Published online Jun 22, 2013. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v3.i2.25

Revised: April 4, 2013

Accepted: April 13, 2013

Published online: June 22, 2013

AIM: To investigate adherence to medical regimen and predictors for non-adherence among children with cancer in Egypt.

METHODS: We administered two study specific questionnaires to 304 parents of children diagnosed with cancer at the Children’s Cancer Hospital in Cairo, Egypt, one before the first chemotherapy treatment and the other before the third. The questionnaires were translated to colloquial Egyptian Arabic, and due, to the high illiteracy level in Egypt an interviewer read the questions in Arabic to each parent and registered the answers. Both questionnaires consisted of almost 90 questions each. In addition, a Case Report Form was filled in from the child’s medical journal. The study period consisted of 7 mo (February until September 2008) and we had a participation rate of 97%. Descriptive statistics are presented and Fisher’s exact test was used to check for possible differences between the adherent and non-adherent groups. A P-value below 0.05 was considered significant. Software used was SAS version 9.3 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States).

RESULTS: Two hundred and eighty-one (90%) parents answered the second questionnaire, regarding their child’s adherence behaviour. Approximately two thirds of the children admitted to their third chemotherapy treatment had received medical recommendations upon discharge from the first or second chemotherapy treatment (181/281, 64%). Sixty-eight percent (123/181) of the parents who were given medical recommendations reported that their child did not follow the recommendations. Two main predictors were found for non-adherence: child resistance (111/123, 90%) and inadequate information (100/123, 81%). In the adherent group, 20% of the parents (n = 12/58) reported trust in their child’s doctor while 14 percent 8/58 reported trust in the other health-care professionals. Corresponding numbers for the non-adherent group are 8/123 (7%) for both their child’s doctor and other health-care professionals. Almost all of the parents expressed a lack of optimism towards the treatment (116/121, 96%), yet they reported an intention to continue with the treatment for two main reasons, for the sake of their child’s life (70%) (P = 0.005) and worry that their child would die if they discontinued the treatment (81%) (P < 0.0001).

CONCLUSION: Non-adherence to medical regimen is common among children diagnosed with cancer in Egypt, the main reasons being child resistance and inadequate information.

Core tip: Ensuring adherence to a prescribed medication regimen is a complex problem, even in parts of the world where studies have been made. Such studies have not been made in the Arab World. Research has established that a holistic approach is essential if adherence is to be improved. We know that patient-physician communication and psychological factors bearing on behaviour are important. This is shown by our study at the Children’s Cancer Hospital in Egypt; two thirds of the children did not follow the medication regimen upon discharge. Parents reported that their children resisted taking the medication and information given was inadequate.

- Citation: El Malla H, Ylitalo Helm N, Wilderäng U, El Sayed Elborai Y, Steineck G, Kreicbergs U. Adherence to medication: A nation-wide study from the Children’s Cancer Hospital, Egypt. World J Psychiatr 2013; 3(2): 25-33

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v3/i2/25.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v3.i2.25

Patient adherence is a crucial factor contributing to the efficacy of a therapeutic regimen[1]. Despite the dangerous nature of paediatric cancers, 50%-55% of chronically ill paediatric patients are non-adherent[2,3] and 10%-50% of cancer-sick children fail to adhere to the oral medication regimen[1,4]. Hence, non-adherence to prescribed medical regimen is considered the “leading cause of treatment failure across most childhood conditions”[2]. Even when faced with a potentially life threatening illness, it cannot be assumed that patients will adhere to the prescribed medication regimen. There is some evidence that adherence is influenced by age and certain behavioural characteristics[5] but the area of adherence is quite complex especially in the Arab societies where both the concept of adherence and awareness of its importance are as yet foreign.

Adherence to (or compliance with) a medication plan interrelates with a large number of medical/treatment, personal, social factors as well as relationship with the health-care system[6,7]. Adherence is “¡the extent to which a person’s behaviour, taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider”[2]. This definition implies that the patient has a choice and that both patients and providers mutually establish treatment goals[8]. It also places a well-defined responsibility on the health-care professionals to clearly explain the treatment options and to establish solid communication with the child and the parent. The emotional well-being of the patient is equally important in treatment adherence as it shapes and guides the action and behaviour of the patient[9].

Non-adherence to a medical regimen is a concern in the treatment of paediatric malignancies, not least in the developing countries[10], since it can have significant adverse health outcomes in children and adolescents with cancer[4,8]. Refraining from taking or incorrectly taking cancer medications can bring about serious health and economic outcomes for the individual child and the wider society[11,12]. Increased health-care costs (extended treatment, additional doctor visits, changed prescriptions), and the development of drug-resistance are common outcomes of non-adherence[2,10,12,13]. In addition, non-adherent patients report poorer quality of life, more illnesses, increased hospitalization and increased morbidity and mortality[2,12,13].

Failure to adhere has been described as “the best documented but least understood health-related behaviour”[14]. Factors contributing to treatment adherence are poorly understood, but the physician-patient interaction is one factor that is known to affect patient adherence[14]. If the patients understand their physicians they are more likely to modify their behaviour according to the physician’s recommendation and to follow the suggested treatment schedule[9], a prerequisite for obtaining decreased mortality[13]. Parent’s lack of understanding the diagnosis and treatment, their concerns about treatment effectiveness and the side effects of treatment and even their denial of the diagnosis are factors that have all been linked to poor adherence[4]. Disagreement with or low trust in the clinicians, lack of adequate medical information, and the desire to manage the situation independent of the medical profession (self-efficacy) are predictors for non-adherence in patients[15].

In a study addressing trust in health-care and children’s physicians in the paediatric oncology setting, El Malla et al[16] found that provision of information is a strong predictor of trust in health-care. In particular, being provided with information about the disease and treatment in a kind and thoughtful way and being met with care were predictors of trust. Parents who felt they were given the opportunity to communicate with the child’s physician, and who felt they had the chance to express thoughts and concerns at the start of treatment were more likely to trust the medical caregivers. Furthermore, parents who reported that they felt that their emotional and intellectual needs were met to at least a moderate degree at the start of treatment were more likely to report trust[16].

Locus of control has been previously addressed in the literature in relation to adherence. Partridge and colleagues suggest that the individual’s feeling of control over his or her illness may influence adherence to medication. They hypothesise that the individual who believes he or she has greater influence over the situation would be more likely to adhere to the medication regimen whereas individuals with a fatalistic view of the situation would be less adherent[17]. In a review article by Zygmunt et al[18] patient and family interventions dealing with promotion of adherence to medication have been applied in the field of psychiatry in several studies where the patient and families, together or separately, receive psycho-education along with behavioural and problem-solving strategies. This further emphasizes the integral part of the field of psychology and psychiatry in the promotion of cancer treatment where the behavioural component and supportive services together with psycho-education have been shown in several studies to promote adherence to medication[8,11,17,18]. Nonetheless, behavioural interventions have been shown in a number of studies to be superior in promoting adherence in comparison to psycho-educational techniques[8,18].

We know little about the extent of adherence to chemotherapy treatment in children, teenagers and adolescents in the Arab region. Our aim was to investigate adherence to the medical recommendations that are provided upon discharge to children newly diagnosed with cancer at the Children’s Cancer Hospital in Cairo, Egypt. Furthermore, we wanted to investigate predictors for adherence and non-adherence.

The study population comprised all parents (n = 313) of children newly diagnosed with cancer admitted to receive their first chemotherapy treatment cycle at the Children’s Cancer Hospital in Cairo, Egypt, during a study period of 7 mo (February until September 2008).

We included every parent (one parent per child) admitted with his/her child to the hospital, newly diagnosed and about to receive the first chemotherapy cycle. This was our baseline. The same parents were subsequently asked to fill in the second questionnaire (Pre-3) upon admission to the third chemotherapy cycle. We excluded parents of children admitted for surgery and radiation only. All parents were approached prior to the child’s initial treatment at the daycare center or at the inpatient ward, depending on where the child was scheduled to receive the treatment. Aside from the most updated and advanced free-of-charge treatment provided and the compensated transportation to/from hospital, the Children’s Cancer Hospital also provides the child, upon discharge, with all of the required medications (dose adjusted) needed during the home stay. These factors could be considered as controlled confounders. The treatment provided at the hospital is in agreement with the international standards and WHO with a few modifications to suit the specific setting of the hospital patients.

Due to the high illiteracy level in Egypt, the study team decided to have an interviewer administer the questionnaire. The interviewer read the questions and possible answer categories to the parents and filled in their replies in the questionnaire. The study was approved by the regional ethical review board at the University of Gothenburg and the Children’s Cancer Hospital research committee. All patients provided informed oral consent.

Working in accordance with the methodology of study preparation established at the Division of Clinical Cancer Epidemiology, a methodology described in detail in several articles[16,19-23], we developed two study-specific questionnaires. The study preparation included conducting in-depth interviews (n = 29) with parents of children newly diagnosed with and undergoing cancer treatment at the paediatric oncology wards in three governmental hospitals in Cairo, Egypt. Thereafter, to ensure that all questions and response alternatives were fully understood the way we intended, face-to-face validation was conducted (in spring 2007) with 28 parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer at the peadiatric oncology wards in three governmental hospitals in Cairo, Egypt. The final questionnaires were validated in a subsequent pilot study (in autumn 2007) of 54 parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer. During this study, we estimated a likely participation rate and checked whether some questions were left unanswered. None of the parents declined participation; thus, we proceeded to the main study.

Both questionnaires (“Pre-1” prior to chemotherapy treatment cycle 1 and “Pre-3” prior to chemotherapy treatment cycle 3) were translated from English into colloquial Arabic and consisted of almost 90 questions each. The questionnaires were marked with a serial number on the back and could only be decoded for identity by the researcher. In addition, a Case Report Form (CRF) was filled in from the child’s medical journal. The CRF contained the following information: child’s name, address, name of parent, age, gender, length, weight, diagnosis, date of interview, scheduled chemotherapy treatments, medicine received and dose. The two questionnaires were divided as follows: Pre-1: socio-demographic data, cancer diagnosis, family history, the amount of information provided about the disease, treatment, and most common side effects of treatment, hospital stay experience, diagnosis disclosure, communication with physicians and health-care professionals, and psychosocial and emotional experiences. Pre-3: reasons for delay to medical treatment, information provided by health-care professionals, investigations, hospital stay experience, next treatment cycle attendance, adherence to medical treatment at hospital and home, psychosocial and emotional experiences, and trust in physician and other health-care professionals as well as the medical care.

Questions of relevance for this paper, which are extracted from “Pre-3”, were if the parents had received recommendations upon discharge, whether or not the recommendations had been followed, and if the parent found the given recommendations relevant and manageable. If any of the recommendations had not been followed, the parents were given five options to explain why they were not followed. Answer alternatives were: “Yes” and “No”.

An additional question addressed if the parents planned to have their child attend the next treatment cycle, and the reasons for planning or not planning to attend. The answer alternative to the second question included seven options with one option left blank for the parent to fill in if their reasons did not fit with any of those given. Furthermore, parents were asked if they were involved in the decision-making of the child’s treatment and hospital care, and if they trusted the health-care professionals or not. The answer alternatives for these questions were: “None”, “A little”, “Moderate”, “Much”.

Data were manually entered into Epidata version 2.0 and 20% of the questionnaires were re-entered to check accuracy. Descriptive statistics are presented as frequencies and percentages. For calculating P-values, we used Fisher’s exact test, considering a P-value below 0.05 as indicating statistically significance. In calculating relative risks with corresponding 95%CIs, a log-binomial regression model was performed. Software used was SAS software version 9.3 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States).

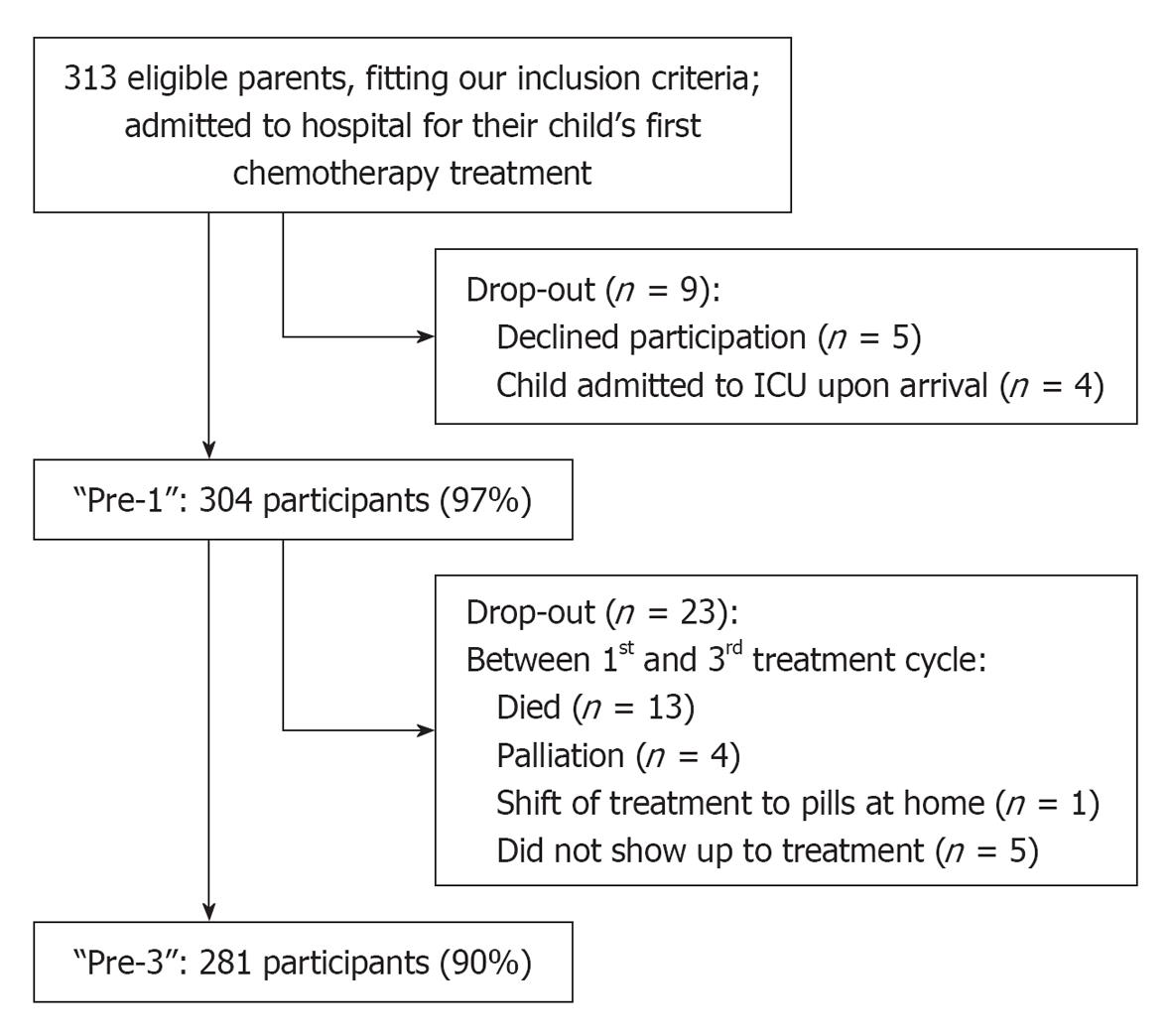

Among the 313 eligible parents, 304 (97%) answered the first (Pre-1), and 281 (90%) answered the second questionnaire (Pre-3) from which we have extracted data for use in this paper (Figure 1). Basic characteristics of the 281 children and parents who answered the second questionnaire (Pre-3) are shown in Table 1.

| Characteristics | |

| Primary caregiver of the child | |

| Mother | 17 (6) |

| Father | 30 (11) |

| Both parents | 234 (83) |

| Participants accompanying/staying with the child at the hospital | |

| Mother | 228 (81) |

| Father | 47 (17) |

| Both parents | 2 (1) |

| Other | 4 (1) |

| Child’s gender | |

| Male | 165 (59) |

| Female | 116 (41) |

| Child’s age (yr) | |

| 0-4 | 119 (42) |

| 5-8 | 59 (21) |

| 9-15 | 89 (32) |

| 16-18 | 14 (5) |

| Mother’s level of education | |

| No education | 98 (35) |

| Primary/preparatory | 54 (19) |

| Secondary | 49 (17) |

| Institute-diploma | 48 (17) |

| University | 32 (11) |

| Father’s level of education | |

| No education | 91 (32) |

| Primary/preparatory | 39 (14) |

| Secondary | 65 (23) |

| Institute-diploma | 53 (19) |

| University | 29 (10) |

| Not stated | 4 (1) |

| Mother’s occupation | |

| Housewife | 254 (90) |

| Labourer | 9 (3) |

| Employee | 17 (6) |

| Own business | 1 (< 1) |

| Father’s occupation | |

| Unemployed | 15 (5) |

| Labourer | 186 (66) |

| Employee | 60 (21) |

| Own business | 14 (5) |

| Not stated | 6 (2) |

| Residential region | |

| Urban | 89 (32) |

| Rural | 185 (66) |

| Abroad | 7 (2) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Leukaemia | 128 |

| Pre-B ALL | 77 |

| Pre-T ALL | 25 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 24 |

| JMML | 2 |

| Lymphomas | 52 |

| Non-Hodgkin | 39 |

| Hodgkin | 13 |

| Brain tumor | 16 |

| Medulloblastom | 8 |

| PNET | 3 |

| Other | 5 |

| Neuroblastoma | 29 |

| Sarcomas | 30 |

| Ewing sarcoma | 16 |

| Osteosarcoma | 6 |

| Rhabdomyosarcomas | 8 |

| Wilms’ tumor | 4 |

| Hepatoblastoma | 6 |

| Germ cell tumor | 6 |

| Other | 10 |

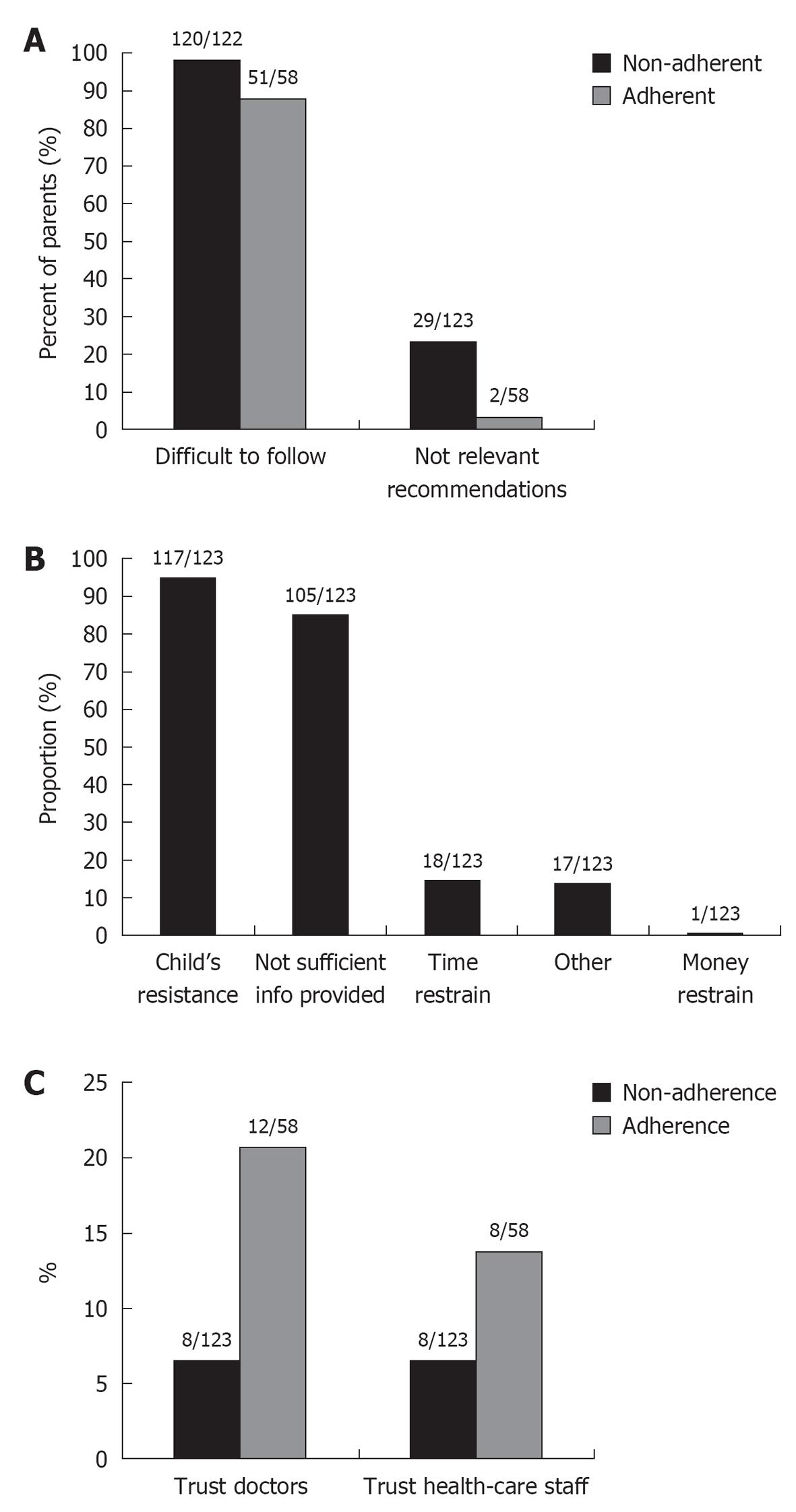

In the studied population, which had a total of 281 parents after drop out between the two questionnaires; 64% (n = 181/281) of the parents had reported that they received medicine to take home upon discharge between the first and/or second chemotherapy treatments. No statistically significant differences were found between the two groups of parents who followed (n = 58/181, 32%) and who did not follow (n = 123/181, 68%) the medication except for an increased adherence among children of educated mothers (P = 0.017). Among the adherent children’s parents, 88% (n = 51/58) reported difficulties following the recommendations, whereas almost all parents (n = 56/58, 97%) considered the recommendations as relevant (Figure 2A).

According to the parents’ reports, 90% (n = 117/123) of the children who received medical recommendation upon discharge refused to take the provided treatment while at home (Figure 2B). Furthermore, 85% (n = 105/123) of these parents reported that the information provided upon discharge was insufficient (Figure 2B). Almost all parents of the non-adherent children (n = 120/122, 98%) reported difficulties following the recommendations although two thirds (n = 94/123, 76%) found the recommendations relevant (Figure 2A).

In the adherent group one out of five parents (n = 12/58) reported trust in their child’s doctor while 8/58 (14%) reported trust in the other health-care professionals (Figure 2C). Corresponding numbers for trust among non-adherent were 8/123 (7%) for both the child’s doctor and other health-care professionals.

Nearly all parents (n = 122/123) who received medical recommendations upon discharge but who were non-adherent reported an intent to attend their child’s next chemotherapy treatment cycle, although the majority in this group did not consider the treatment to be of any use, n = 180/277 (65%). After adjusting for seven independent variables to explain the parent’s intentions to pursue the next chemotherapy treatment cycle, two independent variables were left to explain that outcome; doing so for the sake of their child’s life (70%) (P = 0.005) and worry that their child would die if they discontinued the treatment (81%) (P < 0.0001) (Table 2).

| Characteristics | Non-adherent (n = 123) | Adherent(n = 58) | P-value1 |

| Optimistic regarding the results so far | 5 (4) | 8 (14) | 0.028 |

| Hope treatment will prove to be effective | 46 (38) | 31 (53) | 0.054 |

| Believe the treatment is effective | 2 (2) | 2 (4) | 0.593 |

| Pursue for child’s life, although treatment is of no use | 86 (70) | 28 (48) | 0.005 |

| Scared that child will die if discontinued treatment | 99 (81) | 27 (47) | < 0.0001 |

| Pursue according to religious beliefs, though treatment is of no use | 69 (57) | 30 (53) | 0.632 |

| Other | 3 (2) | 3 (5) | 0.387 |

No parent had been involved in the decision making regarding the child’s treatment or hospital care and 94% (n = 266/281) of the parents reported that they had no or little knowledge about their child’s disease and treatment. Nine independent psycho-social and emotional predictors were identified and included in a model. The risk of not having the psycho-social and emotional needs met in the non-adherent group was almost double the risk in the adherent group. Furthermore, the non-adherent group of parents reports the situation as being more than five times more difficult to manage than do those who adhere (Table 3).

| Predictors | Adherent | Non-adherent |

| How do you perceive your current situation? | ||

| Moderately manageable/manageable | 7 (87) | 1 (13) |

| RR (95%CI) | 1.0 (Reference) | |

| Unmanageable/little manageable | 51 (30) | 122 (70) |

| RR (95%CI) | 5.64 (0.89-35) | |

| Some parents have reported experience of loneliness at the hospital; does this correspond with your experience? | ||

| None/a little/moderate | 14 (61) | 9 (39) |

| RR (95%CI) | 1.0 (Reference) | |

| Much | 44 (28) | 114 (72) |

| RR (95%CI) | 1.84 (1.1-3.1) | |

| Do you feel you are in need of sharing your emotional burdens and strains with someone? | ||

| None/a little/moderate | 18 (46) | 21 (54) |

| RR (95%CI) | 1.0 (Reference) | |

| Much | 40 (28) | 102 (72) |

| RR (95%CI) | 1.33 (0.98-1.8) | |

| Do you have someone to share your emotional burdens and strains with? | ||

| None | 9 (50) | 9 (50) |

| RR (95%CI) | 1.0 (Reference) | |

| A little/moderate/much | 49 (30) | 114 (70) |

| RR (95%CI) | 1.4 (0.87-2.24) | |

| Have you perceived the health-care staff to be sensitive to your emotional needs? | ||

| Moderate/much | 8 (62) | 5 (38) |

| RR (95%CI) | 1.0 (Reference) | |

| None/a little | 50 (30) | 118 (70) |

| RR (95%CI) | 1.83 (0.9-3.6) | |

| Have you perceived the health-care staff to be sensitive to your intellectual needs? | ||

| Moderate/much | 6 (60) | 4 (40) |

| RR (95%CI) | 1.0 (Reference) | |

| None/a little | 52 (30) | 119 (70) |

| RR (95%CI) | 1.7 (0.80-3.7) | |

| Do you consider that the health-care staff has been kind to you? | ||

| Moderate/much | 10 (67) | 5 (33) |

| RR (95%CI) | 1.0 (Reference) | |

| None/a little | 48 (29) | 118 (71) |

| RR (95%CI) | 2.13 (1.03-4.4) | |

| Do you consider that the health-care staff has met you with care? | ||

| Moderate/much | 9 (64) | 9 (36) |

| RR (95%CI) | 1.0 (Reference) | |

| None/a little | 49 (29) | 118 (71) |

| RR (95%CI) | 1.97 (0.97-4.0) | |

| Do you consider that the health-care staff is thoughtful with you? | ||

| Moderate/much | 5 (71) | 2 (29) |

| RR (95%CI) | 1.0 (Reference) | |

| None/a little | 53 (30) | 121 (70) |

| RR (95%CI) | 2.43 (0.75-7.88) | |

A majority of parents of children newly diagnosed with cancer report that their child did not follow the prescribed medical regimen given upon discharge from the Children’s Cancer Hospital, Egypt.

In our study, the child’s resistance was the main predictor for non-adherence to prescribed medical regimen. Our findings are supported by Kondryn et al[1] who found that 27%-63% of adolescent patients did not follow the prescribed oral treatment. Age appears to play a role in adherence-related behaviours in children with cancer[4,6]. As children grow, behavioural concerns related to adherence may become dominant for some children who may actively refuse medication[4]. Also, as children become more autonomous, adherence tends to become more difficult to maintain[13]. Adolescents usually strive for autonomy and independence and usually have limited ability to understand the consequences of their actions, and thus they become frustrated with parental authority and the limitation of their illness, all which may lead to non-adherence[4]. Furthermore, adolescents’ oppositional behaviour and wanting to be like their healthy peers has been documented as a reason for non-adherence[13]. Side effects of treatment could be another reason; yet, we have no data from our study to support this.

Previous studies have found that poor adherence among children is mainly due to their own and their parents’ lack of knowledge and understanding about the disease and its treatment[2,4]. In our study, we found that inadequate information provided to the parent was an important predictor for non-adherence to the prescribed medical regimen. The communication between the health-care providers and the patient is an important factor for adherence[10]. When patients understand their physicians they tend to follow their treatment regimen and modify their behaviour to a larger degree[24]. Furthermore, in a study made by Safran et al[25], trust was found to be a key element in the patient-physician relationship and older patients who trust their physician were among those who complied best with the medical regimen. We have previously reported a lack of trust towards the child’s physicians and the health care professionals in our study group[16]. We can now show that adherence to prescribed medical regiment was more commonly reported in parents who trusted the physicians and the health-care professionals (Figure 2C). Furthermore, Perez-Carceles and co-workers conducted a cross-sectional survey at an urban Spanish university hospital of 300 patients admitted to the emergency department during a period of 3 mo. They found a significant relation between perceived information to the patient and his/her satisfaction with the care[26]. These data are supported by our previous findings that parental satisfaction depend upon the quality of communication with health-care professionals[16]. Taking time to understand the child and family builds trust, leading to increased reporting of the actual reason for the visit and influences treatment adherence and outcome, adaptation to illness, and bereavement[16]. Clearly, improved communication will enhance patient outcomes and satisfaction[16,27-36]. Nonetheless, several studies within the field of psychology and psychiatry have observed that psycho-education and the provision of information are most effective when aligned with behavioural and problem-solving strategies to enhance and promote adherence[17,18].

We did not find any association between region (as a surrogate to ethnicity) or any other socio-demographic factors (shown in Table 1) and non-adherence to prescribed medical regimen. Thus, these factors probably did not confound our reported associations.

Epidemiological methods in study design and data interpretation were applied in accordance with the hierarchical step-model for causation of bias[19]. We believe that our extensive preparatory process decreases the risk of measurement errors[16]. The general strengths of the present study include: a fairly high number of participants, a high participation rate, as well as a two-stage follow up, stage 1 at the time of the first chemotherapy treatment and stage 2 at the time of the third treatment. By utilizing two study-specific questionnaires, developed after conducting extensive in-depth interviews and careful face-to-face validations, we may likely have reduced the risk for both kinds of measurement errors as well as interviewer-induced bias. It is important to note that parents were provided with the prescribed, dose-adjusted medication upon discharge, which excludes lack of money or other variables as a reason for non-adherence. To avoid reporting chance results indicating an effect, we formulated four hypotheses before the study began. In addition to that, our study group was not aware of these hypotheses.

Nevertheless, there are limitations to our study. First, we have no data concerning the child’s perceived feelings or perception of the disease and treatment and/or the side effects of the treatment that may vary from a treatment to another. Second, we do not know the reasons why the child refuses the medication. Third, it is unclear to what extent our findings may be representative for the region or to other populations in the Arab World as the hospital environment and treatment provided at Children’s Cancer Hospital are very advanced and in agreement with the international treatments protocols which may not be the situation in other governmental hospital in Egypt or the Arab World.

Despite the limitations noted, we believe that our study makes an important contribution since non-adherence to medical regimen is an important issue in dealing with childhood malignancies; and it occurs to a large extent in our study group. This report indicates that child resistance and inadequate information to the parents were the two main predictors for non-adherence to prescribed medical regimen among children treated for malignancies at Children’s Cancer Hospital, Egypt.

Adherence to oral chemotherapy in childhood malignancies is a complex, multidimensional behaviour that requires understanding on the part of the parent and child and also requires that they correctly carry out complex instructions from the health-care provider about a variety of medications. These instructions take into account factors including the time of the day when the medication is to be administered, whether the medication must be administered by restricting intake of certain products such as dairy products or must be taken when nothing is being eaten. All these factors may require frequent dose adjustments in response to blood counts, infections, clinical course, or changes in weight or body surface area. Therefore, adherence involves not only a willingness to follow the prescribed regimen over a prolonged, defined period, but also the cognitive competence and psychomotor skills to carry out the process.

Working together in partnership with a parent and health-care provider may optimize the child’s adherence to oral chemotherapy regimen. Nonetheless, further research aimed at identification of specific barriers to adherence, appreciating the magnitude of the problem and the reasons for failure to adhere to the medication regimen as well as development of interventional strategies to facilitate the process of adherence need to be pursued, despite the barriers.

The study group would like to thank all the participating parents in the study. Special thanks also to Professor Dr. Sherife Abulnaga, whom without the study would not have been possible to conduct. Also, a special appreciation to Professor Dr. Samir Abulmagd, Dr. Osama Refaat, Dr. Mohamad Nasr, Dr. Mohamad Ezzat, Dr. Mohamad Alshami and RN Patricia Pruden for their invaluable support during the data collection.

Non-adherence to a medication regimen is a significant concern in paediatric oncology not least in the developing countries, since it can have significant adverse health outcomes in children and adolescents with cancer. Despite the dangerous nature of paediatric cancers, 10%-50% of cancer-sick children fail to adhere to the oral medication regimen

Increased health-care costs (extended treatment, additional doctor visits, changed prescriptions), and the development of drug-resistance are common outcomes of non-adherence. In addition, non-adherent patients report poorer quality of life, more illnesses, increased hospitalization time and increased morbidity and mortality.

Failure to adhere has been described as “the best documented but least understood health-related behaviour”. Factors contributing to treatment adherence are poorly understood, but the physician-patient interaction is one factor that is known to affect patient adherence. If the patients understand their physicians they are more likely to modify their behaviour according to the physician’s recommendation and to follow the suggested treatment schedule, a prerequisite for obtaining a successful effect from the drugs and an increased quality of life and in many treatments, decreased mortality. Authors know little about the extent of adherence to chemotherapy treatment in children, teenagers and adolescents in the Arab region. Their aim was to investigate adherence to the medical recommendations that are provided upon discharge to children newly diagnosed with cancer. They also wanted to investigate the degree of non-adherence and possible predictors.

Child resistance and shortage of information provided to the parents were the two main predictors for children’s non-adherence to medication at home, as reported by the parents.

Adherence to (or compliance with) a medication plan interrelates with a large number of medical and social factors. Adherence is “…the extent to which a person’s behaviour - taking medication, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes, corresponds with agreed recommendations from a health care provider”.

This is a nation-wide prospective study following patients on two different occasions right after cancer diagnosis. The results suggest that non-adherence is found on a large scale among the children diagnosed with cancer. The children are newly diagnosed, which means that they will have at least months or years of treatment, thus, adherence is crucial.

P- Reviewers Contreras CM, Szekely A S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Kondryn HJ, Edmondson CL, Hill J, Eden TO. Treatment non-adherence in teenage and young adult patients with cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:100-108. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 95] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rapoff MA. Adherence to pediatric medical regimens. 2nd ed. New York: Springer 2010; . [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Geffken GR, Keeley ML, Kellison I, Storch EA, Rodrigue JR. Parental adherence to child psychologists' recommendations from psychological testing. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2006;37:499-505. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Landier W. Age span challenges: adherence in pediatric oncology. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2011;27:142-153. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kennard BD, Stewart SM, Olvera R, Bawdon RE, hAilin AO, Lewis CP, Winick NJ. Nonadherence in adolescent oncology patients: preliminary data on psychological risk factors and relationships to outcome. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2004;11:31-39. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 128] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tebbi CK, Cummings KM, Zevon MA, Smith L, Richards M, Mallon J. Compliance of pediatric and adolescent cancer patients. Cancer. 1986;58:1179-1184. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Ruddy K, Mayer E, Partridge A. Patient adherence and persistence with oral anticancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:56-66. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 406] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 428] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Patel MX, David AS. Medication adherence: predictive factors and enhancement strategies. Psychiatry. 2004;3:41-44. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dimatteo MR. The role of effective communication with children and their families in fostering adherence to pediatric regimens. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55:339-344. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 105] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dawood OT, Izham M, Ibrahim M, Palaian S. Medication compliance among children. World J Pediatr. 2010;6:200-202. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dolder CR, Lacro JP, Leckband S, Jeste DV. Interventions to improve antipsychotic medication adherence: review of recent literature. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:389-399. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 135] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Griffith R. Improving patients’ adherence to medical regimens. Practice Nurse. 2006;31:21-26. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Ou HT, Feldman SR, Balkrishnan R. Understanding and improving treatment adherence in pediatric patients. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2010;29:137-140. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kato PM, Cole SW, Bradlyn AS, Pollock BH. A video game improves behavioral outcomes in adolescents and young adults with cancer: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e305-e317. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. Why don’t patients take their medicine Reasons and solutions in psychiatry. Adv Psychiatr Treat. 2007;13:336-346. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 115] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | El Malla H, Kreicbergs U, Steineck G, Wilderäng U, Elborai Yel S, Ylitalo N. Parental trust in health care--a prospective study from the Children’s Cancer Hospital in Egypt. Psychooncology. 2013;22:548-554. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Partridge AH, Avorn J, Wang PS, Winer EP. Adherence to therapy with oral antineoplastic agents. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:652-661. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 402] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zygmunt A, Olfson M, Boyer CA, Mechanic D. Interventions to improve medication adherence in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1653-1664. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 338] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 295] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Steineck G, Hunt H, Adolfsson J. A hierarchical step-model for causation of bias-evaluating cancer treatment with epidemiological methods. Acta Oncol. 2006;45:421-429. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 83] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdóttir U, Steineck G, Henter JI. A population-based nationwide study of parents’ perceptions of a questionnaire on their child’s death due to cancer. Lancet. 2004;364:787-789. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdóttir U, Onelöv E, Henter JI, Steineck G. Talking about death with children who have severe malignant disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1175-1186. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 331] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bergmark K, Avall-Lundqvist E, Dickman PW, Henningsohn L, Steineck G. Vaginal changes and sexuality in women with a history of cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1383-1389. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 522] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 488] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Steineck G, Helgesen F, Adolfsson J, Dickman PW, Johansson JE, Norlén BJ, Holmberg L. Quality of life after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:790-796. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 539] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 480] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Travaline JM, Ruchinskas R, D’Alonzo GE. Patient-physician communication: why and how. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2005;105:13-18. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Safran DG, Taira DA, Rogers WH, Kosinski M, Ware JE, Tarlov AR. Linking primary care performance to outcomes of care. J Fam Pract. 1998;47:213-220. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Perez-Carceles MD, Gironda JL, Osuna E, Falcon M, Luna A. Is the right to information fulfilled in an emergency department Patients’ perceptions of the care provided. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16:456-463. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Levetown M. Communicating with children and families: from everyday interactions to skill in conveying distressing information. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1441-e1460. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 271] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Landier W. Adherence to oral chemotherapy in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: an evolutionary concept analysis. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38:343-352. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Stewart JL, Pyke-Grimm KA, Kelly KP. Parental treatment decision making in pediatric oncology. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2005;21:89-97; discussion 98-106. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Mack JW, Wolfe J, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Communication about prognosis between parents and physicians of children with cancer: parent preferences and the impact of prognostic information. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5265-5270. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 230] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Zwaanswijk M, Tates K, van Dulmen S, Hoogerbrugge PM, Kamps WA, Bensing JM. Young patients’, parents’, and survivors’ communication preferences in paediatric oncology: results of online focus groups. BMC Pediatr. 2007;7:35. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 101] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hesse BW, Nelson DE, Kreps GL, Croyle RT, Arora NK, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2618-2624. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 992] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 886] [Article Influence: 49.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Lannen P, Wolfe J, Mack J, Onelov E, Nyberg U, Kreicbergs U. Absorbing information about a child’s incurable cancer. Oncology. 2010;78:259-266. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Mack JW, Grier HE. The Day One Talk. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:563-566. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 66] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Mack JW, Hilden JM, Watterson J, Moore C, Turner B, Grier HE, Weeks JC, Wolfe J. Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9155-9161. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 220] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Byrne MK, Deane FP. Enhancing patient adherence: outcomes of medication alliance training on therapeutic alliance, insight, adherence, and psychopathology with mental health patients. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2011;20:284-295. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |