Copyright

©The Author(s) 2016.

World J Gastroenterol. Jan 14, 2016; 22(2): 600-617

Published online Jan 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i2.600

Published online Jan 14, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i2.600

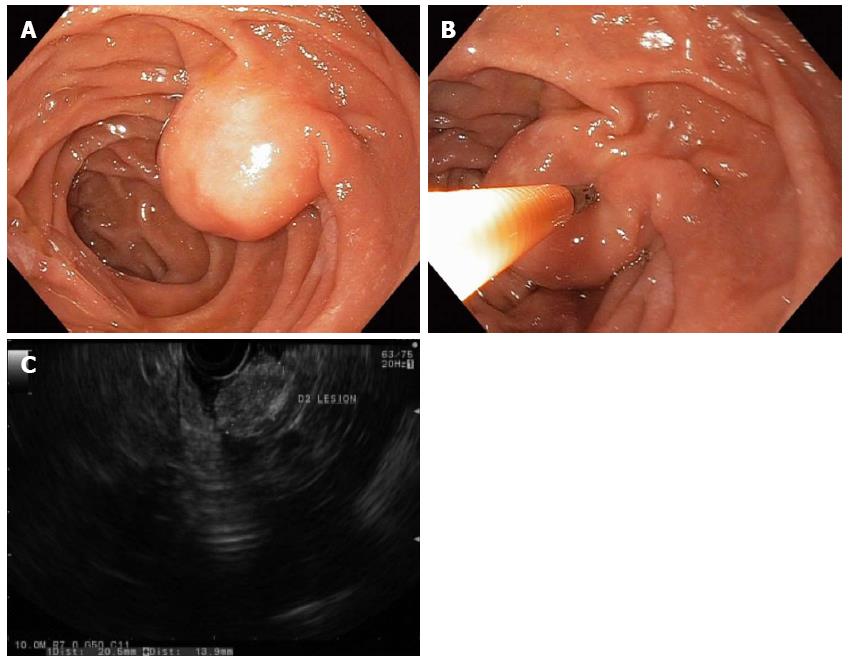

Figure 1 Duodenal lipomas are benign, subepithelial, adipose tumors that rarely cause symptoms.

A round subepithelial lesion was found in the second-portion of the duodenum (A); which had a positive “pillow sign” suggesting a lipoma (B); endoscopic ultrasonography found a 2.1-cm hyperechoic lesion arising from the submucosal layer, which was diagnostic of a lipoma (C). As such, endoscopic therapy was not required.

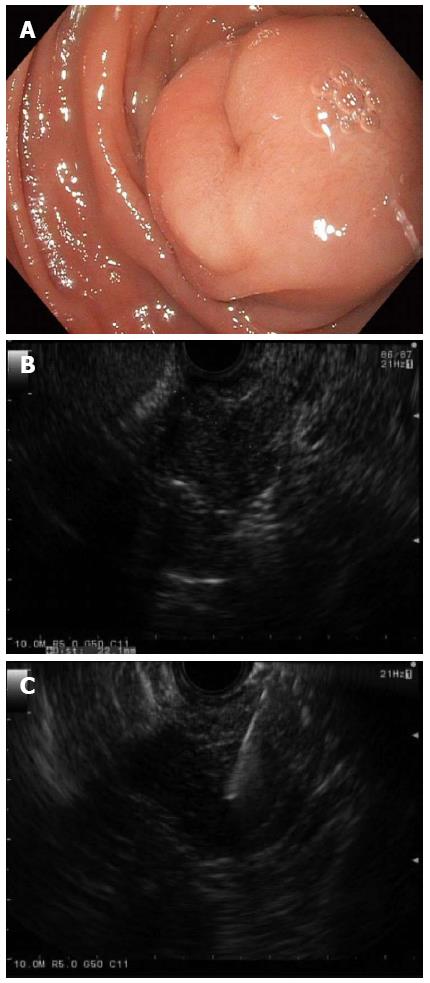

Figure 2 Gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

A: A large subepithelial lesion with a central “dimple” or depression was seen in the duodenum by white light endoscopy; B: Linear endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) identified a 2.2-cm hypoechoic lesion arising from the deep muscle layer, which suggested a GI stromal tumor (GIST) or leiomyoma; C: EUS with fine needle aspiration enabled cytopathologic confirmation of a GIST; and this tumor was later removed by surgical excision.

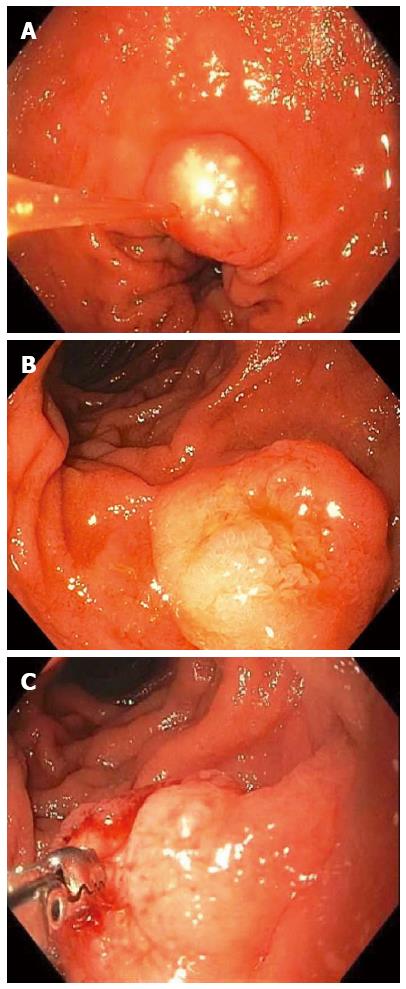

Figure 3 Non-ampullary duodenal carcinoid tumors.

A 1-cm duodenal nodule was seen with a white lesion visible in or just below the mucosa, which was suspicious for a carcinoid tumor (A); A larger 1.5-cm subepithelial lesion was found elsewhere in the duodenum of the same patient (B); Bite-on-bite biopsies through the mucosal layer revealed white tissue that was able to be pathologically sampled confirming the diagnosis of a duodenal carcinoid (C).

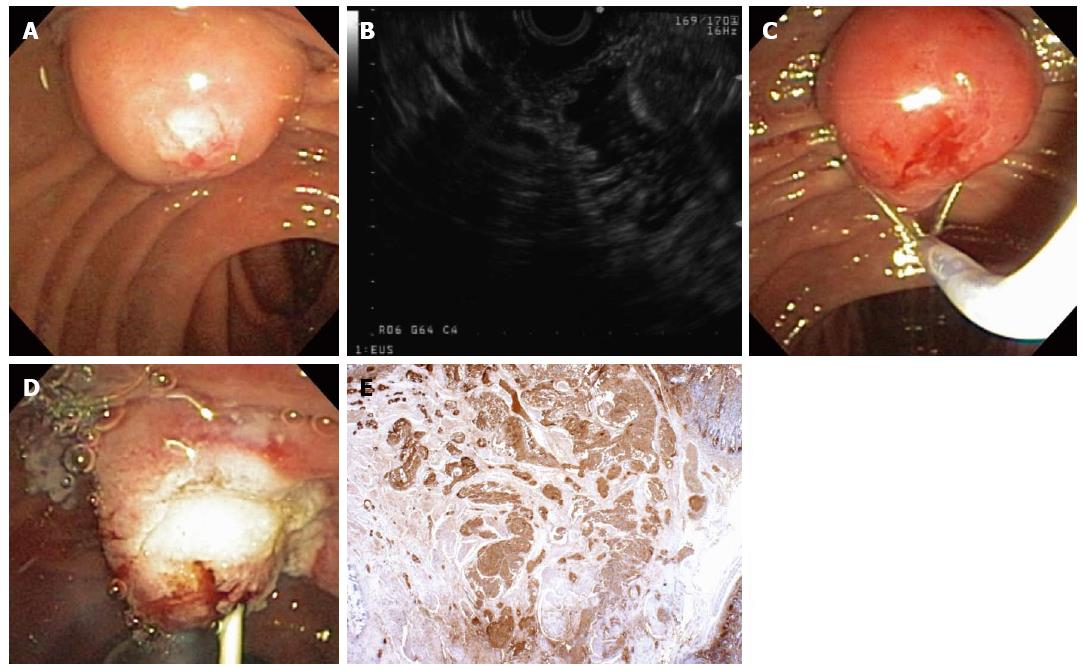

Figure 4 A 55-year-old woman was found to have an ampullary mass on upper endoscopy for abdominal pain.

Magnetic resonance imaging showed an ampullary tumor with no locoregional invasion or hepatic metastases. Mucosal biopsies showed no pathologic abnormality. The patient was referred for endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and possible ampullectomy. On duodenoscopy, a large, irregular ampulla was seen with a whitish hue at the ampullary os (A); EUS demonstrated a 1.6-cm, round, hypoechoic ampullary mass that did not invade into the muscularis propria or into the pancreas (B); On attempted hot-snare resection (C), the lesion was very hard and the snare slipped off the lesion resecting only the surface mucosa, which revealed a white ampullary carcinoid tumor. Ampullectomy was aborted, a biliary sphincterotomy was performed, and a prophylactic pancreatic duct stent was placed (D); Histopathology showed nests of neoplastic cells that stained strongly with antibodies to chromogranin (immunoperoxidase × 20) that extend from the surface epithelium (top and to the right), which confirmed a carcinoid tumor (E). The patient underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy with a curative (R0) resection and no lymph node metastases.

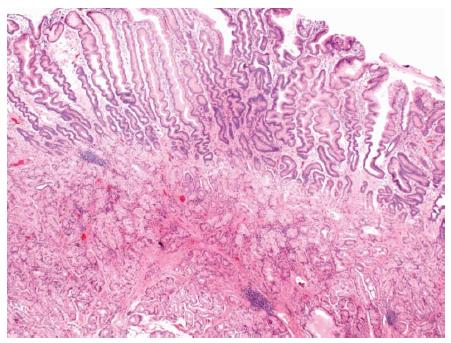

Figure 5 Brunner’s gland hyperplasia was found on histopathology from a sessile polyp that was endoscopically resected from the duodenal bulb.

Brunner’s glands extend to the base of the sample. The surface is reactive with extensive gastric metaplasia (HE × 20).

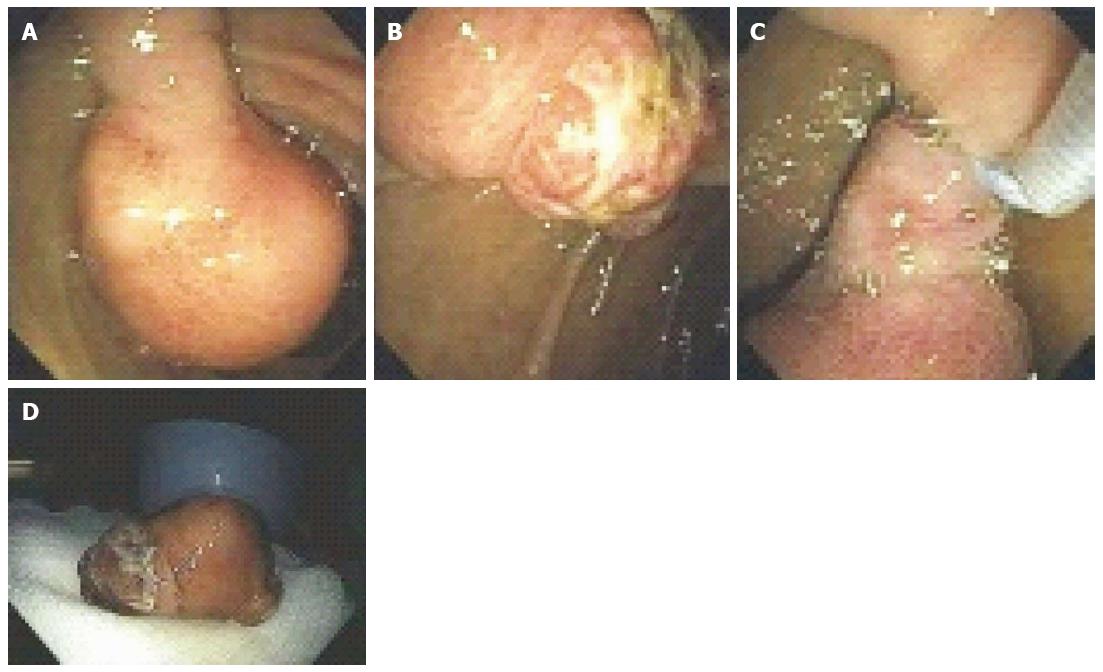

Figure 6 A 53-year-old man presented with exertional dyspnea and 2 wk of melena.

For symptomatic anemia, he received 8 units of packed red blood cells over several days. Upper endoscopy showed a 3.5-cm pedunculated polyp on a wide stalk in the posterior duodenal bulb (A, B); An endoloop was placed using a duodenoscope (C) followed by en to snare resection; The resected polyp was so large the bite block had to be removed in order to pull the polyp out of the mouth (D). Pathology showed a Brunner’s gland “adenoma”.

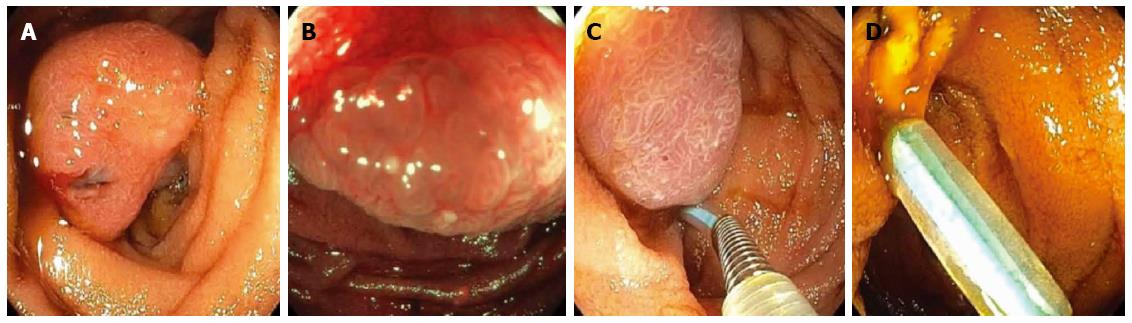

Figure 7 A patient presented for endoscopy because of gastrointestinal bleeding.

A solitary Peutz-Jeghers hamartomatous polyp was seen in the duodenum on white light (A) and narrow-band imaging (B); This large polyp was removed endoscopically by first using an endoloop to constrict the broad stalk of the polyp (C); followed by hot-snare resection (D).

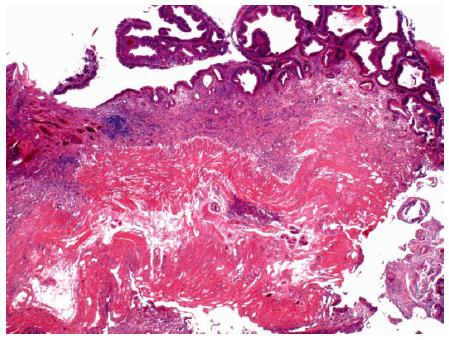

Figure 8 Photomicrograph of a large tubular adenoma that was removed in piecemeal fashion by underwater endoscopic mucosal resection from the second-portion of the duodenum.

Dark, adenomatous epithelium lines the surface of the mucosa (top). The muscularis mucosa is cauterized at the base (HE × 20).

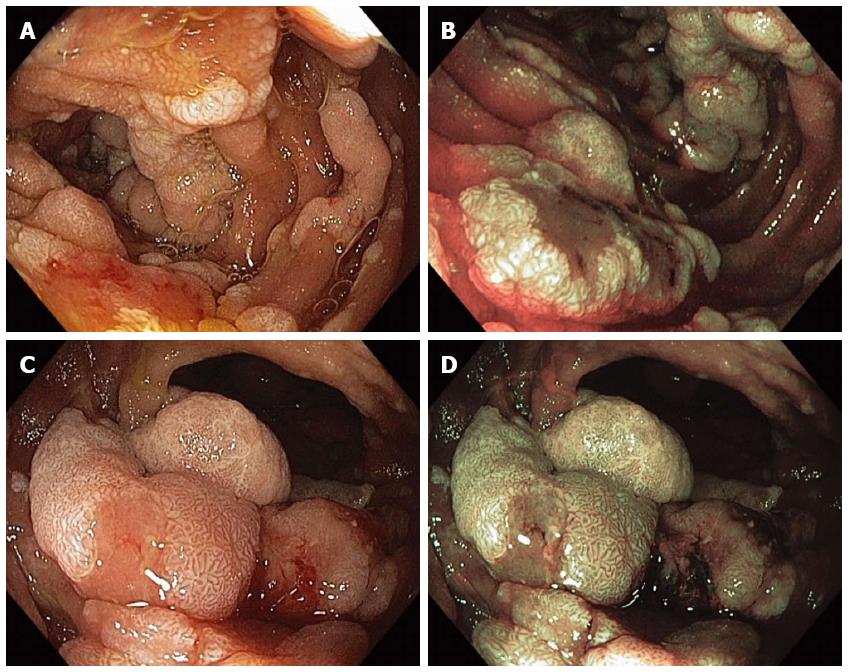

Figure 9 Multiple sessile adenomatous polyps were found in various portions of the duodenum in a patient with familial adenomatous polyposis.

Duodenal polyps were visualized with high-definition white-light (WL) endoscopy (A) and narrow-band imaging (NBI) endoscopy (B); The largest adenomas were carefully examined under WL (C) and NBI (D) as they have an increased risk for harboring malignancy.

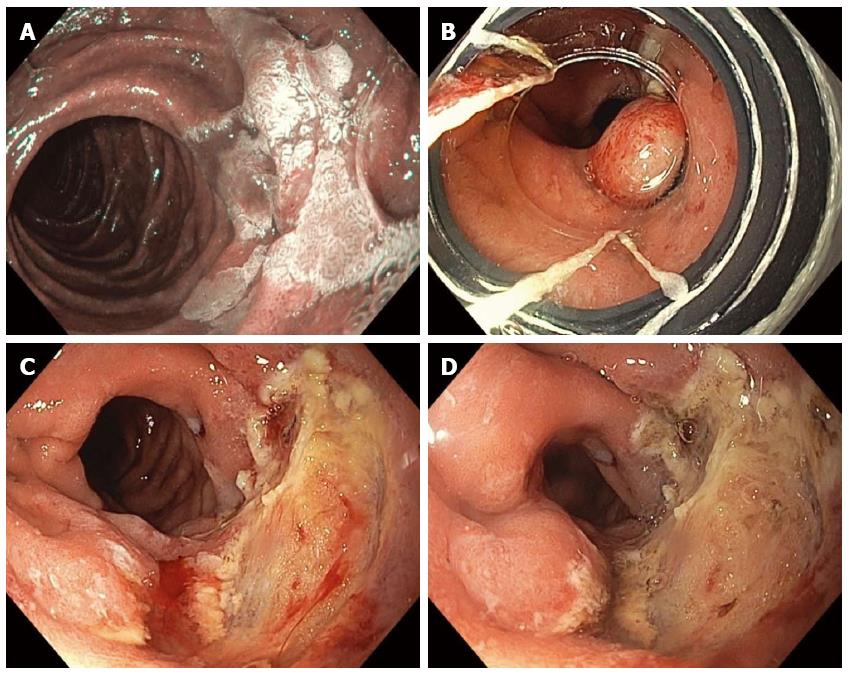

Figure 10 Piecemeal cap-band-assisted mucosectomy (endoscopic mucosal resection).

A large, 2.5-cm, nearly flat, duodenal adenoma was found in the second portion of the duodenum along the lateral wall and was examined with narrow-band-imaging, which did not reveal any invasive cancer (A); Cap-band-assisted EMR was performed. Two bands were sequentially deployed (B) and the resultant pseudopolyps were resected leaving behind no macroscopic evidence of residual adenoma (C); Argon plasma coagulation was used to ablate the borders of the polyp and exposed submucosal vessels in order to reduce the risk of adenoma recurrence and delayed bleeding, respectively (D).

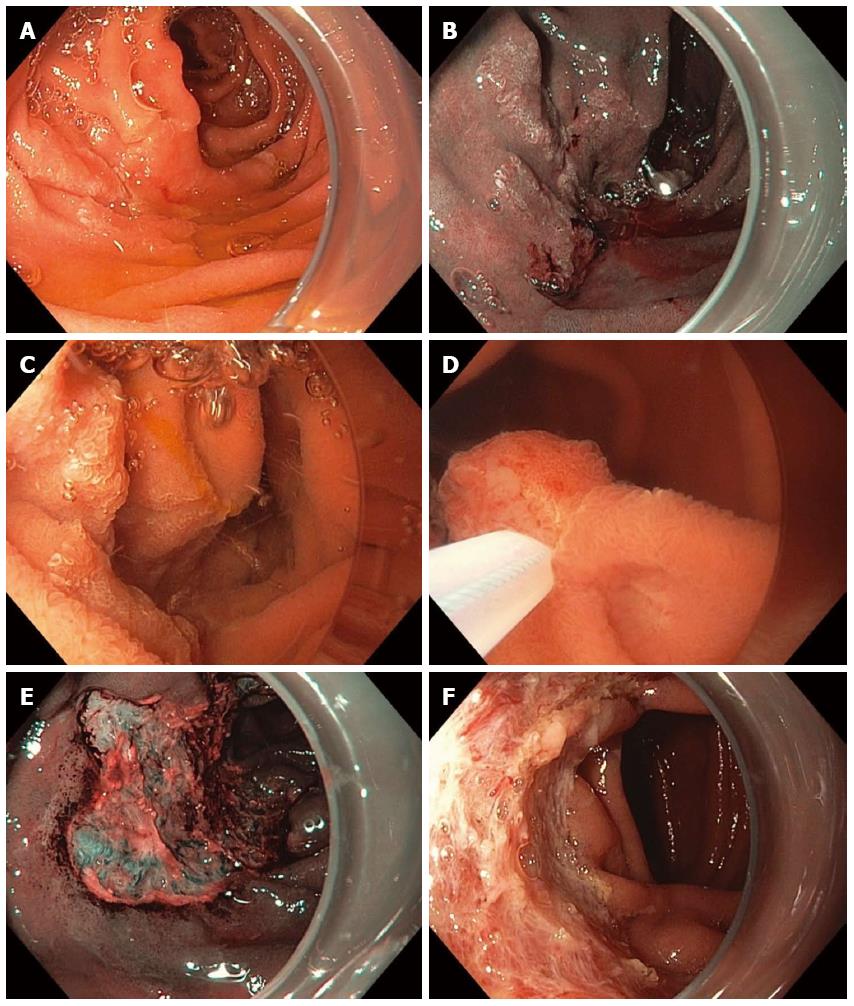

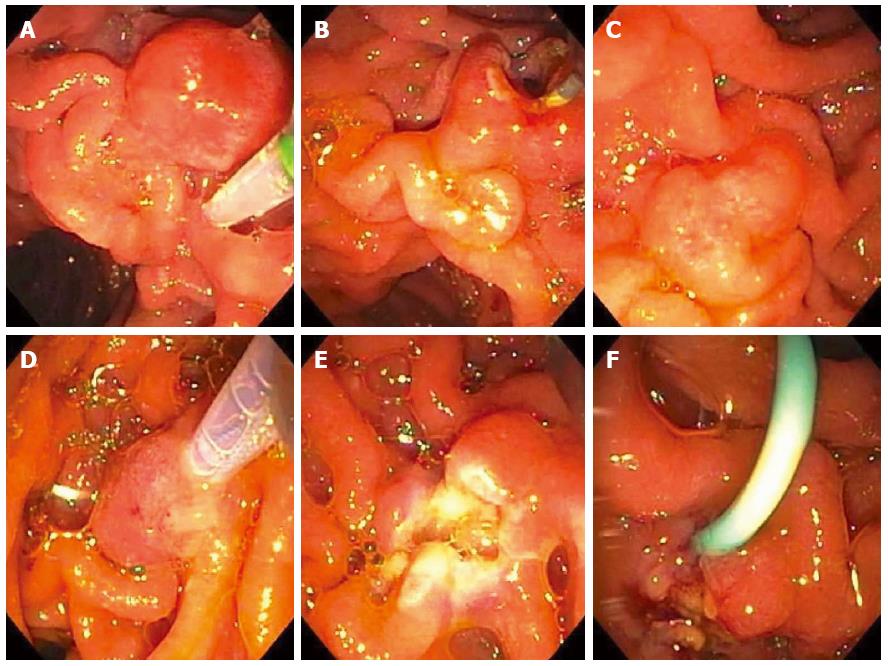

Figure 11 Piecemeal underwater endoscopic mucosal resection.

A large, 3-cm, non-ampullary, laterally spreading adenoma was found in the second portion of the duodenum (A); Narrow-band imaging (NBI) demonstrated adenoma without evidence of invasive cancer (B); Carbon dioxide gas that was used for insufflation was removed and water infused (C); A 15-mm crescent snare (D) was used for piecemeal underwater endoscopic mucosal resection (UEMR). The electrosurgical settings used for snare resection were DRYCUT 60 W, Effect 4, using a VIO 300D generator (ERBE USA, Marietta, GA). NBI was used to identify a residual island of adenoma (E, seen just inside the “9 o’clock” margin of the resection). Final images showed complete endoscopic resection (F).

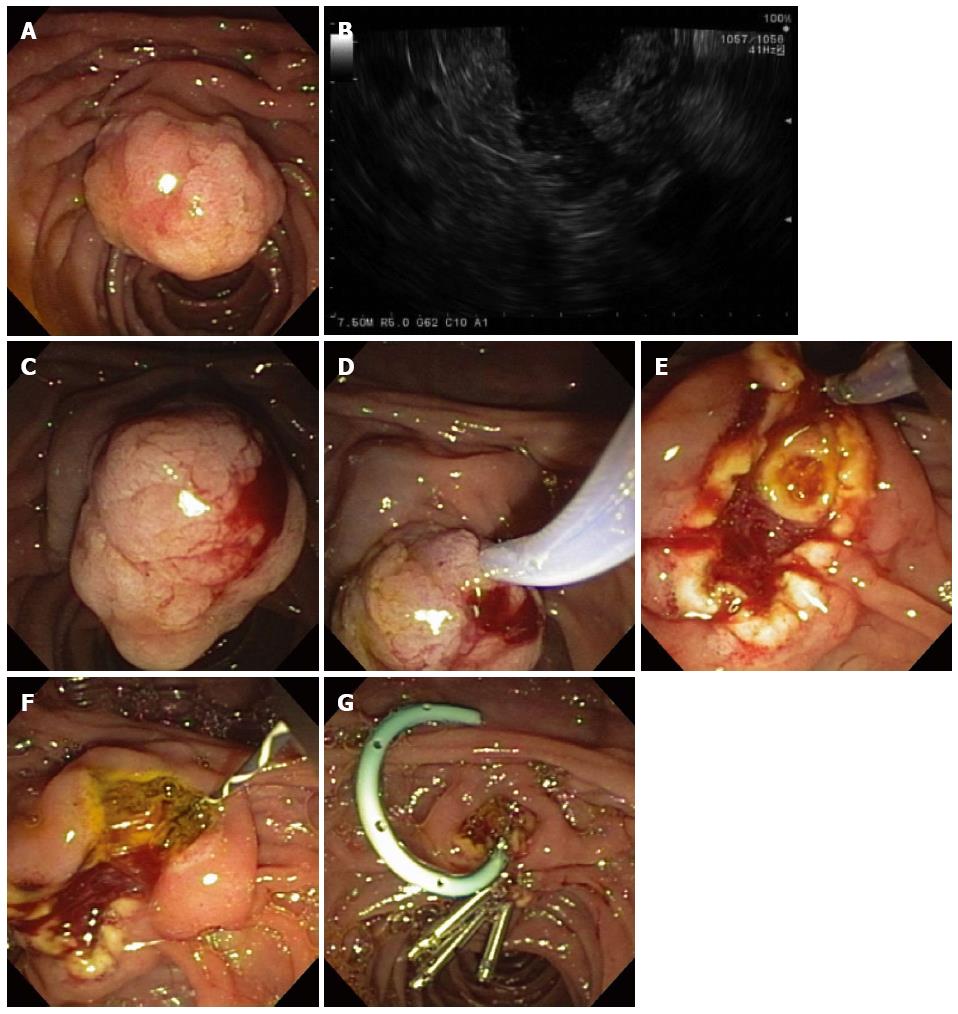

Figure 12 Ampullary evaluation followed by endoscopic papillectomy and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

A 2-cm adenoma of the Ampulla of Vater (major papilla) was referred for endoscopic management (A); Endoscopic ultrasonography showed no invasion of the ampullary lesion into the duodenal muscularis propria or pancreas (B); Sterile normal saline was injected to lift the ampullary adenoma (C); after which hot-snare resection was accomplished (D); The adenoma was resected en bloc and the cut distal bile duct was evident following papillectomy (E); A biliary sphincterotomy was performed (F) and a 5-Fr, 4-cm-long, polyethylene, single-pigtail stent was placed into the pancreatic duct of Wirsung (G). Rectal indomethacin was also administered to reduce the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Endoclips were used to provide mucosal closure of the inferior margin of the resection.

Figure 13 A 63-year-old woman presented with chronic abdominal pain and recurrent acute pancreatitis in the setting of pancreas divisum.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for minor papillotomy and pancreatic duct (PD) stenting was intended. During ERCP, the minor papilla was found to be enlarged to about 1-cm in size and was somewhat hard on palpation with the sphincterotome (A). A minor papillotomy was performed (B), the minor papilla was biopsied, and a pancreatic duct (PD) stent was placed. Pathology showed adenoma, and the patient returned for minor papillectomy several weeks later. The prior papillotomy had healed (C), and hot-snare resection was used to resect the minor papilla without a saline lift (D); No residual adenomatous tissue was seen after minor papillectomy (E); and biopsies of the resection margins provided pathologic confirmation of complete resection. A PD stent was left at the conclusion of the procedure (F) and rectal indomethacin was administered.

- Citation: Gaspar JP, Stelow EB, Wang AY. Approach to the endoscopic resection of duodenal lesions. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(2): 600-617

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i2/600.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i2.600