Published online Feb 25, 2014. doi: 10.5495/wjcid.v4.i1.1

Revised: December 21, 2013

Accepted: February 3, 2014

Published online: February 25, 2014

Processing time: 160 Days and 2 Hours

With the emergence of novel etiologic organisms, pan-resistance, and invasive medical care infective endocarditis continues to be evasive, requiring newer approaches and modified treatment guidelines. Presented here is the case of a 75-year-old male with history of systolic heart failure with an automatic internal cardioverter defibrillator (AICD) implantation and a prosthetic mitral valve who presented with generalized malaise and progressive shortness of breath for 6 d. He was found to have positive blood cultures for gram positive rod shaped bacteria identified as Corynebacterium straitum, but was not considered as the etiological pathogen initially as it a usual skin contaminant. Later this bacterium was found to be the causative agent for the patient’s endocarditis. This case highlights the importance of identifying the role of this uncommon commensal in invasive disease. With the use of effective antibiotic regimen and awareness of these new pathogens in invasive disease, mortality and morbidity can be prevented with initiation of early appropriate therapy.

Core tip: This report highlights the pathogenicity of previously considered commensals like Corynebacterium striatum in severe human disease. Clinicians and microbiologists should not overlook the potential virulence of commensals in appropriate clinical situations. Furthermore, our case highlights an important point regarding the emergence of new pathogens in the etiology of infective endocarditis and also throws light on the increased incidence of endocarditis with the use of indwelling catheters and aggressive invasive medical management. As this issue is of growing concern with respect to infections that are easily avoidable.

- Citation: Agarwal V, Parikh V, Lakhani M, De C, Motivala A, Mobarakai N. Sub-acute endocarditis by Corynebacterium straitum: An often ignored pathogen. World J Clin Infect Dis 2014; 4(1): 1-4

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3176/full/v4/i1/1.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5495/wjcid.v4.i1.1

The epidemiological profile of infective endocarditis has changed drastically over the last several years with an estimated 10000 to 15000 new cases of IE diagnosed each year in United States. The number of cases of hospital acquired endocarditis has been on a rise with an estimated 7.5% to 29% of total cases of endocarditis in tertiary-care centre[1]. Intravenous indwelling catheters being one of the important causes of amplified risk of bacteremia. Corynebacerium straitum (CS) previously considered a saprophyte on skin and mucosa is now emerging as a causative organism for various infections, not only in immunocompromised but in immunocompetent individuals as well. Positive blood cultures for CS should not be neglected. The exact infectious potential of these bacteria and their judicious antimicrobial treatment is a challenging but necessary task.

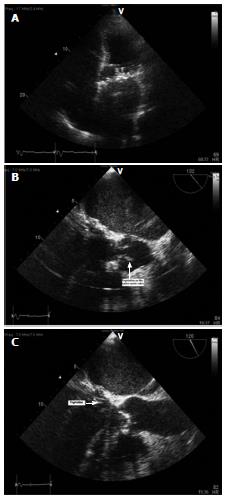

A 75-year-old male with history of systolic heart failure with an automatic internal cardioverter defibrillator implantation and a prosthetic mitral valve presented with generalized malaise and progressive shortness of breath for 6 d. Patient also noticed worsening of lower extremity edema. He denied chest pain, fever, cough and palpitations. Physical exam revealed a new systolic murmur, bilateral crackles and positive pitting pedal edema. Based on initial assessment a diagnosis of acute decompensated heart failure secondary to suspected prosthetic valve infective endocarditis was made. Over the next 48 h four sets of blood cultures were drawn. Transthoracic echocardiography showed dilated left atrium and possible mitral valve vegetation (Figure 1A). In addition to the symptomatic treatment of heart failure, daptomycin, gentamicin, ceftriaxone and rifampin were started empirically. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) revealed a subcentimeter vegetation on the aortic valve (Figure 1B) in addition to small, protruding, echogenic, mobile vegetation at the prosthetic mitral valve annulus (Figure 1C). Four sets of blood cultures drawn 24 h apart, all grew CS. Initially, was thought to be a contaminant but later confirmed as a pathogen with gram stain and microbiological characterization which included acid fast staining, chemical and antibiotic testing. Antimicrobial susceptibility of the above organism by clinical and laboratory standards institute showed sensitivity of the organism to vancomycin, ampicillin (intermediate sensitivity), daptomycin, rifampin and gentamicin. Based on antibiotic sensitivity, daptomycin was discontinued and ampicillin was added. Ceftriaxone was continued initially as the patient also has a urinary ttract infection but was later discontinued after second set of cultures showed the same results and urine cultures were negative. No other bacteria were isolated from the blood cultures. Subsequent blood cultures drawn 4 d later were negative. Patient’s condition improved over a period of 3 wk. Antibiotics were continued for a total of 6 wk.

One month prior to this admission, patient was admitted to a tertiary care center for diverticular bleed, which was treated with IV resuscitation via an internal jugular venous access. This was the presumed source of infection.

Nondiphtherial corynebacteria also known as coryneforms, are a widely diverse collection of bacteria that are grouped together on basis of their 16S rDNA[2]. The diversity of the group is further exemplified by the wide range of guanine-plus-cytosine content of the nucleotides. Although frequently considered as colonizers or contaminants they have been associated with invasive disease, particularly in immunocompromised patients. These organisms have been specifically implicated in bacteremia associated with catheterizations, shunts, pacemakers causing meningitis, osteomyelitis, prosthetic heart valve endocarditis and peritonitis, often seen in patients undergoing dialysis or have associated empyema, pneumonia and skin infections[3,4]. Patients infected with nondiphtherial organisms usually have significant medical co-morbidity or immunosuppression.

CS is one of the less known nondiphtherial species belonging to the genus corynebacteria. Frequently distinguished from other coryneform bacteria by being non acid fast, nitrate reducing, utilizing glucose and sucrose and having colonies that are white grey or yellowish green in color. This species is non-motile. Microscopically they are larger when compared to the other coryneform bacteria and on gram stain have a typical striated appearance. Therefore named Corynebacterium striatum. CS is found in the anterior nares and on the skin, face and upper torso of normal individuals. There is a growing concern for its role as a pathogen in various disease entities, as noted in few case studies[5-7].

There has been a steep rise in the number of reported cases of health care acquired infective endocarditis over the last decade. This is most likely due to the vast use of invasive procedures in people with or without pre-existing valvular disease[8]. Effective antibiotic regimen has managed to curb the traditional etiological organisms, but there is growing concern for identification of newer unrecognized pathogens. CS generally considered a commensal, has now been implicated as a causative organism in various infections. Although nontoxigenic, this organism has been associated with invasive infections in patients with implanted cardiac device and prosthetic valves[9], usually in an immunocompromised setting. There have been reports of CS bacteremia attributed to indwelling venous catheters[10]. CS infection along with C. jeikeium has been shown to be associated with nosocomial risk factors in some studies[11]. Most of the reported CS isolates have been susceptible to a wide spectrum of antibiotics. There have been few reported cases of multi drug resistant CS[12]. In general they are resistant to penicillin’s but have been reported to be susceptible to B-lactams and vancomycin. There are no established guidelines for the management of corynebacteria yet. But in the light of impending multidrug resistance and nosocomial infections, there is need for appropriate guidelines to be established. Positive blood cultures for Corynebacterium striatum should not be neglected as a contaminant because of lack of data involving its role as a pathogen, especially in a hospital environment. Recognition and classification of diphtherial organisms continues to be a challenge for various laboratories as there is discrepancy in diagnosis of contamination in opposition to causative pathogen[13]. Delay in treatment increases morbidity and mortality.

This report highlights the pathogenicity of previously considered commensals like Corynebacterium striatum in severe human disease. Clinicians and microbiologists should not overlook the potential virulence of commensals in appropriate clinical situations.

Acute decompensated heart failure with fluid overload. Found to be febrile with positive blood cultures.

Sub-acute endocarditis due to Corynebacerium straitum (CS).

Most Coryneform bacteria are commensals on human skin and are ubiquitous in our environment. Initially positive blood cultures for this organism was thought to be a contaminant, but was later found to be the etiological agent of endocarditis.

Organisms isolated from blood culture underwent staining with Gram’s method and acid fast staining. Microbiological characterization was also performed.

Presence of vegetation was identified using transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography.

Sub-acute endocarditis due to invasive CS infection.

Antibiotic therapy with Rifampin, ampicillin, and gentamycin. There is lack of data with regards to treatment of endocarditis due to CS.

Cardioverter defibrillator: An implantable cardioverter defibrillator is a small device that's placed in the chest or abdomen. Used to treat arrhythmias; Vegetation: Endocarditis is characterized by a prototypic lesion, the vegetation, which is a mass of platelets, fibrin, microcolonies of microorganisms, and scant inflammatory cells.

Clinicians and microbiologists should not overlook the potential virulence of commensals like CS in appropriate clinical situations.

This is just a single case report describing a human endocarditis caused by CS. The case report is interesting and the manuscript is well written.

P- Reviewers: Morita YS, Soriano F S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Fernández-Guerrero ML, Verdejo C, Azofra J, de Górgolas M. Hospital-acquired infectious endocarditis not associated with cardiac surgery: an emerging problem. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:16-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Woese CR. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:221-271. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Lee PP, Ferguson DA, Sarubbi FA. Corynebacterium striatum: an underappreciated community and nosocomial pathogen. J Infect. 2005;50:338-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Oliva A, Belvisi V, Iannetta M, Andreoni C, Mascellino MT, Lichtner M, Vullo V, Mastroianni CM. Pacemaker lead endocarditis due to multidrug-resistant Corynebacterium striatum detected with sonication of the device. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4669-4671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Díez-Aguilar M, Ruiz-Garbajosa P, Fernández-Olmos A, Guisado P, Del Campo R, Quereda C, Cantón R, Meseguer MA. Non-diphtheriae Corynebacterium species: an emerging respiratory pathogen. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32:769-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cazanave C, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Hanssen AD, Patel R. Corynebacterium prosthetic joint infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:1518-1523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wong KY, Chan YC, Wong CY. Corynebacterium striatum as an emerging pathogen. J Hosp Infect. 2010;76:371-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Martín-Dávila P, Fortún J, Navas E, Cobo J, Jiménez-Mena M, Moya JL, Moreno S. Nosocomial endocarditis in a tertiary hospital: an increasing trend in native valve cases. Chest. 2005;128:772-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Abi R, Ez-Zahraouii K, Ghazouani M, Zohoun A, Kheyi J, Chaib A, Elouennass M. A Corynebacterium striatum endocarditis on a carrier of pacemaker. Ann Biol Clin (Paris). 2012;70:329-331. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Chen FL, Hsueh PR, Teng SO, Ou TY, Lee WS. Corynebacterium striatum bacteremia associated with central venous catheter infection. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2012;45:255-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Belmares J, Detterline S, Pak JB, Parada JP. Corynebacterium endocarditis species-specific risk factors and outcomes. BMC Infect Dis. 2007;7:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fernández Guerrero ML, Molins A, Rey M, Romero J, Gadea I. Multidrug-resistant Corynebacterium striatum endocarditis successfully treated with daptomycin. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;40:373-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Neal SE, Efstratiou A. International external quality assurance for laboratory diagnosis of diphtheria. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:4037-4042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |