Published online Oct 23, 2012. doi: 10.5494/wjh.v2.i5.45

Revised: July 12, 2012

Accepted: July 23, 2012

Published online: October 23, 2012

The National Institute for Clinical Excellence in the United Kingdom published a new set of guidelines on the management of primary hypertension in August 2011, reflecting some important changes in the diagnosis and treatment of hypertension. Ambulatory blood pressure measurement is now the new gold standard for diagnosis. Home blood pressure monitoring is a useful alternative for the diagnosis and monitoring of hypertension. Calcium channel blockers (CCB) and blockers of the renin-angiotensin system have surpassed diuretics and β-blockers as first line options. Patients younger than 55 should receive an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, or an angiotensin receptor blocker if the former is not tolerated. Older patients should be started on a CCB. A thiazide diuretic can be added to these two groups for better blood pressure control, but. chorthalidone and indapamide are the preferred diuretics as they showed favorable outcomes in large clinical trials. Treatment with these three drug classes should be sufficient in the majority of patients, but if triple therapy is still insufficient, referral to a hypertension specialist is recommended. Additional diuretic therapy, spironolactone, or an α or β blocker can be used as the fourth line treatment.

- Citation: Cheung BMY, Cheung TT. Nice new hypertension guidelines. World J Hypertens 2012; 2(5): 45-49

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3168/full/v2/i5/45.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5494/wjh.v2.i5.45

Hypertension is exceedingly common worldwide. Its prevalence is about 30% in US and about 20% in China[1]. There are around one billion people with hypertension in the world today. Treatment to lower blood pressure has been shown to reduce the risk of stroke and myocardial infarction, and reduce the incidence of heart failure and the progression of chronic kidney disease.

The key to reducing cardiovascular disease is the measurement of the blood pressure of all members of the population, the detection of everyone with hypertension whose blood pressures fall within the criteria for treatment, and the availability of good treatment leading to good blood pressure control. Measures such as cutting sodium intake, eating more fruits and vegetables, fewer calories and more regular exercise[2] would shift the average blood pressure across the whole population, which would in turn reduce the number of people with hypertension and the number of cardiovascular events. This is the population or public health approach that requires government action.

At the other end of the scale, better care of individual patients with hypertension also brings dividends. It is in this spirit that guidelines on the management of hypertension are developed. In 2011, American and British guidelines on the management of hypertension were scheduled to be updated. The British guidelines, developed by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), were published in August 2011[3].

What is special about the NICE methodology is that it is highly evidence based and incorporates cost-effectiveness considerations in its guidance. Compared to many other consensus guidelines, it is less dependent on expert opinions, but is keen to include a diverse range of opinions, including non-specialists, non-clinicians, and the pharmaceutical industry. These stakeholders were engaged in the guideline development process.

The 2011 NICE guidelines are intentionally limited in scope. While they cover the huge majority of hypertensive patients, special groups such as secondary hypertension, diabetic, pregnant or paediatric patients are not covered.

There are several significant changes in these guidelines. Essentially, the guidelines break new ground in the method of diagnosis of hypertension, the initiation and monitoring of drug treatment, and the choice of antihypertensive drug treatment.

Ines break new ground in the method of diagnosis of hypertension, the initiation and monitoring of drug treatment, and the choice of antihypertensive drug treatment.

Agnosis of hypertension, the initiation and monitoring of drug treatment, and the choice of antihypertensive drug treatment.

Nd monitoring of drug treatment, and the choice of antihypertensive drug treatment.

Choice of antihypertensive drug treatment.

Ambulatory blood pressure is now the new gold standard in the diagnosis of hypertension. If the clinic blood pressure is 140/90 mmHg or higher, it is recommended to offer patients ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to confirm the diagnosis. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is valuable not only in people with white coat hypertension, but also in people whose ambulatory blood pressures are higher than blood pressure readings in the clinic. This entity is called reverse white coat hypertension or masked hypertension[4]. Clinic blood pressure underestimates the true blood pressure in these individuals, and therefore traditional blood pressure measurements result in under-treatment, dangerous masked hypertension with a poor prognosis. The existence and the prognosis of this entity provide the rationale for the recommendation of ambulatory or home blood pressure monitoring in the new guidelines.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring also allows blood pressure to be monitored during sleep, and is useful to determine nocturnal dipping in patients with hypertension. A night time fall is normal but an absence of nocturnal dipping is associated with poorer health outcomes and end organ damage. Therefore, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring helps to identify this group of patients who are at higher risk.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is not always available and its repeated use for monitoring purposes is inconvenient as blood pressure is measured twice every hour during the usual waking hours of the individual. During the night, hourly measurement can disturb the normal bio-rhythm and induce a state of alarm. This can disturb the normal nocturnal dip in blood pressure and overestimate the nocturnal blood pressure. Moreover, recording for 24 h sometimes fails because of machine error, displacement of the cuff or its removal by the patient. In patients with atrial fibrillation, automated blood pressure readings are made on individual beats, and so these may not truly reflect the mean level of blood pressure.

Home blood pressure monitoring is now also recognised as being useful and informative in the diagnosis of hypertension and the monitoring of blood pressure[5]. Patients are recommended to record the blood pressure twice daily, each recording with two consecutive measurements, for at least 4 d. Home blood pressure monitors are now inexpensive and many patients can afford to buy one or receive one as a gift. Therefore, it encourages patients to be involved in their own care and they can provide a large number of readings spread over a long period of time. The drawbacks are that they are not as easily validated as the machines in the clinic, and that their accuracy depends on adequate resting before measurement, proper application of cuff and correct operation of the machine. Significant measurement errors may occur in patients with arrhythmias. There is also a danger that patients may adjust their medications, increase or decrease them depending on the home blood pressure readings, a practice which should be discouraged in most cases.

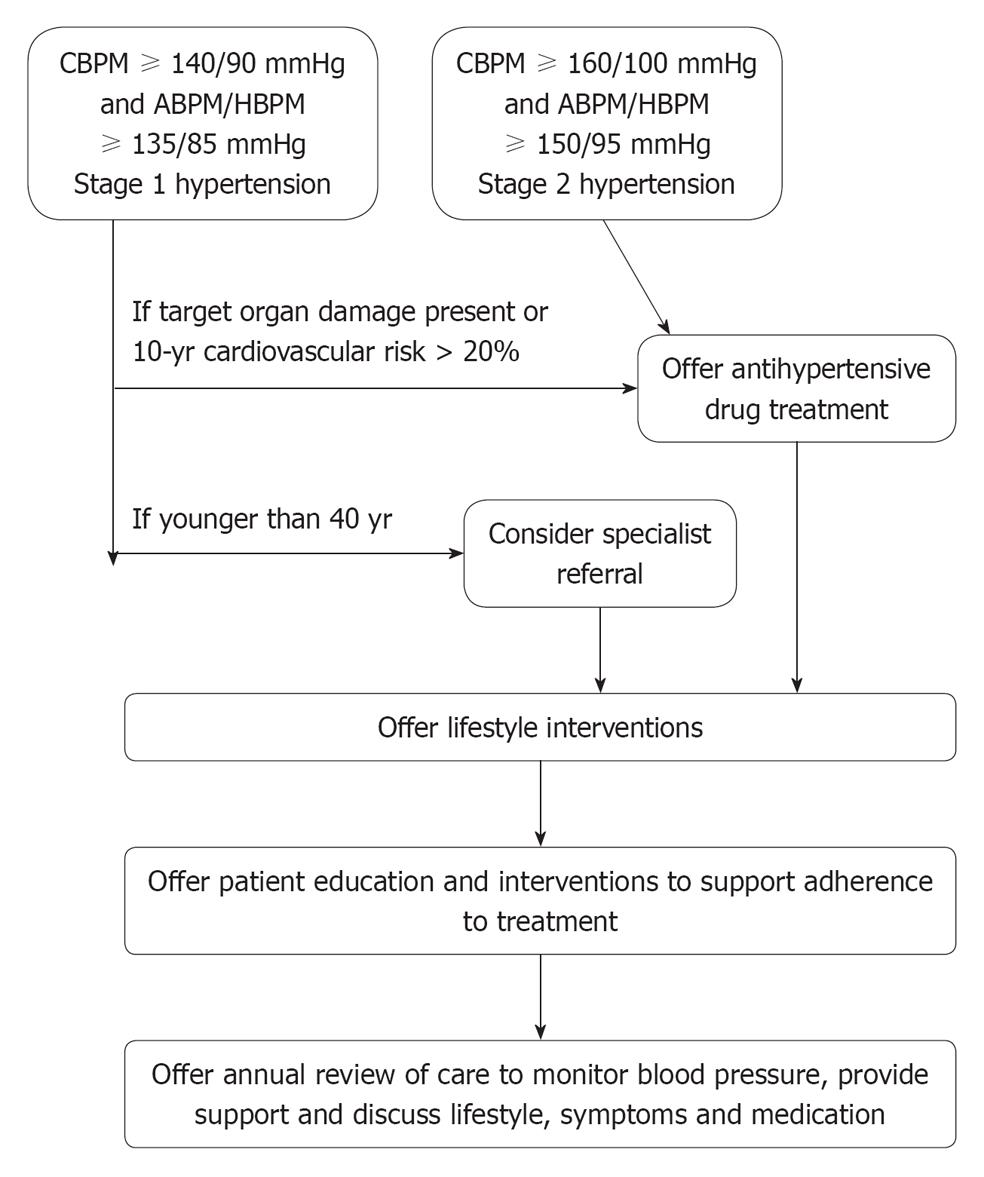

The 2011 NICE guidelines recognise that prompt control of blood pressure is needed in patients who present with more severe hypertension, e.g., stage 2 hypertension (clinic blood pressure ≥ 160/100 mmHg or ambulatory/home blood pressure ≥ 150/95 mmHg) (Table 1). In these patients, initiation of drug treatment should be considered because lifestyle changes alone are unlikely to be enough to achieve satisfactory blood pressure control, or achieve that sufficiently quickly (Figure 1). Patients with stage 1 hypertension but with evidence of target organ damage (e.g., left ventricular hypertrophy, albuminuria, hypertensive retinopathy), established cardiovascular disease, renal disease, diabetes or those whose 10-year cardiovascular risk (assessed by a suitable risk scoring system[6]) exceeds 20% should also receive drug treatment early.

| Stage 1 hypertension |

| Clinic BP is 140/90 mmHg or higher and |

| ABPM or HBPM average is 135/85 mmHg or higher |

| Stage 2 hypertension |

| Clinic BP 160/100 mmHg is or higher and |

| ABPM or HBPM daytime average is 150/95 mmHg or higher |

| Severe hypertension |

| Clinic BP is 180 mmHg or higher or |

| Clinic diastolic BP is 110 mmHg or higher |

Patients under the age of 40 have a higher chance of secondary hypertension and so should be considered for specialist referral for investigation and treatment of these causes of hypertension.

Clinic blood pressure measurements should be used to monitor the response to treatment. The target blood pressure is defined as lower than 140/90 mmHg for those younger than 80 years old. If the “white coat effect” is present, home blood pressure monitoring can be used with the target average blood pressure of 135/85 mmHg. The new guidelines set a less stringent clinic blood pressure target for people aged 80 and over -150/90 mmHg. This is based on the HYpertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) that recruited patients aged 80 and above, and used this target blood pressure[7]. These patients usually have a wide pulse pressure because of the high systolic pressure resulting from atherosclerosis. If the systolic blood pressure is brought below 140 mmHg, the diastolic blood pressure can be considerably lower than 90 mmHg. Moreover, patients may have to take multiple drugs, which could lead to considerable side effects. The new guidelines also set target blood pressures for ambulatory and home blood pressure monitoring, i.e., below 135/85 mmHg in people aged under 80, and below 145/85 mmHg in people aged 80 and over.

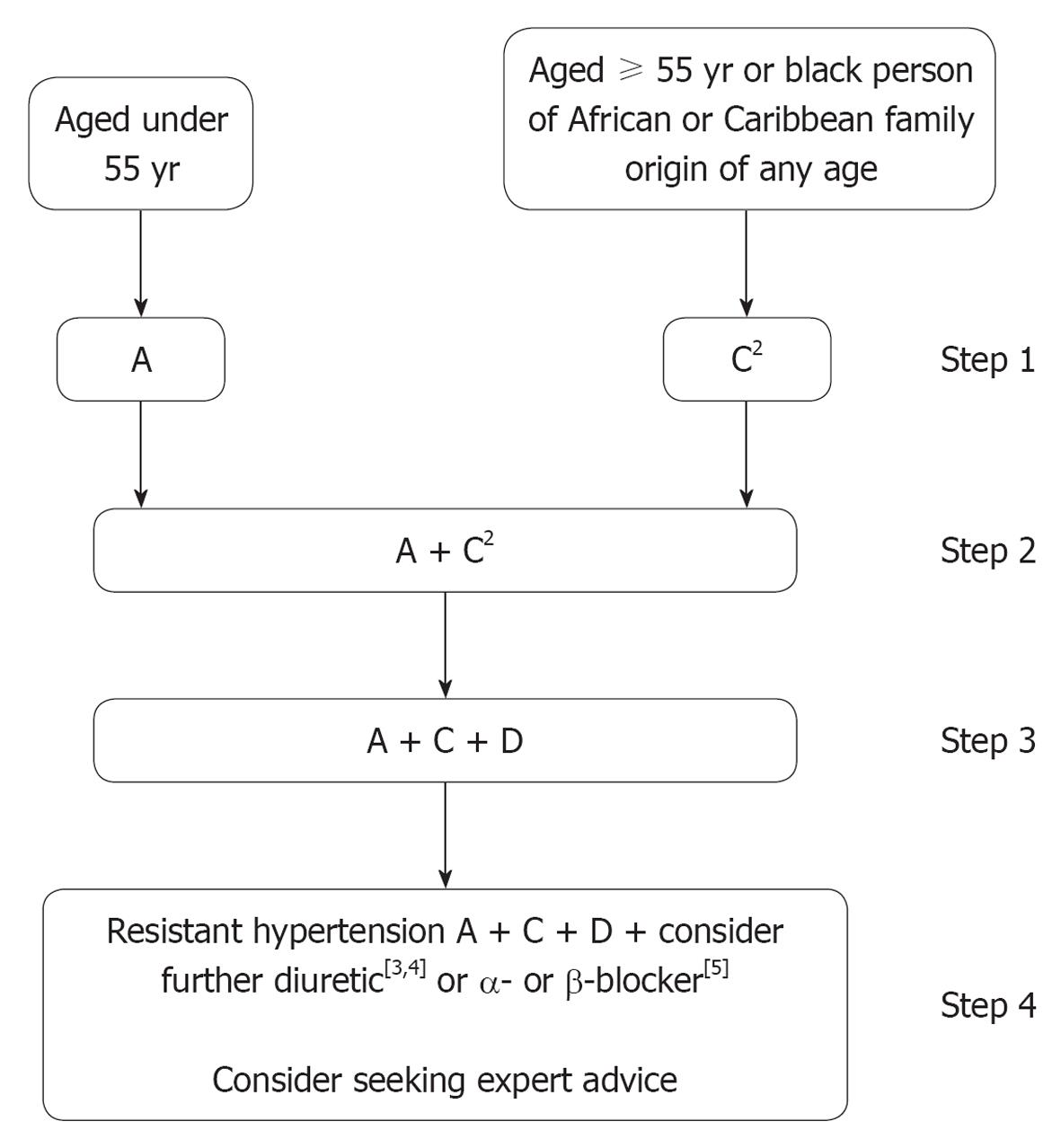

In the new guidelines, there are changes to the recommended first line treatment. As before, it is recommended that patients under the age of 55 initially receive an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or a “low-cost” angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) (Figure 2). Combination of an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor and an ARB is not recommended for the treatment of hypertension. For patients over the age of 55, and for patients of any age of African or Caribbean family origin, a calcium channel blocker (CCB) is the first drug to be used. Diuretics are now a second line agent and will be an alternative for patients who cannot tolerate CCB.

CCB and blockers of the renin-angiotensin system have surpassed diuretics and β-blockers as first line drugs largely as a result of the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial (ASCOT) study, which showed that these newer agents were better than older agents in terms of cardiovascular outcome[8]. Moreover, in ASCOT and in meta-analysis[9], ARB and ACEI were associated with a decrease in new onset diabetes whereas diuretics and β-blockers were associated with an increase in risk for the condition.

Interestingly, chorthalidone and indapamide are the recommended thiazide diuretics as they showed favourable outcomes in large clinical trials, such as the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT)[10] and HYVET[7]. In the UK, hydrochlorothiazide and bendrofluazide have been frequently prescribed for the treatment of hypertension. The former is often added to an ACEI or an ARB in fixed dose combination tablets.

Treatment with these three drug classes should be sufficient in the majority of patients, but if triple therapy is insufficient, referral to a hypertension specialist is recommended. α and β adrenergic antagonists do not even make fourth place among recommendations; this is taken by spironolactone. Although spironolactone has been found in recent years to be a useful drug for resistant hypertension[11], it may increase the risk of hyperkalaemia. In those high risk patients, higher dose of a thiazide diuretic should be considered. Unlike spironolactone, the newer aldosterone antagonist eplerenone does not cause gynaecomastia. Whether it may be used in place of spironolactone for the treatment of hypertension is unclear. α-blockers were found wanting in ALLHAT, in which treatment with an α-blocker was associated with more heart failure. β-blockers were already relegated to fourth line treatment in the previous NICE guidelines, because they control blood pressure poorly in the elderly and tend to cause type 2 diabetes.

The new UK guidelines, based on the best available current evidence, may be criticised for the heavy reliance on large scale randomised controlled trials. As a result, newer drugs are favoured while older drugs may be disadvantaged. Similarly, lifestyle and population measures have not been given their due recognition because of the lack of randomised controlled trials showing improvements in hard cardiovascular outcomes.

At first sight, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring seems to be expensive and time-consuming. At least, practices and clinics would have to purchase more of these machines, which cost thousands of pounds. However, a cost-effectiveness analysis undertaken by NICE showed that the use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to confirm the diagnosis of hypertension saves costs in the long run for the National Health Service[12].

The relationship between blood pressure and cardiovascular risk is continuous. Therefore, the blood pressure levels chosen for the diagnosis of hypertension and target blood pressures are arbitrary. Treatment decisions should not be based on blood pressure levels alone, however accurately they can be determined, but should also include an assessment of risks and benefits.

Hypertension is prevalent worldwide and aging of the population means that there are more and more people with hypertension. Therefore, the scale of the problem of diagnosing, treating and controlling hypertension is immense. Current efforts are channelled towards the detection and treatment of hypertension in middle and old age. The linear rise in the prevalence of hypertension with age means that measures to prevent hypertension, such as a healthy diet and regular physical activity, should start early in life. For those who have already developed hypertension, early diagnosis and treatment is important. Existing antihypertensive drugs are not ideal individually and so a combination of drugs is needed in a large proportion of patients. The choice of such drugs should be rational and evidence-based.

Peer reviewer: Gianni Losano, Professor, Division of Physiology, University of Turin, Corso Raffaello, 30, 10125 Turin, Italy

S- Editor Xiong L L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Cheung BMY, Ong KL. The Challenge of Managing Hypertension. Public Health in the 21st Century. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger Publishing 2010; . |

| 2. | Cheung BMY, Lam TC. Hypertension and diet. Encyclopaedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition. London: Academic Press 2003; 3194-3199. |

| 3. | National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Hypertension: Clinical management of primary hypertension in adults. Available from: http://egap.evidence.nhs.uk/CG127. Accessed September 21, 2011. |

| 4. | Mancia G, Bombelli M, Seravalle G, Grassi G. Diagnosis and management of patients with white-coat and masked hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:686-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hodgkinson J, Mant J, Martin U, Guo B, Hobbs FD, Deeks JJ, Heneghan C, Roberts N, McManus RJ. Relative effectiveness of clinic and home blood pressure monitoring compared with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in diagnosis of hypertension: systematic review. BMJ. 2011;342:d3621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Conroy RM, Pyörälä K, Fitzgerald AP, Sans S, Menotti A, De Backer G, De Bacquer D, Ducimetière P, Jousilahti P, Keil U. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:987-1003. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, Staessen JA, Liu L, Dumitrascu D, Stoyanovsky V, Antikainen RL, Nikitin Y, Anderson C. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1887-1898. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Dahlöf B, Sever PS, Poulter NR, Wedel H, Beevers DG, Caulfield M, Collins R, Kjeldsen SE, Kristinsson A, McInnes GT. Prevention of cardiovascular events with an antihypertensive regimen of amlodipine adding perindopril as required versus atenolol adding bendroflumethiazide as required, in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:895-906. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Elliott WJ, Meyer PM. Incident diabetes in clinical trials of antihypertensive drugs: a network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;369:201-207. [PubMed] |

| 10. | ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288:2981-2997. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Václavík J, Sedlák R, Plachy M, Navrátil K, Plásek J, Jarkovsky J, Václavík T, Husár R, Kociánová E, Táborsky M. Addition of spironolactone in patients with resistant arterial hypertension (ASPIRANT): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Hypertension. 2011;57:1069-1075. [PubMed] |