Published online Jul 12, 2015. doi: 10.5499/wjr.v5.i2.101

Peer-review started: November 26, 2014

First decision: January 20, 2015

Revised: March 13, 2015

Accepted: April 27, 2015

Article in press: April 29, 2015

Published online: July 12, 2015

Processing time: 223 Days and 16.4 Hours

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) presents with refractory, sterile, deep ulcers most often on the lower legs. Clinically, PG exhibits four types, i.e., ulcerative, bullous, pustular, and vegetative types. PG may be triggered by surgical operation or even by minor iatrogenic procedures such as needle prick or catheter insertion, which is well-known as pathergy. PG is sometimes seen in association with several systemic diseases including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), inflammatory bowel disease, hematologic malignancy, and Takayasu’s arteritis. In particular, various cutaneous manifestations are induced in association with RA by virtue of the activation of inflammatory cells (neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages), vasculopathy, vasculitis, drugs, and so on. Clinical appearances of ulcerative PG mimic rheumatoid vasculitis or leg ulcers due to impaired circulation in patients with RA. In addition, patients with PG sometimes develop joint manifestations as well. Therefore, it is necessary for not only dermatologists but also rheumatologists to understand PG.

Core tip: Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is occasionally seen in patients with systemic diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), inflammatory bowel disease, hematologic malignancy, and Takayasu’s arteritis. PG is sometimes precipitated by minor trauma or triggered by surgical operation or even by iatrogenic procedures such as needle prick or catheter insertion, which play a role as pathergy. Clinical appearances of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum mimic rheumatoid vasculitis or leg ulcers caused by impaired circulation in patients with RA. It is necessary for rheumatologists as well to understand pyoderma gangrenosum.

- Citation: Yamamoto T. Pyoderma gangrenosum: An important dermatologic condition occasionally associated with rheumatic diseases. World J Rheumatol 2015; 5(2): 101-107

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3214/full/v5/i2/101.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5499/wjr.v5.i2.101

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a refractory disease characterized by deep ulcers, predominantly in the lower extremities[1-4]. PG usually occurs in young to middle-aged, but sometimes involves elderly patients, with a slight predilection for females. The general incidence has been estimated to be 3 to 10 per million per year[5]. More recent studies have shown that the overall incidence was 6.3 (95%CI: 5.7-7.1) per million person-years in the United Kingdom[6]. PG is often triggered by iatrogenic or surgical procedures such as injection, needle prick, and catheter insertion, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), acute myeloid leukemia, and Takayasu’s arteritis (TA) through the therapies for primary diseases. RA presents with various cutaneous conditions, either specific or non-specific findings[7]. Among them, PG is the representative neutrophilic condition caused by activated neutrophil infiltration into the dermis. It is important for rheumatologists to know PG, because PG is sometimes misdiagnosed as rheumatoid vasculitis or leg ulcers due to impaired circulation, based on similar clinical appearances. This review provides current updates of the pathophysiology to better understand PG for especially rheumatologists.

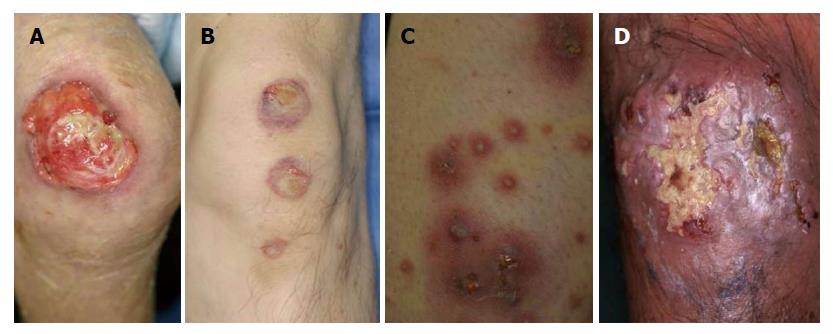

PG is clinically classified into 4 types, i.e., ulcerative, bullous, pustular and vegetative types. Ulcerative type PG is most common, which rapidly enlarges with central deep ulceration and undermined borders. The ulcerations are surrounded by raised edematous borders on the pretibial areas (Figure 1A). Initially, a small sterile follicular pustule arises, and rapidly forms abscess, ulcerated and spread outerwards. The surface is covered with necrotic tissues.

Bullous PG is relatively rare, and more than 30 cases of bullous PG have been so far reported[8]. This type is characterized by rapid development of vesicles and enlarging bullae with central necrosis and shallow erosions (Figure 1B). Previous reports indicate that extremities are the most frequently involved, and hematological malignancies, i.e., preleukemic conditions and leukemia, are mostly associated. In the majority of cases, development of bullous PG was related with the activity of gastrointestinal or hematological conditions.

Pustular PG is a rare type, and occasionally appears in association with other types. According to the frequent involvement of the lower extremities, pustules are often seen along with ulcerative lesion (Figure 1C). Additionally, pustules can be seen on the back, or scalp, as well.

Vegetative PG is a superficial, non-aggressive form with verrucous appearance (Figure 1D). Although several different clinical and histological features are proposed between PG and superficial granuloma pyoderma[9], vegetative type PG is nowadays considered to be the same as superficial granulomatous pyoderma[2]. Malignant pyoderma is a rare pyodermatous condition, which rapidly progresses and ulcerates, predominantly affecting the head and neck in young patients without associated systemic disorders[10]. Some of the reported cases present with similar clinical features to PG, whereas others not.

The most frequently involved site of PG is the lower legs, however, any other sites such as the face, trunk, and genital regions can also be involved. Genital PG is relatively few, with a male predominance[11]. It is important not to misdiagnose as decubitus. Rarely, PG occurs on the face, and also involves peripheral sites such as digits, ears and scalp[12] (Figure 2). Those cases may be considered to be peripheral PG. Periauricular PG is also rare, and several cases of auricular PG have been reported[13-15]. Peripheral PG involving fingers/toes, ears, and genital areas, should be widely recognized.

Other than the skin, several symptoms are occasionally seen associated with PG. Arthritis is the most common[16], followed by eye lesion and multiple organ involvement. Aseptic neutrophilic abscess is occasionally seen in the lung, kidney, liver, heart, central nervous system, and musculo-skeletal system, which disappear along with systemic steroid therapy.

Peristomal PG (PPG) is sometimes seen, mainly in patients with Crohn’s disease. PPG begins with painful tender or pustular lesions which form fistulous tracts or ulcerations spreading outward, occasionally without involvement of the mucocutaneous junction. Continual irritation, infection, increased pressure of stoma, or allergic reaction, as well as predisposition of parastomal skin of patients are suggested to induce PPG[17].

Superficial granulomatous pyoderma is a mild subtype of PG, which is slowly progressive and presents with superficial ulcers. Histologically, superficial granulomatous pyoderma shows a three-layered granuloma, such as inner neutrophils and necrosis surrounded by histiocytes and giant cells, with an outer layer of inflammatory cells. Apart from PG, superficial PG does not accompany other systemic disorders. Although superficial ulcers may respond to topical agents, some cases need systemic corticosteroids or disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs. Those refractory cases are sometimes called superficial granulomatous PG. This condition is considered to be similar to vegetative PG and also malignant pyoderma[2].

PG is rarely induced by drugs, i.e., iodide, bromide, isotretinoin, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. A few cases of propylthiouracil-induced PG have been reported in patients with positive ANCA[18-20]. By contrast, PR3-ANCA is extremely rare.

Pyodermatitis-pyostomatitis vegetans involves the oral cavity and skin, especially in patients with UC. This form may be a variant of pustular PG.

PG is sometimes associated with systemic diseases such as IBD, RA, TA, and hematologic disorders. Between rheumatic disease-associated and non-rheumatic disease-associated PG, there are no differences in the aspects of clinical features, pathogenesis, and response to therapy. Because PG is a relatively rare disease, case reports are the main and there are so far very few reports analyzing a significant number of cases. Neutrophils play an important role in the onset and perpetuation of RA, and activated neutrophils are recruited to the skin and induce various neutrophilic dermatosis such as PG, Sweet’s disease and erythema elevatum diutinum. PG is occasionally seen in relation with the severity and activity of RA. Very recently, a cohort study has been published which analyzed a large database of IBD[21]. The ratio of PG was 1.9% among patients with IBD, and more than half of the patients had active bowel disease in relation with the episodes of PG. TA is characterized by stenosis or occlusion affecting mainly the aorta and its branches in young women. Several kinds of cutaneous manifestations are occasionally seen in association with TA, with representative lesions such as erythema nodosum and PG. To date, the association of PG and TA has not been frequently reported[22]. PG occurring in patients with TA usually involves the upper limbs, followed by the scalp, face, neck, trunk, buttocks, and pubic region, in addition to the lower limbs[23]. Inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor - α (TNF-α), are considered to play an important role in the pathogenesis of TA. Recent studies have shown that TNF-α targeted therapies are effective for both TA[24] and PG[25], suggesting possible pathogenic similarities between these disorders. In addition, hematologic malignancies such as malignant lymphoma and leukemia, systemic lupus erythematosus, chronic hepatitis, and primary biliary cirrhosis are associated.

Autoinflammatory disease is characterized by hyperreactvation of the innate immune system, some of which show skin, joint, and eye manifestations. PG may be included in idiopathic febrile syndromes of autoinflammatory diseases, along with fever, systemic symptoms (i.e., anemia, aseptic arthritis, liver dysfunction, lymphoadenopathy), and increased levels of acute-phase protein. Not all of the cases of PG mean autoiinflammatory diseases, however, cases accompanied with other symptoms may be considered to represent autoinflammatory disorders. pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, pyogenic arthritis syndrome is caused by mutations in the PSTPIP1 gene on chromosome 15. pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, suppurative hidradenitis syndrome lacks pyogenic arthritis, and genetic analysis revealed frequent CCTG repeat in the PSTPIP1 promoter[26]. Very recently, pyoderma gangrenosum, acne conglobate, supprative hidradenitis, axial spondylarthritis syndrome and pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, psoriasis, arthritis, suppurative hidradenitis (PAPASH) syndrome have been proposed[27,28].

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is caused by follicular occlusion by infundibular hyperkeratinization and dilatation. HS is occasionally associated with IBD and more recently developed as one of the major skin manifestations of autoinflammatory syndrome. Recent advances in the pathogenesis of HS suggest the significant role of IL-23/Th17 signaling pathway, reduced innate defense antimicrobial peptides, and elevated levels of TNF-α[29,30].

Psoriasis is immunologically mediated by aberrant, skin-directed T cells belonging to Th1/Th17 subset. In a large review of more than 100 patients with PG, 11 (11%) patients had psoriasis[31]. Fewer number of cases of PG associated with psoriatic arthritis have also been reported[32,33].

Palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP) presents with sterile pustules on the palms and soles, with a predilection for females. PPP is a disease close to psoriasis, and the IL-23/IL-17 inflammatory pathway has recently been suggested to be important also in PPP. IL-23 expression is enhanced in the lesional skin[34], and IL-17 is detected close to or in the acrosyringium[35]. IL-8 has been considered to play a key role in the neutrophil accumulation in the epidermis, but recent findings suggest that IL-17 may also play an important role, because IL-17 promotes neutrophil migration via the release of CXC chemokines[36]. IL-17 and IL-22 are increased in the peripheral blood of patients with PPP[37]. Although the simultaneous co-existence of PPP and PG in a single patient is rare, several cases have been reported[38], which suggest an etiological link between those disorders.

Histological features are not pathognomonic, and dense neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltration is seen in the whole dermis. In the upper edematous dermis, a number of neutrophils and lymphocytes infiltrate, and neutrophilic abscess was located in the mid- to lower dermis with the basophilic collagen bundles accompanied by histiocytes as well as plasma cells. There are no features of vasculitis. Histological features of bullous PG show subepidermal edema with numerous neutrophil infiltration. Histological features of pustular type shows dense neutrophil infiltration in the upper to mid-dermis. Because the diagnosis of PG is made clinically, exclusion of other disorders presenting ulcers is necessary.

Although PG is a neutrophilic disorder, not only neutrophils but also a number of CD3-positive T cells infiltrate in the lesional skin[39], which suggests that T cells play an important role in the induction of PG, via T cell-derived cytokines and chemokines. Histological features of PG have shown that neutrophil recruitment was predominant in the ulcerative wound bed, whereas in the wound edge, activated T cells and macrophages were abundant and play a role as effector cells to ulcer formation[40]. IL-8 has been implicated to play an important role in neutrophil recruitment in the lesional skin. TNF-α induces IL-8 production by peripheral mononuclear cells[41]. Also, therapies targeting TNF-α result in beneficial effects on refractory PG[42,43], suggesting a crucial role of TNF-α in the pathogenesis of PG. TNF-α enhances vascular permeability in endothelial cells[44] as well as endothelial barrier dysfunction, which may be relevant to bullous formation of PG. TNF-α plays an important role in IBD, whereas role of TNF-α in hematological malignancy is unclear. The etiology of bullous PG in hematological conditions needs further studies.

In addition, Th17 cells promote neutrophil-mediated inflammation. IL-17 activates the endothelium to lead to neutrophil infiltration in a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent manner[45]. In addition, IL-17 and TNF-α enhance endothelial expression of neutrophil chemokines, i.e., CXCL1, CXCL2 and CXCL5, leading to leukocyte migration[46]. Recently, increased expression of IL-23 was found in the lesional skin of PG, and targeting therapy of IL-12/IL-23 p40 was effective[47], suggesting that IL-23 may play a pathogenic role in PG.

It is well-known that surgical operation and minor trauma precipitate PG. There are many reports of PG occurring at percutaneous surgical sites, such as breast surgery, pacemaker implantation, splenectomy, hysterectomy, endoscopic tube insertion, cholecystectomy, and cesarean delivery[22,48]. Similar cases have been reported which were triggered even by less invasive iatrogenic procedures such as injection, needle prick, and catheter insertion, in patients with underlying systemic diseases. Such phenomena are called pathergy, which means hyper-reactivity of the skin in response to even minor trauma. Because the majority of patients with PG have systemic disorders, PG should be correctly and widely recognized, not misdiagnosed as infectious conditions, by the doctors belonging to other departments than dermatology. These results suggest that pathergy reaction is implicated as a triggering role in PG in susceptible patients, even without systemic diseases. Pathergy can be seen in about 20% of cases of PG[2]. The etiology of pathergy is still unknown, however, activated neutrophils recruited to the injured skin, via an aberrant immune response to minor trauma, defective cell-mediated immunity, aberrant integrin oscillations on neutrophils and abnormal neutrophil tracking, have been speculated.

Skin diseases exhibiting refractory ulcers, due to infection, vascular insufficiency, vasculitis, and malignancy should be differentiated. Especially in cases affecting patients with RA, rheumatoid vasculitis or leg ulcers due to impaired circulation should be carefully differentiated.

Cutaneous manifestations of granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis) present with purpura, ulcer, hemorrhagic bullae, livedo reticularis, and subcutaneous nodules. Histologically, specific skin lesions show granulomatous vasculitis. Sometimes, PG-like ulcerative lesions occur in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis[49-51], which are sometimes reported as malignant pyoderma.

Cutaneous cryptococcosis presents with various features such as papules, pustules, nodules, granulomas, abscesses, subcutaneous swelling, cellulitis-like erythema, erysipelas, and ulcers. A few cases with clinical features mimicking PG have been reported[52,53].

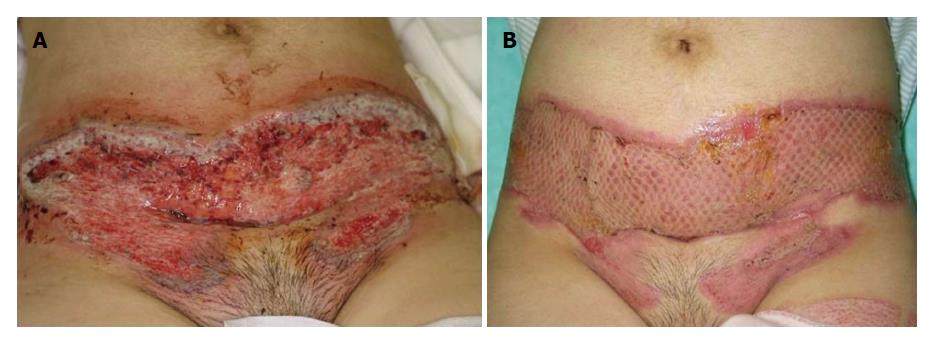

Occasionally, PG is improved only by topical immunotherapies, such as corticosteroids, tacrolimus, and pimecrolimus[47,54], however, the first line for the therapy of PG is systemic corticosteroids. For steroid-resistant cases, other immunosuppressive and immunomodulatory drugs, such as cyclosporine, thalidomide, tacrolimus, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, and recently biologics are also used[25,55]. In particular, anti-TNF-α therapies result in beneficial effects on refractory PG. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial have demonstrated a superior effect of infliximab for PG[56]. Also, a number of case reports have demonstrated that biologics targeting TNF-α and IL-12/23 p40 are effective for PG[47,57-59]. Surgical therapy is also adopted at the last step, with the aid of prednisolone use (Figure 3). In contrast to dramatic effect of biologics, PG is paradoxically induced by biologics, in rare cases[60-62].

To diagnose PG properly, it is important to lay stress on clinical features and to exclude other disorders exhibiting ulcers, because the histologic features are not diagnostic. At present, there are no diagnostic criteria. However, several proposals have recently been shown[4,63], which are expected to be of great help for correct diagnosis. Furthermore, although there are many single case reports, very few cohort studies or comparative studies among underlying systemic diseases have been done. To perform those studies, collaboration of different departments is necessary in the future project.

P- Reviewer: Agarwal V, Cavallasca JA, Rothschild BM S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | Crowson AN, Mihm MC, Magro C. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:97-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ruocco E, Sangiuliano S, Gravina AG, Miranda A, Nicoletti G. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an updated review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1008-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 343] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wollina U. Pyoderma gangrenosum--a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jackson JM, Callen JP. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an expert commentary. Exp Rev Dermatol. 2006;1:391-400. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Powell FC, Schroeter AL, Su WP, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of 86 patients. Q J Med. 1985;55:173-186. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Langan SM, Groves RW, Card TR, Gulliford MC. Incidence, mortality, and disease associations of pyoderma gangrenosum in the United Kingdom: a retrospective cohort study. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:2166-2170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yamamoto T. Cutaneous manifestations associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2009;29:979-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Takenoshita H, Yamamoto T. Bullous pyoderma gangrenosum in patients with ulcerative colitis and multiple myeloma. Our Dermatol Online. 2014;5:310-311. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Thami GP, Kaur S, Punia RS, Kanwart AJ. Superficial granulomatous pyoderma: an idiopathic granulomatous cutaneous ulceration. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:159-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cardinali C, Giomi B, Caproni M, Fabbri P. Guess what! Malignant pyoderma responding to cyclosporine. Eur J Dermatol. 2001;11:595-596. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Satoh M, Yamamoto T. Genital pyoderma gangrenosum: report of two cases and published work review of Japanese cases. J Dermatol. 2013;40:840-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ohashi T, Miura T, Yamamoto T. Auricular pyoderma gangrenosum with penetration in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2014;Jun 10; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Iijima S, Ogawa T, Nanno Y, Tsunoda T, Kudoh K. Pyoderma gangrenosum first presenting as a recalcitrant ulcer of the ear lobe. Eur J Dermatol. 2003;13:606-609. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Sarma N, Bandyopadhyay SK, Boler AK, Barman M. Progressive and extensive ulcerations in a girl since 4 months of age: the difficulty in diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:48-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ben Chaabane N, Hellara O, Ben Mansour W, Ben Mansour I, Melki W, Loghmeri H, Safer L, Bdioui F, Saffar H. Auricular pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Crohn’s disease. Tunis Med. 2012;90:414-415. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Al Ghazal P, Herberger K, Schaller J, Strölin A, Hoff NP, Goerge T, Roth H, Rabe E, Karrer S, Renner R. Associated factors and comorbidities in patients with pyoderma gangrenosum in Germany: a retrospective multicentric analysis in 259 patients. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lyon CC, Smith AJ, Griffiths CE, Beck MH. Peristomal dermatoses: a novel indication for topical steroid lotions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43:679-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Darben T, Savige J, Prentice R, Paspaliaris B, Chick J. Pyoderma gangrenosum with secondary pyarthrosis following propylthiouracil. Australas J Dermatol. 1999;40:144-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hong SB, Lee MH. A case of propylthiouracil-induced pyoderma gangrenosum associated with antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. Dermatology. 2004;208:339-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Seo JW, Son HH, Choi JH, Lee SK. A Case of p-ANCA-Positive Propylthiouracil-Induced Pyoderma Gangrenosum. Ann Dermatol. 2010;22:48-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Weizman AV, Huang B, Targan S, Dubinsky M, Fleshner P, Kaur M, Ippoliti A, Panikkath D, Vasiliauskas E, Shih D. Pyoderma Gangrenosum among Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Descriptive Cohort Study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:125-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hiraiwa T, Furukawa H, Yamamoto T. Pyoderma gangrenosum triggered by surgical procedures in patients with underlying systemic diseases. Our Dermatol Online. 2014;5:432-433. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Ujiie H, Sawamura D, Yokota K, Nishie W, Shichinohe R, Shimizu H. Pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Takayasu’s arteritis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2004;29:357-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Comarmond C, Plaisier E, Dahan K, Mirault T, Emmerich J, Amoura Z, Cacoub P, Saadoun D. Anti TNF-α in refractory Takayasu’s arteritis: cases series and review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11:678-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ahronowitz I, Harp J, Shinkai K. Etiology and management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13:191-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Braun-Falco M, Kovnerystyy O, Lohse P, Ruzicka T. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, and suppurative hidradenitis (PASH)--a new autoinflammatory syndrome distinct from PAPA syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:409-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bruzzese V. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne conglobata, suppurative hidradenitis, and axial spondyloarthritis: efficacy of anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2012;18:413-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Garzorz N, Papanagiotou V, Atenhan A, Andres C, Eyerich S, Eyerich K, Ring J, Brockow K. Pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, psoriasis, arthritis and suppurative hidradenitis (PAPASH)-syndrome: a new entity within the spectrum of autoinflammatory syndromes? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;Jul 28; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Schlapbach C, Hänni T, Yawalkar N, Hunger RE. Expression of the IL-23/Th17 pathway in lesions of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:790-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wolk K, Warszawska K, Hoeflich C, Witte E, Schneider-Burrus S, Witte K, Kunz S, Buss A, Roewert HJ, Krause M. Deficiency of IL-22 contributes to a chronic inflammatory disease: pathogenetic mechanisms in acne inversa. J Immunol. 2011;186:1228-1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Binus AM, Qureshi AA, Li VW, Winterfield LS. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a retrospective review of patient characteristics, comorbidities and therapy in 103 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165:1244-1250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Smith DL, White CR. Pyoderma gangrenosum in association with psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:1258-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Spangler JG. Pyoderma gangrenosum in a patient with psoriatic arthritis. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14:466-469. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Lillis JV, Guo CS, Lee JJ, Blauvelt A. Increased IL-23 expression in palmoplantar psoriasis and hyperkeratotic hand dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:918-919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Hagforsen E, Hedstrand H, Nyberg F, Michaëlsson G. Novel findings of Langerhans cells and interleukin-17 expression in relation to the acrosyringium and pustule in palmoplantar pustulosis. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:572-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Laan M, Cui ZH, Hoshino H, Lötvall J, Sjöstrand M, Gruenert DC, Skoogh BE, Lindén A. Neutrophil recruitment by human IL-17 via C-X-C chemokine release in the airways. J Immunol. 1999;162:2347-2352. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Murakami M, Hagforsen E, Morhenn V, Ishida-Yamamoto A, Iizuka H. Patients with palmoplantar pustulosis have increased IL-17 and IL-22 levels both in the lesion and serum. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:845-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ohtsuka M, Yamamoto T. Rare association of pyoderma gangrenosum and palmoplantar pustulosis: a case report and review of the previous works. J Dermatol. 2014;41:732-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Brooklyn TN, Williams AM, Dunnill MG, Probert CS. T-cell receptor repertoire in pyoderma gangrenosum: evidence for clonal expansions and trafficking. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:960-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Marzano AV, Cugno M, Trevisan V, Fanoni D, Venegoni L, Berti E, Crosti C. Role of inflammatory cells, cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases in neutrophil-mediated skin diseases. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;162:100-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Andoh A, Ogawa A, Kitamura K, Inatomi O, Fujino S, Tsujikawa T, Sasaki M, Mitsuyama K, Fujiyama Y. Suppression of interleukin-1beta- and tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced inflammatory responses by leukocytapheresis therapy in patients with ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:1150-1157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Stichweh DS, Punaro M, Pascual V. Dramatic improvement of pyoderma gangrenosum with infliximab in a patient with PAPA syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2005;22:262-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Fonder MA, Cummins DL, Ehst BD, Anhalt GJ, Meyerle JH. Adalimumab therapy for recalcitrant pyoderma gangrenosum. J Burns Wounds. 2006;5:e8. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Brett J, Gerlach H, Nawroth P, Steinberg S, Godman G, Stern D. Tumor necrosis factor/cachectin increases permeability of endothelial cell monolayers by a mechanism involving regulatory G proteins. J Exp Med. 1989;169:1977-1991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Roussel L, Houle F, Chan C, Yao Y, Bérubé J, Olivenstein R, Martin JG, Huot J, Hamid Q, Ferri L. IL-17 promotes p38 MAPK-dependent endothelial activation enhancing neutrophil recruitment to sites of inflammation. J Immunol. 2010;184:4531-4537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Griffin GK, Newton G, Tarrio ML, Bu DX, Maganto-Garcia E, Azcutia V, Alcaide P, Grabie N, Luscinskas FW, Croce KJ. IL-17 and TNF-α sustain neutrophil recruitment during inflammation through synergistic effects on endothelial activation. J Immunol. 2012;188:6287-6299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Guenova E, Teske A, Fehrenbacher B, Hoerber S, Adamczyk A, Schaller M, Hoetzenecker W, Biedermann T. Interleukin 23 expression in pyoderma gangrenosum and targeted therapy with ustekinumab. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:1203-1205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Kikuchi N, Hanami Y, Miura T, Kawakami Y, Satoh M, Ohtsuka M, Yamamoto T. Pyoderma gangrenosum following surgical procedures. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:346-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Jacob SE, Martin LK, Kerdel FA. Cutaneous Wegener’s granulomatosis (malignant pyoderma) in a patient with Crohn’s disease. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:896-898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Szõcs HI, Torma K, Petrovicz E, Hársing J, Fekete G, Kárpáti S, Horváth A. Wegener’s granulomatosis presenting as pyoderma gangrenosum. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:898-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Kouba DJ, Mimouni D, Ha CT, Nousari CH. Limited Wegener’s granulomatosis manifesting as malignant pyoderma with corneal melt. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:902-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Massa MC, Doyle JA. Cutaneous cryptococcosis simulating pyoderma gangrenosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:32-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Jasch KC, Hermes B, Scheller U, Harth W. Pyoderma gangrenosumlike primary cutaneous cryptococcosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:76-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Kontos AP, Kerr HA, Fivenson DP, Remishofsky C, Jacobsen G. An open-label study of topical tacrolimus ointment 0.1% under occlusion for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1383-1385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Miller J, Yentzer BA, Clark A, Jorizzo JL, Feldman SR. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review and update on new therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:646-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MG, Shetty A, Bowden JJ, Williams JD, Griffiths CE, Forbes A, Greenwood R, Probert CS. Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55:505-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 402] [Cited by in RCA: 426] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Juillerat P, Christen-Zäch S, Troillet FX, Gallot-Lavallée S, Pannizzon RG, Michetti P. Infliximab for the treatment of disseminated pyoderma gangrenosum associated with ulcerative colitis. Case report and literature review. Dermatology. 2007;215:245-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Mooij JE, van Rappard DC, Mekkes JR. Six patients with pyoderma gangrenosum successfully treated with infliximab. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:1418-1420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Heffernan MP, Anadkat MJ, Smith DI. Adalimumab treatment for pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:306-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Le Cleach L, Moguelet P, Perrin P, Chosidow O. Is topical monotherapy effective for localized pyoderma gangrenosum? Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:101-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Kikuchi N, Hiraiwa T, Ohashi T, Hanami Y, Satoh M, Takenoshita H, Yamamoto T. Pyoderma gangrenosum possibly triggered by adalimumab. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22:804-805. [PubMed] |

| 62. | Brunasso AM, Laimer M, Massone C. Paradoxical reactions to targeted biological treatments: A way to treat and trigger? Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:183-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Hadi A, Lebwohl M. Clinical features of pyoderma gangrenosum and current diagnostic trends. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:950-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |