Copyright

©The Author(s) 2021.

World J Gastroenterol. Jul 7, 2021; 27(25): 3940-3947

Published online Jul 7, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i25.3940

Published online Jul 7, 2021. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i25.3940

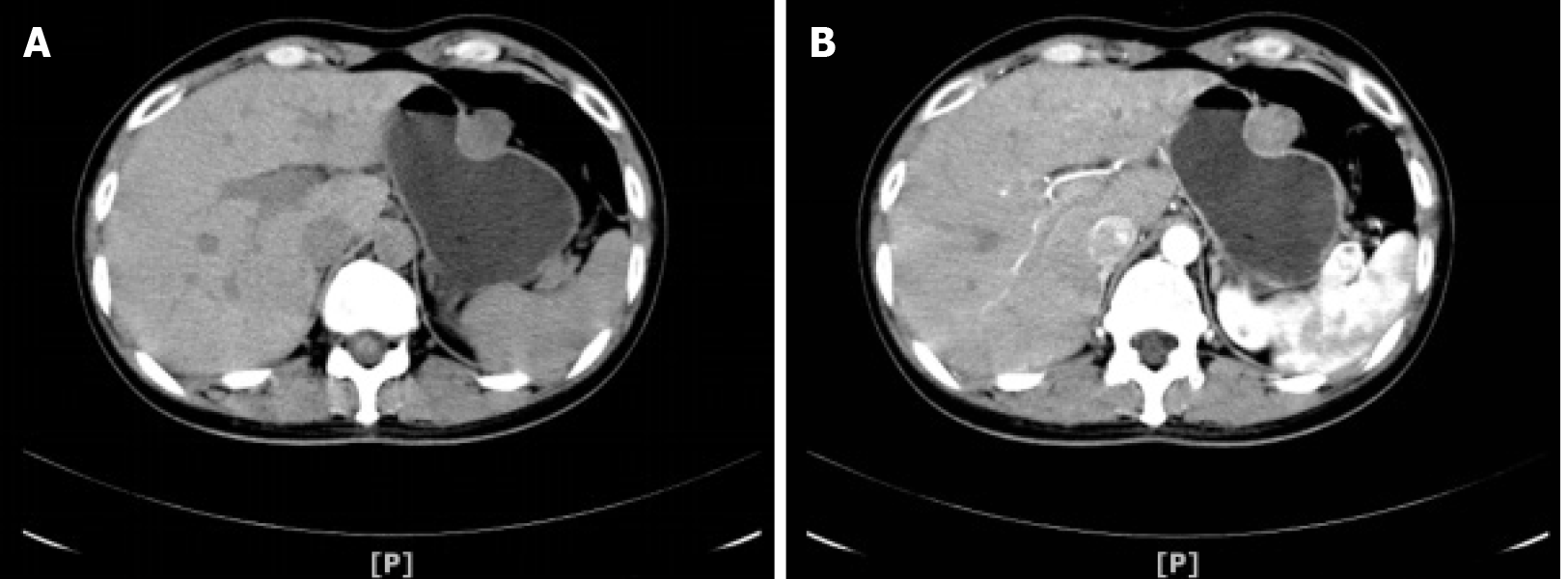

Figure 1 Abdominal computed tomography scanning.

A: Computed tomography scan revealed a rounded mass arising from the greater curvature of the gastric body; B: The gastric mass exhibited slight internal contrast enhancement.

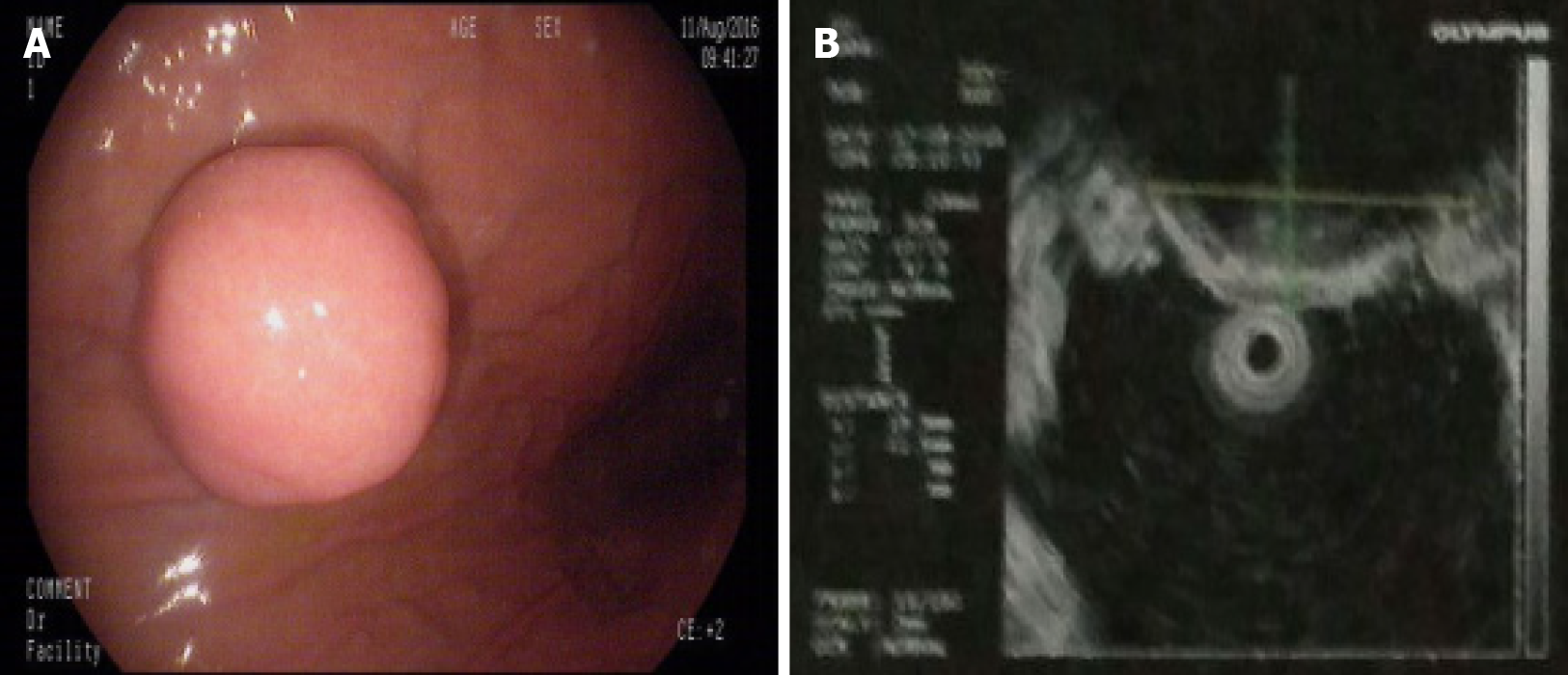

Figure 2 Gastroscopy and endoscopic ultrasonography.

A: Gastroscopy demonstrated a hemispherical protrusion lesion of the gastric body; B: Endoscopic ultrasonography showed that the lesion arose from the muscularis propria.

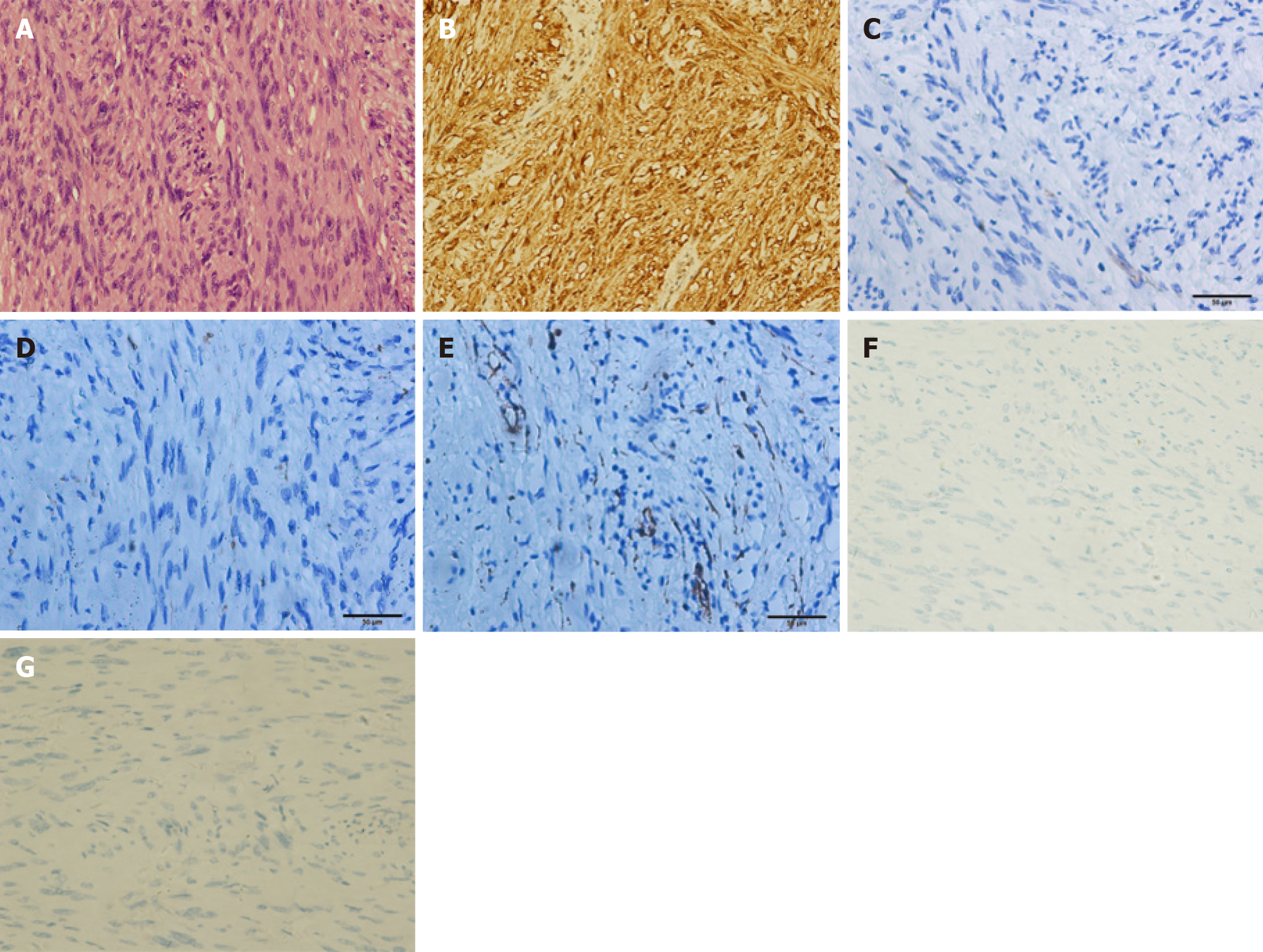

Figure 3 Pathological analysis and immunohistochemical staining.

A: Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed spindle cell tumors with mild cells, mitotic figures 1-2/50 high-power field, local inflammatory cell infiltration, and no necrosis. Combined with immunohistochemistry and gene detection results, the results were consistent with schwannoma; B-G: Immunohistochemical staining of the gastric mass confirmed a gastric schwannoma through positive staining for S-100 protein (B), whereas CD117 (C), CD34 (D), α-smooth muscle actin (E), desmin (F), and DOG1 (G) were negative.

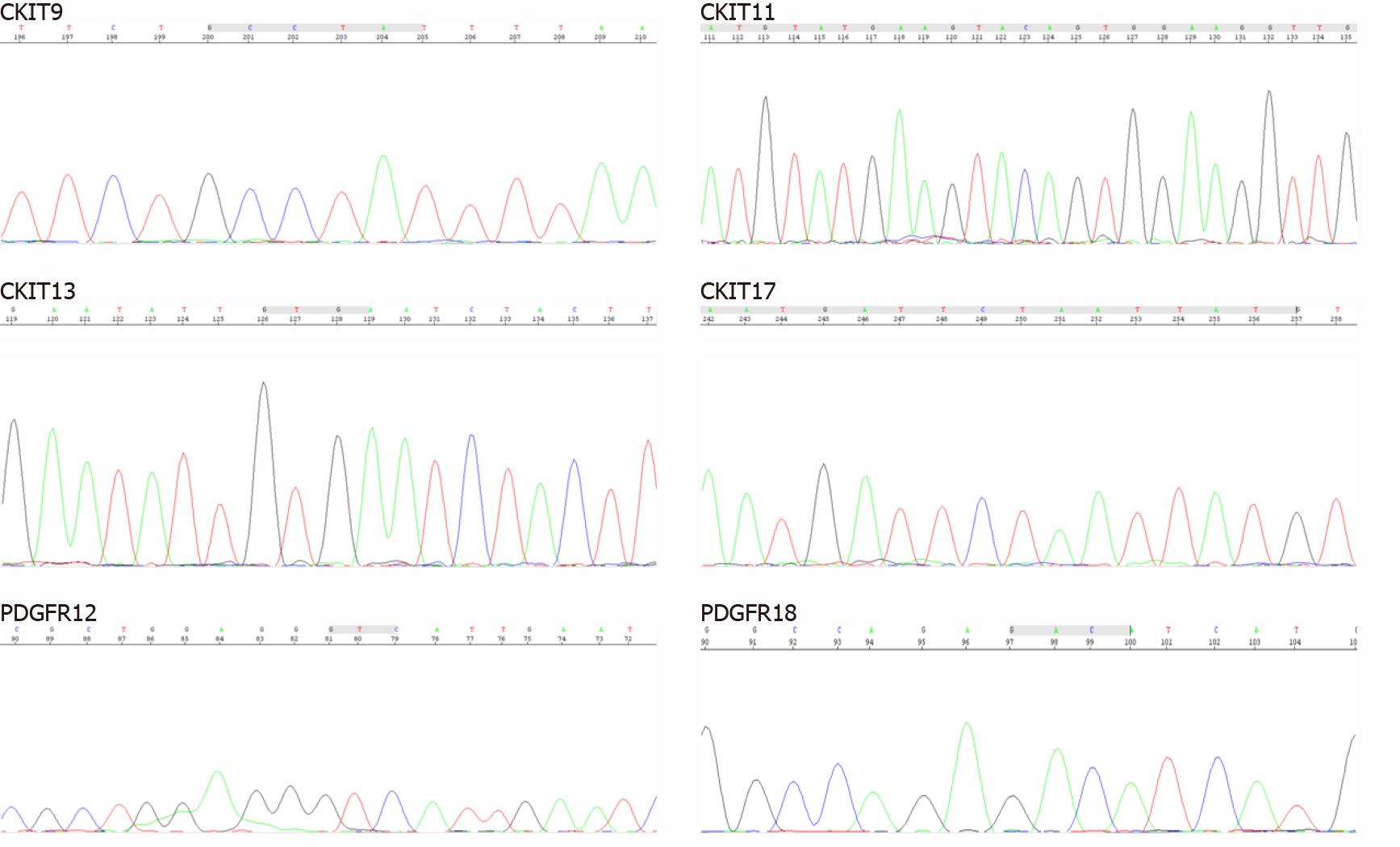

Figure 4 c-Kit and PDGFRA gene mutational analysis.

DNA sequencing electropherograms revealed an absence of mutations in exons 9, 11, 13, and 17 of the c-Kit gene and exons 12 and 18 of the PDGFRA gene.

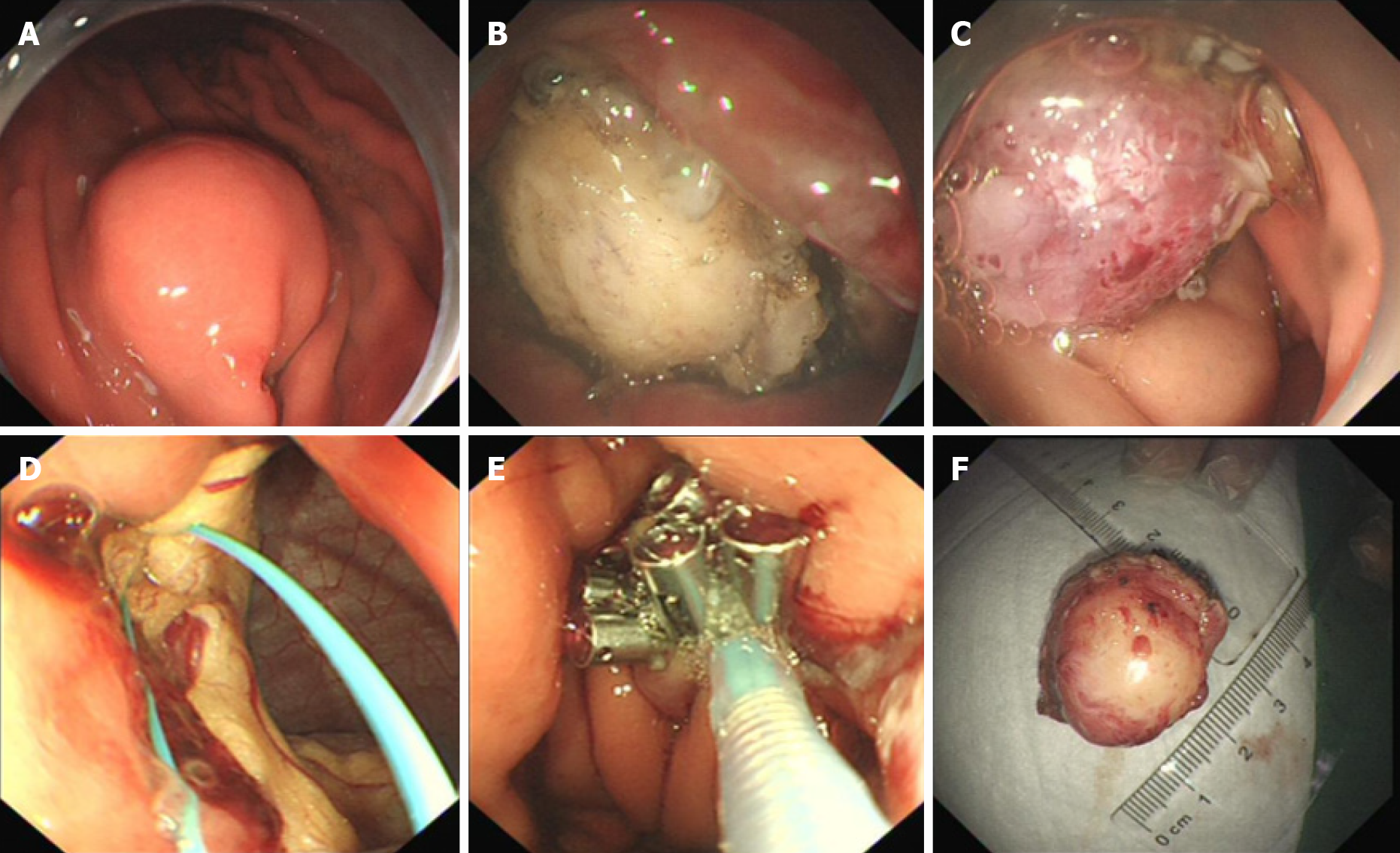

Figure 5 Endoscopic full-thickness resection operative process.

A: Marked the lesion with argon plasma coagulation; B and C: Application of the insulated-tip knife to isolate the stromal tumor along its periphery; D and E: An “artificial perforation” observed after stromal tumor resection and sealed the perforation by endoscopic purse-string suture; F: The resected tumor.

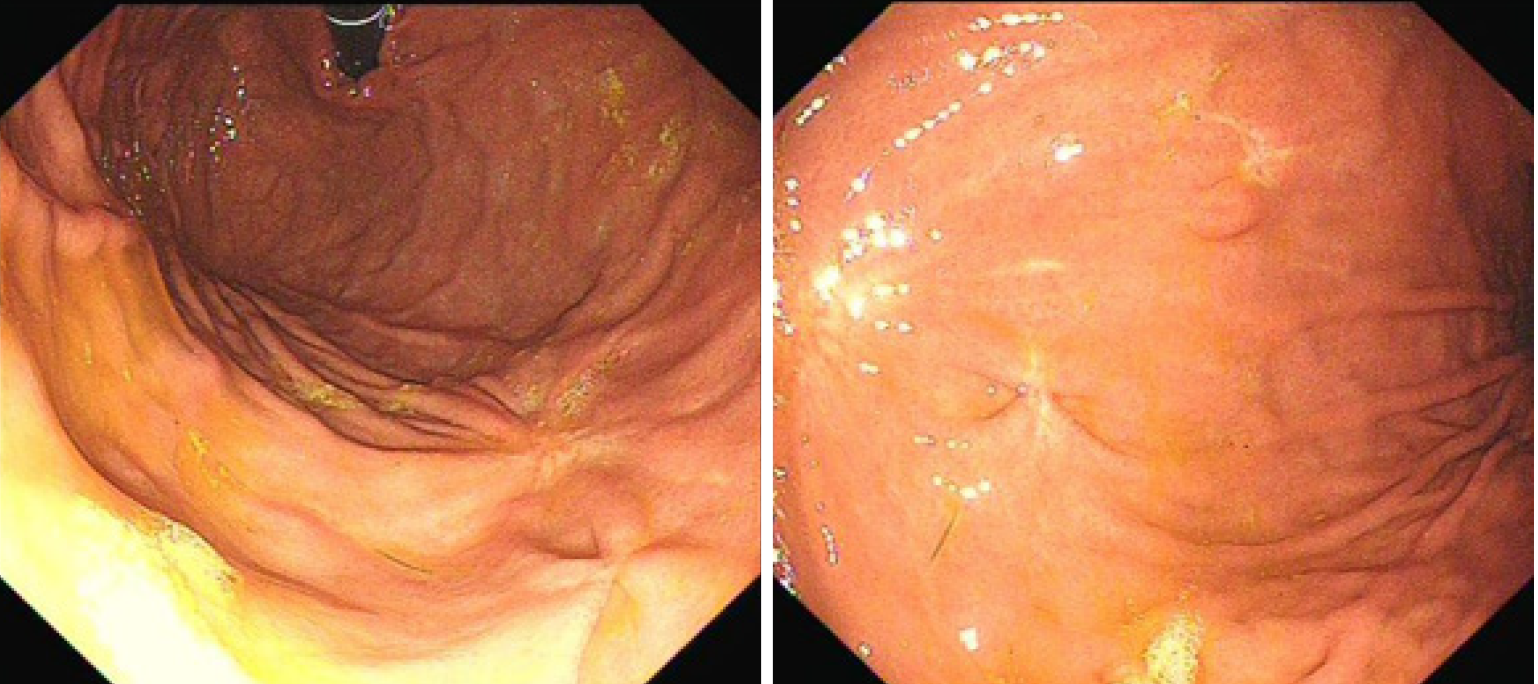

Figure 6

Gastroscopy at 16 mo after the operation revealed that the incision recovered well and that there was no recurrence.

- Citation: Lu ZY, Zhao DY. Gastric schwannoma treated by endoscopic full-thickness resection and endoscopic purse-string suture: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27(25): 3940-3947

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v27/i25/3940.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v27.i25.3940