Published online Dec 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i46.8120

Peer-review started: October 13, 2017

First decision: October 30, 2017

Revised: November 10, 2017

Accepted: October 28, 2017

Article in press: November 28, 2017

Published online: December 14, 2017

The recent development of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) against hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection could lead to higher sustained virological response (SVR) rates, with shorter treatment durations and fewer adverse events compared with regimens that include interferon. However, a relatively small proportion of patients cannot achieve SVR in the first treatment, including DAAs with or without peginterferon and/or ribavirin. Although retreatment with a combination of DAAs should be conducted for these patients, it is more difficult to achieve SVR when retreating these patients because of resistance-associated substitutions (RASs) or treatment-emergent substitutions. In Japan, HCV genotype 1b (GT1b) is founded in 70% of HCV-infected individuals. In this minireview, we summarize the retreatment regimens and their SVR rates for HCV GT1b. It is important to avoid drugs that target the regions targeted by initial drugs, but next-generation combinations of DAAs, such as sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir for 12 wk or glecaprevir/pibrentasvir for 12 wk, are proposed to be potential solution for the HCV GT1b-infected patients with treatment failure, mainly on a basis of targeting distinctive regions. Clinicians should follow the new information and resources for DAAs and select the proper combination of DAAs for the retreatment of HCV GT1b-infected patients with treatment failure.

Core tip: In this minireview, we focused on the retreatment of patients with treatment failure of direct-acting antiviral agents against hepatitis C virus genotype 1b (HCV GT1b) infection. We summarized the retreatment regimens for patients with failure of peginterferon and ribavirin plus HCV NS3/4A inhibitors and for those with failure of HCV NS5A inhibitors. We also demonstrated the resistance-associated substitutions of HCV NS5B nucleos(t)ide inhibitors. Attention should be paid when selecting both the initial treatment and retreat regimens to completely eradicate HCV infection.

- Citation: Kanda T, Nirei K, Matsumoto N, Higuchi T, Nakamura H, Yamagami H, Matsuoka S, Moriyama M. Retreatment of patients with treatment failure of direct-acting antivirals: Focus on hepatitis C virus genotype 1b. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(46): 8120-8127

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i46/8120.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i46.8120

In the interferon era, the eradication of the hepatitis C virus (HCV) has had beneficial effects, such as the regression of liver fibrosis, hepatic decompensation, and the reduction of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in HCV-infected individuals[1]. Based on these results, in the direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) era, it also seems important to eradicate HCV to improve the prognosis of HCV-infected individuals.

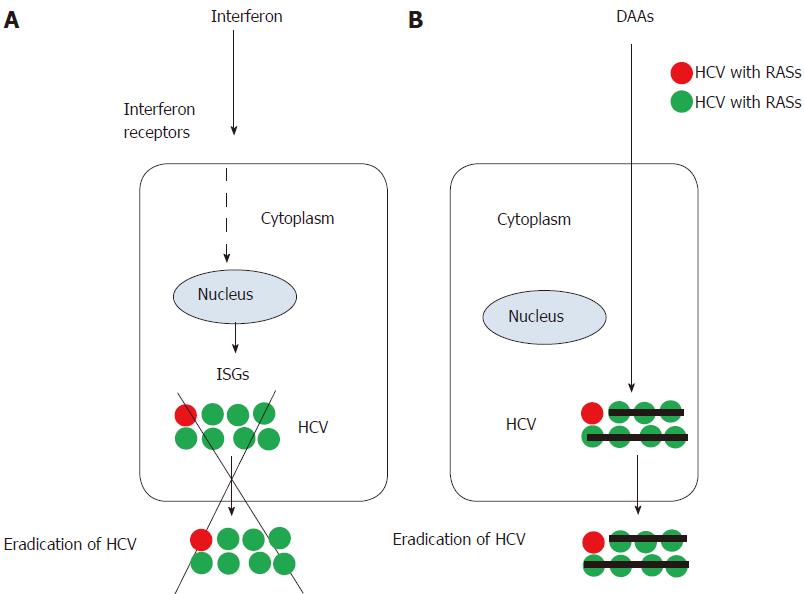

Interferon acts on the target cells, such as hepatocytes and/or lymphocytes through the interferon receptors on their surface and induces interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) and antiviral effects[2]. Almost all human cells have interferon receptors on their surfaces, and the use of interferon exhibits numerous adverse events. However, because interferon acts in a HCV-nonspecific manner, interferon can eradicate mutant viruses in most cases (Figure 1). The achievement of sustained virological response at week 24 after the end of treatment (SVR24) was strongly affected by single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) near the interleukin-28 B (IL28B)/interferon lambda 3-coding region in patients who were treated with peginterferon plus ribavirin, with or without DAAs[3-6].

HCV genome encodes at least 10 proteins: core, E1, E2, p7, NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A and NS5B[7]. In current DAA treatment for patients infected with HCV, viral proteins targeted by HCV DAAs are HCV NS3/4A, NS5A and/or NS5B. A combination of HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitors, HCV NS5A inhibitors and/or HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitors, with or without ribavirin, are currently available for the treatment of HCV-infected patients, according to their HCV genotypes (GTs)[7]. Until the appearance of HCV pan-genotypic DAA regimens, most of treatments had been HCV GT-specific regimens. Representative HCV pan-genotypic drugs are shown in Table 1.

| Target regions | DAAs | HCV GTs |

| NS3/4A | Glecaprevir | Pan-GTs |

| Grazoprevir | 1, 4 | |

| Asunaprevir | 1b | |

| Paritaprevir | 1, 2a, 4 | |

| Simeprevir | 1, 4 | |

| Telaprevir | 1, 2 | |

| Boceprevir | 1 | |

| NS5A | Pibrentasvir | Pan-GTs |

| Velpatasvir | Pan-GTs | |

| Elbasvir | Pan-GTs | |

| Daclatasvir | Pan-GTs | |

| Ledipasvir | 1, 4, 5 | |

| Ombitasvir | 1, 4 | |

| NS5B | Sofosbuvir [nucleos(t)ide inhibitor] | Pan-GTs |

| Dasabuvir [non-nucleos(t)ide inhibitor] | 1 |

The daily oral administration of DAAs does not require injection therapy. Interferon-free treatment acts directly on HCV in a HCV RNA genome-specific manner and has fewer adverse events than interferon treatment does(Figure 1)[8-10]. In interferon-era or interferon-free-era, respectively, SVR24 and SVR12 have been defined as SVR because DAA combination regimens have stronger effects. However, resistance-associated substitutions (RASs) in the HCV RNA genome at baseline reduce the efficacy of some DAA combination regimens[11-13]. It is well known that RASs in HCV genomes with treatment failure have significantly negative effects on the efficacy of retreatment with DAAs[14-16]. Ultra-deep sequencing has been used for the research purpose, but direct-sequencing method is applicable for the screening detection of RASs in daily clinical practice. When using DAA combinations, attention should be paid to the RASs and the drug-drug interactions.

Naturally occurring HCV variants depend on different geographic areas and they have some impacts on the context of current HCV therapy. Because of the high-prevalent infection of HCV GT1b in Japanese chronic hepatitis C patients, retreatment regimens of HCV GT1b is intensively discussed.

Using a combination of peginterferon and ribavirin plus protease inhibitors has led to approxiately 70% SVR rates in HCV GT1b-infected patients[6,17-22]. This combination including second generation protease inhibitors has fewer adverse events than do regimens including telaprevir or boceprevir, and it has similar SVR rates[6,22-25].

Among HCV GT1-infected Japanese patients, 98%-99% of these patients are infected with HCV GT1b[26]. D168N mutations were observed in only 1.1% (1/88) of HCV GT1b NS3/4A inhibitor-treatment-naïve patients[27]. In Japan, resistance mutations at the HCV NS3/4A regions are not always measured before treatment with a combination of peginterferon and ribavirin plus HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitors. During and after the use of HCV NS3/4A inhibitors, treatment failure occurs in HCV GT1a patients more often than it occurs in HCV GT1b patients. We have previously summarized the resistance mutations associated with resistance to HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitors[27].

The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)[28-31] has recommended a daily fixed-dose combination of sofosbuvir (400 mg)/HCV NS5A inhibitor velpatasvir (100 mg) for 12 wk, or a daily fixed-dose combination of HCV NS3/4A inhibitor glecaprevir (300 mg)/HCV NS5A inhibitor pibrentasvir (120 mg) for 12 wk, for the retreatment against HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitor with peginterferon and ribavirin-experienced, HCV GT1-patients with or without cirrhosis. They also recommended a daily fixed-dose combination of HCV NS5A inhibitor elbasvir (50 mg)/HCV NS3/4A inhibitor grazoprevir (100 mg) for 12 wk or a daily fixed-dose combination of HCV NS5A inhibitor ledipasvir (90 mg)/HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir (400 mg) for 12 wk in the retreatment for HCV GT1b patients with or without cirrhosis, respectively[28,29].

For HCV GT1 and non-cirrhotic/cirrhotic patients who were previously treated with peginterferon and ribavirin plus HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitors, a daily fixed-dose combination of ledipasvir (90 mg)/sofosbuvir (400 mg) with or without ribavirin for 12 and 24 wk led to SVR rates of 96.2% (50/52)/85.7% (12/14) or 100% (51/51)/84.6% (11/13) and 97.2% (35/36)/100% (14/14) or 100% (38/38)/100% (13/13), respectively[29]. In the retreatment of previous users of peginterferon plus ribavirin with HCV NS3/4A inhibitors, ledipasvir plus sofosbuvir should be selected as a first-line treatment[1,6,28]. We reported that 100% SVR rates (25/25) were achieved by 12 wk of combination treatment with ledipasvir plus sofosbuvir in patients previously treated with peginterferon plus ribavirin with various HCV NS3/4A inhibitors[6]. It may be important to avoid drugs that target the regions targeted by initial drugs.

For HCV GT1 and cirrhotic patients who were previously treated with peginterferon and ribavirin plus DAAs, a daily fixed-dose combination of sofosbuvir (400 mg)/velpatasvir (100 mg) for 12 wk led to 100% (48/48) SVR rates [100% (37/37) and 100% (11/11) in GT1a and GT1b patients, respectively][30]. Among those previously treated with HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitor-based therapy without HCV NS5A inhibitor exposure who were retreated with the daily fixed-dose combination of glecaprevir (300 mg)/pibrentasvir (120 mg) administered as three 100 mg/40 mg fixed-dose combination pills for 12 wk, the SVR12 rates were 92% (23/25)[31]. These next-generation combinations of DAAs are proposed to be potential solution for the HCV GT1b-infected patients with treatment failure, mainly on a basis of targeting distinctive regions.

The use of daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for HCV GT1b was ineffective for patients with pre-existent HCV NS5A RASs or simeprevir failure, regardless of fibrosis status[32]. If possible, retreatment without HCV NS3/4A inhibitors should be selected for HCV GT1b-infected patients with treatment failure of peginterferon and ribavirin plus HCV NS3/4A inhibitors[6,33].

HCV NS5A inhibitors, such as daclatasvir and ledipasvir, in combination with other DAAs against other regions of HCV, with or without peginterferon/ribavirin, could efficiently inhibit HCV replication, according to HCV GTs[34]. We have also reported the summary of resistance mutations associated with resistance to HCV NS5A inhibitors[34].

In Japan, daclatasvir plus HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitor asunaprevir was introduced for the treatment of chronic HCV GT1b infection in 2013[35]. Treatment with daclatasvir and asunaprevir after screening for HCV NS5A RASs is a relatively safe and effective treatment for HCV GT1b patients in Japan[36,37]. However, 85.3% (29/34) of the patients with virologic failure had RASs to both daclatasvir (predominantly HCV NS5A-L31M/V-Y93H) and asunaprevir (predominantly NS3-D168 variants) detected at failure[35]. Japanese clinicians used the combination regimens of ledipasvir plus sofosbuvir for 12 wk in daclatasvir/asunaprevir-failure patients, resulting in only 64%-70% SVR rates[14,15,38].

The prevalence of HCV NS5A RASs was significantly higher in daclatasvir/asunaprevir-failure patients at amino acid positions 24, 28, 30, 31, 32 and 93 than it was in daclatasvir/asunaprevir-treatment naïve patients[38]. The presence of HCV NS5A RAS at positions 31, 32, 92, and 93 significantly attenuated the efficacy of retreatment with ledipasvir plus sofosbuvir. Of importance, HCV NS5A RASs at these positions have a negative impact on the achievement of SVR.

Recently, more effective regimens for treatment-experienced patients with HCV NS5A inhibitors have appeared[28], although it was recommended that treatment-experienced patients with HCV NS5A inhibitors should check their RASs or wait before further treatment[1]. AASLD guidelines recommend the daily fixed-dose combination of sofosbuvir (400 mg)/velpatasvir (100 mg)/HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitor voxilaprevir (100 mg) for GT1 patients with or without cirrhosis[28] (See also next sections[39]).

There are two types of HCV NS5B polymerase inhibitors: nucleos(t)ide inhibitors and non-nucleoside inhibitors. Treatment regimens including sofosbuvir, which is a nucleoside analogue, achieved higher SVR rates. RASs associated with the use of sofosbuvir are shown in Table 2[40-44]. Although RASs are distributed in all domains of the HCV NS5B polymerase structure[45], the S282 is located at the fingers domain near the palm domain, and the C316 and V321 are both located at the palm domain[41,45]. Of note, ribavirin associated RASs T390I and F415Y are both located in the thumb domain of HCV NS5B polymerase[42]. It has been reported that RASs of non-nucleoside inhibitors are the following: C316N/Y, M414I/V/T, L419M/S. R422K, M423A/I/T/B, C445F, Y448H, Y452H, I482L, A486I/T, V494A, P495A/T, V499A, P496S, G554S, S556G and D559G, which are all located at the palm and thumb domains of HCV NS5B polymerase structure[42].

| Domains of HCV NS5B polymerase[45] | HCV genotypes (GTs) | Ref. | ||

| GT1 | GT1a | GT1b | ||

| Fingers domain (AA1-188, 226-287) | C14R | [40] | ||

| D61G | [40] | |||

| T77T/A | [41] | |||

| S96T | [42] | |||

| N142T | N142S | [40,42] | ||

| L159F | [40-44] | |||

| E237G | [40] | |||

| S282T | S282R | [40-42] | ||

| Palm domain (AA188-226, 287-371) | M289I/L | [42,44] | ||

| L314P | [40] | |||

| C316R | [41] | |||

| L320F | L320I/V | [40-42] | ||

| V321A | V321I | [40,42,43] | ||

| T344I | [40] | |||

| Thumb domain (AA371-530) | F415Y | [43] | ||

| E440G, E/G | [42] | |||

| S470G | [40] | |||

When treatment failure was observed in case where the first-generation HCV NS5A inhibitor plus nucleoside inhibitor such as sofosbuvir with or without ribavirin had been selected as an initial DAA treatment for HCV GT1 patients, HCV genome sequences often had HCV NS5A RASs. It has been reported in POLARIS-1 and POLARIS-4 studies that treatment with sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir for 12 wk could lead to 96% (253/263) and 98% (178/182) SVR rates, respectively, in HCV GTs1-6 patients who were previously treated with DAAs[39]. In POLARIS-1 and POLARIS-4 studies, respectively, SVR rates of 97% (146/150) and 97% (76/78), respectively, were achieved in HCV GT1-patients, by sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir for 12 wk[39]; 96% (97/101) and 98% (53/54) in HCV GT1a-patients; and 100% (45/45) and 96% (23/24) in HCV GT1b-patients[39]. Twelve weeks of treatment with a fixed-dose combination of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir was effective and well tolerated among patients with GT1 infection for whom a DAA-based regimen had previously failed[39,46].

Sergi et al[47] reviewed that there was the association between HCV GT1b and fulminant liver failure, although HCV is a rare cause of fulminant hepatitis in Japan[48]. Of their two HCV RNA-positive cases with evidence of HBV infection, one case had a real coinfection showing simultaneous detection of HBV DNA in serum and liver, while the other patient was a chronic HBV carrier, seropositive for HBsAg and anti-HBc IgG but negative for anti-HBc IgM and HBV DNA in liver tissue[47]. It has been reported that hepatitis B reactivation during or after the treatment of DAA for chronic hepatitis C[49]. Similar SVR rates seem to be achieved with DAAs in HCV/HBV co-infected patients[50,51]. However, nucleos(t)ide analogues for HBV should be added to DAA therapy for HCV when serum HBV DNA levels are elevated[1].

There is no doubt that new, more effective combinations of DAAs have appeared and will continue to appear in the retreatment of patients who have experienced treatment failure of DAAs. Clinicians should pay careful attention when selecting the initial treatment and retreatment regimens to completely eradicate HCV infection (Table 3).

| Patients | APASL (2016)[1] | AASLD (2017)[28] |

| GT1 | ||

| Peginterferon and ribavirin plus HCV NS3/4A inhibitors-failure non-cirrhotic patients | Sofosbuvir/ledipasvir 12 wk | Sofosbuvir/ledipasvir 12 wk |

| Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir 12 wk | ||

| Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir 12 wk | ||

| Peginterferon and ribavirin plus HCV NS3/4A inhibitors-failure compensated cirrhotic patients | Sofosbuvir/ledipasvir 12 wk | Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir 12 wk |

| Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir 12 wk | ||

| (For GT1b) Elbasvir/grazoprevir 12 wk | ||

| HCV NS5A inhibitors-failure non-cirrhotic patients | Wait | Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir 12 wk |

| HCV NS5A inhibitors-failure compensated cirrhotic patients | RAS check | Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir 12 wk |

| Non-NS5A inhibitor/ sofosbuvir-failure non-cirrhotic patients | N/A | Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir 12 wk |

| (For GT1a) | ||

| Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir 12 wk | ||

| (For GT1b) Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir 12 wk | ||

| Non-NS5A inhibitor/ sofosbuvir-failure compensated cirrhotic patients | N/A | Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir 12 wk |

| (For GT1a) | ||

| Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir 12 wk | ||

| (For GT1b) Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir 12 wk | ||

| GT2 | ||

| Sofosbuvir/ribavirin-failure patients | N/A | Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir 12 wk |

| Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir 12 wk | ||

| GT3 | ||

| DAA (including NS5A inhibitors) - failure patients | N/A | Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir 12 wk |

| (For NS5A inhibitor-failure) weight-based ribavirin is recommended | ||

| GT4 | ||

| DAA (including NS5A inhibitors) - failure patients | N/A | Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir 12 wk |

| GT5/GT6 | ||

| DAA (including NS5A inhibitors) - failure patients | N/A | Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir 12 wk |

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Pan Q, Said ZAN, Sergi CM, Tamori A, Yoshioka K S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Omata M, Kanda T, Wei L, Yu ML, Chuang WL, Ibrahim A, Lesmana CR, Sollano J, Kumar M, Jindal A. APASL consensus statements and recommendation on treatment of hepatitis C. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:702-726. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Sasaki R, Kanda T, Nakamoto S, Haga Y, Nakamura M, Yasui S, Jiang X, Wu S, Arai M, Yokosuka O. Natural interferon-beta treatment for patients with chronic hepatitis C in Japan. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:1125-1132. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, Simon JS, Shianna KV, Urban TJ, Heinzen EL, Qiu P, Bertelsen AH, Muir AJ. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature. 2009;461:399-401. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, Berg T, Weltman M, Abate ML, Bassendine M, Spengler U, Dore GJ, Powell E. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1100-1104. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, Kurosaki M, Matsuura K, Sakamoto N, Nakagawa M, Korenaga M, Hino K, Hige S. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1105-1109. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Kanda T, Nakamoto S, Sasaki R, Nakamura M, Yasui S, Haga Y, Ogasawara S, Tawada A, Arai M, Mikami S. Sustained Virologic Response at 24 Weeks after the End of Treatment Is a Better Predictor for Treatment Outcome in Real-World HCV-Infected Patients Treated by HCV NS3/4A Protease Inhibitors with Peginterferon plus Ribavirin. Int J Med Sci. 2016;13:310-315. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Kanda T, Imazeki F, Yokosuka O. New antiviral therapies for chronic hepatitis C. Hepatol Int. 2010;4:548-561. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Gane EJ, Roberts SK, Stedman CA, Angus PW, Ritchie B, Elston R, Ipe D, Morcos PN, Baher L, Najera I. Oral combination therapy with a nucleoside polymerase inhibitor (RG7128) and danoprevir for chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 infection (INFORM-1): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1467-1475. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Lawitz E, Poordad FF, Pang PS, Hyland RH, Ding X, Mo H, Symonds WT, McHutchison JG, Membreno FE. Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir fixed-dose combination with and without ribavirin in treatment-naive and previously treated patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus infection (LONESTAR): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:515-523. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Sulkowski M, Hezode C, Gerstoft J, Vierling JM, Mallolas J, Pol S, Kugelmas M, Murillo A, Weis N, Nahass R. Efficacy and safety of 8 weeks versus 12 weeks of treatment with grazoprevir (MK-5172) and elbasvir (MK-8742) with or without ribavirin in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 mono-infection and HIV/hepatitis C virus co-infection (C-WORTHY): a randomised, open-label phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2015;385:1087-1097. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Lok AS, Gardiner DF, Lawitz E, Martorell C, Everson GT, Ghalib R, Reindollar R, Rustgi V, McPhee F, Wind-Rotolo M. Preliminary study of two antiviral agents for hepatitis C genotype 1. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:216-224. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Karino Y, Toyota J, Ikeda K, Suzuki F, Chayama K, Kawakami Y, Ishikawa H, Watanabe H, Hernandez D, Yu F. Characterization of virologic escape in hepatitis C virus genotype 1b patients treated with the direct-acting antivirals daclatasvir and asunaprevir. J Hepatol. 2013;58:646-654. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Kumada H, Chayama K, Rodrigues L Jr, Suzuki F, Ikeda K, Toyoda H, Sato K, Karino Y, Matsuzaki Y, Kioka K, Setze C, Pilot-Matias T, Patwardhan M, Vilchez RA, Burroughs M, Redman R. Randomized phase 3 trial of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir for hepatitis C virus genotype 1b-infected Japanese patients with or without cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2015;62:1037-1046. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Akuta N, Sezaki H, Suzuki F, Fujiyama S, Kawamura Y, Hosaka T, Kobayashi M, Kobayashi M, Saitoh S, Suzuki Y. Ledipasvir plus sofosbuvir as salvage therapy for HCV genotype 1 failures to prior NS5A inhibitors regimens. J Med Virol. 2017;89:1248-1254. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Iio E, Shimada N, Takaguchi K, Senoh T, Eguchi Y, Atsukawa M, Tsubota A, Abe H, Kato K, Kusakabe A. Clinical evaluation of sofosbuvir/ledipasvir in patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 with and without prior daclatasvir/asunaprevir therapy. Hepatol Res. 2017;47:1308-1316. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Kawakami Y, Ochi H, Hayes CN, Imamura M, Tsuge M, Nakahara T, Katamura Y, Kohno H, Kohno H, Tsuji K. Efficacy and safety of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir with ribavirin in chronic hepatitis C patients who failed daclatasvir/asunaprevir therapy: pilot study. J Gastroenterol. 2017; Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Poordad F, McCone J Jr, Bacon BR, Bruno S, Manns MP, Sulkowski MS, Jacobson IM, Reddy KR, Goodman ZD, Boparai N, DiNubile MJ, Sniukiene V, Brass CA, Albrecht JK, Bronowicki JP; SPRINT-2 Investigators. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1195-1206. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, Marcellin P, Vierling JM, Zeuzem S, Poordad F, Goodman ZD, Sings HL, Boparai N. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1207-1217. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | McHutchison JG, Manns MP, Muir AJ, Terrault NA, Jacobson IM, Afdhal NH, Heathcote EJ, Zeuzem S, Reesink HW, Garg J. Telaprevir for previously treated chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1292-1303. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, Di Bisceglie AM, Reddy KR, Bzowej NH, Marcellin P, Muir AJ, Ferenci P, Flisiak R. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405-2416. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Zeuzem S, Andreone P, Pol S, Lawitz E, Diago M, Roberts S, Focaccia R, Younossi Z, Foster GR, Horban A. Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2417-2428. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Kanda T, Yokosuka O, Omata M. Faldaprevir for the treatment of hepatitis C. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:4985-4996. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | Manns M, Marcellin P, Poordad F, de Araujo ES, Buti M, Horsmans Y, Janczewska E, Villamil F, Scott J, Peeters M. Simeprevir with pegylated interferon alfa 2a or 2b plus ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection (QUEST-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;384:414-426. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Jacobson IM, Dore GJ, Foster GR, Fried MW, Radu M, Rafalsky VV, Moroz L, Craxi A, Peeters M, Lenz O. Simeprevir with pegylated interferon alfa 2a plus ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection (QUEST-1): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;384:403-413. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Kanda T, Nakamoto S, Wu S, Yokosuka O. New treatments for genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C - focus on simeprevir. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2014;10:387-394. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Wu S, Kanda T, Nakamoto S, Jiang X, Miyamura T, Nakatani SM, Ono SK, Takahashi-Nakaguchi A, Gonoi T, Yokosuka O. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus subgenotypes 1a and 1b in Japanese patients: ultra-deep sequencing analysis of HCV NS5B genotype-specific region. PLoS One. 2013;8:e73615. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Wu S, Kanda T, Nakamoto S, Imazeki F, Yokosuka O. Hepatitis C virus protease inhibitor-resistance mutations: our experience and review. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:8940-8948. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | AASLD HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C.Available from: http://www.hcvguidelines.org accessed on 2017/10/02. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Afdhal N, Reddy KR, Nelson DR, Lawitz E, Gordon SC, Schiff E, Nahass R, Ghalib R, Gitlin N, Herring R. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1483-1493. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Feld JJ, Jacobson IM, Hézode C, Asselah T, Ruane PJ, Gruener N, Abergel A, Mangia A, Lai CL, Chan HL. Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir for HCV Genotype 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2599-2607. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Poordad F, Felizarta F, Asatryan A, Sulkowski MS, Reindollar RW, Landis CS, Gordon SC, Flamm SL, Fried MW, Bernstein DE. Glecaprevir and pibrentasvir for 12 weeks for hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection and prior direct-acting antiviral treatment. Hepatology. 2017;66:389-397. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Ogawa E, Furusyo N, Yamashita N, Kawano A, Takahashi K, Dohmen K, Nakamuta M, Satoh T, Nomura H, Azuma K, Koyanagi T, Kotoh K, Shimoda S, Kajiwara E, Hayashi J; Kyushu University Liver Disease Study(KULDS) Group. Effectiveness and safety of daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1b aged 75 years and over with or without cirrhosis. Hepatol Res. 2017;47:E120-E131. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Bourlière M, Bronowicki JP, de Ledinghen V, Hézode C, Zoulim F, Mathurin P, Tran A, Larrey DG, Ratziu V, Alric L. Ledipasvir-sofosbuvir with or without ribavirin to treat patients with HCV genotype 1 infection and cirrhosis non-responsive to previous protease-inhibitor therapy: a randomised, double-blind, phase 2 trial (SIRIUS). Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:397-404. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Nakamoto S, Kanda T, Wu S, Shirasawa H, Yokosuka O. Hepatitis C virus NS5A inhibitors and drug resistance mutations. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:2902-2912. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Kumada H, Suzuki Y, Ikeda K, Toyota J, Karino Y, Chayama K, Kawakami Y, Ido A, Yamamoto K, Takaguchi K. Daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for chronic HCV genotype 1b infection. Hepatology. 2014;59:2083-2091. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Kanda T, Yasui S, Nakamura M, Suzuki E, Arai M, Haga Y, Sasaki R, Wu S, Nakamoto S, Imazeki F. Daclatasvir plus Asunaprevir Treatment for Real-World HCV Genotype 1-Infected Patients in Japan. Int J Med Sci. 2016;13:418-423. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 37. | Hirotsu Y, Kanda T, Matsumura H, Moriyama M, Yokosuka O, Omata M. HCV NS5A resistance-associated variants in a group of real-world Japanese patients chronically infected with HCV genotype 1b. Hepatol Int. 2015;9:424-430. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Kurosaki M, Itakura J, Higuchi M, Yasui Y, Tamaki N, Tsuchiya K, Izumi N. Real world experience of re-treatment by ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for patients who failed previous daclatasvir plus asunaprevir therapy: interim analysis from large scale nation-wide study. Hepatology. 2017;66 Suppl 1:579A. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Bourlière M, Gordon SC, Flamm SL, Cooper CL, Ramji A, Tong M, Ravendhran N, Vierling JM, Tran TT, Pianko S. Sofosbuvir, Velpatasvir, and Voxilaprevir for Previously Treated HCV Infection. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2134-2146. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 40. | Wyles D, Dvory-Sobol H, Svarovskaia ES, Doehle BP, Martin R, Afdhal NH, Kowdley KV, Lawitz E, Brainard DM, Miller MD. Post-treatment resistance analysis of hepatitis C virus from phase II and III clinical trials of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. J Hepatol. 2017;66:703-710. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 41. | Donaldson EF, Harrington PR, O’Rear JJ, Naeger LK. Clinical evidence and bioinformatics characterization of potential hepatitis C virus resistance pathways for sofosbuvir. Hepatology. 2015;61:56-65. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 42. | Sarrazin C, Dvory-Sobol H, Svarovskaia ES, Doehle BP, Pang PS, Chuang SM, Ma J, Ding X, Afdhal NH, Kowdley KV. Prevalence of Resistance-Associated Substitutions in HCV NS5A, NS5B, or NS3 and Outcomes of Treatment With Ledipasvir and Sofosbuvir. Gastroenterology. 2016;151:501-512.e1. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 43. | Kowdley KV, Gordon SC, Reddy KR, Rossaro L, Bernstein DE, Lawitz E, Shiffman ML, Schiff E, Ghalib R, Ryan M. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for 8 or 12 weeks for chronic HCV without cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1879-1888. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 44. | Svarovskaia ES, Dvory-Sobol H, Parkin N, Hebner C, Gontcharova V, Martin R, Ouyang W, Han B, Xu S, Ku K. Infrequent development of resistance in genotype 1-6 hepatitis C virus-infected subjects treated with sofosbuvir in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:1666-1674. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 45. | Mosley RT, Edwards TE, Murakami E, Lam AM, Grice RL, Du J, Sofia MJ, Furman PA, Otto MJ. Structure of hepatitis C virus polymerase in complex with primer-template RNA. J Virol. 2012;86:6503-6511. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 46. | Lawitz E, Poordad F, Wells J, Hyland RH, Yang Y, Dvory-Sobol H, Stamm LM, Brainard DM, McHutchison JG, Landaverde C. Sofosbuvir-velpatasvir-voxilaprevir with or without ribavirin in direct-acting antiviral-experienced patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2017;65:1803-1809. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 47. | Sergi C, Jundt K, Seipp S, Goeser T, Theilmann L, Otto G, Otto HF, Hofmann WJ. The distribution of HBV, HCV and HGV among livers with fulminant hepatic failure of different aetiology. J Hepatol. 1998;29:861-871. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 48. | Kanda T, Yokosuka O, Imazeki F, Saisho H. Acute hepatitis C virus infection, 1986-2001: a rare cause of fulminant hepatitis in Chiba, Japan. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:556-558. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 49. | Holmes JA, Yu ML, Chung RT. Hepatitis B reactivation during or after direct acting antiviral therapy - implication for susceptible individuals. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2017;16:651-672. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 50. | Wang C, Ji D, Chen J, Shao Q, Li B, Liu J, Wu V, Wong A, Wang Y, Zhang X. Hepatitis due to Reactivation of Hepatitis B Virus in Endemic Areas Among Patients With Hepatitis C Treated With Direct-acting Antiviral Agents. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:132-136. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 51. | Chen G, Wang C, Chen J, Ji D, Wang Y, Wu V, Karlberg J, Lau G. Hepatitis B reactivation in hepatitis B and C coinfected patients treated with antiviral agents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2017;66:13-26. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |