Revised: November 20, 2013

Accepted: January 13, 2014

Published online: February 6, 2014

Processing time: 286 Days and 5.1 Hours

This study is an excerpt of broad-based office practice which is designed to treat patients with diabetes and hypertension, the two most common causes of chronic kidney disease (CKD), as well as CKD of unknown etiology. This model of office practice is dedicated to evaluating patients with CKD for their complete well-being; blood pressure control, fluid control and maintenance of acid-base status and hemoglobin. Frequent office visits, every four to six weeks, confer a healthy life style year after year associated with a feeling of good well-being and a positive outlook. Having gained that, such patients remain compliant to their medication and diet, and scheduled laboratory and office visits which are determinant of a dialysis-free life.

Core tip: Diabetes and hypertension are two most common causes of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Nephrology office practice constitutes vast majority of the patients with CKD of different stages. While CKD stages 1-3 [glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (< 60 - > 30 mL/min)] produce slight or no symptoms or signs, CKD stages 4-6 (GFR < 30 - < 10 mL/min) may increase blood pressure and produce fluid electrolyte and acid-based disorders. The goal of office practice is to identify these disorders, then treat them to enable patients to live asymptomatically.

- Citation: Mandal AK. Frequent office visits of patients with chronic kidney disease: Is a prelude to prevention of dialysis. World J Nephrol 2014; 3(1): 1-5

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v3/i1/1.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v3.i1.1

Experience in direct patient care reveals that frequent office visits of patients encompassing chronic illnesses such as hypertension, diabetes, or chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a form of salutary care. This model of direct patient care is advantageous for the patients; it is educational and economical. This model of patient care is advantageous because of continuity of care which permits the patients to gain confidence in their physicians and allows them to feel comfortable in addressing their issues freely.

Similarly, continuity of care permits the physicians to identify and resolve the issues in a comfortable fashion. Other authors have reported that continuity of care has led to improved outcomes of diabetes care, delivery of preventative care and clinical satisfaction, while also decreasing the number of emergency room visits, hospitalizations, readmissions and reducing length of stay[1].

There is an interesting study which asked the question: If an outpatient repeatedly sees the same practitioner, is his care influenced? A double blind randomized trial examined the effects of outpatient health care provider continuity on the process and outcome of the medical care for 776 men aged 55 years and older. Participants were randomized to two groups of provider care: provider discontinuity and provider continuity. During an 18 mo period, continuity group had fewer emergency admissions (20% vs 39%) and a shorter average length of hospital stay (15.5 d vs 25.5 d). The continuity group also felt that the providers were more knowledgeable, thorough and interested in patient education[2].

Giving autonomy or independence in self-care motivates patients to control their illness with prescribed medication, diet, and physical therapy uniquely in illnesses such as diabetes, hypertension or CKD. In one study, 128 patients with diabetes were tested and found to achieve significant reductions in their HbA1c values over 12 mo[3]. It is important to know that understanding of side effects of medication corresponded to compliance with any proposed regimen (87% cases vs 93% control: non-significant).

Despite the similarity between the two groups, 53% of cases reported that side effects of medication were explained to them, in contrast to 84% of controls. This difference is significant indicating that the side effects of therapy are often not explained to the patients[4].

Other studies have noted that a relationship exists between the way in which physicians and patients behave during an office visit and that relationship influences patients’ subsequent health status. More control by the patients, less control by physicians, more negative effect expressed by both, more effective information seeking by patients, and greater overall patient conversation relative to the physician were consistently related to better control of diabetes and hypertension as measured by hemoglobin A1c and diastolic blood pressure (BP) respectively[5].

Having given that background, it is time to illustrate how chronic diseases like diabetes, hypertension or chronic kidney disease (CKD) of unknown etiology can be followed in the office setting for an indefinite period to ensure a good living for the patient. The goal of frequent office visits is to afford asymptomatic state, reduce hospitalization and prolong comfortable survival without dialysis therapy. Two patients are exemplified to that effect.

April 2008 - first visit: A-84-year-white female referred for end stage renal disease, without history of diabetes. Patient was not aware that she was treated for hypertension and exhibited no symptoms. Physical examination revealed pulse 64/min irregular, sitting BP 140/100 mmHg, standing BP 140/90 mmHg, and chest auscultation revealed rhonchi and a questionable mass with tenderness in the left iliac fossa. Her medication included ergo/chole calciferol 2.5 mcg per oral daily, levothyroxine 75 mcg per oral daily, amlodipine 5 mg per oral daily, sodium bicarbonate 650 mg per oral three times daily, and irbesartan 75 mg per oral daily.

She brought a laboratory which was done the previous October. The findings were glucose 96 mg/dL, BUN 49 mg/dL, serum creatinine 4.3 mg/dL, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 10 mL/min, Na+ 143 mmol/L, K+ 4.3 mmol/L, chloride 106 mmol/L, CO2 25.6 mmol/L, phosphorous 4.3 mg/dL, albumin 3.9 g/dL, calcium 9.9 mg/dL hemoglobin 11.8 g/dL and hematocrit 34.9%. A urinalysis revealed protein 1+, bacteria 4+, and WBC 33/HPF. A CT scan of the abdomen done in 2001 revealed bilaterally small kidneys. Assessment was end stage renal disease. She was admitted to a local hospital for further assessment. Irbesartan was discontinued. She was treated with bicarbonate infusion and released. No dialysis was recommended. Through the years, patient has done well, remained asymptomatic but required once a year hospital admission for diarrhea and dehydration or poor appetite. Her appetite is markedly increased with initiation of megestrol. BP control was achieved with increased dose of amlodipine. Serum bicarbonate level is maintained near normal level with increased dosage of sodium bicarbonate.

Most recent visit in March of 2013, 5 years later: Symptoms: none; Appetite: good; Activity: normal; Essential medications: (1) amlodipine 10 mg per oral daily; (2) sodium bicarbonate 1300 mg per oral 4 times daily; (3) potassium chloride 20 meq per oral daily for hypokalemia. (4) appetite stimulant megestrol, 40 mg per oral daily; (5) hectoral (ergo/chole calciferol) 2.5 mcg per oral daily; (6) levothyroxine 125 mcg per oral daily; and (7) allopurinol 150 mg per oral daily. physical examination: no edema, BP 120/80 mmhg, electrocardiogram normal; Laboratory: glucose 145 mg/dL, BUN 61 mg/dL, serum creatinine 7.8 mg/dL, eGFR 5 mL/min, Na+ 144 mmol/L, K+ 4.3 mmol/L, chloride 109 mmol/L, CO2 21 mmol/L, phosphorous 3.5 mg/dL, albumin 3.7 g/dL, intact parathyroid hormone 97 pg/mL; Plans: (1) continue current therapy; (2) No dialysis is recommended; and (3) Office visits are scheduled every 6 wk.

March 2008 - first visit: Chief complaint: breathing trouble for 2-3 years. Patient gave history of hypertension for 5 years. Significant past history includes coronary angioplasty with rupture of the coronary artery followed by coronary artery bypass graft in 1992; back surgery × 4, last one in 1995. Smoked until 1990 then quit. Significant finding on physical exam was elevated BP sitting 180/110 and 170/106 mmHg standing and pulse rate 98 per minute. A questionable bruit heard left to umbilicus. Funduscopic exam reveals arterial narrowing. Disc could not be visualized. He obtained a laboratory in March 2006 which showed hemoglobin 13.5 g/dL, hematocrit 39.5%, BUN 21 mg/dL, serum creatinine 1.9 mg/dL, eGFR 37.6 mL/min, CO2 27 mmol/L, and albumin 3.7 g/dL. Medication at this first office visit included amlodipine 5 mg per oral daily, furosemide 40 mg per oral daily, simvastatin 10 mg per oral daily, prednisone 10 mg per oral daily and albuterol inhalation. Laboratory done in February 2008 showed BUN 28 mg/dL, serum creatinine 2.6 mg/dL, glucose 105 mg/dL, Na 145 mmol/L, K 4.1 mmol/L, eGFR 26 mL/min. One month later in March 2008, his hemoglobin was 13.1 g/dL, hematocrit 39.3%, renin 0.6 ng/mL per hour, aldosterone 3 ng/dL. Medication was adjusted to include tenormin 50 mg per oral daily, increase amlodipine 5 mg twice daily and reduce furosemide 40 mg per oral every other day and prednisone 5 mg per oral daily. Two weeks later his BP decreased to 140/90 mmHg sitting and 130/90 mmHg standing and pulse rate was reduced to 66 beats/min. Soon thereafter his BP became normal. He records his BP at home and they are all normal of average less than 130/80 mmHg. He is followed in the office every six to seven weeks with laboratory done before each visit.

Most recent visit in February of 2013, 5 years later: Symptoms: none; Shortness of breath on exertion: none; Sitting BP: 120/70 mmHg; Current medications: atenolol 50 mg per oral daily, bumetanide 1 mg per oral Mondays and Fridays, amlodipine 10 mg per oral twice daily, digoxin 0.125 mg per oral Mondays, Wednesdays, Fridays and Sundays, sodium bicarbonate 1300 mg three times daily and sodium polysterene sulfonate (Kayexalate) in 30% sorbitol 5 g in 20 mL twice daily. Laboratory (Fasting) glucose 107 mg/dL, BUN 35 mg/dL, serum creatinine 2.48 mg/dL, eGFR 24 mL/min, sodium 142 mmol/L, potassium 4.5 mmol/L, calcium 9.8 mg/dL, phosphorous 4.3 mg/dL, intact PTH 178 pg/mL, uric acid 8 mg/dL, hemoglobin 11.6 g/dL, hematocrit 34.7%; Analysis of the life style of the two examples: Patients with advanced CKD, frequent office visits are permissive of living without dialysis. These can be viewed at a glance in Table 1.

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | |||

| First visit (2008) | Recent visit (2013) | First visit (2008) | Recent visit (2013) | |

| Age (yr) | 84 | 89 | 70 | 75 |

| Symptoms | None | None | None | None |

| Appetite | Good | Good | Good | Good |

| BP (mmHg) | 140/100 | 120/80 | 180/110 | 120/70 |

| Edema | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bun (mg/dL) | 49 | 61 | 28 | 35 |

| Scr (mg/dL) | 4.3 | 7.84 | 2.6 | 2.5 |

| eGFR (mL/min) | 10 | 5 | 26 | 24 |

| CO2 (mmol/L) | 26 | 21 | 29 | 27 |

| Hgb (g/dL) | 12 | 13.7 | 13 | 12 |

| Serum potassium (mmol/L) | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 4.5 |

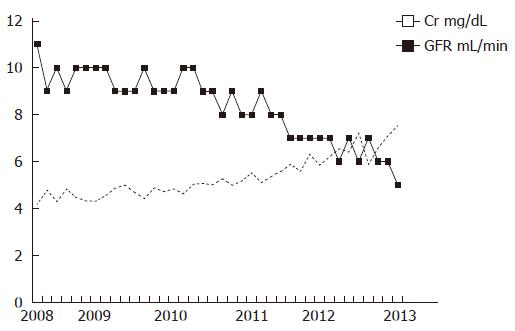

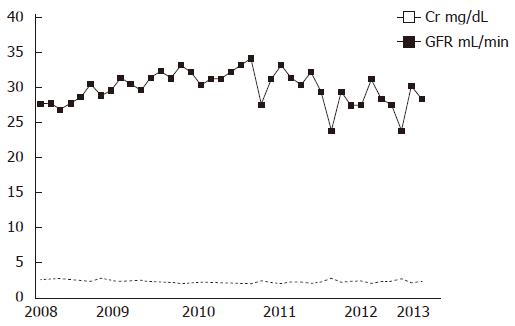

The renal function tests including serum creatinine and eGFR in patients 1 and 2 are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. In five years follow up; notably both patients are asymptomatic and living good albeit active lives. In both, BP is under perfect control and potassium control is normal. eGFR is decreased in both, more so in patient 1. The latter is probably more age related decrease rather than progression of CKD. Patient 1 is much older than patient 2. Neither is anemic by definition and required erythropoietic stimulating agent any time. Hypertension which is a most important risk factor in CKD progression is under superb control in both. In both patients, BP control is achieved with dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker (CCB) alone or a combination of CCB and beta blocker. A low dose loop diuretic and digoxin is used in patient 2 for pulmonary congestion and shortness of breath sometimes during the 5-year period. Overall, neither patient manifests symptoms or signs of fluid overload. Metabolic acidosis, hence hyperkalemia is prevented in both patients with liberal use of sodium bicarbonate and potassium exchange resin. The latter is used in sorbitol solution to avoid constipation.

Frequent office visits, for example every four to 8 wk, depending on the symptoms and laboratory findings of the previous office visit, is essential for (1) detection of unwarranted symptoms and signs at an early stage (2) maintaining the current well-being and steady state of BP control and fluid-electrolyte and acid-base status. Thus during each office visit a check list is completed of the following: (2) symptoms, (2) weight, (3) BP, (4) hemoglobin/hematocrit, (5) serum glucose: fasting and 2-h postprandial for patients with existing or new-onset diabetes, (6) renal function: BUN, serum creatinine, and eGFR, (7) electrolytes: Na+, K+, CO2; and calcium, phosphorous, uric acid and albumin, (8) intact PTH, (9) arterial blood gas to determine if low CO2 is due to metabolic acidosis or respiratory alkalosis, severity of metabolic acidosis, and PO2 in those with suspected congestive heart failure, (10) electrocardiogram in those with irregular heart rhythm, (11) review all medicines carefully. Discontinue any medicines suspected of causing renal function impairment and electrolyte imbalance.

Keep BP under control. Generally BP less than 140/80 mmHg is acceptable. BP less than 130/70 mmHg is probably ideal. BP of less than 120/70 mmHg may be harmful. In order to maintain BP at the levels already mentioned, it is very important to review BP medication at every visit and adjust as required. In resistant hypertension, a diuretic is a choice to reduce sodium (salt) and water retention which is common in CKD patients. Chlorthalidone is the diuretic of choice which predictably reduces elevated BP associated with salt and water retention. The dose of chlorthalidone is 25-50 mg once daily. Hydrochlorothiazide 25-50 mg once daily can be used instead of chlorthalidone. Loop diuretic such as furosemide 40 mg per oral once or twice daily or bumetanide 1 mg per oral once or twice daily is preferable if patient has evidence of congestive heart failure such as shortness of breath on exertion, pulmonary congestion in a chest X-ray or low PO2 in a blood gas analysis. Hyperkalemia and metabolic acidosis disorders are common and often severe, in those who are diet non-compliant, in particular consuming large meals or eating too many fruits. Prescription of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers by many prescribers with the obsessive idea of renal protection is a common cause of life threatening hyperkalemia (≥ 7.5 mmol/L) and severe metabolic acidosis. Use of over the counter drugs commonly non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain is also a common cause of hyperkalemia and metabolic acidosis.

Prevention of hyperkalemia is attainable but prevention of metabolic acidosis is more difficult to achieve. Since hyperkalemia is the result of transport of hydrogen ions, minimizing hydrogen build up is a key to prevention of both. Hydrogen ion build up can be minimized by controlling the source of hydrogen ion which is the food. A low protein diet (40-50 g) is beneficial in keeping BUN less than 50 mg/dL, reducing the risk of metabolic acidosis, hyperkalemia and hyperphosphatemia. A low protein diet supplies less sodium in the diet and is very useful in keeping BP under control and effective in minimizing fluid overload and CHF. However, low protein diet is non-palatable and adherence to this diet is uncommon. In addition, low protein diet is associated with malnutrition and low serum albumin which increase mortality. Thus protective effect of low protein diet cannot be relied upon; consequently therapeutic endeavor is essential. Protective effect of sodium bicarbonate therapy is documented by this author, and many other authors. Other authors have reported that sodium bicarbonate supplementation slows progression of CKD and improves nutritional status[6].

It should be noted that both patients in Table 1 are treated with sodium bicarbonate 650 mg tablet × 2, four times daily. Although CO2 in patient 1 is lower than that of patient 2 which is due to severity of renal dysfunction in patient 1, but serum albumin level is near normal and comparable. For prevention and treatment of hyperkalemia, sodium polysterene sulfonate (SPS) (Kayexalate®) is a good therapy. SPS dispensed in 30% sorbitol is very effective in keeping potassium under control. The usual dose is 5 g in 20 mL sorbitol once or twice daily. It may cause diarrhea which of course is the mechanism to enhance potassium excretion through the bowel when renal excretion of potassium is low. Effectiveness of kayexalate is increased when dispensed in sorbitol rather than dispensed in powder form, however, in the long run sorbitol is likely to increase blood glucose level. 9-α fludrocortisone (Florinef®), a synthetic analog of aldosterone in doses of 0.1-1 mg per oral once daily (usual dose is 0.1-0.3 mg/d) is also effective in enhancing renal excretion of potassium, but it is fraught with a risk of hypertension and CHF. Serum sodium is a good index of fluid balance. Rapid decrease in serum sodium may be significant for fluid overload and CHF. Attention must be paid in every office visit to hemoglobin level. Unchanged and normal or near normal hemoglobin (≥ 11 g/dL) is a good indirect evidence of stable renal function even if it is low. Rapid decrease of hemoglobin to less than 10 g/dL is a signal for rapidly deteriorating renal function, fluid overload, gastrointestinal bleeding or combination of any or all of these. Aspirin use should be avoided when hemoglobin is less than 11 g/dL and unstable. Phosphate control is a highly published item by the pharmaceutical industry. In the experience of the author, phosphate control has caused no problem to ensure well-being of the patients with CKD and maintain a dialysis free life.

Given the poor outcomes of many old, frail patients with multiple comorbid conditions on dialysis, there is a debate as to whether non-dialysis management as illustrated here would be more humane than dialysis management[7]. There are no studies done comparing survival or quality of life on conservative care and dialysis[8]. As described in the manuscript, conservative care should be given the highest priority in elderly people with advanced chronic renal failure. I believe that the evidence of the two patients shown here is important and should lead to a formal study.

P- Reviewers: Duan SB, Malatino LS, Sweet S S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Jayadevappa R, Chartre S. Patient centered care-a conceptual model and review of the state of the art. Open Health Serv Policy J. 2011;4:15-25. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wasson JH, Sauvigne AE, Mogielnicki RP, Frey WG, Sox CH, Gaudette C, Rockwell A. Continuity of outpatient medical care in elderly men. A randomized trial. JAMA. 1984;252:2413-2417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Williams GC, Freedman ZR, Deci EL. Supporting autonomy to motivate patients with diabetes for glucose control. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1644-1651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 729] [Cited by in RCA: 715] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | David RA, Rhee M. The impact of language as a barrier to effective health care in an underserved urban Hispanic community. Mt Sinai J Med. 1998;65:393-397. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Ware JE. Assessing the effects of physician-patient interactions on the outcomes of chronic disease. Med Care. 1989;27:S110-S127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | de Brito-Ashurst I, Varagunam M, Raftery MJ, Yaqoob MM. Bicarbonate supplementation slows progression of CKD and improves nutritional status. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2075-2084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 585] [Cited by in RCA: 558] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Knauf F, Aronson PS. ESRD as a window into America’s cost crisis in health care. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2093-2097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Brown EA. What can we do to improve quality of life for the elderly chronic kidney disease patient? Aging Health. 2012;8:519-524. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |