Published online May 25, 2014. doi: 10.5495/wjcid.v4.i2.5

Revised: April 23, 2014

Accepted: May 20, 2014

Published online: May 25, 2014

Processing time: 174 Days and 22.5 Hours

Here we describe the case of a 4-mo-old female who died suddenly without any apparent cause that was initially mistaken as a case of sudden infant death syndrome. Histologic observation of brain sections revealed blue-black bodies in erythrocytes of the blood vessels, suggestive of specific stages of the hematic schizogonic cycle. Further examinations revealed hemozoin and hemosiderin deposits in the parenchyma of all organs, leading to the diagnosis of malaria by Plasmodium falciparum (P. falciparum). The death occurred in Italy, the native country of the infant, two weeks after a Christmas holiday spent in Pakistan, the parents’ birthplace, which has a high malarial endemicity. As this case demonstrates, the diagnosis of malaria should always be considered as a differential diagnosis in subjects, including infants, that die unexpectedly after returning from P. falciparum endemic areas.

Core tip: This report describes the case of a 4-mo-old baby whose sudden death was initially attributed to sudden infant death syndrome. Histologic examination of organ specimens unexpectedly revealed blue-black bodies in erythrocytes, suggestive of specific stages of the hematic schizogonic cycle, and hemozoin and hemosiderin deposits in the parenchyma of all organs. These observations led to the diagnosis of death from malaria by Plasmodium falciparum. In support of this diagnosis, the baby had recently returned from a stay in Pakistan, a region with high malarial endemicity.

- Citation: Pusiol T, Lavezzi AM, Radice F, Alfonsi G, Matturri L. Unsuspected imported malaria in a case of sudden infant death. World J Clin Infect Dis 2014; 4(2): 5-8

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3176/full/v4/i2/5.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5495/wjcid.v4.i2.5

Malaria is an infection caused by the protozoa Plasmodium with high morbidity and mortality in endemic areas, including Asia and Africa[1-3]. The virulence of the malarial agents is a consequence of a number of features, the most important of which is the tendency for parasitized erythrocytes, with the consequent occlusion of the capillaries and blockade of circulation[4,5]. The clinical syndromes associated with Plasmodium infections range from asymptomatic parasitemia to high fever, chills, convulsions, coma and death[6,7]. In infants, in particular, the typical signs of malaria (e.g., febrile illness), are generally absent, and include only sudden behavioral changes like irritability, lethargy, drowsiness[1,6]. Thus, infants are at increased risk for a rapid disease progression due to the undiagnosed infection. In the absence of a timely diagnosis, erythrocyte parasitemia may reach critical values and cause massive hemolysis and multiple organ dysfunction, resulting in death. The World Health Organization estimates that in malaria-endemic areas, infants become vulnerable to Plasmodium at around three months of age, when immunity acquired from the mother starts to wane[2]. Here, we report a case of an unsuspected and postponed malaria diagnosis in a 4-mo-old female, who died suddenly in Italy, her native country, two weeks after a Christmas holiday spent in her parent’s birthplace, Pakistan, which has high malarial endemicity.

The case of a 4-mo-old female who died suddenly during sleep without any apparent cause was sent as a suspected case of sudden infant death syndrome to the “Lino Rossi” Research Center of the Milan University, according to Italian law: 31/2006 “Regulations for Diagnostic Post Mortem Investigation in Victims of the Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) and Unexpected Fetal Death”.

The parents brought their daughter to northern Pakistan, their region of origin, in occasion of the Christmas holiday for around 50 d (from November 20, 2013 to January 10, 2014). During this stay, the baby was in good health. Approximately 15 d before the end of the visit, the parents noticed signs of a mosquito bite on the baby’s face. On the tenth days after their return to Italy, although showing no signs of fever, the baby did not eat and showed a lack of responsiveness. For this reason, the parents brought her directly to the nearest hospital, where she arrived with no signs of heartbeat or breathing. Despite the attempts of resuscitation, physicians confirmed the absence of vital signs and death.

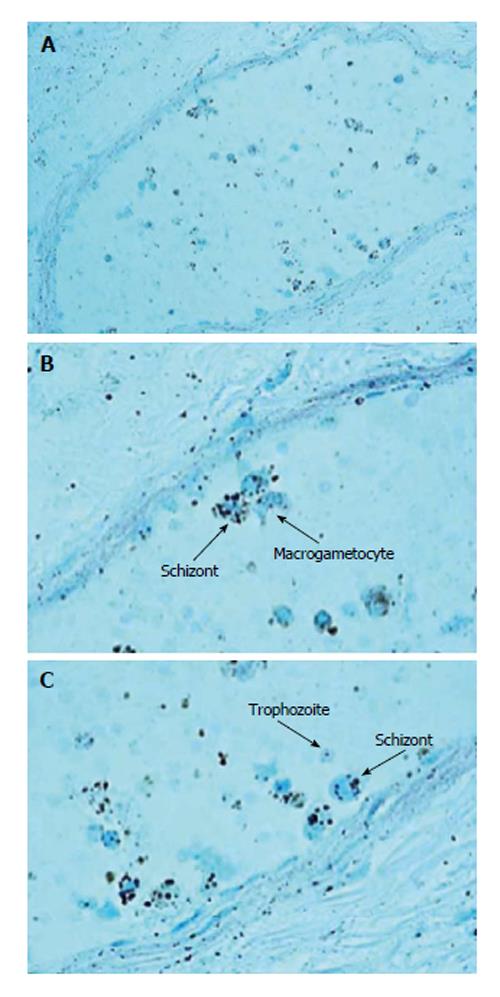

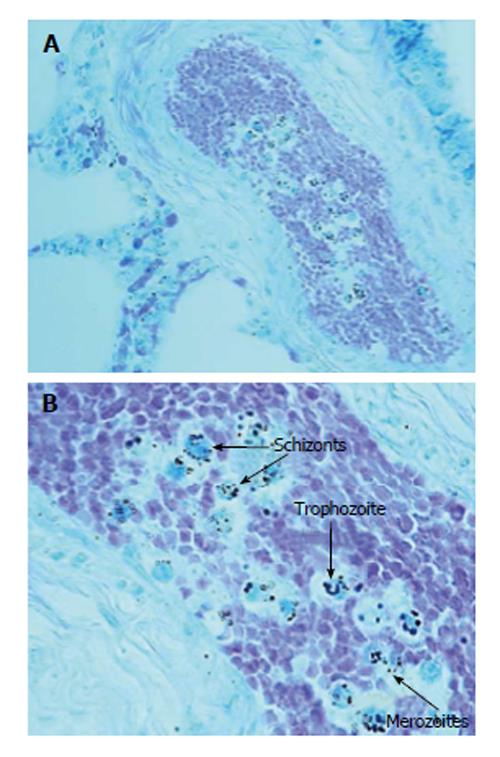

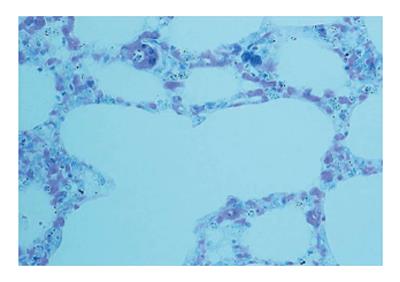

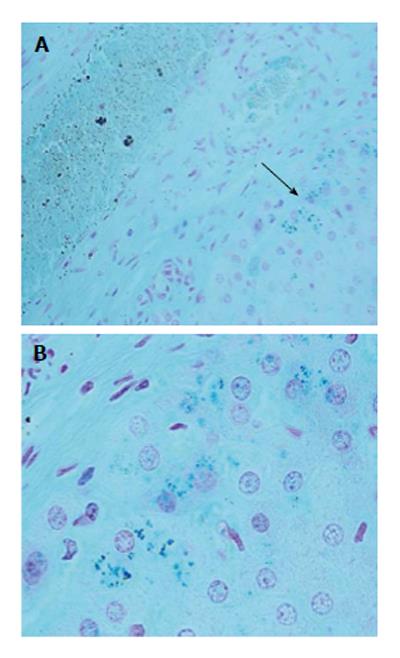

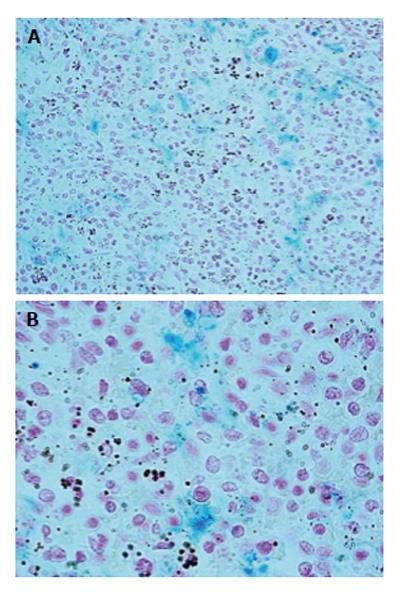

The autopsy examination did not show a clear cause of death, and excluded important disease processes and/or congenital malformations. An in-depth study of the autonomic nervous system, performed according to the above-mentioned Italian law in case of sudden infant death, did not detect any alteration, particularly of the brainstem vital centers. However, examination of hematoxylin/eosin-stained brain sections highlighted the presence of small blue-black bodies within erythrocytes in capillaries, indicative of infection from malarial parasites. The examination was then extended to samples of all organs. Histologic sections were processed with Giemsa staining to determine the intensity and distribution of the parasite in the different stages of the hematic schizogonic cycle in the capillaries of each organ. It was possible to recognize trophozoites, schizonts, merozoites and crescent-shape macrogametocytes, which are a distorted form of gametocyte specific to Plasmodium falciparum that allow differentiation from other types of malarial infection (Figures 1-3). The Perls method for iron was also used to distinguish the intra- and extra-erythrocyte hemozoin and hemosiderin, the malaria pigments arising from rupture of mature schizonts (Figures 4 and 5). Pigmented phagocytic cells were frequently found dispersed in all organs. The final diagnosis was imported acute malignant malaria from Plasmodium falciparum.

Malaria disease begins with the injection of sporozoites from an infected female Anopheles mosquito into the skin of a human host. The sporozoites primarily reach the liver and then develop within the hepatocytes through schizogonic divisions. This leads to the formation of numerous merozoites that, immediately after release in the bloodstream, parasitize red blood cells, thus initiating the intra-erythrocytic cycle, which is responsible for the initiation of clinical malaria[8,9]. Plasmodium parasites therefore have two obligatory intracellular development phases, first in hepatocytes and subsequently in erythrocytes. We believe that in this case, the severe congestion of parasitized erythrocytes observed in microvessels of all organs, and especially in the brain, played a crucial role in the pathogenic mechanism of the sudden death.

The baby returned from a trip in Pakistan, a region where malaria continues to be a serious public health problem. Despite a well-established malaria control program, 500000 malaria infections and 50000 malaria-attributable deaths occur each year in Pakistan[10,11]. Although polymerase chain reaction has been introduced to detect Plasmodium-positive samples, the Giemsa staining method remains, for simplicity and low cost, the gold standard for the diagnosis of Plasmodium infections[12-14]. This report highlights that a diagnosis of malaria must be considered as an important differential diagnosis in subjects who have recently stayed in malarial endemic regions, with or without specific clinical symptoms. Even if the malaria is an infrequently encountered infection in non-endemic areas, particularly in Europe[15], a high degree of suspicion is needed. Furthermore, proper questioning by a doctor is fundamental in the diagnosis of imported malaria, especially when the clinical signs are non-specific and sometimes misleading. This should be applied also in cases of infants who die suddenly in the first months of life, which often occur during sleep and are classified as SIDS.

The paper describes a case of a 4-mo-old female who died suddenly without any apparent cause, which was initially mistaken as a sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) case.

Clinical diagnosis was SIDS and other death cause were not considered.

Acute malignant malaria from Plasmodium falciparum.

Despite the attempts of resuscitation, physicians established the non-resumption of vital signs and death.

SIDS is defined as the sudden death of an infant under one year of age that remains unexplained after a thorough case investigation, including performance of a complete autopsy, examination of the death scene, and a review of the clinical history.

This case with a post-mortem diagnosis of malaria is important from a medicolegal point of view because of the potential responsibility of the physician treating a patient of any age who has returned from endemic areas.

The manuscript is a case report of interest in the area of health, as it can lead to greater awareness among those responsible for the area, to the attention of individuals and newborns who travel from endemic areas in malaria to non-endemic areas.

P- Reviewer: Angel S, Das S, Ferrante A, Oz HS S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: AmEditor E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2011. Geneva: WHO 2011; Available from: http: //www.who.int/malaria/world_malaria_report_2011/en/. |

| 2. | Cibulskis RE, Aregawi M, Williams R, Otten M, Dye C. Worldwide incidence of malaria in 2009: estimates, time trends, and a critique of methods. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Murray CJ, Rosenfeld LC, Lim SS, Andrews KG, Foreman KJ, Haring D, Fullman N, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Lopez AD. Global malaria mortality between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2012;379:413-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1040] [Cited by in RCA: 998] [Article Influence: 76.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ponsford MJ, Medana IM, Prapansilp P, Hien TT, Lee SJ, Dondorp AM, Esiri MM, Day NP, White NJ, Turner GD. Sequestration and microvascular congestion are associated with coma in human cerebral malaria. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:663-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pongponratn E, Riganti M, Punpoowong B, Aikawa M. Microvascular sequestration of parasitized erythrocytes in human falciparum malaria: a pathological study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;44:168-175. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Miller LH, Baruch DI, Marsh K, Doumbo OK. The pathogenic basis of malaria. Nature. 2002;415:673-679. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Harinasuta T, Bunnang D. The clinical features of malaria. Wernsdorfer WH, McGregor I eds. London: Churchill Livingstone 1988; 709-734. |

| 8. | Church LW, Le TP, Bryan JP, Gordon DM, Edelman R, Fries L, Davis JR, Herrington DA, Clyde DF, Shmuklarsky MJ. Clinical manifestations of Plasmodium falciparum malaria experimentally induced by mosquito challenge. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:915-920. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Silamut K, White NJ. Relation of the stage of parasite development in the peripheral blood to prognosis in severe falciparum malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1993;87:436-443. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kakar Q, Khan MA, Bile KM. Malaria control in Pakistan: new tools at hand but challenging epidemiological realities. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16 Suppl:S54-S60. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Khattak AA, Venkatesan M, Nadeem MF, Satti HS, Yaqoob A, Strauss K, Khatoon L, Malik SA, Plowe CV. Prevalence and distribution of human Plasmodium infection in Pakistan. Malar J. 2013;12:297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mahajan B, Zheng H, Pham PT, Sedegah MY, Majam VF, Akolkar N, Rios M, Ankrah I, Madjitey P, Amoah G. Polymerase chain reaction-based tests for pan-species and species-specific detection of human Plasmodium parasites. Transfusion. 2012;52:1949-1956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | van Hellemond JJ, Rutten M, Koelewijn R, Zeeman AM, Verweij JJ, Wismans PJ, Kocken CH, van Genderen PJ. Human Plasmodium knowlesi infection detected by rapid diagnostic tests for malaria. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1478-1480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Petithory JC, Ardoin F, Ash LR. Rapid and inexpensive method of diluting Giemsa stain for diagnosis of malaria and other infestations by blood parasites. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:528. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Odolini S, Parola P, Gkrania-Klotsas E, Caumes E, Schlagenhauf P, López-Vélez R, Burchard GD, Santos-O’Connor F, Weld L, von Sonnenburg F. Travel-related imported infections in Europe, EuroTravNet 2009. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:468-474. [PubMed] |