Copyright

©2013 Baishideng Publishing Group Co.

World J Gastroenterol. May 21, 2013; 19(19): 2913-2920

Published online May 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i19.2913

Published online May 21, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i19.2913

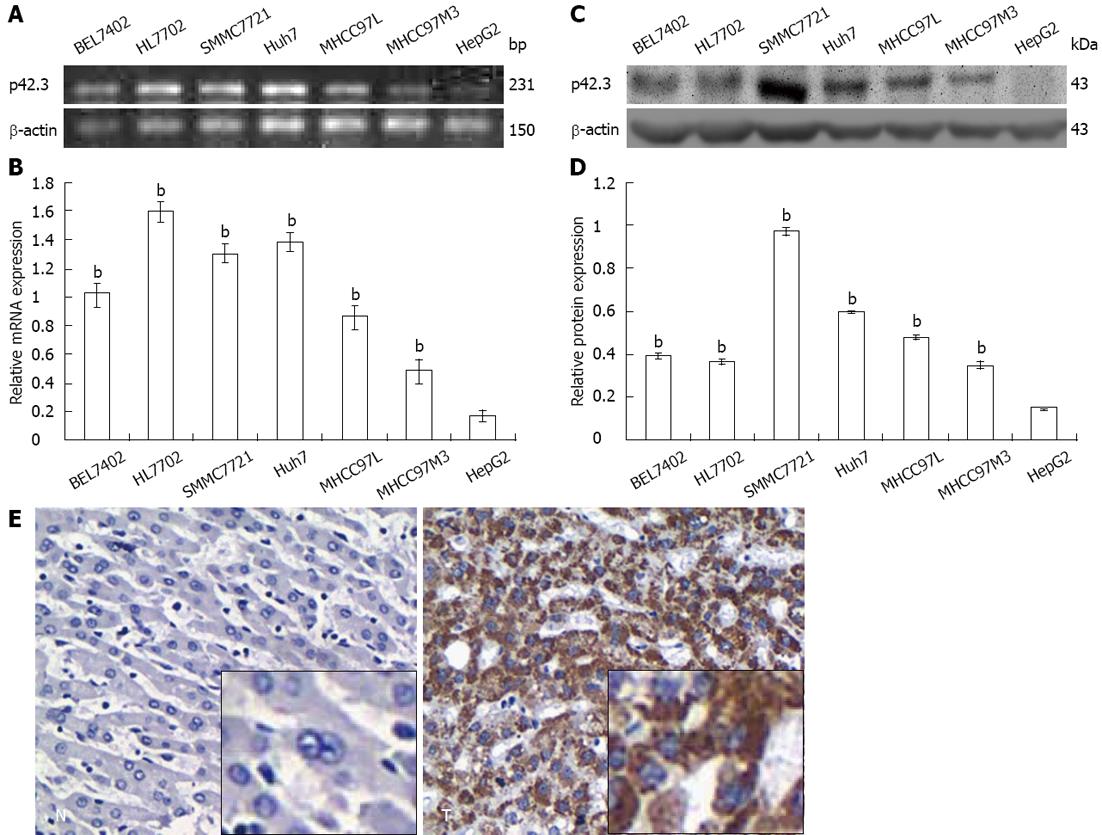

Figure 1 Detection of p42.

3 in hepatic cell lines and hepatocellular carcinoma tissues. A: Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis showed that p42.3 was detectable in all 7 cell lines, and the lowest expression was in HepG2 cells; B: Relative expression of p42.3 mRNA in seven hepatic cell lines using quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Data are shown as the mean ± SD, endogenous references was β-actin (bP < 0.01 vs HepG2); C and D: Expression of p42.3 protein in hepatic cell lines analyzed by Western blotting (C) and shown as mean ± SD (D) (bP < 0.01 vs HepG2); E: Negative staining of p42.3 in hepatocellular carcinoma-adjacent normal tissue (left), positive staining of p42.3 in tumor (right). Original magnification, × 100; the inset boxes are at original magnification × 200.

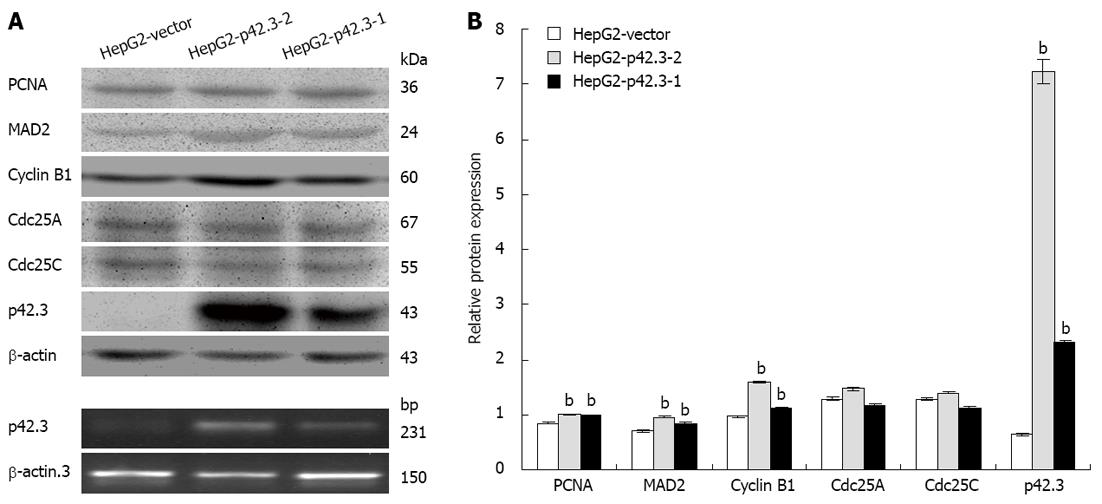

Figure 2 The effect on molecular by overexpression of p42.

3 in HepG2 cells. A: Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction and Western blotting were performed to confirm p42.3 overexpression in a stable single colony of HepG2-p42.3-1 and HepG2-p42.3-2 cells. p42.3 expression was deficient in the HepG2-vector control cells. β-actin served as an internal control; B: Expression of proteins shown as mean ± SD. Consistent with p42.3 protein expression, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), mitotic arrest deficient 2 (MAD2) and cyclin B1 expression were significantly upregulated. The protein levels of cell division cycle 25 A (Cdc25A) and cell division cycle 25 homolog C (Cdc25C) hardly changed following p42.3 expression (bP < 0.01 vs HepG2-vector).

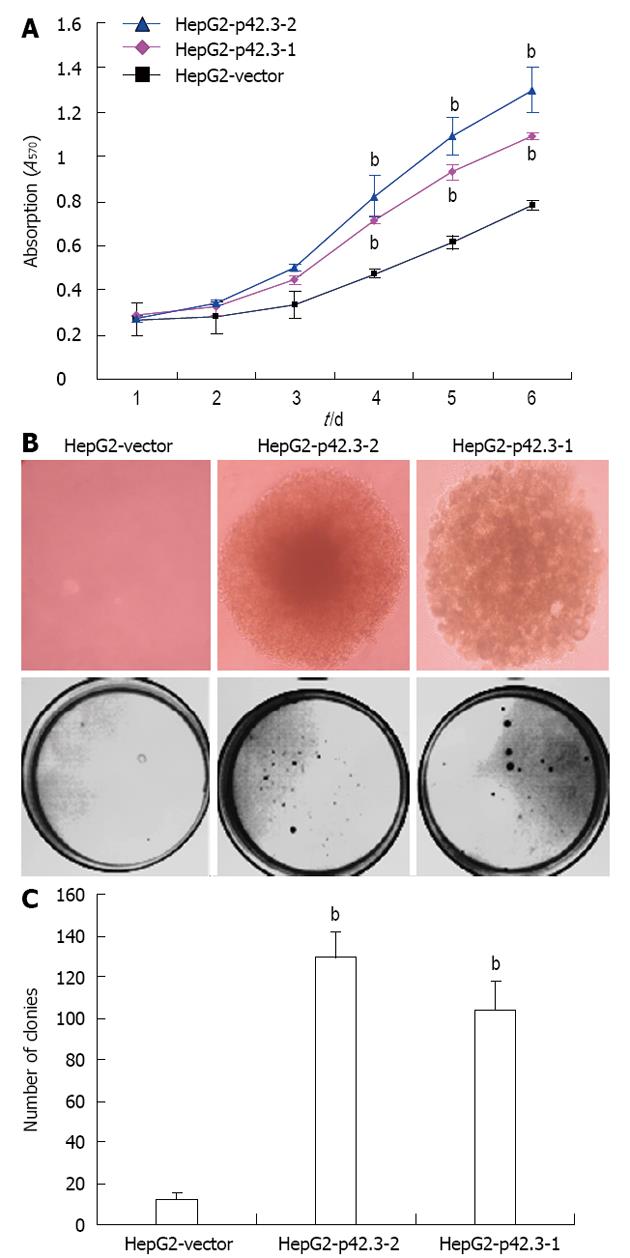

Figure 3 Promotion of cell growth and colony formation with p42.

3 overexpression in HepG2 cells. A: Promotion of cell growth after overexpression of p42.3 in HepG2. Growth curve comparing HepG2-p42.3-1, HepG2-p42.3-2, and HepG2-vector cells over a 6-d time course. Data are shown as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (bP < 0.01 vs HepG2-p42.3-1); B: The colonies of HepG2-p42.3-1, HepG2-p42.3-2, and HepG2-vector formed on soft agar. The colonies grew faster and were larger in HepG2 cells that overexpressed p42.3-2 than in the HepG2-vector control cells; C: Raw value indicating colony number. Data revealed that the colony-forming activities of HepG2-p42.3-1 and HepG2-p42.3-2 were significantly promoted on soft agar. The data represent the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (bP < 0.01 vs HepG2-vector).

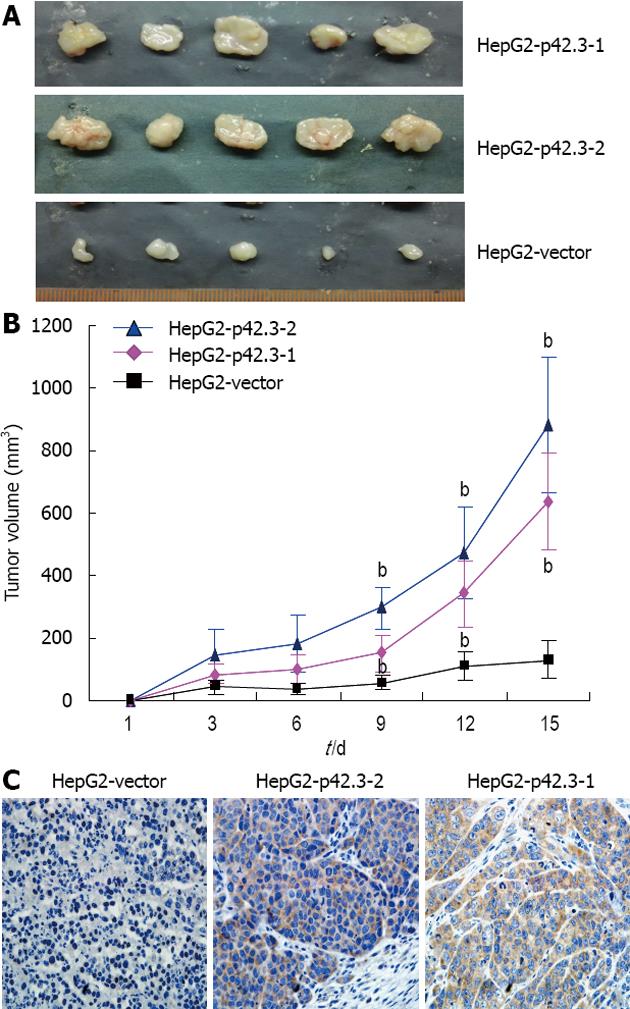

Figure 4 Promotion of tumorigenesis by overexpression of p42.

3 shows statistical significance compared with the control in HepG2 cells. A: The tumor induced by HepG2-p42.3-1 and HepG2-p42.3-2 was much larger than that in the control; B: Over the course of 15 d, the tumor growth curve comparing HepG2-p42.3-1, HepG2-p42.3-2, and HepG2-vector cells revealed that p42.3-overexpressing cells grew faster (bP < 0.01 vs HepG2-p42.3-1); C: Immunohistochemistry staining was performed in xenograft tissues from tumors. p42.3 protein was detectable in xenografts that were formed by injection of p42.3-overexpressing cells, but not in the tumors developed from HepG2-vector cells.

- Citation: Sun W, Dong WW, Mao LL, Li WM, Cui JT, Xing R, Lu YY. Overexpression of p42.3 promotes cell growth and tumorigenicity in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(19): 2913-2920

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i19/2913.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i19.2913