Published online Dec 9, 2014. doi: 10.5497/wjp.v3.i4.193

Revised: September 22, 2014

Accepted: October 1, 2014

Published online: December 9, 2014

Processing time: 171 Days and 0.6 Hours

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) almost recurs after liver transplantation for HCV-related liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma. Management of HCV recurrence after liver transplantation is challenging because the traditional interferon-based therapy is often patient-intolerable and inducing cytopenia, and dose reduction is needed. The response rate in liver recipients is inferior to those of chronic HCV infection. About 5 percent of liver recipients receiving interferon-based therapy would develop immune-mediated graft injury and may need retransplantation. Recent advances of anti-HCV therapy for chronic HCV infection has evolutionary changing the schema from interferon-based, to interferon-free, and even to ribavirin -free, all oral combinations for pan-genotypes. Management of HCV recurrence after liver transplantation is currently evolving too and promising results will soon come to the stage. This “fast-track” concise review focuses on the issues relevant to HCV recurrence after liver transplantation and provides up-to-date information of the trend of the management. A real-world case demonstration of management was presented here to illustrate the potential complications of anti-HCV therapy after liver transplantation.

Core tip: Management of hepatitis C virus (HCV) recurrence after liver transplantation used to be a bothering issue due mostly to the interferon-based therapy. Current available data from treatment of chronic HCV infection shows promising results of interferon-free, or even ribavirin-free, pan-genotypic, all oral medications will soon reform the treatment of HCV recurrence after liver transplantation.

- Citation: Ho CM, Hu RH, Lee PH. Perspective of antiviral therapeutics for hepatitis C after liver transplantation. World J Pharmacol 2014; 3(4): 193-198

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3192/full/v3/i4/193.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5497/wjp.v3.i4.193

Hepatitis C-related liver cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma is the main indication of liver transplantation worldwide[1-4]. Almost all recipients experiences posttransplant recurrence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and some degrees of long-term graft injury[5,6]. Although hepatitis C is a potentially curable disease because it is caused by an RNA flavivirus with 6 major genotypes[4], and, unlike hepatitis B virus which integrates its DNA into host DNA genome and causes viral clearance difficult, therapeutic outcomes were inferior in liver recipients compared to patients of chronic HCV infection[7].

Ongoing evolutionary positive results in “general” (non-recipient) population shed promising lights on HCV liver recipients who are still struggling to suffer from the recurrence. The aim of this concise review is to illustrate the current and, more importantly, future pictures of the anti-HCV therapeutics after liver transplantation for non-hepatologists by summarizing a great varieties of reviews and articles. Detailed or extensive dissections of single agents are beyond the scope of this fast-track review and will be suggested to references.

Early experiences showed that after liver transplantation for HCV-related cirrhosis, persistent HCV infection can cause severe graft damage, and such damage is more frequent in patients infected with HCV genotype 1b than with other genotypes[8].

As more experiences accumulated around the world, the natural history of HCV is accelerated after liver transplantation with 20%-40% progressing to cirrhosis within 5 years[9-12]. Evidence of markers and risk factors, including clinical, serum, histopathological, or donor-related, to early predict this group of patients is summarized well in Howell et al[5] and Mariño et al[13] review and is still being identified. Crespo et al[6] proposed simplified algorithm, combining risk factors (old donors, female recipients, diabetes mellitus, cytomegalovirus infection and corticosteroid boluses) and non-invasive liver stiffness measurement, for management of HCV recurrence after liver transplantation and further consolidated the timing for antiviral intervention.

The primary goal in this scenario is prevention of graft loss from fibrosis progression[12]. Viral load does not correspond to graft injury[14]. Clinicians should note that progression of fibrosis is occasionally observed even in patients who responded to treatment; in these cases, progression may be related to other factors, such as smoldering rejection, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, other graft-related issues, or older donor or patient age[14]. About 5% of liver recipients receiving interferon-based regimens would develop rejection or graft fibrosis, in the absence of HCV[14]. They could be related to interferon-induced innate alloimmune response or fluctuation of immunosuppressant levels via drug interactions[15-18].

Once graft injury progresses irreversibly, either through fibrosis due to HCV recurrence or through therapeutic-induced, immune-mediated injury, retransplantation is often the only option of treatment[19,20]. Patient and graft survival rates after retransplantation in these circumstances, however, are inferior to those after primary liver transplantation[19] although it seems no different compared to those of retransplantation due to other reasons[20].

HCV was first isolated and identified in 1989[21]. Lai et al[22] pioneer study found that interferon-based therapy increased the sustained virologic response and thereafter was considered as the standard of care for HCV treatment. Interferon-based therapy augments the innate immune response to cure the virus[23]. Ribavirin synergistically increase the interferon effect through NK cell activation[24]. As the 3D crystalized structure of HCV was identified, more and more targets disclosed and large upcoming amounts of new drugs designed to achieve better effect[25,26]. Non-structural (NS)3/4A protease inhibitors were added to the interferon-based regimen and increased the sustained virological response (SVR) further[25].

The effective therapy against chronic HCV infection has improved dramatically recently, with expected SVR rates of near 75% in all previously untreated patients and the current treatment guidelines was summarized by Gane et al[12].

Recently, NS 5B polymerase inhibitor further raised the response rate substantially and open the era of interferon-free, all oral, regimens[25]. NS 5B and NS 5A fixed, once daily combination further suggest the possibility of ribavirin-free regimens in the near future[27,28]. Shorter treatment course and pan-genotypic response, in previous treatment failure or cirrhotic patients make anti-HCV treatment revolutionary[27-29]. The evolutionary trend of anti-HCV therapy was nicely presented in Heim’s work[25].

Table 1 summarized the major anti-HCV therapeutic agents, mode of actions, and major side effects. High cost will be the major issue of anti-HCV therapy in the world instead[30]. In the future, the indication for ribavirin would be limited only to non-nucleotide-based combinations or failure of other oral combination[7,31].

| Category | Specific target | Mechanism of action | Major side-effect |

| Interferon α | Host hepatocytes and immune cells | Enhance host immune response | Flu-like symptoms |

| Ribavirin (nucleoside inhibitor) | Nucleoside guanosine analogue | Stop viral RNA synthesis and viral mRNA capping Enhance interferon response | Cytopenia |

| DAA | |||

| Protease inhibitor (NS3 inhibitor or NS3/4A inhibitor) | NS 3 serine protease ± NS4A cofactor | Inhibit cleavage of the HCV proteins from the polyprecursor | Transfusion-dependent anemia; drug interaction with calcineurin inhibitors |

| HCV polymerase inhibitor (NS 5B inhibitor) | NS 5B protein (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase) | Inhibit HCV replication | Minimal |

| NS 5A replication complex inhibitor | NS 5A protein (protein for viral RNA replication and inteferon-resistance) | Stop viral RNA replication | Minimal |

Interferon-based regimens after liver transplantation achieved 30% SVR in liver recipients, with higher rates achievable in patients with non-1 genotypes[32,33]. A lot of HCV liver recipients, however, are rejected for the regimens from the start or early in the course of treatment because of the side effect intolerance. In fact, the most negative predictor for viral response is lack of tolerability from pegylated interferon/ribavirin-more than 80% of patients dose reduce and almost 30% cease therapy because of adverse effects[12]. These results highlight the critical need for better tolerated and more efficacious HCV therapies for HCV transplant recipients[12].

Interferon-based, NS 3A/4A added regimens after liver transplantation could be further increased the SVR to 50%[34]. Discontinuation rates were still observed high and over one third of patients need blood transfusion[12]. In addition, antiviral therapy utilizing boceprevir in liver transplant recipients requires close monitoring of cyclosporine (5-fold) or tacrolimus (70-fold increase) due to the enzyme inhibition of the cytochrome P450 3A[12].

A case report of the HCV liver recipient with good virological response using NS 5B inhibitor show promise of translating the success in “general” HCV population to HCV liver recipients[35]. Sarkar et al[31] reported preliminary, multi-center, promising results of sofosbuvir and ribavirin for post-transplant HCV recurrence (more than 80% had HCV genotype 1) in the Liver Meeting 2013. They found a rapidly decline of HCV after starting therapy, and over 70% of 40 recipients had SVR 4 wk after completing treatment[36,37]. Only 2 (5%) had side effects that led to treatment discontinuation[36,37]. These studies had actively formulating the future all-oral treatment regimens in HCV liver recipients.

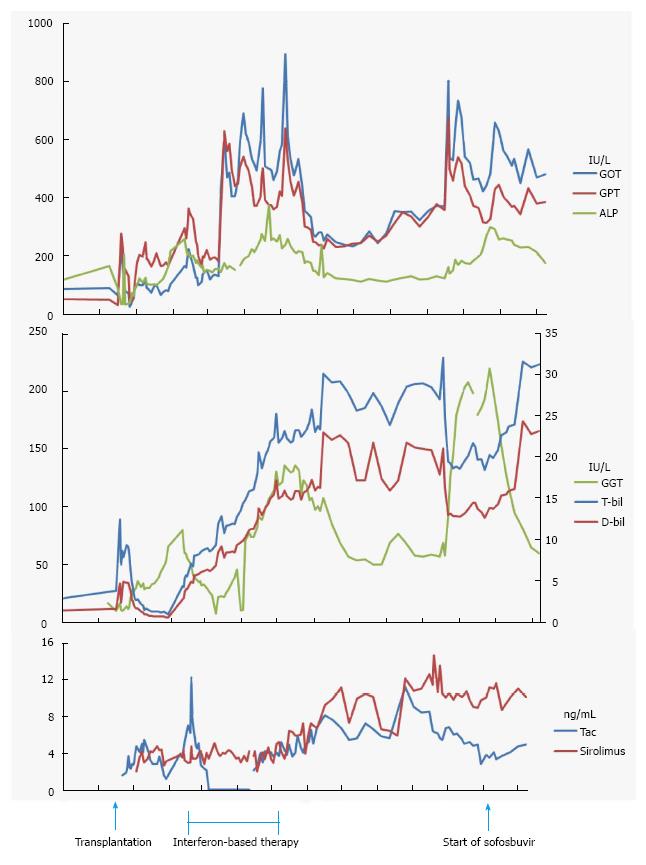

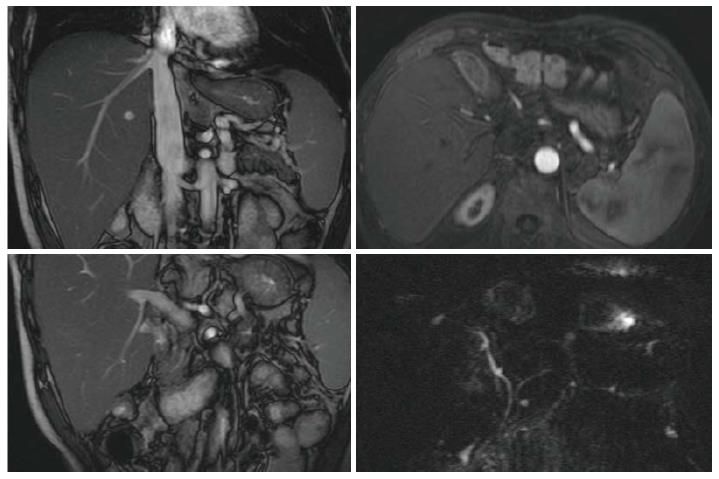

A 59 year-old man, received liver transplantation for HCV-related liver cirrhosis, was referred for prolonged and progressive jaundice since 2 mo following liver transplantation. Serial liver biopsies showed chronic hepatitis C and serum viral load was 5.8 × 106 IU/mL with the genotype 1B. Interferon-based therapy was initiated soon but lasted for 3 mo because of patient intolerance. The viral load was 1.3 × 104 IU/mL at this time. Jaundice, however, was progressive. Laboratory data of liver profiles were shown in Figure 1. Image survey showed no evidence of vascular or biliary complications (Figure 2). Immunosuppressant regimens were tacrolimus-based initially, withdrawal transiently for the threat of drug-related cholestasis, and followed by re-initiation. The serum levels of immunosuppressant (tacrolimus and sirolimus) were shown in Figure 1. Interferon-based therapy with add-in sofosbuvir were restarted 9 mo after liver transplantation. Ribavirin and sofosbuvir were used 3 wk later without interferon because of the patient intolerance. Serum viral load dropped dramatically to undetectable 3 mo after the use of sofosbuvir, 11 mo after transplantation and remained thereafter. The latter serial liver biopsies (from 5 mo to 11 mo after liver transplantation), however, showed first acute rejection, and chronic rejection later. Steroid bolus therapy was not responsive. Liver re-transplantation was suggested.

In summary, with the rapid advances of anti-viral therapy in HCV hepatitis, the prognosis of HCV liver recipients is expected to improve greatly once the all oral, interferon-free, ribavirin-free regimens come to the stage of the standard of care with reasonable cost.

P- Reviewer: Jr JDA, Simkhovich BZ S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Chinnadurai R, Velazquez V, Grakoui A. Hepatic transplant and HCV: a new playground for an old virus. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:298-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Williams R. Global challenges in liver disease. Hepatology. 2006;44:521-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 526] [Cited by in RCA: 546] [Article Influence: 28.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lee MH, Yang HI, Lu SN, Jen CL, You SL, Wang LY, Wang CH, Chen WJ, Chen CJ. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection increases mortality from hepatic and extrahepatic diseases: a community-based long-term prospective study. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:469-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 389] [Cited by in RCA: 426] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Roche B, Samuel D. Hepatitis C virus treatment pre- and post-liver transplantation. Liver Int. 2012;32 Suppl 1:120-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Howell J, Angus P, Gow P. Hepatitis C recurrence: the Achilles heel of liver transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2014;16:1-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Crespo G, Mariño Z, Navasa M, Forns X. Viral hepatitis in liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1373-1383.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liang TJ, Ghany MG. Current and future therapies for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1907-1917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gane EJ, Portmann BC, Naoumov NV, Smith HM, Underhill JA, Donaldson PT, Maertens G, Williams R. Long-term outcome of hepatitis C infection after liver transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:815-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 787] [Cited by in RCA: 736] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Garcia-Retortillo M, Forns X, Feliu A, Moitinho E, Costa J, Navasa M, Rimola A, Rodes J. Hepatitis C virus kinetics during and immediately after liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2002;35:680-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 422] [Cited by in RCA: 381] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ballardini G, De Raffele E, Groff P, Bioulac-Sage P, Grassi A, Ghetti S, Susca M, Strazzabosco M, Bellusci R, Iemmolo RM. Timing of reinfection and mechanisms of hepatocellular damage in transplanted hepatitis C virus-reinfected liver. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:10-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gane EJ, Naoumov NV, Qian KP, Mondelli MU, Maertens G, Portmann BC, Lau JY, Williams R. A longitudinal analysis of hepatitis C virus replication following liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:167-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 383] [Cited by in RCA: 352] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gane EJ, Agarwal K. Directly acting antivirals (DAAs) for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in liver transplant patients: “a flood of opportunity”. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:994-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mariño Z, Mensa L, Crespo G, Miquel R, Bruguera M, Pérez-Del-Pulgar S, Bosch J, Forns X, Navasa M. Early periportal sinusoidal fibrosis is an accurate marker of accelerated HCV recurrence after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2014;61:270-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nair SP. Management of hepatitis C virus infection in liver transplant recipients. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2012;8:56-59. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Shaked A. The interrelation between recurrent hepatitis C, alloimmune response, and immunosuppression. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:1329-1331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nellore A, Fishman JA. NK cells, innate immunity and hepatitis C infection after liver transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:369-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Levitsky J, Fiel MI, Norvell JP, Wang E, Watt KD, Curry MP, Tewani S, McCashland TM, Hoteit MA, Shaked A. Risk for immune-mediated graft dysfunction in liver transplant recipients with recurrent HCV infection treated with pegylated interferon. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1132-1139.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Selzner N, Guindi M, Renner EL, Berenguer M. Immune-mediated complications of the graft in interferon-treated hepatitis C positive liver transplant recipients. J Hepatol. 2011;55:207-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Carrión JA, Navasa M, Forns X. Retransplantation in patients with hepatitis C recurrence after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2010;53:962-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Maggi U, Andorno E, Rossi G, De Carlis L, Cillo U, Bresadola F, Mazzaferro V, Risaliti A, Bertoli P, Consonni D. Liver retransplantation in adults: the largest multicenter Italian study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science. 1989;244:359-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4996] [Cited by in RCA: 4657] [Article Influence: 129.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lai MY, Kao JH, Yang PM, Wang JT, Chen PJ, Chan KW, Chu JS, Chen DS. Long-term efficacy of ribavirin plus interferon alfa in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1307-1312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Feld JJ, Hoofnagle JH. Mechanism of action of interferon and ribavirin in treatment of hepatitis C. Nature. 2005;436:967-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 728] [Cited by in RCA: 735] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Werner JM, Serti E, Chepa-Lotrea X, Stoltzfus J, Ahlenstiel G, Noureddin M, Feld JJ, Liang TJ, Rotman Y, Rehermann B. Ribavirin improves the IFN-γ response of natural killer cells to IFN-based therapy of hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2014;60:1160-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Heim MH. 25 years of interferon-based treatment of chronic hepatitis C: an epoch coming to an end. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:535-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Madela K, McGuigan C. Progress in the development of anti-hepatitis C virus nucleoside and nucleotide prodrugs. Future Med Chem. 2012;4:625-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Afdhal N, Zeuzem S, Kwo P, Chojkier M, Gitlin N, Puoti M, Romero-Gomez M, Zarski JP, Agarwal K, Buggisch P. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for untreated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1889-1898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1357] [Cited by in RCA: 1365] [Article Influence: 124.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Afdhal N, Reddy KR, Nelson DR, Lawitz E, Gordon SC, Schiff E, Nahass R, Ghalib R, Gitlin N, Herring R. Ledipasvir and sofosbuvir for previously treated HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1483-1493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1065] [Cited by in RCA: 1064] [Article Influence: 96.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Poordad F, Hezode C, Trinh R, Kowdley KV, Zeuzem S, Agarwal K, Shiffman ML, Wedemeyer H, Berg T, Yoshida EM. ABT-450/r-ombitasvir and dasabuvir with ribavirin for hepatitis C with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1973-1982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 698] [Cited by in RCA: 683] [Article Influence: 62.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hoofnagle JH, Sherker AH. Therapy for hepatitis C--the costs of success. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1552-1553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sarkar S, Lim JK. Advances in interferon-free hepatitis C therapy: 2014 and beyond. Hepatology. 2014;59:1641-1644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Berenguer M. Systematic review of the treatment of established recurrent hepatitis C with pegylated interferon in combination with ribavirin. J Hepatol. 2008;49:274-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Xirouchakis E, Triantos C, Manousou P, Sigalas A, Calvaruso V, Corbani A, Leandro G, Patch D, Burroughs A. Pegylated-interferon and ribavirin in liver transplant candidates and recipients with HCV cirrhosis: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective controlled studies. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:699-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Joshi D, Carey I, Agarwal K. Review article: the treatment of genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C virus infection in liver transplant candidates and recipients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:659-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Fontana RJ, Hughes EA, Bifano M, Appelman H, Dimitrova D, Hindes R, Symonds WT. Sofosbuvir and daclatasvir combination therapy in a liver transplant recipient with severe recurrent cholestatic hepatitis C. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:1601-1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Charlton MR, Gane EJ, Manns MP, Brown RS, Curry MP, Kwo P, Fontana R, Gilroy R, Teperman L, Muir A, McHutchison JG, Symonds WT, Denning J, McNair L, Arterburn S, Terrault N, Samuel D, Forns X. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin for the treatment of established recurrent hepatitis C infection after liver transplantation: preliminary results of a prospective, multicenter study. 2013;. |

| 37. | Highleyman L; AASLD 2013: Sofosbuvir taken before or after liver transplant reduces HCV recurrence. Available from: http: //www.hivandhepatitis.com/hcv-treatment/experimental-hcv-drugs/4400-aasld-2013-sofosbuvir-taken-before-or-after-liver-transplant-reduces-hepatitis-c-recurrence. |