Published online Jun 28, 2012. doi: 10.5412/wjsp.v2.i3.16

Revised: January 6, 2012

Accepted: February 15, 2012

Published online: June 28, 2012

AIM: To describe our method of transcylindrical cholecystectomy (TC) and its potential advantages over other surgical approaches for treating symptomatic gallstones.

METHODS: TC is a modified minilaparotomy performed gas-free through a single cylinder 3.8 cm (or occasionally 5.0 cm) in diameter and 10.0 cm in length. An efficacy, prospective and longitudinal study was conducted. Experience was accumulated over 15 years (1993-2008) and 387 operations, showing the feasibility and safety of TC. Since 2008, we have performed TC under local anesthesia plus sedation in most cases of symptomatic cholelithiasis.

RESULTS: Between 1993 and 2008, TC was carried out in 364 consecutive patients, including 78 acute cholecystitis, 37 acute biliary pancreatitis and 48 suspected choledocholithiasis. In another 23 patients (5.9%), the operation was converted into a subcostal laparotomy. Ten postoperative complications (2.75%) were registered in this series: 5 wound infections, 2 bile leaks (one causing death), 2 hemorrhages (requiring reoperation) and 1 residual stones. Since 2008, TC was planned and started under local anesthesia plus sedation in 60 patients. In another 12 patients (16.7%), the operation was decided, started and completed under general anesthesia. Surgery was satisfactorily completed through the cylinder in all patients of this series. In 13 patients (out of 60; 21.7%), local anesthesia was converted to general anesthesia. Among patients whose operation was attempted under local anesthesia (n = 60), postoperative complications were: 1 wound infection (1.7%), 2 wound seromas (3.3%) and 3 nauseas (5%). All but two patients in this series were discharged from hospital on the day of surgery and all patients were satisfied with the procedure. In our experience using TC, we have not had any cases of main bile duct injury.

CONCLUSION: TC should be considered in the search for the best alternative in the management of gallstone disease, deserving its inclusion in prospective randomized trials.

- Citation: Grau-Talens EJ, Giner M. Technique of transcylindrical gas-free cholecystectomy. World J Surg Proced 2012; 2(3): 16-20

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2832/full/v2/i3/16.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5412/wjsp.v2.i3.16

Cholecystectomy is generally accepted as the treatment of choice for symptomatic gallstone disease and is one of the most frequently performed surgical procedures in the world. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is currently the gold standard for removal of the gallbladder. Laparoscopic vs minilaparotomy cholecystectomy shows no differences in mortality, complications and recovery. However, minilaparotomy compares favorably in operative time[1]. Despite the lack of evidence of superiority over a minilaparotomy, the laparoscopic procedure is currently still the method of choice.

Laparoscopic surgery (LC) promptly offered alternatives for the treatment of complications associated with cholelithiasis, such as cholecystitis and choledocholithiasis, for which technical requirements and skills are much more demanding than those required for simple cholecystectomy. After some experience with LC, an increasing number of cholecystitis cases can be solved by a laparoscopic approach. However, expertise is not always available, particularly in the emergency setting. In these cases, the rates of conversion to open surgery are high. Similarly, bile duct exploration and the treatment of bile duct calculi are feasible laparoscopically. However, the practicality of this method is reserved for a few surgeons, with operating times reported to be two to three times longer than with our method[2].

We developed a gas-free transcylindrical cholecystectomy (TC) technique[3], which is somewhere between minilaparotomy cholecystectomy and laparoscopic cholecystectomy, is practiced gas-free and basically involves removal of the gallbladder through a unique cylindrical retractor. TC has been shown to be applicable, safe and efficient in treating cholelithiasis, cholecystitis and cholecholithiasis[4]. Currently we use TC under local anesthesia in most patients[5].

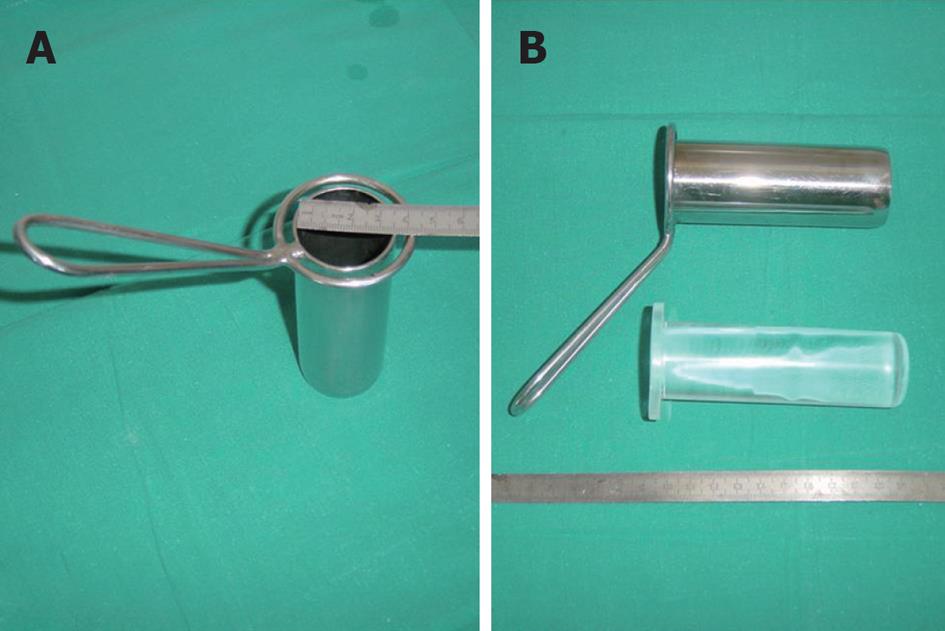

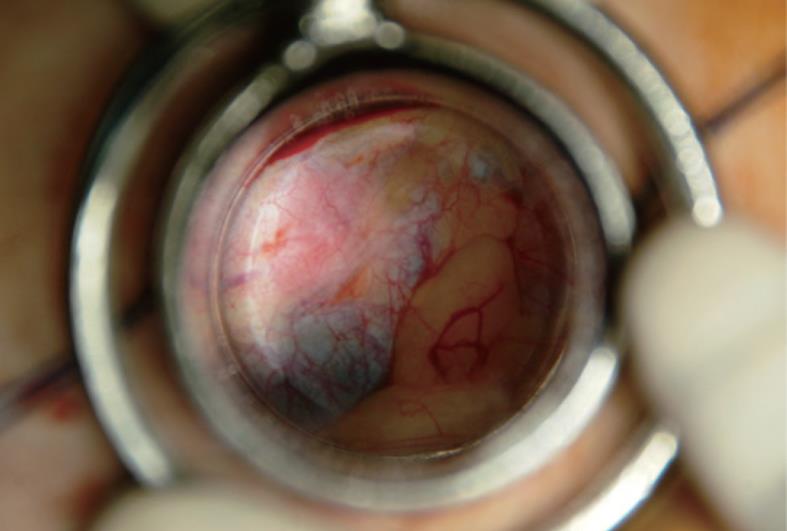

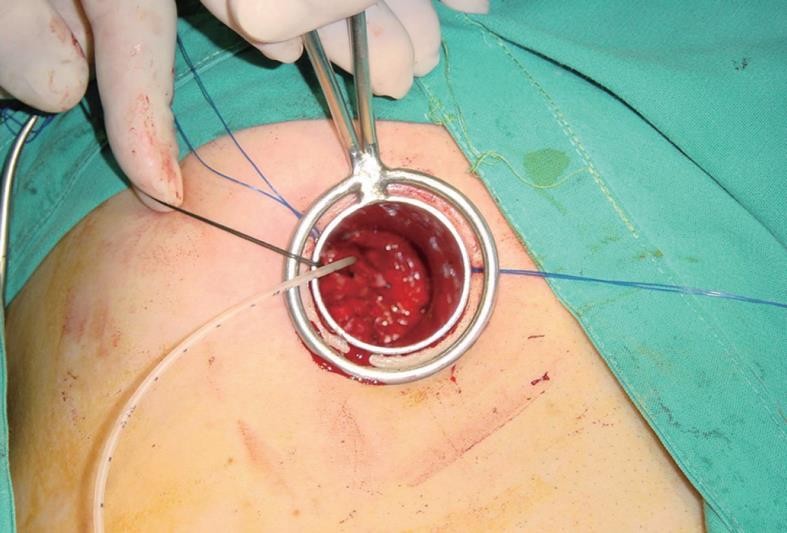

A cylinder, artisanally made, 10.0 cm long and 3.8 cm in diameter, is used with a transparent metacrilate plunger that, once introduced into the abdomen through an epigastric transverse incision, with dissection of the anterior rectus muscle fibers, allows visualization of the surgical field before unplugging (Figures 1-3). The skin incision uniformly measures 4.5 cm in length. Occasionally, a 5 cm cylinder is used through an incision that measures 7.5 cm. The 5 cm cylinder is used in case of known acute cholecystitis or when difficulties are anticipated or encountered at operation through the smaller cylinder. The cylinder commonly used is made of stainless steel. Occasionally, a cylinder totally made of metacrilate is used to facilitate intraoperative cholangiography.

Before reaching a working position, the cylinder is gently moved. The blunt shape of the plunger end facilitates this movement. The plunger can be withdrawn and reintroduced as many times as necessary to identify anatomic structures. Withdrawing the plunger does not cause any suction because it is slightly narrower than the lumen of the cylinder. Once the plunger is withdrawn, adhesions are easily freed. The binocular vision and the straightforward possibility of introducing materials through the cylinder (gauzes, sponges, probes, syringes, needles and instruments) as well as the possibility of digital palpation help with satisfactory completion of the operation. Occasionally, to facilitate the surgical manoeuvres, the gallbladder is emptied of bile through a puncture. A stable surgical field is obtained without interposition of abdominal viscera. Conventional open surgical instruments are used. Lamp lights usually suffice.

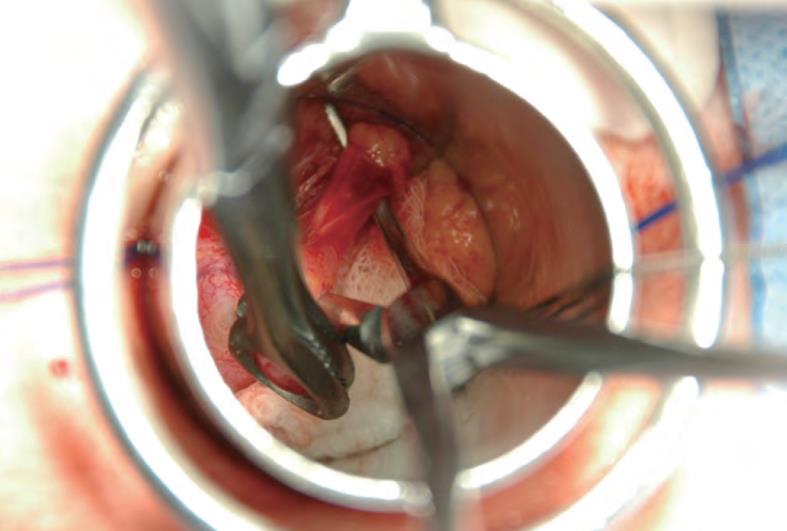

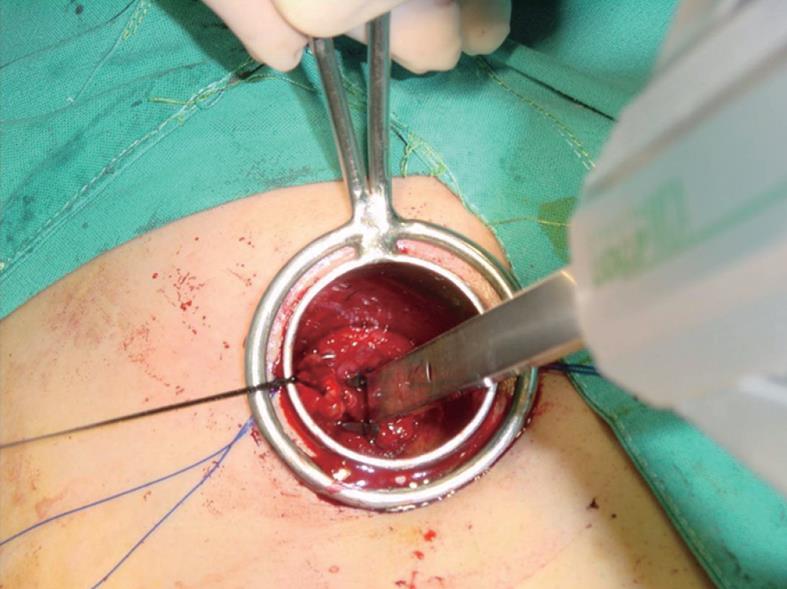

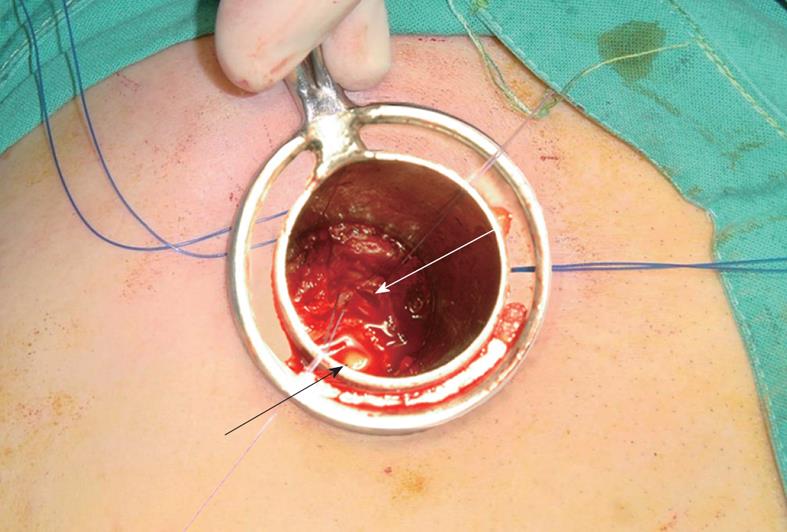

The Hartmann Pouch is grasped with tissue forceps and dissection started at the hepatocystic triangle, as in open surgery. The peritoneum is incised on the hepatocystic triangle. Fat is carefully dissected away using peanut gauze until the cystic duct and artery in all cases and, on most occasions, the common bile duct are clearly defined. At this time, the surgeon and assistant must agree on the identity of the visible anatomic structures, making sure that there are no more tubular structures entering the gallbladder[6]. The cylinder itself allows gentle displacement and traction of tissues, impeding interposition of viscera and facilitating exposure. The cystic duct and artery, once clearly identified and surrounded by using a right angle dissector (Figure 4), are sectioned between clips or ligatures (Figure 5). The gallbladder is then separated from the hepatic bed in a retrograde fashion and extracted through the incision. TC allows us to ascertain whether surgery can be completed with minimal invasion in less time than required for laparoscopy and without leaving extra holes in the abdomen.

When cholangiography is required, a transcystic catheter is kept in place with a clip (Figure 6), dye instilled and images obtained, as in open surgery. If choledocholithiasis is present, the cylinder is repositioned towards the hepatoduodenal ligament. Then, the common bile duct is opened longitudinally (Figure 7). Randall’s Forceps cannot be used through the cylinder. The manoeuvres for exploration and stone removal are done using Fogarty’s Balloons, irrigation tubes and, occasionally, a choledochoscope.

At present, most patients are discharged from hospital 8-10 h after surgery[5]. All patients are contacted by phone 24 h later and reviewed at the outpatient clinic 5 d after surgery, when the pain level is estimated using a visual analogue scale; a horizontal line, 100 mm in length, anchored by word descriptors at each end (“no pain” to the left and “very severe pain” to the right). Then, patients are followed by their family doctors who, if needed, can contact us. In different studies, patients were requested to complete and return a questionnaire about procedure satisfaction[4,5].

Our results with this technique have been previously published[4,5]. From 1993 to 2008, TC was carried out in 364 consecutive patients, including 78 acute cholecystitis, 37 acute biliary pancreatitis and 48 suspected choledocholithiasis. Transcystic cholangiography was selectively attempted in 74 patients (20.3%) and successfully obtained in all but one patient. Twenty-six patients (7.1%) underwent transcylindrical common duct exploration (and calculi removal) through a choledochotomy.

In another 23 patients (5.9%), the operation was converted into a subcostal laparotomy. There were no injuries to the main bile ducts or hemorrhagic accidents. Operating times in minutes ± SD were A) “simple cholecystectomy” without cholangiography n = 237: 43.5 ± 13.3, with cholangiography n = 30: 64.2 ± 20.7; B) “cholecystitis”n = 78: 66.2 ± 28.7; and C) “choledocholithiasis”n = 26: 117.0 ± 24.6. Postoperative complications for the respective patients in groups A, B, and C were (1) wound infection: 5 (1.9%), 0 and 0; (2) bile leaks: 2 (0.75%; one causing death, the other was revealed by a low amount of bile through the drainage that ceased in a few days), 0 and 0; (3) reoperation for bleeding: 1 (0.4%), 0 and 1 (3.8%); and (4) residual stones in the main bile ducts: 0, 0 and 1 (3.8%).

Since 2008, in 60 patients, out of 72 consecutive patients suffering from symptomatic cholelithiasis referred for elective surgery, TC was planned and started under local anesthesia plus sedation. In another 12 patients (16.7%), the operation was decided, started and completed under general anesthesia. Surgery was satisfactorily completed through the cylinder in all patients. In 13 patients (out of 60; 21.7%), local anesthesia was converted to general anesthesia. Postoperative complications were: 1 wound infection (1.7%), 2 wound seromas (3.3%), and 3 nauseas (5%). After surgery, only three patients experienced pain at rest. All but two patients were discharged from hospital on the day of surgery and all patients were satisfied with the procedure.

In our experience with using TC, we have had no cases of main bile duct injury.

The introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy revolutionized the surgical technique and, due to further innovation of instrumentation and technology, minimally invasive surgery has developed to even less invasive procedures. Conventional laparoscopy progressed to needlescopic cholecystectomy using small 2 mm instruments to reduce the discomfort from multiple incisions. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) attempts to eliminate skin incisions, the so-called “scarless surgery”; cholecystectomy being the most commonly performed NOTES procedure. Alternatively, the single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) and the natural orifice transumbilical surgery (NOTUS) are new developments using only transumbilical incisions, thereby eliminating visible abdominal scars. These new techniques are all dependent on the development of sophisticated equipment and demand growing learning curves. TC, a modification of the open minilaparotomy procedure, should be discussed within the framework of the above-mentioned developments[7].

We believe that the laparoscopic era, which began in the early nineties, has favorably influenced the mind of our surgical generation; minimal invasion is pursued, shortening recovery and dramatically changing patient’s expectations. However, at the same time, our dependence on technology to practice surgery has grown enormously. In this revolution, the industry has been able to follow (if not to advance) the surgical demands and, as a consequence, initiatives sparing material resources may be eclipsed by the most sophisticated procedures.

In a recent randomized trial of cost analysis between laparoscopic cholecystectomy and small-incision cholecystectomy[8], the mean operative times obtained were 72 and 60 min, respectively, with significantly higher cost in the laparoscopic group. Similarly, our already reported times with TC[4] are ostensibly better than those reported for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. On the other hand, our studies suggest that TC under local anesthesia is a feasible technique[5] and may have some advantages compared with cholecystectomy performed under general anesthesia, independently of the approach used. TC builds on the benefits of other techniques with the opportunity to practice under local anesthesia and that must surely translate into economic advantages and improved safety for patients. All of our patients were satisfied with TC under local anesthesia. We think that the TC technique under local anesthesia opens new opportunities for the treatment of cholelithiasis.

In relationship to patient safety, it is well recognized that, with the advent of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, bile leaks and injuries increased[9,10]. In our experience using TC in over 500 operations, we have not had a single case of main bile duct injury. Even if our patient follow up has been limited, since our working centers have been public community hospitals constituting the only health care option to patients of confined areas, the knowledge of mid or long term complications has to be seen as exhaustive.

In the present climate of cost containment, any surgical innovation must be considered globally. Concerns about a limited aspect of the final result (e.g., minimization of surgical scars) should not outweigh concerns of a procedure’s costs and risks. In this context, it is worth pointing out that application of other new procedures, such as SILS, NOTUS and NOTES, remains controversial and to date these procedures have not had the impact that was expected. All of these new developing procedures should be evaluated by controlled trials with laparoscopic cholecystectomy as the gold standard and, similarly, TC should be assessed for its potential advantages. Technical aspects and potential consequences for outcome should be analyzed in a large, controlled (three-arm randomized) study (conventional minilaparotomy compared with TC and compared with laparoscopic cholecystectomy), with details of the operative process and surgical results[7].

The authors express their gratitude to Mr. James P Nowlan for his help in translating the manuscript and to Mr. Xavier Brufau Jr. for his help in editing the figures.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is, at present, the standard technique for the treatment of symptomatic gallstones. LC vs open cholecystectomy by minilaparotomy shows no differences in mortality, complications and recovery; however, minilaparotomy compares favorably in operative time. Since 1993, the authors have been using the technique of transcylindrical cholecystectomy (TC), a modified minilaparotomy performed gas-free through a single cylinder 3.8 cm in diameter, for the treatment of cholelithiasis, cholecystitis and cholecholithiasis. Currently the authors are using TC under local anesthesia plus sedation in most patients.

Laparoscopic surgery, substituting a conventional laparotomy by several small abdominal incisions, has favorably influenced the mind of a surgical generation; minimal invasion is pursued, shortening recovery and dramatically changing patient’s expectations. However, dependence on technology and the costs to practice surgery have grown.

Needlescopic cholecystectomy using small 2 mm instruments, natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) (cholecystectomy being the most commonly performed NOTES procedure), single-incision laparoscopic surgery attempting to eliminate or minimize skin incisions; the so-called “scarless surgery”. However, the application of these new procedures is costly, remains controversial and, to date, these surgical alternatives to conventional LC have not had the impact that was expected.

Operative times and costs with TC are ostensibly better than those reported for LC or the newer alternatives. TC under local anesthesia is a feasible technique that must surely translate into economic advantages and improved safety for patients. Moreover, in relationship to patient safety, it is well recognized that with the advent of laparoscopic cholecystectomy bile leaks and injuries increased. In the experience of using TC, after more than 500 operations, the authors have not had a single case of main bile duct injury.

It is certainly conceivable that this technique might have a lower rate of injuries than LC since TC approximates OC. The authors are to be congratulated for pioneering this promising technique.

Peer reviewers: Giacomo Pata, MD, Second Department of General Surgery, Brescia Civic Hospital, P.le Spedali Civili 1, 25124 Brescia, Italy; Marcello Picchio, MD, General Surgery, Hospital “P. Colombo”, Via Orti Ginnettio 7, Velletri, 00049, Italy; Steven C Cunningham, MD, Department of Surgery, Saint Agnes Hospital, 900 Caton Avenue, Mailbox #207, Baltimore, MD 21229, United States

S- Editor Jiang L L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Keus F, de Jong JA, Gooszen HG, van Laarhoven CJ. Laparoscopic versus small-incision cholecystectomy for patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD006229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Verbesey JE, Birkett DH. Common bile duct exploration for choledocholithiasis. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88:1315-128, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Grau-Talens EJ, García-Olives F, Rupérez-Arribas MP. Transcylindrical cholecystectomy: new technique for minimally invasive cholecystectomy. World J Surg. 1998;22:453-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Grau-Talens EJ, Giner M. Transcylindrical gas-free cholecystectomy for the treatment of cholelithiasis, cholecystitis, and choledocholithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2099-2104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Grau-Talens EJ, Cattáneo JH, Giraldo R, Mangione-Castro PG, Giner M. Transcylindrical cholecystectomy under local anesthesia plus sedation. A pilot study. Endoscopy. 2010;42:395-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Strasberg SM, Brunt LM. Rationale and use of the critical view of safety in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:132-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 333] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Gouma DJ. Cholecystectomy: from open surgery to single-incision laparoscopic and transluminal endoscopic surgery. Endoscopy. 2010;42:416-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Keus F, de Jonge T, Gooszen HG, Buskens E, van Laarhoven CJ. Cost-minimization analysis in a blind randomized trial on small-incision versus laparoscopic cholecystectomy from a societal perspective: sick leave outweighs efforts in hospital savings. Trials. 2009;10:80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Richardson MC, Bell G, Fullarton GM. Incidence and nature of bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an audit of 5913 cases. West of Scotland Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Audit Group. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1356-1360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vollmer CM, Callery MP. Biliary injury following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: why still a problem. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1039-1041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |