Published online Jul 20, 2022. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v12.i4.285

Peer-review started: February 9, 2022

First decision: April 12, 2022

Revised: May 19, 2022

Accepted: July 11, 2022

Article in press: July 11, 2022

Published online: July 20, 2022

Processing time: 160 Days and 20.2 Hours

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has posed obstacles to the delivery of diabetic foot care. In response to this remote healthcare services have been deployed offering monitoring, follow-up, and referral services to patients with diabetic foot ulcers and related conditions. Although, remote diabetic foot care has been studied before the COVID-19 pandemic as an alternative to in-person care, the peculiar situation of the pandemic, which dictates that remote care would be the sole available option for healthcare practitioners and patients, necessitates an evaluation of the relevant knowledge obtained since the beginning of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 outbreak.

To perform a thorough search in PubMed/Medline and Cochrane to identify original records on the topic.

To identify relevant peer-reviewed publications and gray literature, the authors searched PubMed-MEDLINE and Cochrane Library-Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials starting September 27 till October 31, 2021. The reference lists of the selected sources and relevant systematic reviews were also hand–searched to identify potentially relevant resources. Otherwise, the authors searched Reference Citation Analysis (https://www.referencecitationanalysis.com/).

A number of randomized prospective studies, case series, and case reports have shown that the effectiveness of remote care is comparable to in-person care in terms of hospitalizations, amputations, and mortality. The level of satisfaction of patients’ receiving this type of care was high. The cost of remote healthcare was not significantly lower than in - person care though.

It is noteworthy that remote care during the COVID-19 pandemic appeared to be more effective and well - received than remote care in the past. Nevertheless, larger studies spanning over longer time intervals are necessary in order to validate these results and provide additional insights.

Core Tip: Telehealth has a major potential to sustain and improve diabetic foot care during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Studies reporting the experience of healthcare providers and patients around the globe are encouraging. These findings need to be validated with larger and long – term studies. In the post COVID era, the knowledge and experience obtained can serve as the standpoint of a hybrid approach of telemedicine and in-person care oriented towards delivering fast, efficient and cost-effective care to the patients.

- Citation: Kamaratos-Sevdalis N, Kamaratos A, Papadakis M, Tsagkaris C. Telehealth has comparable outcomes to in-person diabetic foot care during the COVID-19 pandemic. World J Methodol 2022; 12(4): 285-292

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v12/i4/285.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v12.i4.285

During the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, access to healthcare has been hampered by restrictions on citizen movement applied by governments globally as well as people in vulnerable demographics avoiding or delaying visiting healthcare facilities due to health concerns. Internal hospital rearrangements in order to prioritize COVID-19-centered care, especially relevant from our experience in the Diabetes Center of Tzaneio General Hospital of Piraeus in Greece, result in debilitation of the health systems’ capacity to assess patients in need in a timely manner[1]. Patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) have been greatly affected by this. In addition to being a high-risk group, they need to consult their treating physicians often to maintain DM and its complications under control[2]. This need has remained unmet on many occasions. The repercussions of this have been evident particularly with regard to diabetic foot ulcerations, where lockdown periods have been followed by an increased rate of emergency hospitalizations and limb amputations[3].

Diabetic foot (DF), as defined by the International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot, is infection, ulceration or destruction of tissues of the foot associated with neuropathy and/or peripheral artery disease in the lower extremity of a person with (a history of) diabetes mellitus[4]. On a global scale, according to Global Burden of Disease an estimate of 131 million (1.8% of the population) people had developed a diabetes related lower extremity complication, chief among them being foot ulcers[5]. DF amounts for a significant amount of healthcare spending, as it is estimated to account for one third of diabetes spending which was $237 billion in 2017 in the United States, increasing by 26% from 2012[6,7]. As a result, this is a disease which rivals cancer cost ($80.2B in 2015)[7]. We should also take into account indirect costs which include absenteeism from work or reduced productivity and even early mortality, which accounted for $90B[8].

While DF is one of the many diabetes sequelae, it is the one responsible for the most hospitalizations[5]. All diabetic patients have been estimated to have a 25% risk of developing a DF ulcer, with type 2 diabetics having a slightly higher chance[9,10]. Almost 50% of them are expected to become infected and in moderate to severe cases of infection about 20% will require to be amputated[11]. In fact, diabetes dominates nontraumatic lower extremity amputations, accounting for 85% of these operations.

To better understand the challenges of providing appropriate care and preventing amputations in patients with DF, one should consider this condition as a culmination of vascular disease, neuropathy and oftentimes disrupted immunity, vision impairment, debilitating comorbid conditions and frailty[12]. DF care requires frequent visualization, measurement and assessment of the wound by a specialist in addition to diverse treatment strategies including the use of medications, debridement patches and surgical cleaning of the wound. Having all this in mind, we can see how limited healthcare access directly affects the care of these individuals. The potential of remote care to patients unable to access healthcare facilities to stave off this highly morbid disease has been acknowledged before the pandemic. During the pandemic, the need to decrease the DF related burden of secondary and tertiary healthcare facilities, prevent hospitalizations and protect the patients from life-changing complications became even more evident. Although there is abundant research about remote diabetes care before and during the pandemic, there is limited evidence focusing specifically on DF care under these circumstances.

The authors summarize primary research focusing on digital health and remote care for DF, its precipitating factors and sequelae and identify relevant research gaps and fields of action.

To identify relevant peer-reviewed publications and gray literature, the authors searched PubMed-Medline and Cochrane Library-Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials starting September 27 till October 31, 2021. The reference lists of the selected sources and relevant systematic reviews were also hand–searched to identify potentially relevant resources. Otherwise, the authors searched Reference Citation Analysis (https://www.referencecitationanalysis.com/). The search terms: (“Digital health” OR “Remote Healthcare” OR “Telemedicine”) AND (“Diabetic Foot”[MeSH] OR “Diabetic Angiopathies”[MeSH] OR “Foot Ulcer [MeSH]” OR "Diabetic Neuropathies"[MeSH]) AND "COVID-19"[MeSH] were used. Studies were included if they fulfilled all the following eligibility criteria: (1) Ongoing or published clinical studies reporting on digital and remote healthcare applications in the prevention or management of DF, its risk factors and sequelae; and (2) Epidemiological analyses and reports. A study was excluded if it met at least one of the following criteria: (1) Non-English publication language; and (2) Study types: editorials, opinion articles, perspectives, letters to the editor. No sample size restriction was applied when screening for eligible studies. Disputes in the selection of relevant studies were discussed between the two primary authors and a senior author until a consensus was reached. The literature was searched and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews.

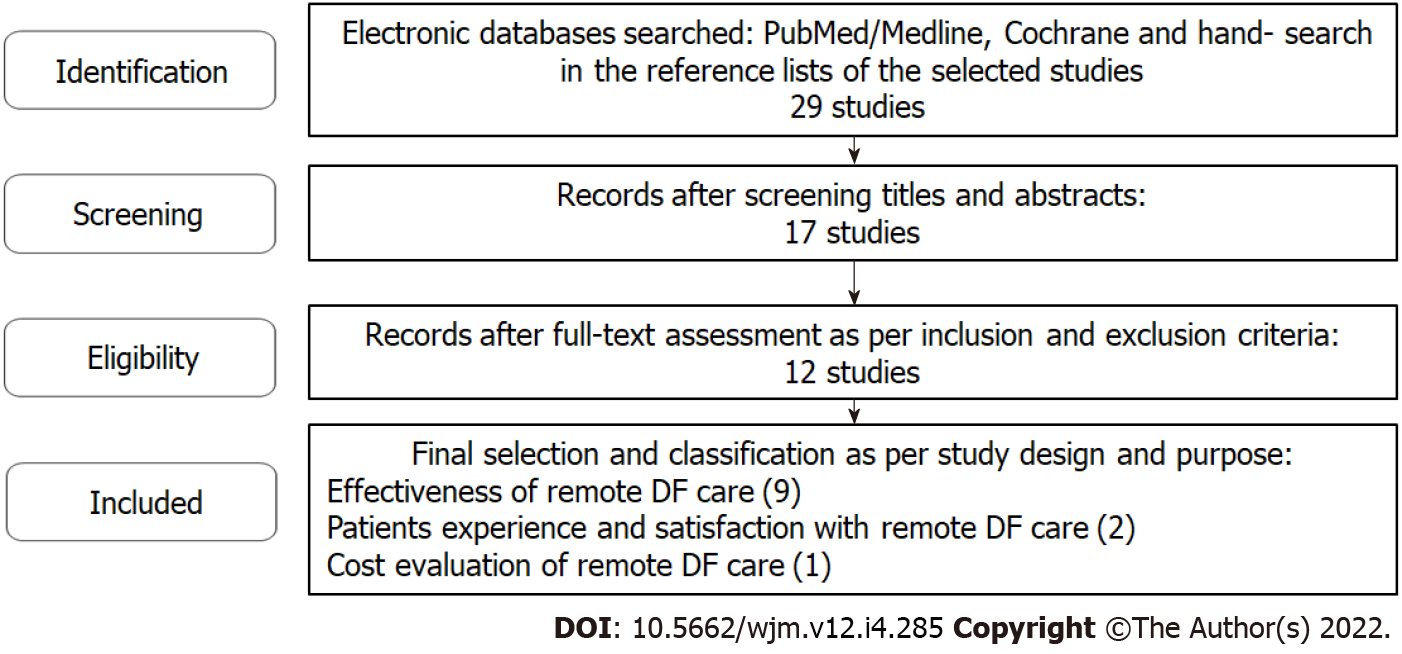

The initial search yielded 29 relevant publications, following the exclusion of non - primary sources from the database search and the deletion of duplicates. After screening titles and abstracts (n = 29) and excluding 12 records on the grounds of irrelevance to the topic, the full texts of 17 articles were assessed. Twelve studies were eventually included in the present review (Figure 1).

A detailed overview of the included studies’ characteristics is presented in Table 1.

| Ref. | Country | Study type | Objective of the study | Sample size | Key outcomes |

| Rastogi et al[13] | India, United Kingdom | Observational cohort | Virtual monitoring of DF complications during COVID-19 | 1199 | Virtual healthcare has similar ulcer/limb outcomes as face-to-face care |

| Shankhdhar et al[16] | India | Case report | DF amputation prevention via telemedicine | 1 | Complete healing was achieved in 4 wk |

| Rasmussen et al[19] | Randomized controlled trial | Comparison between outpatient vs telemedical monitoring in DFU | 401 | Similar healing, amputation rates between both groups, higher mortality in telemedicine | |

| Kilic et al[22] | Turkey | Randomized prospective | Developing and evaluating a mobile foot care application for persons with DM | 88 | Both groups increased knowledge (test group significantly more so), behavior, and self-efficacy |

| Téot et al[14] | France | Randomized Control Trial | Complex Wound Healing Outcomes for Outpatients Receiving Care via Telemedicine, Home Health, or Wound Clinic | 173 | Healing time marginally faster for in-person patients. Mortality comparable |

| Iacopi et al[23] | Italy | Survey | A survey on patients' perception of a telemedicine service for DF | 206 | Patients thought telemonitoring to be useful during and after the pandemic. Pts with complications worry more about DF than COVID-19 |

| Kavitha et al[17] | India | Case Reports | Application of tele-podiatry in diabetic foot management | 3 | Telemedicine effective in low-risk cases of DFU and for referral of higher-risk. Also effective for follow up |

| Ratliff et al[18] | United States | Case Reports | Telehealth for Wound Management During the COVID-19 Pandemic | 2 | Improved healing outcomes with implemented telemedicine |

| Meloni et al[15] | Italy | Cohort | Management of DFU during COVID-19: Effectiveness of a new triage pathway | 151 | Effective telemedical care with negated hospital transmission |

| Fasterholdt et al[24] | Denmark | Randomized Control Trial | Cost-effectiveness of telemonitoring of diabetic foot ulcer patients | 374 | Telemedicine cost is €2039 less per patient treated vs standard care; not statistically significant. Amputation rates were similar |

| Smith-Strøm et al[21] | Norway | Cluster Randomized Control Trial | Effect of Telemedicine Follow-up Care on Diabetes-Related Foot Ulcers | 182 | No significant difference in healing time, deaths, number of consultations, or patient satisfaction between standard care vs telemedicine. TM group had significantly fewer amputations |

| van Netten et al[20] | Australia | Cohort | The validity and reliability of remote diabetic foot ulcer assessment using mobile phone images | 50 | Mobile phone images should not be used as a stand-alone diagnostic instrument for remote assessment of diabetic foot ulcers due to low reliability |

Eight clinical studies reported on the utilization of telehealth services during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, Europe, the United Kingdom, Turkey and India (2020-2021). Four clinical studies with similar design and outcomes that were conducted before the pandemic were included. These studies serve as control when compared to studies conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of the studies presented observational data from cohorts, case series or sole case reports, fewer studies were designed as randomized clinical trials and one was based on a cross sectional survey. The existing evidence focused on the effectiveness of remote DF care and touched upon patients’ experience and satisfaction and cost evaluation

Studies regarding the effectiveness of various models of remote DF care during the COVID-19 pandemic paint a mostly positive picture. Utilizing a regime of virtual triage and consultations for a group of patients and comparing the outcomes with standard care from before the pandemic, Rastogi et al[13] concluded similar ulcer and limb outcomes in both groups, in a total of 1199 patients. In a randomized control trial (RCT) by Téot et al[14] in France that examined 173 patients, healing was insignificantly slower in the telehealth group, while both groups showed similar mortality rates. In an observational cohort study in Italy, Meloni et al[15] found telemedical care to be similarly as effective as outpatient care, while neutralizing healthcare setting transmission risk of COVID-19. Moving on to smaller scale studies, case report studies by Shankhdhar et al[16], Kavitha et al[17] and Ratliff et al[18], in India, India and United States respectively, report a positive healing outcome in an ulcer treated exclusively with telemedicine, effective assessment and follow-up of lower risk diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) cases and enhanced healing outcomes with telemedicine utilization respectively. Examining pre-pandemic literature on this topic we can derive that during recent years there has been a rise in interest in modernizing DFU care, although not without some potentially concerning findings. Interestingly studies before the pandemic report higher mortality in telehealth or inadequacy of remote care means like mobile photos - e.g., Rasmussen et al[19]; van Netten et al[20]. In an RCT by Rasmussen et al[19] in 2015, comparing outpatient vs telemedical monitoring in DFU, similar healing and amputation rates were found in both groups of 401 patients, but with an inexplicable higher mortality rate in the second group. van Netten et al[20], while observing a cohort of 50 patients regarding the reliability of DFU ulcer using mobile phone images concluded it to be an unreliable method of remote assessment. Finally, standard medicine was found comparable to telemedicine in terms of outcome and patient satisfaction in a cluster RCT in Norway by Smith-Strøm et al[21], and notably, there were significantly less amputations in the telemedicine group.

As with any implementation in healthcare, it is of vital importance to gauge patient experience and perception. In a randomized pilot study in Turkey by Kilic et al[22], a novel mobile application was developed as a way for patients to submit their blood glucose measurements and potentially pictures as well. This was compared to receiving 30 min of training once by a healthcare professional. After 6 mo, patient education and behavior had improved, and overall increased self-efficacy was found. Patients reported, in their majority, that they appreciated this portal of communication with the specialists and overall thought this was an effective contribution to their DFU care. In another similar study by Iacopi et al[23] in Italy, 206 patients’ opinions regarding their telemedicine consultations for DFU during the pandemic were assessed, as well as their anxiety regarding both COVID-19 and DFU. Patients were found to be very positive about their experience with telemedicine, finding it both very useful and a potential modality to keep using after the experiment. DFU patients seemed to be significantly more anxious regarding their existing DF disease compared to COVID-19, a result that was more apparent in the subgroup of patients with a history of ulceration, and even more prevalent in a subgroup that had undergone amputation. Regarding cost-effectiveness evaluation, in a study by Fasterholdt et al[24], the telemedical approach to treatment and monitoring of DFUs was not statistically significantly cheaper, although being cheaper by 2039 euros per patient. Some limitations of this study are the fact that it was conducted in Denmark in a highly urban setting which reasonably translates to a smaller distance between the patient’s setting and the care center in comparison to more rural areas. Furthermore, it did not take into account costs regarding personnel training and telemedicine implementation that would be required in order to apply this remote care modality.

Overall, available evidence suggests that remote DFU care has approximately similar or better outcomes to standard therapy regarding healing time and amputations. There is potential in utilizing telehealth methods in order to triage and consult patients without inconveniencing them with unnecessary and potentially hazardous trips to the physician’s office. In the study from Rasmussen et al[19] it was concerning that mortality was statistically significantly higher in the telehealth group, but without a concrete accountable reason, more large-scale studies are needed to justify this result. Finally, patients seemed to be content with telehealth applications, can recognize their usefulness and would be open to adding a telehealth element to their treatment regime. It is unfortunate that evidence regarding patient satisfaction is scarce up to this point, but with a more patient-centered healthcare approach undertaken globally, it would be reasonable to expect additional literature in the upcoming years.

Overall, it appears that telehealth services for DF remote care during the COVID-19 pandemic have been described in a number of studies, primarily during the first months of 2020. Remote DF care had already been developed before the pandemic, but its use was limited. This can be linked to studies showing increased mortality among telehealth services recipients[19]. It seems that remote DF care during the COVID-19 pandemic became more effective than before, as shown in a study done in Australia examining the adherence to national DF guidelines and treatment efficacy using telemedicine[25]. This can be attributed to the accumulated knowledge that helped physicians to avoid mistakes of the past, to the increased familiarization of physicians, patients and caregivers with telehealth during the last two years and to the relatively short - term monitoring time of the studies in comparison with previous research. Perhaps, monitoring these patients for a longer time would still reveal adverse outcomes that have not become evident to date. This interpretation is subject to a number of factors.

Firstly, one should acknowledge the geographical variation scarcity of the literature. Studies that we reviewed come from Europe (Norway, Denmark, Italy, France, United Kingdom), United States, India and Turkey. Suffice it to say that there’s a whole unknown world out there in terms of research on this subject, with large geographical regions not being represented as is. There is no literature regarding regions such as South America, Russia, Central Asia, Asia-Pacific and Africa, among others which inevitably lead to some level of bias. For example, the studies were done in countries and people that had access to remote healthcare services. This is best exemplified by the example of some developing countries, where it’s estimated that about one third of the population has access to the internet, the principal foundation of telehealth in DFU. In addition, even in more developed countries there is often a shortage of tech-savvy physicians and lack of appropriate equipment. In our experience in public hospitals in Greece, for example, before the pandemic few web-cameras were available to use by the staff, a problem that thankfully was fixed on time.

There are certainly a number of knowledge gaps with regard to the matter. On top of those implied before. A considerable gap stems from the lack of cost effectiveness data in comparison to the pre-pandemic era. which necessitates further assessment, given that a non - cost effective model of remote care has lower likelihood to survive after the pandemic. Furthermore, there is no data in regard to the physician’s perception of remote care, the level of physicians’ digital literacy, accountability and financial compensation. Again, judging from the authors’ experience, there is a lack of familiarity with concurrent technology that’s proportional to the personnel’s age, mostly affecting the most senior members of the staff. In regards to the economics of telehealth, it is unclear whether state and private insurance have a homogenous stance of compensating remote care and whether they compensate at the same rate as in-person care, which, as expected, could stress medical staff. Last but not least, it is necessary to mention that the reported studies involved limited numbers of patients monitored for a number of weeks or months.

Future research needs to address the above limitations in the form of large scale and long-term studies providing - wherever necessary - head-to-head comparisons between patients treated in physical and remote settings. Studies evaluating patients and healthcare professionals’ digital literacy can also help make digital health applications more relevant and improve the quality of the provided services. The latter calls for multidisciplinary research and initiatives involving digital health and network specialists apart from healthcare professionals, patients and caregivers.

Current evidence seems to favor the implementation of telehealth approaches to DF care. The encouraging results that have been reported thus far need to be monitored and reevaluated in the long term. Likewise, research needs to expand by getting more diverse and inclusive of a greater spectrum of socio-political landscapes. A good example of that is a recent study by Yunir et al[26] in Indonesia. We believe the conditions of the pandemic will inevitably contribute to the rapid development of the means of this method, either in the form of new software or patient and physician digital education and familiarization. This could serve as an excellent transition to the post-COVID era, as examined by Anichini et al[27], where a hybrid approach of telemedicine and in-person care will work best for all parties involved, delivering fast, efficient and cost-effective care to the patients.

Diabetic foot (DF) care requires frequent visualization, measurement and assessment of the wound by a specialist in addition to diverse treatment modalities. Therefore, limited healthcare access directly affects the care of these individuals.

There is limited evidence focusing specifically on DF care during the pandemic.

To summarize the existing research focusing on digital health and remote care for DF, its precipitating factors and sequelae and identify relevant research gaps and fields of action.

The authors searched studies published in PubMed-Medline and Cochrane Library-Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials from September 27 until October 31, 2021. The search terms: (“Digital health” OR “Remote Healthcare” OR “Telemedicine”) AND (“Diabetic Foot”[MeSH] OR “Diabetic Angiopathies”[MeSH] OR “Foot Ulcer [MeSH]” OR "Diabetic Neuropathies"[MeSH]) AND "COVID-19"[MeSH] were used.

Remote diabetic foot ulcer care appears to be comparable to standard therapy in terms of outcomes, i.e., healing time and amputation rates.

The authors believe the conditions of the pandemic will inevitably contribute to the rapid development of the means of this method, either in the form of new software or patient and physician digital education and familiarization.

These findings need to be validated with larger and long – term studies.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country/Territory of origin: Greece

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Al-Ani RM, Iraq; Moreno-Gómez-Toledano R, Spain S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Tsagkaris C, Sevdalis N, Syrigou E, Kamaratos A. Medication prescribed diabetes mellitus amid the COVID-19 pandemic in Greece: data and challenges along the way. HPHR. 2021;29. |

| 2. | Boulton AJM. Diabetic Foot Disease during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Atri A, Kocherlakota CM, Dasgupta R. Managing diabetic foot in times of COVID-19: time to put the best 'foot' forward. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. 2020;40:321-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | van Netten JJ, Bus SA, Apelqvist J, Lipsky BA, Hinchliffe RJ, Game F, Rayman G, Lazzarini PA, Forsythe RO, Peters EJG, Senneville É, Vas P, Monteiro-Soares M, Schaper NC; International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot. Definitions and criteria for diabetic foot disease. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2020;36 Suppl 1:e3268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhang Y, Lazzarini PA, McPhail SM, van Netten JJ, Armstrong DG, Pacella RE. Global Disability Burdens of Diabetes-Related Lower-Extremity Complications in 1990 and 2016. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:964-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 55.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | American Diabetes Association. The Cost of Diabetes. 2021. [cited January 7, 2022] Available from: https://www.diabetes.org/resources/statistics/cost-diabetes. |

| 7. | Armstrong DG, Swerdlow MA, Armstrong AA, Conte MS, Padula WV, Bus SA. Five year mortality and direct costs of care for people with diabetic foot complications are comparable to cancer. J Foot Ankle Res. 2020;13:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 350] [Cited by in RCA: 499] [Article Influence: 99.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Rice JB, Desai U, Cummings AK, Birnbaum HG, Skornicki M, Parsons NB. Burden of diabetic foot ulcers for medicare and private insurers. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:651-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 34.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Singh N, Armstrong DG, Lipsky BA. Preventing foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. JAMA. 2005;293:217-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1841] [Cited by in RCA: 1786] [Article Influence: 89.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhang P, Lu J, Jing Y, Tang S, Zhu D, Bi Y. Global epidemiology of diabetic foot ulceration: a systematic review and meta-analysis †. Ann Med. 2017;49:106-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 666] [Cited by in RCA: 981] [Article Influence: 122.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 11. | Prompers L, Huijberts M, Apelqvist J, Jude E, Piaggesi A, Bakker K, Edmonds M, Holstein P, Jirkovska A, Mauricio D, Ragnarson Tennvall G, Reike H, Spraul M, Uccioli L, Urbancic V, Van Acker K, van Baal J, van Merode F, Schaper N. High prevalence of ischaemia, infection and serious comorbidity in patients with diabetic foot disease in Europe. Baseline results from the Eurodiale study. Diabetologia. 2007;50:18-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 601] [Cited by in RCA: 634] [Article Influence: 35.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bandyk DF. The diabetic foot: Pathophysiology, evaluation, and treatment. Semin Vasc Surg. 2018;31:43-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 30.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rastogi A, Hiteshi P, Bhansali A A, Jude EB. Virtual triage and outcomes of diabetic foot complications during Covid-19 pandemic: A retro-prospective, observational cohort study. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0251143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Téot L, Geri C, Lano J, Cabrol M, Linet C, Mercier G. Complex Wound Healing Outcomes for Outpatients Receiving Care via Telemedicine, Home Health, or Wound Clinic: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2020;19:197-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Meloni M, Izzo V, Giurato L, Gandini R, Uccioli L. Management of diabetic persons with foot ulceration during COVID-19 health care emergency: Effectiveness of a new triage pathway. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;165:108245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shankhdhar K. Diabetic Foot Amputation Prevention During COVID-19. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2021;34:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kavitha KV, Deshpande SR, Pandit AP, Unnikrishnan AG. Application of tele-podiatry in diabetic foot management: A series of illustrative cases. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:1991-1995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ratliff CR, Shifflett R, Howell A, Kennedy C. Telehealth for Wound Management During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Case Studies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2020;47:445-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rasmussen BS, Froekjaer J, Bjerregaard MR, Lauritsen J, Hangaard J, Henriksen CW, Halekoh U, Yderstraede KB. A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Telemedical and Standard Outpatient Monitoring of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1723-1729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | van Netten JJ, Clark D, Lazzarini PA, Janda M, Reed LF. The validity and reliability of remote diabetic foot ulcer assessment using mobile phone images. Sci Rep. 2017;7:9480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Smith-Strøm H, Igland J, Østbye T, Tell GS, Hausken MF, Graue M, Skeie S, Cooper JG, Iversen MM. The Effect of Telemedicine Follow-up Care on Diabetes-Related Foot Ulcers: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Noninferiority Trial. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:96-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kilic M, Karadağ A. Developing and Evaluating a Mobile Foot Care Application for Persons With Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Pilot Study. Wound Manag Prev. 2020;66:29-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Iacopi E, Pieruzzi L, Goretti C, Piaggesi A. I fear COVID but diabetic foot (DF) is worse: a survey on patients' perception of a telemedicine service for DF during lockdown. Acta Diabetol. 2021;58:587-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fasterholdt I, Gerstrøm M, Rasmussen BSB, Yderstræde KB, Kidholm K, Pedersen KM. Cost-effectiveness of telemonitoring of diabetic foot ulcer patients. Health Informatics J. 2018;24:245-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pang B, Shah PM, Manning L, Ritter JC, Hiew J, Hamilton EJ. Management of diabetes-related foot disease in the outpatient setting during the COVID-19 pandemic. Intern Med J. 2021;51:1146-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yunir E, Tarigan TJE, Iswati E, Sarumpaet A, Christabel EV, Widiyanti D, Wisnu W, Purnamasari D, Kurniawan F, Rosana M, Anestherita F, Muradi A, Tahapary DL. Characteristics of Diabetic Foot Ulcer Patients Pre- and During COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons Learnt From a National Referral Hospital in Indonesia. J Prim Care Community Health. 2022;13:21501319221089767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Anichini R, Cosentino C, Papanas N. Diabetic Foot Syndrome in the COVID-19 era: How to Move from Classical to new Approaches. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2022;21:107-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |