Published online Dec 12, 2013. doi: 10.5528/wjtm.v2.i3.49

Revised: September 30, 2013

Accepted: November 1, 2013

Published online: December 12, 2013

Processing time: 142 Days and 22.1 Hours

Atherosclerosis is becoming an alarming disease for the existence of healthy human beings in the 21st century. There are a growing number of agents, either modernized life style generated, competitive work culture related or infection with some bacterial or viral agents, documented every year. These infectious agents do not have proper diagnostics or detection availability in many poor and developing countries. Hence, as active medical researchers, we summarize some aspects of infectious agents and their related mechanisms in this review which may be beneficial for new beginners in this field and update awareness in the field of cardiovascular biology.

Core tip: This paper describes the association of atherosclerosis with different infectious agents, specifically Chlamydia pneumoniae (C. pneumoniae), Helicobacter pylori, Herpes viruses and periodontal pathogens. There are many other bacteria and viruses, as well as life style related factors described and cited in this review. The manuscript also emphasizes how C. pneumoniae is modulating the human immune system with mimicking some antigenic proteins of the host. Overall, this report helps in the field of cardiac biology to explore associated risk factors in more detail.

- Citation: Jha HC, Mittal A. Impact of viral and bacterial infections in coronary artery disease patients. World J Transl Med 2013; 2(3): 49-55

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6132/full/v2/i3/49.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5528/wjtm.v2.i3.49

There are numerous studies supporting the association of coronary artery disease with many infectious agents, including bacteria and viruses[1-8]. Several bacterial pathogens have been reported to trigger the inflammation of atherosclerosis, including Chlamydia pneumoniae (C. pneumoniae)[7,9,10], Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)[11,12], Chryseomonas sp[13], Veillonella sp[13], Streptococcus sp[13], Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans[14], Porphyromonas gingivalis[15], Prevotella intermedia[16], Prevotella nigrescens[17], Tannerella forsythia[18], Ruminococcus enterotype[19], Enterobacter hormaechei[20] and periodontal pathogens[21]. Similarly, many viruses are known to be associated with atherosclerosis, namely cytomegalovirus (CMV)[22,23], herpesvirus[24], hepatitis A[25], B[26] and C viruses[27], Epstein-Barr virus[28] and Herpes simplex virus I and II[29]. Thus, it would be important to know in which circumstances bacterial and viral infections activate heart disease mechanistically.

Increasing the risk of heart disease is a major cause of concern. In 2008, 30% of all global death was attributed to cardiovascular diseases[30]. It is also estimated that by 2030, over 23 million people will die from cardiovascular diseases annually[30]. The incidence rate of atherosclerotic symptoms is increasing exponentially year by year[31]. There are numerous factors involved in the causation of atherosclerosis. Some researchers strongly classify it as a life style disease, including body mass weight, smoking, heavy alcohol intake, sedentary life style, blood pressure, elevated levels of cholesterol and bad lipids, reduced levels of good lipids and a stressful life[32-38]. Many studies have found a significant association of atherosclerosis with genetics or as hereditary[39], with close blood relatives suffering from heart attack, diabetes or hypertension[8,40,41]. Moreover, mainly from last decades, various studies were conducted on the association of heart disease with infectious agents. Many types of specimens, including blood samples, PBMCs and specific tissue sites were evaluated for the establishment of infection with atherosclerosis[42]. To date, there are hundreds of research studies using ELISA, standard PCR, real time quantitative PCR, cell culture, immunohistochemistry and immunocytochemistry methods to find a relevant and authentic answer for the association between infectious agents with atherosclerosis[6-8,43-49]. Although some controversy exists in this field in order to completely accept the direct association between infectious agents with atherosclerosis, there is no question of the enhanced presence of infectious agents in atherosclerosis or accelerated progression of atherosclerosis in the presence of infectious agents. To date, some well established infectious agents, like bacteria and viruses, C. pneumoniae, H. pylori and cytomegalovirus, were observed in a number of studies and explained the etiology of disease causation in detail[50-53].

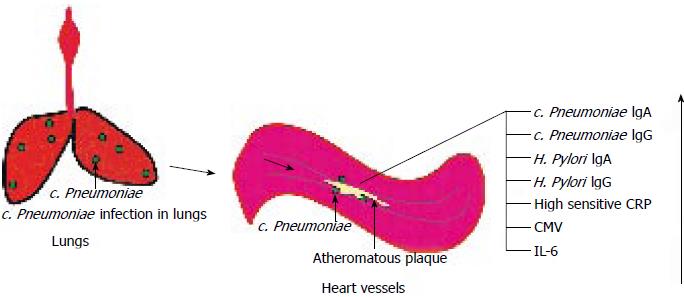

C. pneumoniae is an intracellular obligatory bacteria which causes upper and lower respiratory tract infections[54]. Other than respiratory disease, C. pneumoniae has been found to be associated with heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, lung cancer and arthritis[55-59]. 95% of the population is exposed to C. pneumoniae in their life time; however, this exposure is asymptomatic while in contact with C. pneumoniae frequently and exposure to some other co-activator of C. pneumoniae infection triggers the establishment of infection and chronicity of disease pathogenesis[60]. There are numerous tissue or body organelles involved in the acceleration of C. pneumoniae infection[61,62]. Correct diagnosis of infectious agents is always in question and many methodological improvements have been made in this aspect[63,64]. To date, nested PCR or quantitative probe based real time PCR methods have been largely updated in this field[7,65,66]. 16S rRNA and major outer membrane protein have been found to be critical for identification on PCR based methods[7,67,68]. Moreover, immunoglobulin based screening also has significance and capability for the predication of disease occurrence in existing non-symptomatic and close relative populations of patients[41]. In many studies, C. pneumoniae specific immunoglobulin IgA has been found to be more predictive and robustly observed compared to IgG in the serum of coronary artery disease patients[8,69,70], while some studies reported it vice versa as well[71]. In response to C. pneumoniae infection, many host immune responses are manipulated or aggravated to counter the effect of bacterial pathogens and stop the progression of disease, while at the same time, this smart bacteria also activates host signaling by mimicking some of the key proteins, starting to accelerate disease progression[49,72,73]. These host-pathogen responses are very complex and many studies find some narrative result which suggests the hypothetical model for the infection progression due to C. pneumoniae[74]. Moreover, details are needed to explore this field to prevent infection of the human population from these kinds of opportunistic pathogens.

H. pylori is known to be an active initiator of gastric carcinoma[75]. Moreover, the presence of H. pylori has been found to be associated significantly in atheromatous plaque[76]. In our study, we found significant H. pylori IgA antibody titer in CAD patients compared to controls and levels of H. pylori IgG were also high[8]. Furthermore, we also detected H. pylori DNA in atheromatous plaque by using quantitative real time PCR[6]. There are many other reports also suggesting the active involvement of H. pylori in the development of atherosclerosis[11,77,78]. However, it is important to know in which circumstances this bacterium activates oncogenesis and heart disease.

CMV is an important pathogenic virus which causes many chronic diseases, such as cancer and atherosclerosis[79-82]. There is growing evidence supporting the synergistic effect of infectious agents in the progression of heart disease[50,83]. In our antibody titer detection assay and PCR assay, we found higher positivity for CMV in CAD patients compared to controls[6]. However, there is lots of space where we can identify the initiator organism or activator organism among many infections which may alter the immune response of systems.

Evidence suggests that human herpes viruses have a potential link to arterial injury[83]. This hypothesis is proven in animal model studies, as well as a clinical epidemiological association between herpes viral infection and accelerated arteriosclerosis[84]. Studies suggested that eight members of the herpes virus family member may infect humans[85]. Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1), herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and CMV are widespread in the general population; they are primary candidates for investigations into viruses related to atherosclerosis[86].

A definite association was found for HSV-2 and subclinical coronary atherosclerosis[87]. This organism has been shown to be responsible for thrombogenic and atherogenic changes to host cells[88]. Earlier association of HSV-2 with hypertension has been reported[89]. These days, many studies emphasize the role of inflammatory pathways in atherosclerosis development[90]. Furthermore, recently Horváth et al[91] suggested that long-term HSV-2 infection may contribute to the development of atherosclerosis.

Many earlier studies demonstrated that only atherosclerotic tissues majorly have multiple infections[86]. Researchers also suggested that the synergistic impact of infection on atherogenesis is related to the aggregate number of pathogens infecting human beings[92]. Several serological studies demonstrated that all these pathogens (CMV, EBV, hepatitis A virus, HSV-1, HSV-2 and C. pneumoniae) are variably associated with the risk of CAD[4]. Shi et al[86] detected HSV-1, EBV and CMV DNA in the upper part of the non-atherosclerotic aortic wall and these viral DNA were also detected more extensively in atherosclerotic lesions compared to non-atherosclerotic tissue.

There are several reports with an emphasis on the association of dental disease with elevated risk of myocardial infarction[93] and metabolic activity of the gut microbiota has also been shown to be related to blood pressure[94]. Several other studies also suggested an oral source for atherosclerotic plaque-associated bacteria[95,96]. Chryseomonas sp was present in endocarditis and all atherosclerotic plaque samples[97].

Many species, namely Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, are actively involved in periodontal disease and have been reported as a potential risk for the development of atherosclerosis[98]. Animal studies have also proven this association[99].

Beside these infectious agents, other factors that may incite vessel inflammation are oxidized low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and the metabolic syndrome, which are associated with a proinflammatory condition characterized by elevations of C-reactive protein or high sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP)[100-102]. Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of abnormalities caused by elevation of multiple metabolic pathways, hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance in body organelles, hyperglycemia, atherogenic dyslipidemia, abdominal obesity and hypertension[103-104]. In our study, we found the association of hs-CRP with elevated levels of C. pneumoniae IgA and H. pylori IgA[8]. We also observed higher proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-6 positively associated with hs-CRP[100]. Furthermore, our study extended the knowledge in respect of the association between C. pneumoniae IgA with Th-1, Th-2, Th-3 or adhesion molecules[101], although these markers were labeled as independent markers for CAD in our study[105]. There are many studies that suggest that Th-1 cytokines or proinflammatory cytokines are expressed earlier after C. pneumoniae infection followed by Th-2 kind of cytokines[106-107]; however mechanistically it moves in the case of humans is still evaded. We draw a schematic for C. pneumoniae in atherosclerosis (Figure 1).

P- Reviewers: Han Q, Niculescu M S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Muhlestein JB, Anderson JL. Chronic infection and coronary artery disease. Cardiol Clin. 2003;21:333-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Roivainen M, Viik-Kajander M, Palosuo T, Toivanen P, Leinonen M, Saikku P, Tenkanen L, Manninen V, Hovi T, Mänttäri M. Infections, inflammation, and the risk of coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2000;101:252-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rosenfeld ME, Campbell LA. Pathogens and atherosclerosis: update on the potential contribution of multiple infectious organisms to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106:858-867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rupprecht HJ, Blankenberg S, Bickel C, Rippin G, Hafner G, Prellwitz W, Schlumberger W, Meyer J. Impact of viral and bacterial infectious burden on long-term prognosis in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2001;104:25-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Watt S, Aesch B, Lanotte P, Tranquart F, Quentin R. Viral and bacterial DNA in carotid atherosclerotic lesions. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;22:99-105. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Jha HC, Srivastava P, Divya A, Prasad J, Mittal A. Prevalence of Chlamydophila pneumoniae is higher in aorta and coronary artery than in carotid artery of coronary artery disease patients. APMIS. 2009;117:905-911. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Jha HC, Vardhan H, Gupta R, Varma R, Prasad J, Mittal A. Higher incidence of persistent chronic infection of Chlamydia pneumoniae among coronary artery disease patients in India is a cause of concern. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jha HC, Prasad J, Mittal A. High immunoglobulin A seropositivity for combined Chlamydia pneumoniae, Helicobacter pylori infection, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in coronary artery disease patients in India can serve as atherosclerotic marker. Heart Vessels. 2008;23:390-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sessa R, Nicoletti M, Di Pietro M, Schiavoni G, Santino I, Zagaglia C, Del Piano M, Cipriani P. Chlamydia pneumoniae and atherosclerosis: current state and future prospectives. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2009;22:9-14. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Shor A, Phillips JI. Chlamydia pneumoniae and atherosclerosis. JAMA. 1999;282:2071-2073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ameriso SF, Fridman EA, Leiguarda RC, Sevlever GE. Detection of Helicobacter pylori in human carotid atherosclerotic plaques. Stroke. 2001;32:385-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mayr M, Kiechl S, Mendall MA, Willeit J, Wick G, Xu Q. Increased risk of atherosclerosis is confined to CagA-positive Helicobacter pylori strains: prospective results from the Bruneck study. Stroke. 2003;34:610-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Koren O, Spor A, Felin J, Fåk F, Stombaugh J, Tremaroli V, Behre CJ, Knight R, Fagerberg B, Ley RE. Human oral, gut, and plaque microbiota in patients with atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108 Suppl 1:4592-4598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 687] [Cited by in RCA: 857] [Article Influence: 57.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhang T, Kurita-Ochiai T, Hashizume T, Du Y, Oguchi S, Yamamoto M. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans accelerates atherosclerosis with an increase in atherogenic factors in spontaneously hyperlipidemic mice. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2010;59:143-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hayashi C, Viereck J, Hua N, Phinikaridou A, Madrigal AG, Gibson FC, Hamilton JA, Genco CA. Porphyromonas gingivalis accelerates inflammatory atherosclerosis in the innominate artery of ApoE deficient mice. Atherosclerosis. 2011;215:52-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gaetti-Jardim E, Marcelino SL, Feitosa AC, Romito GA, Avila-Campos MJ. Quantitative detection of periodontopathic bacteria in atherosclerotic plaques from coronary arteries. J Med Microbiol. 2009;58:1568-1575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yakob M, Söder B, Meurman JH, Jogestrand T, Nowak J, Söder PÖ. Prevotella nigrescens and Porphyromonas gingivalis are associated with signs of carotid atherosclerosis in subjects with and without periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 2011;46:749-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rivera MF, Lee JY, Aneja M, Goswami V, Liu L, Velsko IM, Chukkapalli SS, Bhattacharyya I, Chen H, Lucas AR. Polymicrobial infection with major periodontal pathogens induced periodontal disease and aortic atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic ApoE (null) mice. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Karlsson FH, Fåk F, Nookaew I, Tremaroli V, Fagerberg B, Petranovic D, Bäckhed F, Nielsen J. Symptomatic atherosclerosis is associated with an altered gut metagenome. Nat Commun. 2012;3:1245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 711] [Cited by in RCA: 933] [Article Influence: 77.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rafferty B, Dolgilevich S, Kalachikov S, Morozova I, Ju J, Whittier S, Nowygrod R, Kozarov E. Cultivation of Enterobacter hormaechei from human atherosclerotic tissue. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2011;18:72-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fiehn NE, Larsen T, Christiansen N, Holmstrup P, Schroeder TV. Identification of periodontal pathogens in atherosclerotic vessels. J Periodontol. 2005;76:731-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xenaki E, Hassoulas J, Apostolakis S, Sourvinos G, Spandidos DA. Detection of cytomegalovirus in atherosclerotic plaques and nonatherosclerotic arteries. Angiology. 2009;60:504-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zhu J, Quyyumi AA, Norman JE, Csako G, Epstein SE. Cytomegalovirus in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: the role of inflammation as reflected by elevated C-reactive protein levels. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1738-1743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Alber DG, Powell KL, Vallance P, Goodwin DA, Grahame-Clarke C. Herpesvirus infection accelerates atherosclerosis in the apolipoprotein E-deficient mouse. Circulation. 2000;102:779-785. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Zhu J, Quyyumi AA, Norman JE, Costello R, Csako G, Epstein SE. The possible role of hepatitis A virus in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1583-1587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ishizaka N, Ishizaka Y, Takahashi E, Toda Ei E, Hashimoto H, Ohno M, Nagai R, Yamakado M. Increased prevalence of carotid atherosclerosis in hepatitis B virus carriers. Circulation. 2002;105:1028-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Butt AA, Xiaoqiang W, Budoff M, Leaf D, Kuller LH, Justice AC. Hepatitis C virus infection and the risk of coronary disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:225-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Binkley PF, Cooke GE, Lesinski A, Taylor M, Chen M, Laskowski B, Waldman WJ, Ariza ME, Williams MV, Knight DA. Evidence for the role of Epstein Barr Virus infections in the pathogenesis of acute coronary events. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kotronias D, Kapranos N. Herpes simplex virus as a determinant risk factor for coronary artery atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction. In Vivo. 2005;19:351-357. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Robinson JG, Fox KM, Bullano MF, Grandy S. Atherosclerosis profile and incidence of cardiovascular events: a population-based survey. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2009;9:46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ambrose JA, Barua RS. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: an update. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1731-1737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1527] [Cited by in RCA: 1631] [Article Influence: 77.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Burnett JR. Lipids, lipoproteins, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. Clin Biochem Rev. 2004;25:2. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Huszar D, Varban ML, Rinninger F, Feeley R, Arai T, Fairchild-Huntress V, Donovan MJ, Tall AR. Increased LDL cholesterol and atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice with attenuated expression of scavenger receptor B1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1068-1073. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kiechl S, Willeit J, Rungger G, Egger G, Oberhollenzer F, Bonora E. Alcohol consumption and atherosclerosis: what is the relation? Prospective results from the Bruneck Study. Stroke. 1998;29:900-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Mainous AG, Everett CJ, Diaz VA, Player MS, Gebregziabher M, Smith DW. Life stress and atherosclerosis: a pathway through unhealthy lifestyle. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2010;40:147-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Rossi R, Iaccarino D, Nuzzo A, Chiurlia E, Bacco L, Venturelli A, Modena MG. Influence of body mass index on extent of coronary atherosclerosis and cardiac events in a cohort of patients at risk of coronary artery disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;21:86-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | van Leeuwen R, Ikram MK, Vingerling JR, Witteman JC, Hofman A, de Jong PT. Blood pressure, atherosclerosis, and the incidence of age-related maculopathy: the Rotterdam Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3771-3777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kovacic S, Bakran M. Genetic susceptibility to atherosclerosis. Stroke Res Treat. 2012;2012:362941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | O'Donnell CJ. Family history, subclinical atherosclerosis, and coronary heart disease risk: barriers and opportunities for the use of family history information in risk prediction and prevention. Circulation. 2004;110:2074-2076. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Jha HC, Mittal A. Coronary artery disease patient’s first degree relatives may be at higher risk for atherosclerosis. Int J Cardiol. 2009;135:408-409; author reply 410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Gómez-Hernández A, Martín-Ventura JL, Sánchez-Galán E, Vidal C, Ortego M, Blanco-Colio LM, Ortega L, Tuñón J, Egido J. Overexpression of COX-2, Prostaglandin E synthase-1 and prostaglandin E receptors in blood mononuclear cells and plaque of patients with carotid atherosclerosis: regulation by nuclear factor-kappaB. Atherosclerosis. 2006;187:139-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Estrada R, Giridharan G, Prabhu SD, Sethu P. Endothelial cell culture model of carotid artery atherosclerosis. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2011;2011:186-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kosierkiewicz TA, Factor SM, Dickson DW. Immunocytochemical studies of atherosclerotic lesions of cerebral berry aneurysms. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1994;53:399-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Mallat Z, Corbaz A, Scoazec A, Besnard S, Lesèche G, Chvatchko Y, Tedgui A. Expression of interleukin-18 in human atherosclerotic plaques and relation to plaque instability. Circulation. 2001;104:1598-1603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 402] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Pedretti M, Rancic Z, Soltermann A, Herzog BA, Schliemann C, Lachat M, Neri D, Kaufmann PA. Comparative immunohistochemical staining of atherosclerotic plaques using F16, F8 and L19: Three clinical-grade fully human antibodies. Atherosclerosis. 2010;208:382-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Smith BW, Strakova J, King JL, Erdman JW, O’Brien WD. Validated sandwich ELISA for the quantification of von Willebrand factor in rabbit plasma. Biomark Insights. 2010;5:119-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | van Eck M, Bos IS, Kaminski WE, Orsó E, Rothe G, Twisk J, Böttcher A, Van Amersfoort ES, Christiansen-Weber TA, Fung-Leung WP. Leukocyte ABCA1 controls susceptibility to atherosclerosis and macrophage recruitment into tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:6298-6303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Jha HC, Srivastava P, Vardhan H, Singh LC, Bhengraj AR, Prasad J, Mittal A. Chlamydia pneumoniae heat shock protein 60 is associated with apoptotic signaling pathway in human atheromatous plaques of coronary artery disease patients. J Cardiol. 2011;58:216-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Latsios G, Saetta A, Michalopoulos NV, Agapitos E, Patsouris E. Detection of cytomegalovirus, Helicobacter pylori and Chlamydia pneumoniae DNA in carotid atherosclerotic plaques by the polymerase chain reaction. Acta Cardiol. 2004;59:652-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Bloemenkamp DG, Mali WP, Tanis BC, Rosendaal FR, van den Bosch MA, Kemmeren JM, Algra A, Ossewaarde JM, Visseren FL, van Loon AM. Chlamydia pneumoniae, Helicobacter pylori and cytomegalovirus infections and the risk of peripheral arterial disease in young women. Atherosclerosis. 2002;163:149-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Witherell HL, Smith KL, Friedman GD, Ley C, Thom DH, Orentreich N, Vogelman JH, Parsonnet J. C-reactive protein, Helicobacter pylori, Chlamydia pneumoniae, cytomegalovirus and risk for myocardial infarction. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:170-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Virok D, Kis Z, Kari L, Barzo P, Sipka R, Burian K, Nelson DE, Jackel M, Kerenyi T, Bodosi M. Chlamydophila pneumoniae and human cytomegalovirus in atherosclerotic carotid plaques--combined presence and possible interactions. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2006;53:35-50. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Grayston JT. Infections caused by Chlamydia pneumoniae strain TWAR. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:757-761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Belland RJ, Ouellette SP, Gieffers J, Byrne GI. Chlamydia pneumoniae and atherosclerosis. Cell Microbiol. 2004;6:117-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Campbell LA, Kuo CC, Grayston JT. Chlamydia pneumoniae and cardiovascular disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:571-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Chaturvedi AK, Gaydos CA, Agreda P, Holden JP, Chatterjee N, Goedert JJ, Caporaso NE, Engels EA. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and risk for lung cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1498-1505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Fainardi E, Castellazzi M, Seraceni S, Granieri E, Contini C. Under the microscope: focus on Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and multiple sclerosis. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2008;5:60-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Hammond CJ, Hallock LR, Howanski RJ, Appelt DM, Little CS, Balin BJ. Immunohistological detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae in the Alzheimer’s disease brain. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11:121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Karunakaran KP, Blanchard JF, Raudonikiene A, Shen C, Murdin AD, Brunham RC. Molecular detection and seroepidemiology of the Chlamydia pneumoniae bacteriophage (PhiCpn1). J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:4010-4014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Gieffers J, Füllgraf H, Jahn J, Klinger M, Dalhoff K, Katus HA, Solbach W, Maass M. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in circulating human monocytes is refractory to antibiotic treatment. Circulation. 2001;103:351-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Mosorin M, Surcel HM, Laurila A, Lehtinen M, Karttunen R, Juvonen J, Paavonen J, Morrison RP, Saikku P, Juvonen T. Detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae-reactive T lymphocytes in human atherosclerotic plaques of carotid artery. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1061-1067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Boman J, Hammerschlag MR. Chlamydia pneumoniae and atherosclerosis: critical assessment of diagnostic methods and relevance to treatment studies. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:1-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Ieven MM, Hoymans VY. Involvement of Chlamydia pneumoniae in atherosclerosis: more evidence for lack of evidence. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:19-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Hardick J, Maldeis N, Theodore M, Wood BJ, Yang S, Lin S, Quinn T, Gaydos C. Real-time PCR for Chlamydia pneumoniae utilizing the Roche Lightcycler and a 16S rRNA gene target. J Mol Diagn. 2004;6:132-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Tondella ML, Talkington DF, Holloway BP, Dowell SF, Cowley K, Soriano-Gabarro M, Elkind MS, Fields BS. Development and evaluation of real-time PCR-based fluorescence assays for detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:575-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Meijer A, Roholl PJ, Gielis-Proper SK, Ossewaarde JM. Chlamydia pneumoniae antigens, rather than viable bacteria, persist in atherosclerotic lesions. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:911-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Meijer A, van Der Vliet JA, Roholl PJ, Gielis-Proper SK, de Vries A, Ossewaarde JM. Chlamydia pneumoniae in abdominal aortic aneurysms: abundance of membrane components in the absence of heat shock protein 60 and DNA. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2680-2686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Apfalter P. Chlamydia pneumoniae, stroke, and serological associations: anything learned from the atherosclerosis-cardiovascular literature or do we have to start over again? Stroke. 2006;37:756-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Wolf SC, Mayer O, Jürgens S, Vonthein R, Schultze G, Risler T, Brehm BR. Chlamydia pneumoniae IgA seropositivity is associated with increased risk for atherosclerotic vascular disease, myocardial infarction and stroke in dialysis patients. Clin Nephrol. 2003;59:273-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Podsiadły E, Przyłuski J, Kwiatkowski A, Kruk M, Wszoła M, Nosek R, Rowiński W, Ruzyłło W, Tylewska-Wierzbanowska S. Presence of Chlamydia pneumoniae in patients with and without atherosclerosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;24:507-513. [PubMed] |

| 71. | Huittinen T, Hahn D, Anttila T, Wahlström E, Saikku P, Leinonen M. Host immune response to Chlamydia pneumoniae heat shock protein 60 is associated with asthma. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:1078-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Jha HC, Srivastava P, Prasad J, Mittal A. Chlamydia pneumoniae heat shock protein 60 enhances expression of ERK, TLR-4 and IL-8 in atheromatous plaques of coronary artery disease patients. Immunol Invest. 2011;40:206-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Di Pietro M, Filardo S, De Santis F, Sessa R. Chlamydia pneumoniae infection in atherosclerotic lesion development through oxidative stress: a brief overview. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:15105-15120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Sugiyama T, Hige S, Asaka M. Development of an H. pylori-infected animal model and gastric cancer: recent progress and issues. J Gastroenterol. 2002;37 Suppl 13:6-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Kowalski M. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection in coronary artery disease: influence of H. pylori eradication on coronary artery lumen after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. The detection of H. pylori specific DNA in human coronary atherosclerotic plaque. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2001;52:3-31. [PubMed] |

| 76. | Ayada K, Yokota K, Hirai K, Fujimoto K, Kobayashi K, Ogawa H, Hatanaka K, Hirohata S, Yoshino T, Shoenfeld Y. Regulation of cellular immunity prevents Helicobacter pylori-induced atherosclerosis. Lupus. 2009;18:1154-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Khalil MZ. The association of Helicobacter pylori infection with coronary artery disease: fact or fiction? Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:132-139. [PubMed] |

| 78. | Bentz GL, Yurochko AD. Human CMV infection of endothelial cells induces an angiogenic response through viral binding to EGF receptor and beta1 and beta3 integrins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5531-5536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Mariguela VC, Chacha SG, Cunha Ade A, Troncon LE, Zucoloto S, Figueiredo LT. Cytomegalovirus in colorectal cancer and idiopathic ulcerative colitis. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2008;50:83-87. [PubMed] |

| 80. | Sambiase NV, Higuchi ML, Nuovo G, Gutierrez PS, Fiorelli AI, Uip DE, Ramires JA. CMV and transplant-related coronary atherosclerosis: an immunohistochemical, in situ hybridization, and polymerase chain reaction in situ study. Mod Pathol. 2000;13:173-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Utrera-Barillas D, Valdez-Salazar HA, Gómez-Rangel D, Alvarado-Cabrero I, Aguilera P, Gómez-Delgado A, Ruiz-Tachiquin ME. Is human cytomegalovirus associated with breast cancer progression? Infect Agent Cancer. 2013;8:12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Al-Ghamdi A, Jiman-Fatani AA, El-Banna H. Role of Chlamydia pneumoniae, helicobacter pylori and cytomegalovirus in coronary artery disease. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2011;24:95-101. [PubMed] |

| 83. | Morré SA, Stooker W, Lagrand WK, van den Brule AJ, Niessen HW. Microorganisms in the aetiology of atherosclerosis. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:647-654. [PubMed] |

| 84. | Minick CR, Fabricant CG, Fabricant J, Litrenta MM. Atheroarteriosclerosis induced by infection with a herpesvirus. Am J Pathol. 1979;96:673-706. [PubMed] |

| 85. | Frenkel N, Schirmer EC, Wyatt LS, Katsafanas G, Roffman E, Danovich RM, June CH. Isolation of a new herpesvirus from human CD4+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:748-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Shi Y, Tokunaga O. Herpesvirus (HSV-1, EBV and CMV) infections in atherosclerotic compared with non-atherosclerotic aortic tissue. Pathol Int. 2002;52:31-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 87. | Benditt EP, Barrett T, McDougall JK. Viruses in the etiology of atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:6386-6389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Epstein SE, Zhou YF, Zhu J. Infection and atherosclerosis: emerging mechanistic paradigms. Circulation. 1999;100:e20-e28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Sun Y, Pei W, Wu Y, Jing Z, Zhang J, Wang G. Herpes simplex virus type 2 infection is a risk factor for hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2004;27:541-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1135-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4640] [Cited by in RCA: 4851] [Article Influence: 210.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Horváth R, Cerný J, Benedík J, Hökl J, Jelínková I, Benedík J. The possible role of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) in the origin of atherosclerosis. J Clin Virol. 2000;16:17-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Zhu J, Quyyumi AA, Norman JE, Csako G, Waclawiw MA, Shearer GM, Epstein SE. Effects of total pathogen burden on coronary artery disease risk and C-reactive protein levels. Am J Cardiol. 2000;85:140-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Mattila KJ, Nieminen MS, Valtonen VV, Rasi VP, Kesäniemi YA, Syrjälä SL, Jungell PS, Isoluoma M, Hietaniemi K, Jokinen MJ. Association between dental health and acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1989;298:779-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 661] [Cited by in RCA: 649] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Holmes E, Loo RL, Stamler J, Bictash M, Yap IK, Chan Q, Ebbels T, De Iorio M, Brown IJ, Veselkov KA. Human metabolic phenotype diversity and its association with diet and blood pressure. Nature. 2008;453:396-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 897] [Cited by in RCA: 794] [Article Influence: 46.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Haraszthy VI, Zambon JJ, Trevisan M, Zeid M, Genco RJ. Identification of periodontal pathogens in atheromatous plaques. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1554-1560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 710] [Cited by in RCA: 717] [Article Influence: 28.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Stelzel M, Conrads G, Pankuweit S, Maisch B, Vogt S, Moosdorf R, Flores-de-Jacoby L. Detection of Porphyromonas gingivalis DNA in aortic tissue by PCR. J Periodontol. 2002;73:868-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Casalta JP, Fournier PE, Habib G, Riberi A, Raoult D. Prosthetic valve endocarditis caused by Pseudomonas luteola. BMC Infect Dis. 2005;5:82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Ford PJ, Gemmell E, Chan A, Carter CL, Walker PJ, Bird PS, West MJ, Cullinan MP, Seymour GJ. Inflammation, heat shock proteins and periodontal pathogens in atherosclerosis: an immunohistologic study. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2006;21:206-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Lockhart PB, Bolger AF, Papapanou PN, Osinbowale O, Trevisan M, Levison ME, Taubert KA, Newburger JW, Gornik HL, Gewitz MH. Periodontal disease and atherosclerotic vascular disease: does the evidence support an independent association?: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:2520-2544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 660] [Cited by in RCA: 716] [Article Influence: 55.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Jha HC, Srivastava P, Sarkar R, Prasad J, Mittal A. Chlamydia pneumoniae IgA and elevated level of IL-6 may synergize to accelerate coronary artery disease. J Cardiol. 2008;52:140-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Jha HC, Srivastava P, Sarkar R, Prasad J, Mittal AS. Association of plasma circulatory markers, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and high sensitive C-reactive protein in coronary artery disease patients of India. Mediators Inflamm. 2009;2009:561532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Johnston SC, Messina LM, Browner WS, Lawton MT, Morris C, Dean D. C-reactive protein levels and viable Chlamydia pneumoniae in carotid artery atherosclerosis. Stroke. 2001;32:2748-2752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Paneni F, Beckman JA, Creager MA, Cosentino F. Diabetes and vascular disease: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and medical therapy: part I. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2436-2443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Semenkovich CF. Insulin resistance and atherosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1813-1822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Jha HC, Divya A, Prasad J, Mittal A. Plasma circulatory markers in male and female patients with coronary artery disease. Heart Lung. 2010;39:296-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Ait-Oufella H, Taleb S, Mallat Z, Tedgui A. Recent advances on the role of cytokines in atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:969-979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 443] [Cited by in RCA: 417] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Cytokines in atherosclerosis: pathogenic and regulatory pathways. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:515-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1139] [Cited by in RCA: 1242] [Article Influence: 65.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |