Published online Mar 24, 2015. doi: 10.5410/wjcu.v4.i1.68

Peer-review started: May 18, 2014

First decision: June 26, 2014

Revised: October 16, 2014

Accepted: November 17, 2014

Article in press: November 19, 2014

Published online: March 24, 2015

Processing time: 311 Days and 12.3 Hours

AIM: To assess the role of PCA3 urine test in the management of patients with suspected prostate cancer after repeat negative prostate biopsies.

METHODS: Patients with suspected prostate cancer either due to high or rising prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels and with a history of prostate biopsy who were candidates for repeat procedure were prospectively recruited to undergo PCA3 urine test. The recommendations on further management including the decision whether to proceed or not to the biopsy were made based on the PCA3 score. Patients’ adherence with the recommendations and influence of the PCA3 test on clinical decision making were assessed. The contribution of the multivariate model was measured with a decision curve analysis.

RESULTS: Three hundred and fifty-six patients were recruited to the study and underwent the PCA3 test. Twenty-six percent of 263 patients underwent prostate biopsy despite the low risk designation by PCA3 and 30% of 93 men did not proceed to biopsy despite a high risk result, rendering overall adherence of 73%. The variables that significantly correlated with adherence were positive family history of prostate cancer and PSA more than 10 ng/mL. Pre-test clinical stage, the number and the results of previous biopsies were not associated with the adherence. The decision curve analysis gave identical results for cut-off points of 25 and 35. On multivariate analysis the model that included PCA3 score, serum PSA, family history and result of the previous biopsy best performed with Area Under the Curve of 0.77.

CONCLUSION: PCA3 urine test markedly outperforms PSA in a repeat biopsy setting. Urologists and patients demonstrate substantial confidence in this analysis and tend to follow its recommendations.

Core tip: PCA3 is a molecular urine test, which is performed in patients with high risk for prostate cancer. In this international prospective study we demonstrate that it has better performance than routine serum prostate specific antigen test in men with previously negative prostate biopsies. We also show that patients and physicians tend to follow the recommendations for this test.

- Citation: Yutkin V, Al-Zahrani A, Williams A, Hidas G, Martinez C, Izawa J, Pode D, Chin J. Role of PCA3 test in clinical decision making for prostate cancer diagnosis. World J Clin Urol 2015; 4(1): 68-74

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2816/full/v4/i1/68.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5410/wjcu.v4.i1.68

In recent years we have witnessed increasing debate involving the role of prostate specific antigen (PSA)-based screening in prostate cancer diagnosis, mainly following the seminal publications from the ERSPC[1] and the PLCO[2] trials. Following these and other publications, urologists have found themselves in urgent need for non-invasive diagnostic tools, in addition to PSA, in order to properly counsel their patients. The population which seems to be most in need of such tests are the patients with a high level of clinical suspicion for malignancy in spite of a prior negative biopsy, i.e., high or rising PSA following the first biopsy, or finding of multifocal high grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (HGPIN) or atypical small acinar proliferation (ASAP) on previous biopsy[3]. It has been shown that the probability of finding cancer on repeat biopsy approaches 30% and different strategies have been proposed to increase its yield[4]. On the other hand, the biopsy can be a very emotionally and physically disturbing event to the patient. This may be due to the discomfort during or following the procedure[5] or risk of more serious complications including sepsis and bleeding[6]. Therefore, much effort has been put into improving the predictive value of existing tests and into searching for a new biomarkers.

PCA3 is a non-transcribed product of the DD3 gene detected in urine. It has shown superior sensitivity and specificity over serum PSA in predicting prostate cancer both in patients after repeat prostate biopsies[7] and as a pre-biopsy screening tool[8]. Consequently, the PCA3 test was approved for use in the European Union, and recently in United States by the Food and Drug Administration. Nevertheless, the place of PCA3 in the management algorithm of patients with suspected or proven prostate cancer[9] is still under debate. The primary objective of this study was to explore the influence of PCA3 urine test on the shared decision process between the urologist and the patient and their adherence with the test’s recommendations, with the aim of assisting this tandem in resolving the issue of performing repeat prostate biopsies. The secondary objective of the study was to assess the performance of the test in a heterogeneous population of the patients at risk for prostate cancer.

The study was performed at two sites: Western University, London, Ontario, Canada, and the Hadassah and Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem, Israel. The patients were recruited prospectively between October 2007 and September 2011, after institutional ethics review boards of the respective institutions approved the study protocol independently. The urine PCA3 score test was performed in men fitting the following inclusion criteria: (1) previous benign result on prostate biopsy and PSA greater than 2.5 ng/mL or rising, compared to previous values; or (2) finding of ASAP or multifocal (two or more foci) HGPIN in the previous prostate biopsy. The first catch urine sample (20-30 mL after gentle prostate massage-3 lateral to medial strokes on each prostate lobe) of the participants was obtained. The analysis in both institutions was performed with the Gen-Probe® Progensa™ PCA3 assay[10] according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequent management was planned by the urologist who referred the patient for the PCA3 test in concert with the patient and the decision regarding whether to perform the prostate biopsy was made. The biopsy consisted of 10 to 12-cores with trans-rectal ultrasound guidance. A PCA3 score of 35 or higher was considered as a higher probability of having a subsequent positive biopsy[7]. The influence of the PCA3 test on clinical decision making was judged by concordance between the PCA3 score and subsequent management; i.e., if the patient had a PCA3 score lower than 35 (as these were the manufacturer recommendations at that time) and underwent the prostate biopsy, the decision was judged as discordant. If the patient had a PCA3 score higher than 34 and underwent the prostate biopsy, the decision was judged as concordant.

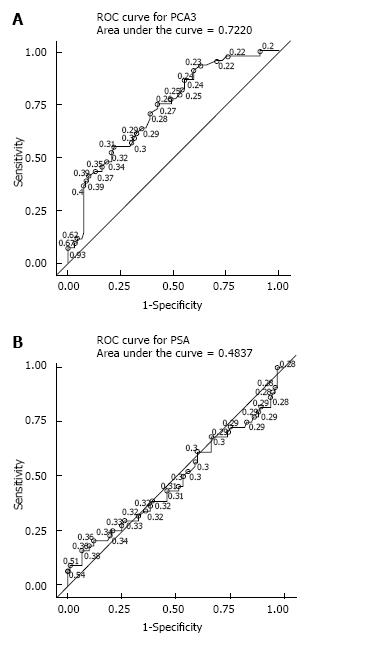

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves were constructed to assess PCA3 as a predictive factor compared with PSA. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between PCA3 and patient characteristics with biopsy outcomes. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to evaluate the effect of PCA3 on biopsy outcome adjusting for significant patient outcomes. The software used was SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States). A P value less than 0.05 was considered as significant.

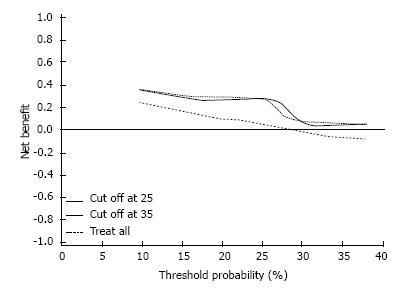

A decision curve analysis (DCA) was performed[11] to assess whether the multivariable model offers a benefit to the patient in the decision making process over PCA3 alone. The DCA was constructed by plotting the net benefit (based on the true positive and the false positive results of the test) of the PCA3 test against threshold probability of prostate cancer, at which the physician or patient would opt for a prostate biopsy. The optimal probability was set as the point with the maximum difference in the net benefit between treating all patients and treating the patients according to our model. The prediction model was created by adjusting the associated characteristics, allowing for entry of family history of prostate cancer, prior biopsy result and clinical stage.

Data on 356 patients from two centers were available for the analysis (170 from Canada and 186 from Israel). The median age was 63 (46-81) years. The majority of the men (256; 72%) had a benign histology on the biopsy prior to the PCA3 testing. An additional 100 (28%) had either multifocal HG PIN or ASAP. All patients underwent prostate biopsy before PCA3 test: 258 had 1 or 2 biopsies, 84 had 3 or 4 biopsies and 14 men had 5 or more biopsies. Forty one (11.5%) patients had a positive family history of prostate malignancy and 33 (9.3%) were currently on a 5-α reductase inhibitor for obstructive urinary symptoms.

Two hundred and sixty-three patients (74%) had a PCA3 score that put them in the lower risk group; despite that 68 (26%) men from this group underwent prostate biopsy following the PCA3 testing. Conversely, out of 93 men with a PCA3 score in the higher risk group for having prostate cancer, 65 (70%) underwent prostate biopsy in the subsequent follow up period of at least 6 mo. Thus, 260 (73%) patients were adherent with the PCA3 results recommendations and 96 (27%) were non-adherent. On the univariable analysis only a positive family history of prostate cancer and pre-test PSA value (both as a continuous variable and as a value greater than 10 ng/mL) demonstrated significant association with the adherence. These finding were confirmed on the multivariate model (Table 1).

| Adherent | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

| No (n = 96) | Yes (n = 260) | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age [mean (SD)] | 63.3 (6.2) | 62.5 (6.8) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.02) | 0.29 | NS | |

| Number of previous biopsies [mean (SD)] | 2.04 (1.12) | 2.01 (1.08) | 0.97 (0.79, 1.20) | 0.794 | NS | |

| Biopsy last result-HGPIN/ASAP | 24 (25.0%) | 64 (24.7%) | 0.99 (0.57, 1.69) | 0.955 | NS | |

| Family history | 4 (4.2%) | 38 (14.7%) | 3.96 (1.37, 11.40) | 0.011 | 3.80 (1.31, 11.05) | 0.014 |

| Last PSA ≥ 10 | 41 (42.7%) | 59 (22.8%) | 0.40 (0.24, 0.65) | < 0.001 | 0.40 (0.24, 0.67) | < 0.001 |

We performed a decision curve analysis[11] of the PCA3 test: for practical purposes, we assumed that the maximal threshold probability of having cancer on prostate biopsy was 40%, and the probability of finding HGPIN or ASAP on post-test biopsies was 37.1% (49/132). We found no difference in the net benefit with various threshold probabilities for the patients between two PCA3 score cut-off points: of 25 and 35. The optimal probability occurred at approximately 25% for both cut-off points (Figure 1).

The distribution of the post-PCA3 prostate biopsy results according to the PCA3 score is shown in Table 2. Prostate cancer was found in 44 patients, 15 of them with PCA3 less than 35. We did not find any correlation of the biopsy results with presence of inflammation (either chronic or acute), prostate gland size (as per TRUS) or with the history of 5α-reductase inhibitors intake.

| PCA3 | ||

| < 35 | ≥35 | |

| Biopsy after PCA3 test | ||

| Not done | 195 | 28 |

| Done | ||

| Normal | 45 | 22 |

| HGPIN/ASAP | 8 | 14 |

| CAP | 15 | 29 |

| Total | 68 | 65 |

| Total | 263 | 93 |

The sensitivity and specificity of the PCA3 test were 63.6% (95%CI: 47.8-77.6) and 63.0% (95%CI: 52.3-72.9), respectively with a cutoff point of 35, and 77.3% (95%CI: 62.2-88.5) and 48.9% (95%CI: 38.3-59.6), respectively with a cutoff point of 25. Univariable associations of post-PCA3 test biopsy results with different PCA3 cutoff points and other variables including various PSA levels are presented in Table 3. We found that biopsy results correlated with PCA3 score, family history of PCa, clinical stage more than T1c and existence of multifocal HGPIN or ASAP on previous biopsy. The odds ratios for univariable association of PCA3 score with biopsy result were 2.99 (95%CI: 1.42-6.30, P = 0.004) for a cutoff point of 35 and 3.26 (95%CI: 1.44-7.35, P = 0.005) for a cutoff point of 25.

| Post PCA3 biopsy result | OR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Normal benign (n = 88) | CAP (n = 44) | |||

| PCA3 [Mean (SD)] | 34.8 (34.6) | 73.3 (84.6) | 1.02 (1.01, 1.02) | 0.003 |

| PCA3 > 15.0 | 57 (64.8%) | 40 (90.9%) | 5.44 (1.78, 16.62) | 0.003 |

| PCA3 > 20.0 | 52 (59.1%) | 37 (84.1%) | 3.66 (1.47, 9.12) | 0.005 |

| PCA3 > 25.0 | 46 (52.3%) | 34 (77.3%) | 3.10 (1.37, 7.05) | 0.007 |

| PCA3 > 35.0 | 35 (39.8%) | 29 (65.9%) | 2.93 (1.38, 6.23) | 0.005 |

| PSA [Mean (SD)] | 9.3 (5.1) | 11.4 (10.1) | 1.04 (0.99, 1.09) | 0.126 |

| PSA > 4.0 | 86 (97.7%) | 42 (95.5%) | 0.49 (0.07, 3.59) | 0.481 |

| PSA > 7.5 | 48 (54.6%) | 22 (50.0%) | 0.83 (0.40, 1.72) | 0.622 |

| Inflammation | 28 (31.8%) | 16 (36.4%) | 1.22 (0.57, 2.62) | 0.602 |

| Family history | 4 (4.6%) | 7 (15.9%) | 3.97 (1.10, 14.40) | 0.036 |

| Last biopsy result-HGPIN/ASAP | 24 (27.3%) | 25 (56.8%) | 3.51 (1.64, 7.49) | 0.001 |

| Abnormal DRE | 13 (14.8%) | 14 (31.8%) | 2.69 (1.13, 6.40) | 0.025 |

The ROC analysis performed for PSA and PCA3 revealed an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.50 and 0.70, respectively (Figure 2).

Multivariable analysis was performed with the aim to determine the best model that predicts a biopsy result based on the pretest data. The best performing model included PCA3-score, serum PSA value (both as a continuous variable without particular cutoff points), positive family history of prostate cancer and finding on previous biopsy of HGPIN or ASAP. This model had an AUC of 0.77.

Out of 223 patients who did not perform post-PCA3 prostate biopsy, 89 had serum PSA levels available with at least 6 mo follow-up. The mean PSA levels dropped in this population from 7.86 to 6.22 ng/dL (P = 0.003). There were no patients with rising PSA levels during this follow-up period and there was no significant difference in the levels in the free-to-total PSA ratio between patients who underwent biopsy and those who did not.

In this study the participants mirrored the typical patient population most practicing urologists commonly face: men with high baseline or rising PSA in whom prostate biopsies showed either normal result, HGPIN or ASAP. These patients consume significant amount of ambulatory services with frequent tests and office visits. Unfortunately, despite significant health resource expenditures, the patient’s anxiety is not alleviated and their diagnosis remains equivocal. Herein, we summarized our experience with PCA3 test in an international patient cohort focusing on decision patterns of the patient-urologist tandem and on the PCA3 performance. We also searched for the best model to accurately predict the actual pathology of the prostate biopsy and analyzed it using decision curve analysis method.

Most published experience with PCA3 testing refers to patients facing repeat prostate biopsies for various reasons[7,12]. In an effort to eliminate the obvious selection bias, Roobol et al[8] analyzed the PCA3 performance in the pre-screened patient population and found it compared favorably with PSA. In this study we employed similar approach: we included both patients after a previous normal biopsies and patients who were potential candidates for repeat biopsy based on previous finding of multifocal HG PIN or ASAP. However, unlike in previous studies, we did not aim to biopsy all participants but rather left this decision to the discretion of the treating urologist and the patient. Using this approach, only 133 (37.5%) patients proceeded towards prostate biopsy. Sixty eight (51%) of them did so despite a PCA3 score less than 35, which was considered “low risk” according to the manufacturer’s recommendations at that time. With 263 men overall having a PCA3 score less than 35, it implies that 26% of men and/or their urologists decided to perform the biopsy despite the test result, rendering adherence with the recommendations with a negative test result of 74%. Conversely, 93 participants had a PCA3 score more than 34, but only 65 of them eventually underwent prostate biopsies, yielding an adherence rate with a positive test result of 70%. This is substantially lower than the figure reported by van Vugt et al[13]- these investigators had a compliance rate of 96% when the biopsy was recommended based on PSA level, digital rectal examination and trans-rectal ultrasound findings. On the other hand, the compliance with the “no biopsy” recommendation in their report was similar to ours: 64% and 74%, respectively. Our results probably reflect general reluctance of both the patients and physicians to proceed to the invasive procedures, as well as the variable confidence level in the PCA3 score results. Noteworthy, in our cohort all patients already underwent at least one prostate biopsy, thus the uncertainty and level of anxiety of being diagnosed with malignancy were lower than in the report by van Vugt et al[13], reducing even more the tendency to perform a biopsy.

Nevertheless, we found that the overall concordance of the final decision with the PCA3 score result, based on cut-off level of 35, was 73%, i.e., three quarters of the men made a choice to proceed or not with a biopsy in agreement with PCA3 result (i.e., PCA3 < 35: no biopsy performed, PCA3 ≥ 35: biopsy performed). In our opinion, this indicates some reliance on the test.

Results of our evaluation of the PCA3 test performance were similar to previously published data. The specificity and sensitivity using the manufacturer’s previously recommended cut-off point were 63.0% and 63.6%, respectively. Lowering the threshold to recently published FDA recommended 25 level obviously improved the sensitivity (77.3%) at the expense of specificity (48.9%). In univariable analysis, we found that the AUC for PCA3 was 0.70 as opposed to 0.50 for PSA. Obviously, the influence of selection bias has to be taken into account here, as all our patients already had been pre-screened with PSA and prostate biopsies with no finding of invasive carcinoma. According to the multivariable analysis, the model with a PCA3 cut-off level of 25 provided a somewhat better AUC then the model with a level of 35: 0.73 and 0.71, respectively. Interestingly, the analysis of these prediction models using DCA demonstrated virtually identical net benefit of using the test with cut-off points of 25 and 35.

This inevitable trade-off between sensitivity and specificity by means of changing the threshold level has been dealt with previously and the optimal cut-off point for the PCA3 score remains moot. Hence, we considered using the PCA3 score in our multivariable models in a continuous fashion, instead of searching for the optimal cut-off value. Interestingly, similar to the finding by Klatte et al[14], we also found that using PCA3 score continuously in the multivariable model yielded the best results, predicting the prostate biopsy results with AUC of 0.77. Other variables included in this model were PSA level (likewise in a continuous fashion), family history of prostate cancer, and previous finding of HG PIN/ASAP on prostate biopsy. Previously published externally validated multivariable prediction models[15] included , in addition to PCA3 score and PSA in their analysis (1) race, age, family history, digital rectal examination (DRE) and the result of previous prostate biopsy[16] and (2) age, DRE, prostate volume and prior biopsy result[17]. In the first study[16], the PCA3 was incorporated into the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial calculator[18] and the prostate risk was calculated both on an internal cohort of 521 patients and externally validated on an additional 443 patients. The cut-off PCA3 value used here was 25 with a resultant AUC of 0.696. In the second trial[17] of 1206 men, the authors examined three different PCA3 threshold scores: 17, 24 and 35 and concluded that the nomogram best performed using the PCA3 score of 17.

That being said, it should be mentioned that the recommended approach to the high-risk men with previous negative prostate biopsy is to perform a saturation biopsy (TRUS or trans-perineal) or to use the multiparametric MRI followed by prostate biopsy according to the findings[19]. Indeed, many of our patients did undergo MRI of the pelvis (data not shown), but the access to this test by the patients was hindered by the fact that it is not included in the health basket in both countries.

In this international prospective study we demonstrate that the urine PCA3 test has substantial influence on the pattern of decision making when considering a repeat prostate biopsy in patients suspected of having the prostate cancer. Most patients and urologists tend to follow the test results’ recommendations. In addition, we confirm the superior performance of PCA3 score test in this population, relative to serum PSA alone.

Mr. Larry Stitt for help with statistical analysis.

The currently used tumor marker for early detection of prostate cancer is a serum prostate specific antigen (PSA). Due to its relatively low specificity many men are undergoing repeat prostate biopsies, which are usually triggered by rising PSA levels or unfavorable pathology (HG PIN or ASAP). PCA3 is a urine tumor marker that reportedly has higher specificity for prediction of prostate cancer on biopsy.

PCA3 is a relatively new test and many community urologists are unfamiliar with its applications. In this field the research hotspot is to clarify the value of this test in clinical practice and further explore its clinical relevance in international cohort of men.

In this study the authors demonstrate that approximately three quarters of physicians and patients follow the recommendations on the PCA3 test results. Moreover, the performance of the PCA3 test was significantly better than that of PSA serum test.

The urine PCA3 test can be used as a better predictor of a prostate malignancy in population with low PSA test performance: after previous prostate biopsies, finding of multiple HG PIN or ASAP.

PCA3 urine test: the urine test that is specific for prostate cancer and can be used in conjunction with PSA test or as its replacement. PSA: a prostate produced protein that gains access to the blood in number of prostate benign and malignant conditions.

Very good article which adds doctor adherence and pt compliance to PCA3 testing.

P- Reviewer: Di Lorenzo G, El Sherbini MAH, Mazaris E, Shoji S S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, Tammela TL, Ciatto S, Nelen V, Kwiatkowski M, Lujan M, Lilja H, Zappa M. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1320-1328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3055] [Cited by in RCA: 2729] [Article Influence: 170.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL, Buys SS, Chia D, Church TR, Fouad MN, Gelmann EP, Kvale PA, Reding DJ. Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1310-1319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2187] [Cited by in RCA: 1991] [Article Influence: 124.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Epstein JI, Herawi M. Prostate needle biopsies containing prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia or atypical foci suspicious for carcinoma: implications for patient care. J Urol. 2006;175:820-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chun FK, Epstein JI, Ficarra V, Freedland SJ, Montironi R, Montorsi F, Shariat SF, Schröder FH, Scattoni V. Optimizing performance and interpretation of prostate biopsy: a critical analysis of the literature. Eur Urol. 2010;58:851-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Seymour H, Perry MJ, Lee-Elliot C, Dundas D, Patel U. Pain after transrectal ultrasonography-guided prostate biopsy: the advantages of periprostatic local anaesthesia. BJU Int. 2001;88:540-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Blana A, Murat FJ, Walter B, Thuroff S, Wieland WF, Chaussy C, Gelet A. First analysis of the long-term results with transrectal HIFU in patients with localised prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2008;53:1194-1201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Marks LS, Fradet Y, Deras IL, Blase A, Mathis J, Aubin SM, Cancio AT, Desaulniers M, Ellis WJ, Rittenhouse H. PCA3 molecular urine assay for prostate cancer in men undergoing repeat biopsy. Urology. 2007;69:532-535. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Roobol MJ, Schröder FH, van Leeuwen P, Wolters T, van den Bergh RC, van Leenders GJ, Hessels D. Performance of the prostate cancer antigen 3 (PCA3) gene and prostate-specific antigen in prescreened men: exploring the value of PCA3 for a first-line diagnostic test. Eur Urol. 2010;58:475-481. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Roobol MJ. Contemporary role of prostate cancer gene 3 in the management of prostate cancer. Curr Opin Urol. 2011;21:225-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Groskopf J, Aubin SM, Deras IL, Blase A, Bodrug S, Clark C, Brentano S, Mathis J, Pham J, Meyer T. APTIMA PCA3 molecular urine test: development of a method to aid in the diagnosis of prostate cancer. Clin Chem. 2006;52:1089-1095. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Vickers AJ, Elkin EB. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making. 2006;26:565-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3515] [Cited by in RCA: 3426] [Article Influence: 180.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Wu AK, Reese AC, Cooperberg MR, Sadetsky N, Shinohara K. Utility of PCA3 in patients undergoing repeat biopsy for prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012;15:100-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | van Vugt HA, Roobol MJ, Busstra M, Kil P, Oomens EH, de Jong IJ, Bangma CH, Steyerberg EW, Korfage I. Compliance with biopsy recommendations of a prostate cancer risk calculator. BJU Int. 2012;109:1480-1488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Klatte T, Waldert M, de Martino M, Schatzl G, Mannhalter C, Remzi M. Age-specific PCA3 score reference values for diagnosis of prostate cancer. World J Urol. 2012;30:405-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Perdonà S, Cavadas V, Di Lorenzo G, Damiano R, Chiappetta G, Del Prete P, Franco R, Azzarito G, Scala S, Arra C. Prostate cancer detection in the “grey area” of prostate-specific antigen below 10 ng/ml: head-to-head comparison of the updated PCPT calculator and Chun’s nomogram, two risk estimators incorporating prostate cancer antigen 3. Eur Urol. 2011;59:81-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ankerst DP, Groskopf J, Day JR, Blase A, Rittenhouse H, Pollock BH, Tangen C, Parekh D, Leach RJ, Thompson I. Predicting prostate cancer risk through incorporation of prostate cancer gene 3. J Urol. 2008;180:1303-1308; discussion 1308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chun FK, de la Taille A, van Poppel H, Marberger M, Stenzl A, Mulders PF, Huland H, Abbou CC, Stillebroer AB, van Gils MP. Prostate cancer gene 3 (PCA3): development and internal validation of a novel biopsy nomogram. Eur Urol. 2009;56:659-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio. Individualized risk assessment of prostate cancer. Available from: http: //deb.uthscsa.edu/URORiskCalc/Pages/calcs.jsp. |

| 19. | National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Prostate cancer early detection (version 1.2014). Available from: http: //www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate_detection.pdf. |