incision hernia in 2, enteritis in 6, occasional soiling in 7 and 6 related with improper diet. No incontinence or recurrence of constipation was found in any patient.

A number of operating procedures have been reported for treating HD. Previous studies have shown that the incidence of early postoperative complications in these procedures is over 25%, and the late complication rate is approximately 40%[2-4]. However, these two complication rates in our “heart-shaped anastomosis” procedure were 7.8 and 11.4%, respectively.

The incidence of infection in celiac/pelvic cavity or wound was approximately 7 to 17% in our study. Unlike other operations in which resection and anastomosis of the colon are performed in abdominal cavity, they were performed outside the abdominal cavity in our study and contamination or infection could be avoided.

Anastomotic leakage is usually the most severe complication in HD, and the incidence is 3 to 15.5%[2]. It often causes septic infection in the abdominal or pelvic cavity and needs colostomy to save the patient’s life. In some patients, anastomotic leakage can result in multi-fistulae in pelvic cavity, frozen pelvis or constipation, and even lifelong artificial anus. In our procedure, the splenic flexure and left transverse colon are mobilized sufficiently, so that the colon could be pulled-through easily for a tension-free anastomosis outside the anus. On the other hand, a clear field of vision and reliable manipulation also allow us to avoid the occurrence of anastomotic leakage.

The occurrence of anastomotic stricture is related to ring-stricture at anastomosis, necrosis due to clamping of the bowel and its incidence is about 10%[2]. The “oblique anastomosis” procedure could prevent ring-stricture at the anastomosis and avoid anal dilatation within 3-5 mo after operation[1]. In our patients, valvular stricture in anterior wall was found in one patient due to reservation of anterior coloanal wall and cured by dilating anus.

Because more than half of the internal sphincter is resected in most operations, the incidence of soiling or constipation is approximately 10 to 20%[2,5]. However, our procedure could retain almost all the internal sphincter, so that it prevents recurrence of constipation and decreases the incidence of soiling. On the other hand, this procedure cut off the internal sphincter in the posterior wall, thus preventing spasm of the internal sphincter after operation.

It has been reported that recurrence of incontinence is related to insufficient resection of pathologic colon or/and too much reservation of aganglionic rectum[4]. In our operation, the splenic flexure and transverse colon were regularly mobilized and aganglionic colon was removed sufficiently, therefore recurrence of incontinence was avoided. In our study, a longer rectum was preserved in 5 patients, who were managed by resection of internal sphincter.

This procedure cannot prevent the occurrence of enterocolitis, which is about 8 to 25%. Further studies are needed to elucidate the reason for the occurrence of enterocolitis.

In summary, “heart-shaped” anastomosis for HD provides a clear field of vision, follows simplified steps of operation, there is no need for a colostomy, minimal mobilization of pelvic cavity, and placement of urethral catheter is not needed. Colon can be resected outside the anus, and oblique colorectal anastomosis is performed end-to-end, thus minimizing the chance of contamination in abdominal/pelvic cavity. Rectal blind pouch, septum, infection or rupture of anastomosis are also avoided. There is no need to dilate anus after operation. No special clamps or stapling devices are required and complications resulting from them are avoided and nursing work is simplified. Not only the internal sphincter is persevered to a maximum degree but also the internal sphincter spasm syndrome is avoided, thereby solving the problems of soiling, incontinence and recurrence of constipation. Currently, this procedure has been widely used in many hospitals in China[6-9].

Edited by Wang XL and Kumar M

| 1. | Wang G, Yuan J, Zhou X, Qi B, Teitelbaum DH. A modified operation for Hirschsprung's disease: Posterior longitudinal anorectal split with a "heart-shaped" anastomosis. Pediatr Surg Int. 1996;11:243-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shono K, Hutson JM. The treatment and postoperative complications. Pediatr Surg Int. 1994;9:362-365. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Reding R, de Ville de Goyet J, Gosseye S, Clapuyt P, Sokal E, Buts JP, Gibbs P, Otte JB. Hirschsprung's disease: a 20-year experience. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:1221-1225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Skaba R, Dudorkinova D, Lojda Zd, Dvorakova H, Pycha K, Kabelka M. Kasai’s rectoplasty in the treatment Hirschsprung’s disease and other types of colorectal dysganlionosis of in children. Pediatr Surg Int. 1994;9:503-506. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Kobayashi H, Hirakawa H, Surana R, O'Briain DS, Puri P. Intestinal neuronal dysplasia is a possible cause of persistent bowel symptoms after pull-through operation for Hirschsprung's disease. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:253-257; discussion 257-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang ZL, Li P, Zhang YN, Niu XY, Shi SN. Long-term results of pull-through heart-shape colorectotomy to treat Hirschsprung’s disease. Zhonghua Xiaoer Waike Zazhi. 2003;24:127-128. |

| 7. | Li SC, Wu BY, Zheng HM, Dai YJ, Ye T, Wang YJ. Stump anorectal longitudinal incision and colorectal heart-shape anastomosis for the treatment of Hirschsprung’s disease. Zhonghua Putong Waike Zazhi. 2001;15:651-652. |

| 8. | Yi J, Jiang JP, Li T, Jiang B, Chen YD, Liu DL, Liu JY, Gu XL. Trans-anal colonic pull-through for Hirschsprung’s disease. Zhonghua Xiaoer Waike Zazhi. 2001;22:265-266. |

| 9. | Wang GB, Tang ST, Lu XM, Yuan QL, Guo XL, Tao KX, Liu CP. Primary laparoscopic-assisted pull-through for hirschsprung’s disease in infants and children. Zhonghua Xiaoer Waike Zazhi. 2001;22:136-137. |