Published online Aug 8, 2013. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v2.i3.26

Revised: April 26, 2013

Accepted: May 7, 2013

Published online: August 8, 2013

Processing time: 99 Days and 8.7 Hours

Sacral dimples are the most common cutaneous anomaly detected during neonatal spinal examination. Congenital dermal sinus tract, a rare type of spinal dysraphism, occurs along the midline neuraxis from occiput down to the sacral region. It is often diagnosed in the presence of a sacral dimple together with skin signs, local infection, meningitis, abscess, or abnormal neurological examination. We report a case of acute flaccid paralysis with sensory level in a 4 mo old female infant with sacral dimple, diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging to be a paraspinal subdural abscess. Surgical exploration revealed a congenital dermal sinus tract extending from the subdural abscess down to the sacral dimple and open to the exterior with a minute opening.

Core tip: Acute flaccid paralysis with sensory level necessitates a detailed examination of the back and magnetic resonance imaging spine. Sacral dimple of more than 5 mm in diameter, lying 2.5 cm above the anus, covered by hair tufts or hemangioma, has a non visualized base, or associated with abnormal neurological examination should be further evaluated by radiology for a hidden sinus that could be a source of infection.

- Citation: Mostafa M, Nasef N, Barakat T, El-Hawary AK, Abdel-Hady H. Acute flaccid paralysis in a patient with sacral dimple. World J Clin Pediatr 2013; 2(3): 26-30

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v2/i3/26.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v2.i3.26

Acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) is a clinical syndrome characterized by rapid onset of weakness that involves the voluntary muscles and frequently includes respiratory and bulbar muscles[1]. It represents an initial manifestation of upper motor neuron lesions involving the central nervous system and spinal cord or a persistent manifestation of lower motor neuron lesions at the level of the anterior horn cell, roots and nerves, neuro-muscular junction, and muscles. Variable etiologies for acute flaccid paralysis in infants and children are listed in Table 1.

| Type of lesion | Common presenting features | Site of Lesion | Causes | Clues for diagnosis |

| UMNL | AFP and hypotonia are initial presentations for UMNL AFP occurs on the opposite side of the central nervous system lesion Spasticity develops later with hyper-reflexia and positive Babinski sign | Cerebral cortex | Intracranial hemorrhage | History of trauma |

| Signs of increased intra-cranial tension | ||||

| Signs of lateralization | ||||

| Brain tumor | History of known brain tumor | |||

| Signs of increased intra-cranial tension | ||||

| Seizure | Todd paralysis following seizure activity | |||

| Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy | History of perinatal asphyxia | |||

| Spinal cord | Spinal cord trauma | Trauma | ||

| Sensory loss/level | ||||

| Early bowel/bladder | ||||

| involvement | ||||

| Spinal tenderness, | ||||

| painful spine | ||||

| movement | ||||

| Spinal cord tumor | Sensory loss/level | |||

| Early bowel/bladder | ||||

| involvement | ||||

| Spinal tenderness, | ||||

| painful spine | ||||

| movement | ||||

| Paraspinal infection or inflammation | Fever | |||

| Sensory loss/level | ||||

| Early bowel/bladder | ||||

| involvement | ||||

| Spinal tenderness, | ||||

| painful spine | ||||

| movement | ||||

| Transverse myelitis | Fever | |||

| Sensory loss/level | ||||

| Early bowel/bladder | ||||

| involvement | ||||

| Neck stiffness | ||||

| LMNL | AFP and hypotonia are persistent presentations for LMNL Muscle weakness Hypotonia Fasciculations Decreased spinal cord reflexes | Anterior horn cell disease | Poliomyelitis | Fever |

| Preceding intramuscular injection | ||||

| Neck stiffness | ||||

| Non Poliomyelitis Eneroviruses | Fever | |||

| Enterovirus type 71 | Hand-foot-mouth disease with enterovirus type 71 and Coxsackie infections | |||

| Coxsackie viruses | Myocarditis and/or hepatitis | |||

| Echoviruses | Parotitis | |||

| Mumps virus | ||||

| Peripheral Nerve | Guillain-Barré syndrome | Preceding infectious | ||

| prodrome/vaccination | ||||

| Prominent autonomic | ||||

| signs/symptoms | ||||

| Ascending weakness | ||||

| Facial weakness | ||||

| Myalgia | ||||

| Neck stiffness | ||||

| Peripheral nerve toxins | Exposure | |||

| Acute intermittent porphyria | Intermittent nature | |||

| Abdominal pain | ||||

| Peripheral neuropathies | ||||

| Central nervous system signs (seizures, mental status changes, cortical blindness, and coma) | ||||

| Neuromuscular junction disorders | Botulism | Exposure | ||

| Constipation | ||||

| Descending weakness | ||||

| Facial weakness | ||||

| Myasthenia gravis | Prominent and early | |||

| ptosis | ||||

| Facial weakness | ||||

| Fluctuating symptoms, | ||||

| fatigability | ||||

| Organophosphate poisoning | Exposure | |||

| Myosis | ||||

| muscle fasciculation | ||||

| Neurotoxic snake envenomation | Exposure | |||

| Site of bite | ||||

| Muscle | Rhabdomyolysis | Muscle tenderness | ||

| Myositis | Fever | |||

| Muscle tenderness | ||||

| Familial periodic paralysis | Preserved muscle stretch reflexes | |||

| Others | Electrolyte disturbance | Diarrhea | ||

| Drug-related | Exposure |

The urgency to arrive at the diagnosis and the choice of the initial investigations require a thorough patient history and a detailed clinical examination to reach the probable neuro-anatomical level of the lesion and the accounting etiology. Accordingly, a step wise and judicious use of investigations helps to reach the diagnosis with the minimum use of resources. Suggested approaches for diagnosis of AFP in children recommend starting by identifying evidence of spinal cord lesion through the presence of sensory level on examination, which then necessitates magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation of the spine to differentiate between compressive and non-compressive myelopathies[1,2]. We report a case of acute flaccid paralysis with sensory level in a female infant with sacral dimple, diagnosed by MRI to be a compressive myelopathy secondary to paraspinal abscess.

A 4 mo old female infant presented with acute flaccid paralysis of both lower limbs following 15 d of high grade fever, rhinorhea, cough, and irritability. She received antibiotic for 10 d with no response. There was no associated weakness of the upper limbs, no respiratory distress, no constipation, but decreased urine output.

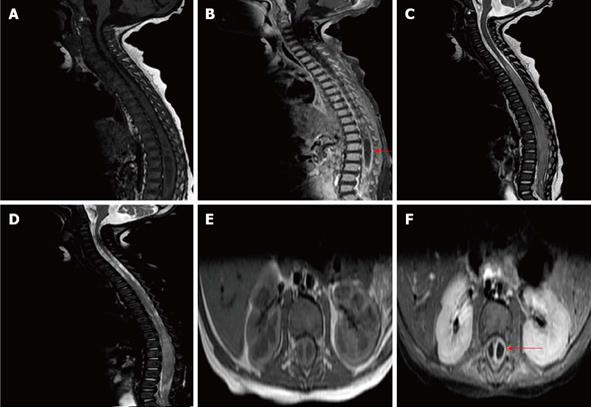

General examination revealed normal growth parameters and normal consciousness level. Examination of the back showed a sacral dimple of 7 mm in diameter, lying 4 cm above the anus, not covered by hair tufts or hemangioma and with an apparently intact base (Figure 1). Neurological examination was significant for atonia and areflexia of both lower limbs, loss of sensation below the umbilicus, absent abdominal and anal scratch reflexes together with urine retention. Tone, reflexes and sensation were intact in the upper half of the body.

Her laboratory investigations were significant for leucocytosis with prominent neutrophilic count, high erythrocyte sedimentation rate and positive C-reactive protein. Magnetic resonance imaging of the spine revealed a subdural abscess extending from dorsal 4 to sacral 1 and syringohydromyelia at the same level (Figure 2).

Surgical exploration, for evacuation of the subdural abscess, showed a congenital dermal sinus tract extending from the subdural abscess down to the sacral dimple and open to the exterior with a pin point hall. Surgical excision of the abscess and the sinus was done with culture of drained purulent fluid. This revealed a heavy growth of Candida infection. Following surgical excision and antifungal therapy, the patient regained full range of movements, tone and sensation in her lower limbs as well as normal voiding acts and no further urine retention.

Sacral dimples, also known as sacrococcygeal or coccygeal dimples or pits, are the most common cutaneous anomaly detected at neonatal spinal examination[3]. Sacral dimple may be associated with a congenital dermal sinus which is a tract lined by stratified squamous epithelium[4]. The most widely accepted theory regarding the embryogenesis of congenital dermal sinus tracts proposes that they arise through faulty disjunction of the neuroectoderm from the overlying cutaneous ectoderm between the third and eighth week of gestation[5,6]. They have been previously reported along the midline neuroaxis from the nasion and occipital area down to the lumbar and sacral regions[4], with the highest frequency (75%) in the lumbar and lumbosacral region[6]. The majority of these tracts terminate in a dermoid or epidermoid cyst, however some tracts incorporate a cutaneous ectoderm from the dorsal midline skin that extends for a variable distance into the underlying mesenchymal tissue and in many instances penetrates the dura to end within the thecal sac adjacent to or continuous with the neural tube[5].

Literature evidence for the association between sacral dimple and congenital dermal sinus is controversial. The association between sacral dimples and occult spinal dysraphism was failed to be proven in five different case series including over 1300 children[3,7-10]. However, Kriss et al[7] examined 207 neonates with 216 cutaneous stigmata; the most common of which was midline dimple and found that simple midline dimples indicate low risk for spinal dysraphism. They reported atypical dimples particularly those that are large (> 5 mm), high on the back (> 2.5 cm from the anus), or appear in combination with other lesions to be associated with a high risk for spinal dysraphism. Accordingly, authors recommended that dimples of large size, located at a higher spinal level, or associated with other cutaneous stigmata should be investigated.

A wide spectrum of clinical manifestations can occur, ranging from asymptomatic dermal sinus to serious complications. There is no apparent timeframe for an asymptomatic lesion to later become symptomatic. Symptomatic sinuses may present clinically with varying degrees of drainage from their cutaneous openings, recurrent bouts of septic or aseptic meningitis, or mass effect on the cerebrospinal fluid pathways secondary to subdural abscesses and consequent hydrocephalus[11]. The slow growth rate of these abscesses often masks their presentation for years, although there are some patients which present with acute neurological deterioration[4,12]. Our case represents an example of the acute neurological manifestations of sacral sinus tracts. Similar to our case, Kurisu et al[13] reported a case of repeated fever and rapidly progressive paraplegia in a one year old male infant with lumbo-sacral dimple proved by MRI to be an intraspinal and intramedullary abscess where surgical exploration revealed an underlying sinus tract.

Ultrasonography is the screening modality of choice for the infant with atypical sacral dimples. The presence of an intra-spinal mass, abnormal position or shape of the conus, or a thick filum necessitates MRI study[14]. Magnetic resonance imaging has become the reference study technique because of its ability to accurately depict the extent of the sinus tract and associated lesions[12]. Magnetic resonance imaging accurately differentiate between compressive and non compressive diseases of the spinal cord. Chen et al[15] investigated the MRI features of enterovirus 71 related acute flaccid paralysis in patients with hand-foot-mouth disease and found that MRI could efficiently show a characteristic pattern of affection to the anterior horn regions and ventral root of the cervical spinal cord and spinal cord below T9 level. Therapy is almost always surgical, aiming for obliteration of the tract with elimination of the communication between the skin and the neural structures. The earlier the lesion is detected and corrected, the less likely any long-term morbidity may develop.

In conclusion, acute flaccid paralysis with sensory level necessitates a detailed examination of the back and spinal MRI. Sacral dimple of more than 5 mm in diameter, lying 2.5 cm above the anus, covered by hair tufts or hemangioma, has a non visualized base, or associated with abnormal neurological examination should be further evaluated by radiology for a hidden sinus that could be a source of infection.

P- Reviewers Orlacchio A, Sijens PE S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Lu YJ

| 1. | Marx A, Glass JD, Sutter RW. Differential diagnosis of acute flaccid paralysis and its role in poliomyelitis surveillance. Epidemiol Rev. 2000;22:298-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Singhi SC, Sankhyan N, Shah R, Singhi P. Approach to a child with acute flaccid paralysis. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:1351-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Weprin BE, Oakes WJ. Coccygeal pits. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dias MS, McLone DG. Normal and abnormal early development of the nervous system. McLone, editor. Philadelphia: WB Saunders 2001; . |

| 5. | Ackerman LL, Menezes AH. Spinal congenital dermal sinuses: a 30-year experience. Pediatrics. 2003;112:641-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jindal A, Mahapatra AK. Spinal congenital dermal sinus: an experience of 23 cases over 7 years. Neurol India. 2001;49:243-246. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kriss VM, Desai NS. Occult spinal dysraphism in neonates: assessment of high-risk cutaneous stigmata on sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:1687-1692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gibson PJ, Britton J, Hall DM, Hill CR. Lumbosacral skin markers and identification of occult spinal dysraphism in neonates. Acta Paediatr. 1995;84:208-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Herman TE, Oser RF, Shackelford GD. Intergluteal dorsal dermal sinuses. The role of neonatal spinal sonography. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1993;32:627-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Robinson AJ, Russell S, Rimmer S. The value of ultrasonic examination of the lumbar spine in infants with specific reference to cutaneous markers of occult spinal dysraphism. Clin Radiol. 2005;60:72-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ansari S, Dadmehr M, Nejat F. Possible genetic correlation of an occipital dermal sinus in a mother and son. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:326-328. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Nejat F, Dias MS, Eftekhar B, Roodsari NN, Hamidi S. Bilateral retro-auricular dermal sinus tracts with intradural extension. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:163-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kurisu K, Hida K, Yano S, Yamaguchi S, Motegi H, Kubota K, Iwasaki Y. [Case of a large intra and extra medullary abscess of the spinal cord due to dermal sinus]. No Shinkei Geka. 2008;36:1127-1132. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Korsvik HE, Keller MS. Sonography of occult dysraphism in neonates and infants with MR imaging correlation. Radiographics. 1992;12:297-306; discussion 307-308. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Chen F, Li JJ, Liu T, Wen GQ, Xiang W. Clinical and neuroimaging features of enterovirus71 related acute flaccid paralysis in patients with hand-foot-mouth disease. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2013;6:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |