Published online Feb 28, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i8.1039

Revised: December 28, 2009

Accepted: January 4, 2010

Published online: February 28, 2010

Mucormycosis is a rare but invasive opportunistic fungal infection associated with a high mortality rate, and normally occurs in immunocompromised patients. In this report, we describe an immunocompetent patient suffering from hepatic mucormycosis secondary to adrenal mucormycosis, which masquerades as hilar cholangiocarcinoma. After surgical procedure and treatment with amphotericin B and itraconazole, the patient recovered well and had a 2-year infection-free survival. To our knowledge, this special clinical manifestation of hepatic infection as well as adrenal mucormycosis has not been reported to date. Meanwhile, this is the first case of an immunocompetent patient with both adrenal and hepatic mucormycosis who has been treated successfully.

- Citation: Li KW, Wen TF, Li GD. Hepatic mucormycosis mimicking hilar cholangiocarcinoma: A case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(8): 1039-1042

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i8/1039.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i8.1039

Mucormycosis caused by order mucorales[1,2], a ubiquitous saprophytic mold found in soil and organic matter worldwide, is a rare but invasive opportunistic fungal infection. The disease in humans is mainly limited to people with risk factors such as neutropenia[3-6], immune deficiencies[2-4,7,8], malignant disease[2-8], malnutrition[3,4], diabetes[2-8], trauma[2,6], organ transplantation[2-5,7], and iron overload[3-6]. The clinical infection due to mucorales includes rhinocerebral, pulmonary, cutaneous, gastrointestinal and disseminated diseases[3,5]. The first two are the most common diseases and all entities are associated with a high mortality rate[3]. To our knowledge, mucormycosis rarely involves liver, and hardly harms bile duct resulting in stenosis and cholestasis. This case report may present the first patient with adrenal mucormycosis in literature.

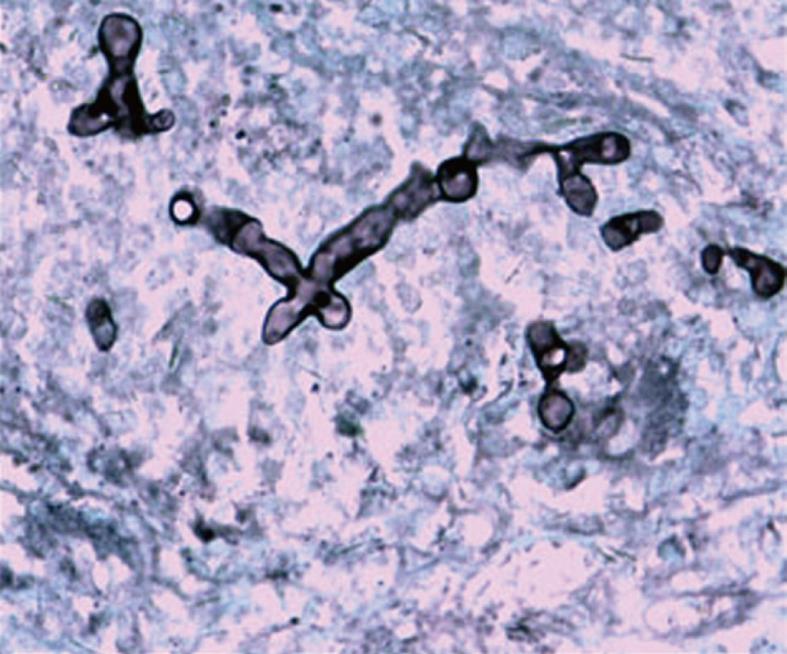

A 36-year-old man was referred for evaluation of abdominal pain and icterus in April 2007. He was admitted to our center with a 3-mo history of abdominal pain, and 4-d icterus. He had nonsymptomatic adrenal mucormycosis characterized by mass location in the right adrenal gland area 5 mo ago. At surgical exploration in previous hospitalization, the mass was identified to be tenacious, confusing with right adrenal gland and there was adhesion between mass and adjacent tissues. The patient underwent grossly total resection of the mass combined with the right adrenal gland immediately and mucormycosis infection was demonstrated histopathologically (Figure 1 and Figure 2A). Thus he was treated with itraconazole, 100 mg bid, for 1 mo. After his discharge, he was not followed up.

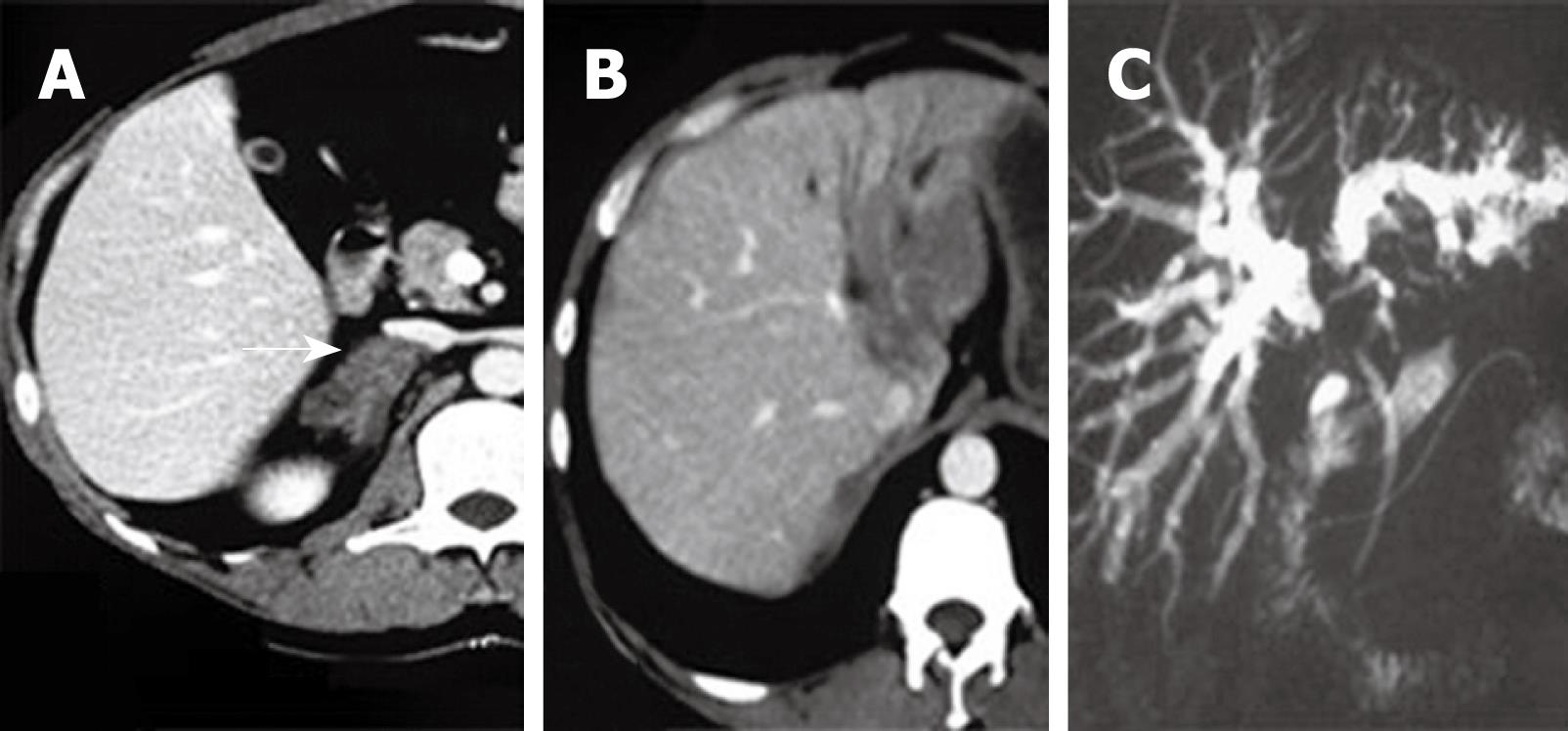

On physical examination at this second admission, his vital signs were normal and his abdomen was healthy. On investigation, his white blood cell count was 15 400/mm3 with 86.2% neutrophils. Liver function test showed a bilirubin of 78.9 IU/L; direct bilirubin, 54.2 IU/L; alanine transaminase, 463 IU/L (normal range, < 55 IU/L); alkaline phosphatase, 180 IU/L (normal range, < 45 IU/L); albumin, 43 g/L (normal range, 35-55 g/L); and CA19-9, 108.6 U/mL (normal range, < 22 IU/L). Viral hepatitis screening (including tests for hepatitis A, B and C) revealed infection of hepatitis B. Chest X-ray was unremarkable. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a lesion occupying the porta hepatis and partial left lateral lobe (Figure 2B); magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) demonstrated an abrupt stenosis of the primary biliary confluence with symmetric upstream dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts (Figure 2C). In light of initial evaluation, mucormycosis was suspected, but hilar cholangiocarcinoma (HCCA) could not be excluded.

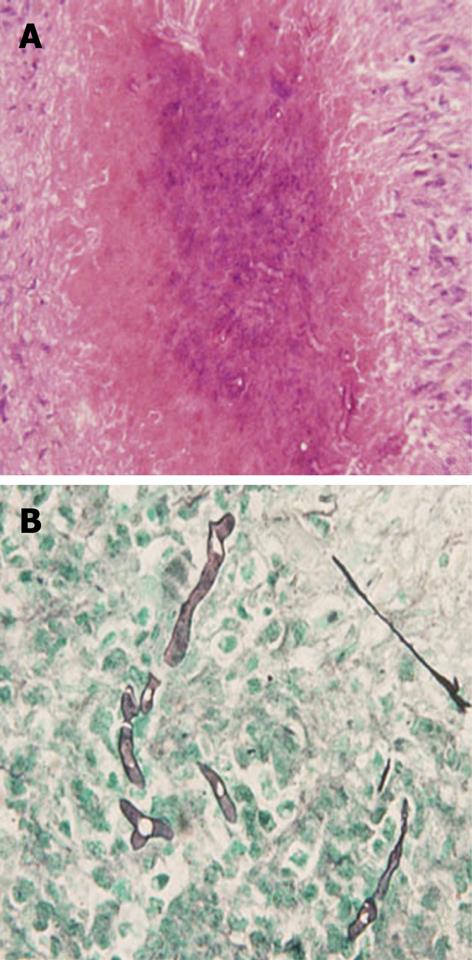

Therefore, an exploratory laparotomy was performed, revealed that the mass was yellowish-white and tenacious, with irregular but well-defined boundary, and no obvious necrotic center was detected. The sidewall of common hepatic duct became incrassate, forming a stenosis (nearly 3 mm of inside diameter) with dilatation and thickening of the intrahepatic bile ducts (Figure 3). It was unlike a malignant tumor grossly, hence partial resection of hepatic lesion for frozen section was achieved. Given the mucorales infection on the basis of intraoperative frozen section, we made a liver debridement to the fullest extent possible and placed a T-tube stent for 3 mo. Histopathologically, the liver was necrotic, in which extensive fungal proliferations were examined. Hematoxylin and eosin (HE), and grocott methenamine sliver (GMS) stains showed irregularly shaped broad nonseptate hyphae with the right angle branching typical of mucormycosis (Figure 4A and B). Intraoperative bile culture was performed but failed. Treatment with liposomal amphotericin B was initiated. Up to July 2007, he had received a cumulative 3 g of amphotericin B during the 3-mo hospitalization period. The patient was discharged in good general condition with an intraconazole prescription (100 mg bid for 4 mo). At this time, 2 years later, the patient remains alive and well. Abdominal MRI shows no evidence of the previous lesions.

Mucormycosis is a rare fungal infection. It represents 12% of all documented filamentous mycosis observed in the participating centers during the same period (Pagano et al[4], 1993). Portals of entry for mucorales include sinuses, lungs, gastrointestinal tract and skin. In the present cohort, none of disseminated cases involves the sinuses. In contrast, they involve the lungs and/or the gastrointestinal tract[9]. Hepatic involvement is commonly presented with pulmonary or gastrointestinal infection and is considered a part of the disseminated disease[3,7]. Disseminated mucormycosis is the most severe form and is said to be uniformly fatal[8]. It is reported that the diagnosis is made ante mortem in only 12 of 185 patients[10]. The time lost before a correct diagnosis is made may be critical for survival.

Our case presented a typical hypodense mass lesion in CT findings. The hypodense hepatic lesion surrounding vessels without a mass effect (Figure 2B) suggest an angioinvasive organism causing fungal thrombosis and involvement of perivascular area subsequently. The CT findings are not pathognomonic but are valuable in narrowing the differential diagnosis[8]. Also MRI could reveal correspondences of abnormalities. MRCP demonstrated an abrupt stenosis of the primary biliary confluence with symmetric upstream dilation of the intrahepatic bile ducts, mimicking HCCA.

Differentiating mucormycosis from HCCA is important because of the differences in treatment. On imaging, obstruction at the hepatic duct confluence is generally due to HCCA. However, in up to 15% of patients, hilar obstruction could be caused by alternative diagnoses other than HCCA[11,12]. Involvement of second-order bile ducts is rare in patients with benign lesions, and was observed in only 26% of patients with HCCA-potentially helpful diagnostically in only a small proportion of cases. By contrast, vascular invasion and lobar atrophy are both common findings in patients with HCCA and significantly more common than in patients with benign lesions[11]. However, imaging ability to accurately distinguish HCCA from alternative diagnoses is limited. In addition, of the patients with benign lesions, 33% had elevated tumor markers (carcinoembryonic antigen and CA 19-9) (Jonathan Koea et al[12]).

With regard to this case, culture and pathologic examinations of biopsy specimen provided the only definite diagnoses of mucormycosis. Mucorales appears in tissue as irregularly shaped, broad nonseptate hyphae with the right angle branching. The most characteristic features are perivascular and blood vessel invasions that result in arterial thrombosis and subsequent necrosis[3,9]. In our case, the sidewall of common hepatic duct became incrassate, forming a stenosis with upstream dilatation and thickening of the intrahepatic bile ducts, mimicking HCCA as the operation specimen and imaging represent. It suggested that the mucormycosis could likewise involve the bile ducts, leading to inflammation and incrassation of bile ducts. It has come to our knowledge that this characteristic has never been mentioned in the published series before.

Besides liver, there was also an adrenal gland involvement (primary infection), with no participation of the lung or other sites. As far as we know, involvement of the adrenal gland has not been described in the literature before, yet involvement of the brain, lung, kidney, stomach, colon, liver, spleen, thyroid gland, pancreas, and lymph nodes is known from autopsy[8]. However, the most initial portal of the infection remains unknown and deserves our attention.

The standard therapy for invasive mucormycosis is a combined medical-surgical approach[2,4,5,13]. High doses of amphotericin B should be used, rapidly reaching 1.0 mg/kg daily. Prolonged courses (> 6 wk) of amphotericin B are recommended, with total doses ranging between 1.5 and 3.0 g, according to the patient’s underlying conditions[13]. Our patient underwent subtotal liver resection and received a cumulative 3 g of liposomal amphotericin B, and well responded to the treatment. Additionally, T-tube stent and intraconazole played an important part in the treatment.

In conclusion, this case report illustrates a new form of clinical spectrum of mucormycosis. The successful treatment can be attributed to an early accurate diagnosis, anti-fungal therapy consisting of liposomal amphotericin B and intraconazole, as well as surgical debridement. As mentioned above, a therapeutic effect of T-tube stent cannot be excluded.

Peer reviewers: Salvatore Gruttadauria, MD, Assistant Professor, Abdominal Transplant Surgery, ISMETT, Via E. Tricomi, 190127 Palermo, Italy; Giuseppe Orlando, MD, PhD, Department of Health Sciences, Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine, 391 Technology Way, Winston Salem, NC 27101, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Lin YP

| 1. | Tsaousis G, Koutsouri A, Gatsiou C, Paniara O, Peppas C, Chalevelakis G. Liver and brain mucormycosis in a diabetic patient type II successfully treated with liposomial amphotericin B. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000;32:335-337. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Mazza D, Gugenheim J, Baldini E, Mouiel J. Gastrointestinal mucormycosis and liver transplantation; a case report and review of the literature. Transpl Int. 1999;12:297-298. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Suh IW, Park CS, Lee MS, Lee JH, Chang MS, Woo JH, Lee IC, Ryu JS. Hepatic and small bowel mucormycosis after chemotherapy in a patient with acute lymphocytic leukemia. J Korean Med Sci. 2000;15:351-354. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Pagano L, Ricci P, Tonso A, Nosari A, Cudillo L, Montillo M, Cenacchi A, Pacilli L, Fabbiano F, Del Favero A. Mucormycosis in patients with haematological malignancies: a retrospective clinical study of 37 cases. GIMEMA Infection Program (Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche Maligne dell'Adulto). Br J Haematol. 1997;99:331-336. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Jiménez C, Lumbreras C, Aguado JM, Loinaz C, Paseiro G, Andrés A, Morales JM, Sánchez G, García I, del Palacio A. Successful treatment of mucor infection after liver or pancreas-kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;73:476-480. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Uçkay I, Chalandon Y, Sartoretti P, Rohner P, Berney T, Hadaya K, van Delden C. Invasive zygomycosis in transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2007;21:577-582. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Oliver MR, Van Voorhis WC, Boeckh M, Mattson D, Bowden RA. Hepatic mucormycosis in a bone marrow transplant recipient who ingested naturopathic medicine. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:521-524. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Hagspiel KD, Kempf W, Hailemariam S, Marincek B. Mucormycosis of the liver: CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:340-342. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Almyroudis NG, Sutton DA, Linden P, Rinaldi MG, Fung J, Kusne S. Zygomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients in a tertiary transplant center and review of the literature. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:2365-2374. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Ingram CW, Sennesh J, Cooper JN, Perfect JR. Disseminated zygomycosis: report of four cases and review. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:741-754. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Are C, Gonen M, D'Angelica M, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Blumgart LH, Jarnagin WR. Differential diagnosis of proximal biliary obstruction. Surgery. 2006;140:756-763. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Koea J, Holden A, Chau K, McCall J. Differential diagnosis of stenosing lesions at the hepatic hilus. World J Surg. 2004;28:466-470. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Marcó del Pont J, De Cicco L, Gallo G, Llera J, De Santibanez E, D'agostino D. Hepatic arterial thrombosis due to Mucor species in a child following orthotopic liver transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2000;2:33-35. [Cited in This Article: ] |