Published online Mar 9, 2024. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v13.i1.89086

Peer-review started: October 20, 2023

First decision: December 29, 2023

Revised: January 6, 2024

Accepted: February 18, 2024

Article in press: February 18, 2024

Published online: March 9, 2024

Processing time: 139 Days and 2.5 Hours

A progressive decrease in exclusive breastfeeding (BF) is observed in Latin America and the Caribbean compared with global results. The possibility of being breastfed and continuing BF for > 6 months is lower in low birth weight than in healthy-weight infants.

To identify factors associated with BF maintenance and promotion, with particular attention to low- and middle-income countries, by studying geographic, socioeconomic, and individual or neonatal health factors.

A scoping review was conducted in 2018 using the conceptual model of social determinants of health published by the Commission on Equity and Health Inequalities in the United States. The extracted data with common characteristics were synthesized and categorized into two main themes: (1) Sociodemographic factors and proximal determinants involved in the initiation and maintenance of BF in low-birth-weight term infants in Latin America; and (2) individual characteristics related to the self-efficacy capacity for BF maintenance and adherence in low-birth-weight term infants.

This study identified maternal age, educational level, maternal economic capacity, social stratum, exposure to BF substitutes, access to BF information, and quality of health services as mediators for maintaining BF.

Individual self-efficacy factors that enable BF adherence in at-risk populations should be analyzed for better health outcomes.

Core Tip: Analyzing sociodemographic and individual conditions for maintaining breastfeeding (BF) is fundamental for meeting the second sustainable developmental goal. However, analysis of the feeding behavior in low-birth-weight term newborns in Latin America is limited. Few studies have assessed the mediating factors for BF maintenance, paving the way for the challenges faced by at-risk populations, mainly in developing countries. Evidence-based interventions should be based on an understanding of the social and individual factors affecting feeding practices for at-risk populations.

- Citation: Avendaño-Vásquez CJ, Villamizar-Osorio ML, Niño-Peñaranda CJ, Medellín-Olaya J, Reina-Gamba NC. Sociodemographic determinants associated with breastfeeding in term infants with low birth weight in Latin American countries. World J Clin Pediatr 2024; 13(1): 89086

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v13/i1/89086.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v13.i1.89086

The United Nations Children’s Fund and the World Health Organization estimated that one in seven live births will be underweight by 2020, which is equivalent to 19.8 million babies worldwide. The prevalence of all low-birth-weight infants with stunting and wasting in early childhood is approximately 70% in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa[1]. The variation has been minimal in Latin America, maintaining a prevalence between 12% and 9.6% over the last decade[1]. No region has experienced significant changes in the prevalence since 2012, preventing the achievement of the low-birth-weight target set by the World Health Assembly for 2030[1]. In this context, low birth weight is considered a public health problem associated with the newborn’s well-being because of the high risk of acquiring diseases or disabilities that affect physical and cognitive development and as a predictor of morbidity and mortality[2].

In this sense, access to breastfeeding (BF) is essential and indicates better child health outcomes. However, the likelihood of being breastfed and continuing BF for > 6 months in low-birth-weight infants is lower than that in healthy-weight infants. Underweight children without adequate nutrition have an increased risk of fetal and neonatal death in the first years of life, physical and cognitive growth retardation, and increased chronic diseases later in the perinatal period, childhood, and adulthood[3].

In this regard, the literature has shown the benefits of BF in newborns and infants, and sociodemographic determinants associated with its maintenance are of particular relevance, mainly in low- and middle-income regions[4]. The individual characteristics of the mother and newborn, associated with cultural feeding practices, as well as social and health system determinants, are some factors that influence BF practices[5].

Smoking, schooling, obstetric conditions, newborn complications that require separation from the dyad, and BF education have been identified as moderating individual characteristics factors of feeding practices of the mothers associated with the initiation and continuation of BF[6]. Moreover, conditions specific to the BF woman, such as self-efficacy and her family nucleus, especially the emotional and mental situation, can contribute to the abandonment of BF[6]. Geographical, socioeconomic, and individual factors and health complications are among the factors associated with late or impossible BF initiation in low-birth-weight infants during the first hour postpartum[7,8].

The trend in improving BF duration in Latin America and the Caribbean depends not only on the policies implemented by each government but also on the particularities of population subgroups[9]. However, studies related to BF and nutrition in low-birth-weight term infants have generally been limited, mainly due to the difficulty in generating reference parameters to observe nutritional behaviors and their impact on the neuro-physical development of the child; therefore, efforts have been directed to preterm infants and those with adequate weight for gestational age, for whom follow-up scales have been constructed[10,11]

Global studies have identified the significant variability of feeding practices in low-birth-weight populations[9], reporting the prevalence of BF and its association with socioeconomic conditions of the environment. However, the findings are more limited to Latin America, a region characterized by vast social inequalities, mainly to materializing social policies affecting the health and educational system and generally satisfying basic needs[12].

In this context, aspects related to health equity are considered as determinants. The absence of social, economic, and demographic guarantees can influence the initiation and adherence to BF in low-birth-weight infants[9]; some cultural and social factors can interfere with the promotion and support of BF to ensure adherence. Consequently, sociodemographic determinants and individual conditions associated with BF should be analyzed in low-birth-weight term infants in Latin American countries from a health inequity perspective.

A scoping review was performed based on five phases proposed by Arksey and Malley[13] and reports according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement[14].

For the present review, the 2018 conceptual model of social determinants of health published by the Commission on Equity and Health Inequalities in the United States was adopted. The social position was considered a central component and an explanatory construct that allows determining the representations of inequality, including income, education, occupation, gender, ethnic belonging, and other dimensions, to determine the health distribution and well-being in the population mediated by the so-called proximate or intermediary determinants, which include material circumstances, social cohesion, human behavior, genetic inheritance, and health system organization[15].

The concept of self-efficacy was determined according to Bandura (1987), who defined it as judgments of each individual about their abilities and use to organize and execute actions with the highest possible performance, contributing to the achievement of human accomplishments and increased motivation[16].

This review addresses the following research questions: (1) What sociodemographic factors are involved in initiating and maintaining BF in low-birth-weight term infants in Latin America; (2) What proximal health determinants are involved in the inequality of BF maintenance and adherence in low-birth-weight term infants; and (3) What individual characteristics are related to self-efficacy for BF maintenance and adherence in low-birth-weight term infants?

The search strategy included articles published in Medline, Embase, OvidSP, CINAHL, and the Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Database using the Medical Subject Headings MeSH and DeCS terms reference list. The combinations of search terms using Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were as follows: Social determinants of health AND self-efficacy AND breastfeeding AND infant, and low birth weight (Supplementary material). Additional information was obtained by manually searching the reference lists of relevant articles. Full-text articles published up to 2022 using qualitative and quantitative methodologies were considered. The search strategy was limited to English and Spanish studies. Commentaries, editorials, opinion articles, and book chapters were excluded.

In this phase, the following aspects were contemplated: (1) Construction of search formulas elaborated by an experienced research team member; (2) Identification of the search strategy by database exploring the best scientific evidence; and (3) Analysis of titles and abstracts to select relevant studies. Subsequently, three researchers assessed the titles and abstracts of the identified publications and independently performed data extraction. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus.

The organization and thematic analysis of the scientific evidence was carried out in the Excel program with data extraction such as bibliographic source, study purpose, country of origin, study type, design, sociodemographic characteristics, cultural characteristics, type of BF, and individual aspects of the mother in terms of self-efficacy and knowledge gaps (Table 1). During the process, three reviewers compared the authors’ contributions and sociodemographic characteristics of individual conditions responsible for initiating and sustaining BF in low-birth-weight term infants.

| Ref. | Location | Study design | Type of Sampling | Sample size LWB | Control group | Measurements | Analysis |

| Lizarazo et al[2], 2023 | Colombia | Observational | Convenience | 25 | No | Investigator-designed survey. Medical records | Descriptive analysis |

| Ortelan et al[18], 2020 | Brazil | Observational | Probabilistic | 2370 | No | Questionnaire on sociodemographic characteristics of mothers and breast milk consumption. BF prevalence survey | Poisson regression |

| Agudelo et al[23], 2021 | Colombia | Clinical trial | Probabilistic | 297 | Yes | Infant BF assessment tool | Cox proportional hazards analysis. Cox regression models |

| Montoya et al[24], 2020 | Colombia | Observational | Convenience | 52 | Yes | Investigator-designed survey. Medical records | Descriptive analysis |

| Charpak and Montealegre-Pomar[25], 2023 | Colombia | Observational | Convenience | 57.154 | Yes | Griffiths test. INFANIB test | Bivariate analysis |

| Sequeiros et al[26], 2023 | Peru | Observational | Convenience | 489 | No | Demographic and family health survey. Household questionnaire. Individual woman questionnaire. Health questionnaire | Bivariate and multivariate analysis |

| Ortiz Romaní and Loayza Alarico[20], 2023 | Peru | Observational | Convenience | 531 | No | National database | Binary logistic regression |

| Wormald et al[19], 2021 | Chile | Observational | Convenience | 118 | No | State trait anxiety inventory. Beck depression inventory; BDI-I. BF self-efficacy scale for mothers with hospitalized preterm infants | Multinomial logistic regression |

| Javela Rugeles et al[21], 2019 | Colombia | Observational | Convenience | 90 | No | Medical records | Descriptive analysis |

| Mangialavori et al[22], 2022 | Argentina | Observational | Probabilistic | 1044 | No | Investigator-designed survey. Medical records | Descriptive analysis |

| Ortelan et al[17], 2019 | Brazil | Observational | Probabilistic | 2112 | Yes | Medical records | Multilevel Poisson regression models |

The extracted data with common characteristics were synthesized and categorized into two main themes: (1) Sociodemographic factors and proximal determinants involved in the initiation and maintenance of BF in low-birth-weight term infants in Latin America; and (2) Individual characteristics related to the capacity for self-efficacy for BF maintenance and adherence in low-birth-weight term infants (Tables 2 and 3).

| Ref. | BF results | Mother's socio-demographic characteristics | Associated proximate determinants | ||

| Age | Education | Social stratum | |||

| Lizarazo et al[2], 2023 | Information on prenatal BF: 67%. No information on BF: 32.3%. 1-4 prenatal checkups: 43.5%. More than 4 controls: 13.7%. Time to initiation of BF at birth: < 1 h: 33.9%. 1-12 h: 33.1%. > 12 h: 33%. Previous history of BF. BF up to 6 months: 58.5%. BF between 3 and 6 months: 18.5%. No previous BF: 7.1% | Average 28 ± 7.3 years | High School: 38.7%. Technical education: 19.4%. Professional: 31.5% | Low stratum: 31.5%. Very low stratum: 40.3% | Work-related causes: 10.5%. Study: 0.8%. Partially absent mother: 0.8% |

| Ortelan et al[18], 2020 | BF prevalence: 54.5% | Age in years (%). < 20: 18.1%. 20-35: 66.9%. > 35: 15% | High School: 47.1%. Professional: 12.5% | No report | Working outside the home (PR = 1.28; 95%CI 1.11-1.48). Residence in municipalities with a prevalence of child undernutrition below 10% (PR = 1.66; 95%CI 1.23-2.24). Mothers with 12 years of schooling or more (PR = 1.35; 95%CI 1.16-1.58) |

| Agudelo et al[23], 2021 | Average duration of exclusive BF: 5 months. BF up to 3 months: 78%. No BF up to 3 months: 19.5%. BF up to 6 months: 25%. No BF up to 6 months: 71% | Median age (IQR). Intervention group: 23 years (21-29). Control group: 24 years (20-25) | Elementary education: 11%. High school: 60%. Technical education: 13%. Professional: 16% | Low stratum: 64.3%. Very low stratum:33.6% | Working outside the home |

| Sequeiros et al[26], 2023 | Interruption of exclusive BF: 26%. Initiation of BF at birth: Immediately: 70.1%. > 1 h: 29.8% | Age in years of mothers who discontinued BF. < 18: 31.7%. 18-25: 27.7%. 26-35: 25.7%. 36-45: 25.0% | Elementary education: 20.5%. High school: 26.7%. Professional: 31.2% | Low stratum: 22%. Middle stratum: 33%. High stratum: 36% | Higher educational level (PRa: 1.55; 95%CI: 1.06-2.27). Rich vs poor family wealth index (RPa: 1.13; 95%CI: 1.03-1.25). Residing in the jungle (RPa: 0.77; 95%CI: 0.71-0.84). Native indigenous language (PRa: 0.82; 95%CI: 0.75-0.91). BF training (PRa: 0.88; 95%CI: 0.82-0.94). Infant with health insurance (PRa: 0.91; 95%CI: 0.84-0.97) |

| Ortiz Romaní and Loayza Alarico[20], 2023 | Prevalence of early initiation of BF: 49.6%. | Age in years (%). 12-14: 0.09%. 15-19: 6.11%. 20-49: 93.80% | High School: 47.2% | Low stratum: 47%. Middle stratum: 21.3%. High stratum: 31.5% | Factors interfering with early initiation of BF: Living in rural area (ORa: 2.37) and jungle (ORa: 1.72). High wealth index. Access to health services and prenatal care |

| Javela Rugeles et al[21], 2019 | Children with BF for one year maintain anthropometric measurements below -2 SD. | Age in years (%). < 20: 17%. > 35: 18% | High school: 64%. Elementary education: 18%. Technical education: 18% | Very low stratum: 57%. Low stratum: 36%. High stratum: 8% | Low social stratum |

| Mangialavori et al[22], 2022 | Prevalence of BF: 34.7% (95%CI: 31.6-37.9). BF before the first hour of birth: 40.1% (95%CI: 36.9-43.4) | No report | Elementary education: 9.3%. High school: 91.3% | No report | Mother's educational level |

| Ortelan et al[17], 2019 | Prevalence of BF: 43.9% | Age in years (%). < 20: 21.3%. 20-35: 65.3%. > 35: 13.4% | High School: 47.6% | No report | Factors favoring BF practices: Age between 20-35 years (PR = 1.35; 95%CI: 1.09-1.69). Work at home. Birth in BF-friendly hospital services. Increased availability of human milk banks per 10000 inhabitants |

| Ref. | Reason for BF desertion/difficulties | Barriers | Enablers |

| Lizarazo et al[2], 2023 | Perception of low milk production. Newborn's feeling of not satiety. Newborn rejection. Maternal decision | Mother's mood as an influence on BF practice. Work commitments | Family support for housework |

| Ortelan et al[18], 2020 | Age, education, multiparity | Inadequate supplementary feeding | High educational level |

| Agudelo et al[23], 2021 | Supported to stimulate BF in the first hour of life | Interference with newborn routines; availability of time for skin-to-skin contact at birth; obesity; smoking | Educational support. Immediate skin-to-skin contact in the maternity ward |

| Montoya et al[24], 2020 | Newborn hospitalization for low birth weight. Maternal hospitalization. BF technique. No previous experience in BF | Feeding with milk substitutes suggested by health personnel | Mother's willingness to breastfeed. Support from family and health personnel. Mother's previous BF experience |

| Charpak and Montealegre-Pomar[25], 2023 | Respiratory pathology of the newborn | Pathologies of the newborn | Monitoring and follow-up of the health of low-birth-weight newborns and maternal care in mother Kangaroo programs. |

| Sequeiros et al[26], 2023 | Lack of knowledge of BF during pregnancy | Mothers with higher education. Infant only child. Age < 18 years. Birth by caesarean section | Early BF training during pregnancy. Early initiation of BF |

| Ortiz Romaní and Loayza Alarico[20], 2023 | Cesarean delivery. First gestation. Pre-milk feeding of the newborn | Lack of BF skills. Limitations for skin-to-skin contact in the first hour of life | Develop skills and abilities in relation to the promotion of BF. Management of the mother's own symptoms that are contemplated in the different prenatal services and delivery room |

| Wormald et al[19], 2021 | Manifestation of emotional symptoms | Exposure to triggers for depression or anxiety | Self-efficacy |

| Javela Rugeles et al[21], 2019 | Newborn comorbidities | Extreme ages. No support during the first month of the newborn's life | Family support |

| Mangialavori et al[22], 2022 | Cesarean delivery | Limitations to BF in the first hour of life. Separation of mother-infant dyad > 4 h | Educational level |

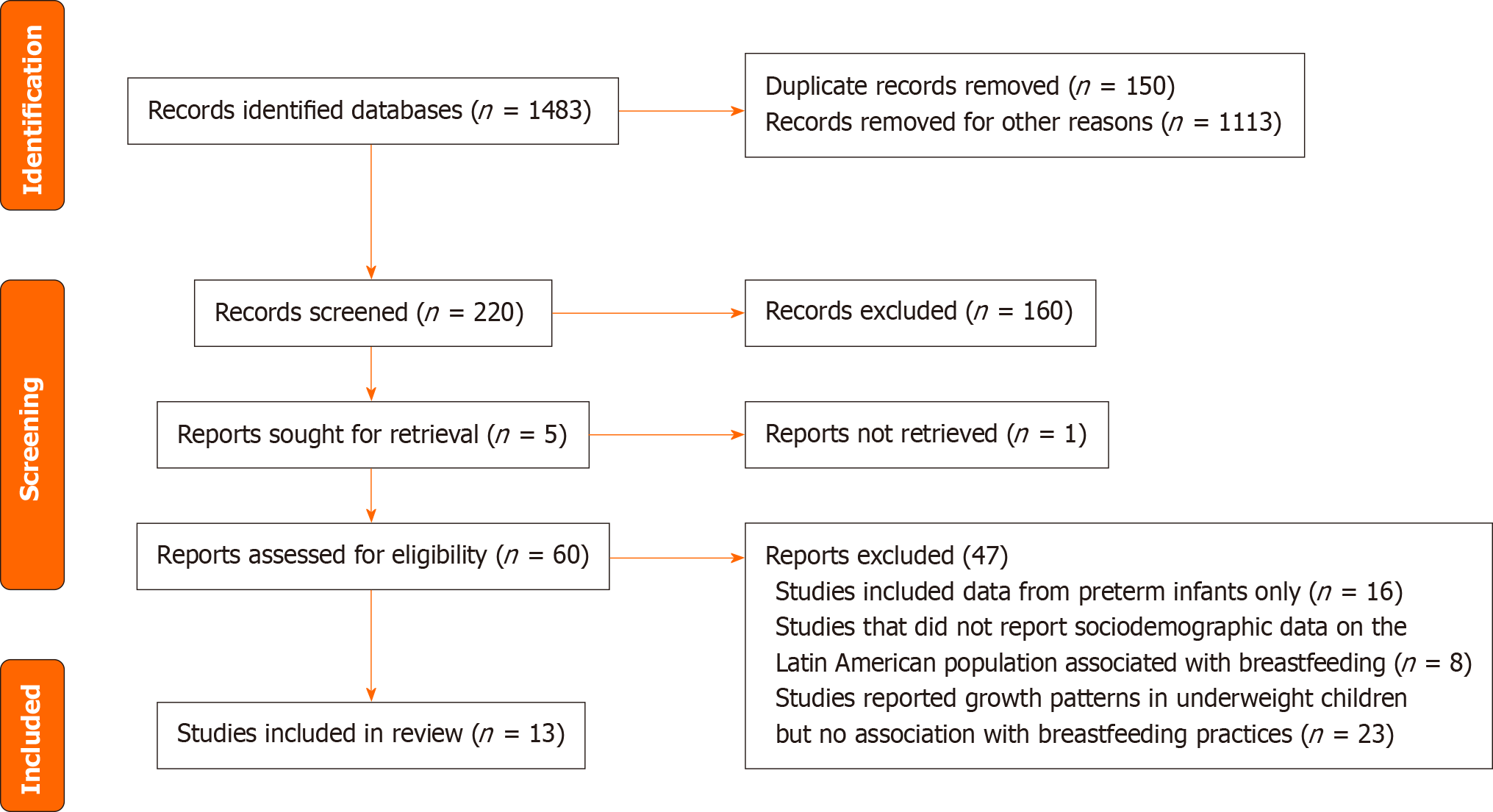

The search strategy identified 1483 articles; 1263 studies were excluded. Sixty full-text articles were reviewed, and 47 articles were excluded. Eleven studies were finally included after applying the study criteria for synthesizing the results (Figure 1). One clinical trial was identified in the 11 selected studies. Most participants were recruited through convenience sampling, and 46% used comparison groups. Table 1 shows the primary characteristics of the included studies.

Seven observational studies have reported sociodemographic factors and proximal determinants associated with BF adherence and maintenance in low-birth-weight term infants. Studies have focused on identifying the prevalence of BF, feeding patterns, and associated factors for its maintenance. Most BF reported in the study population ranged from 34.7% to 58.5% at 6 months. The primary mediators of maintaining BF were educational level, access to health services, and social status[2,17-22]. Agudelo et al[23] conducted a randomized clinical trial on the effect of the time of initiation of skin-to-skin contact at birth, immediately compared to early, on the BF duration in term newborns, analyzing the percentage of infants exclusively breastfed at 3 months and the period in months of exclusive BF. The results showed that skin-to-skin contact, regardless of the initiation time, improved the percentage of exclusively breastfed infants in at-risk populations[23] (Table 2).

Individual characteristics associated with BF maintenance in the study population were mainly related to maternal age and education, perception of BF success, type of birth, pathologies related to the newborn or mother, and previous BF experience. Some barriers to BF adherence were associated with the use of breast milk substitutes, advanced ages, separation of the mother–child dyad, and compromised emotional states of the mother. Facilitators for achieving self-efficacy levels were family and social support, maternal education and experience, and adequate follow-up of the mother’s and newborn’s health status by health services[2,17,19-26] (Table 3).

Low birth weight is a public health problem associated with a series of determinants that condition a child’s health status in the short and long term, representing a challenge for the health system. This review identified the social and individual determinants in mothers who modify BF practices for its maintenance and adherence in an underexplored at-risk population.

The study revealed that certain social factors hinder exclusive BF within the first 6 months of life. These factors contribute to the low BF rates in Latin America. Demographic factors such as advanced age, mainly in adolescence, low family income, ethnicity, marital status, support, and orientation of health services showed a direct relationship with feeding outcomes in the study population. Various studies have shown how social factors, such as marital status, impact BF effectiveness. These factors are related to family stability and economic situations for child rearing and protection[27].

In this context, the educational level is an important factor. Studies report a greater tendency for early discontinuation of exclusive BF during the first hour up to 6 months of life in mothers with low educational levels with lower rates of BF in low-birth-weight infants compared with full-term infants with adequate weight for gestational age[28]. However, a pattern of BF abandonment is also observed in pregnant women with higher educational levels. BF policies focused on vulnerable populations and work activities specific to this educational level may explain this phenomenon; therefore, the needs of the people should be recognized in occupational terms and according to the economic growth of the regions[29].

Consequently, access to quality health services is essential. Our results showed positive effects in mothers who received education on the importance and benefits of BF during follow-up, maternal perinatal care, and newborn hospitalization. Intervention strategies based on population needs and geographic diversity by analyzing the social structure’s multiple components can significantly promote BF adherence and maintenance in the study population[30]. However, these intervention processes should be accompanied by the joint construction of skills to develop self-efficacy to minimize the risk of abandonment of good feeding practices in the infant population[31]. Additionally, conditions of the newborn and mother related to the manifestation of pathologies should be considered to strengthen the response capacity and BF technique during the healthcare process to ensure adherence to hospital discharge[27,32].

In this sense, family and health personnel support are essential for the mother to make the right decisions regarding BF. The early diagnosis of risk factors associated with individual characteristics can become a protective factor that contributes to the management of deficient emotional states and, by extension, positively stimulates confidence and security skills to continue BF[33]. In addition, involving parents in the orientation process for BF techniques and encouraging active participation helps foster positive outcomes for the couple. BF self-efficacy in low-birth-weight infants is considered an emotional factor that influences milk production and prolongs BF exclusivity and maintenance, enabling empowerment in the BF process to overcome obstacles and difficulties for comprehensive care[33]. Implementing health interventions on the overall care of low-birth-weight newborns at home from a skilled approach allows interaction in health management with the child. Therefore, mothers’ self-efficacies should be assessed to detect the risk of BF abandonment and facilitate a safe transition based on the population’s needs[34].

Diagnosing the proximal determinants that mediate BF adherence and maintenance using a differential approach and a self-efficacy skills development perspective is essential for the comprehensive care of low-birth-weight term infants in developing countries.

Proximal determinants define the maintenance of breastfeeding (BF) in infants with low birth weights in the Latin American population.

Equity in health is an essential issue to address to achieve sustainable development goals regarding the food security of the population at risk.

To identify proximal determinants associated with BF maintenance in low birth weight infants at term. Little literature describes how proximal determinants affect BF maintenance in populations at nutritional risk. Determining the epigenetic conditions involved in infant feeding practices is essential to develop good health practices.

A scoping review was performed according to the five phases proposed and reporting according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews for systematic reviews and meta-analyses statement.

Proximal determinants related to social position are involved in the maintenance of BF in population at nutritional risk. Despite the fact that BF is considered the best food for the population at nutritional risk, the prevalence at a global level does not allow achieving sustainable development objectives. Individual factors and self-management skills should be promoted to reinforce infant feeding practices.

The analysis of social inequalities is fundamental to reduce the gaps in the provision of health services. A comprehensive approach with a differential emphasis based on individual and collective response capacity is a priority for the formulation of public health policies.

To analyze individual and collective differences based on the epidemiological behavior of possible nutritional affectations in the population at risk. Develop public policies based on evidence-based medicine and on the needs perceived by the population.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Pediatrics

Country/Territory of origin: Colombia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Spera AM, Italy S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhao YQ

| 1. | Estrada-Restrepo A, Restrepo-Mesa SL, Feria ND, Santander FM. [Maternal factors associated with birth weight in term infants, Colombia, 2002-2011]. Cad Saude Publica. 2016;32:e00133215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lizarazo JP, Támara JA, Hoyos LK, López VA, Saraviad GA. Characterization of the causes of mother-child exclusive breastfeeding practice abandonment among women of the kangaroo program in a university hospital. Repert Med y cirugía. 2023;1-6. |

| 3. | Mahecha-Reyes E, Grillo-Ardila CF. Maternal Factors Associated with Low Birth Weight in Term Neonates: A Case-controlled Study. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2018;40:444-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Crump C. Preterm birth and mortality in adulthood: a systematic review. J Perinatol. 2020;40:833-843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dyson L, Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, McCormick F, Herbert G, Thomas J. Policy and public health recommendations to promote the initiation and duration of breast-feeding in developed country settings. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13:137-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cohen SS, Alexander DD, Krebs NF, Young BE, Cabana MD, Erdmann P, Hays NP, Bezold CP, Levin-Sparenberg E, Turini M, Saavedra JM. Factors Associated with Breastfeeding Initiation and Continuation: A Meta-Analysis. J Pediatr. 2018;203:190-196.e21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 36.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sharma IK, Byrne A. Early initiation of breastfeeding: a systematic literature review of factors and barriers in South Asia. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hernández-Vásquez A, Chacón-Torrico H. Determinants of early initiation of breastfeeding in Peru: analysis of the 2018 Demographic and Family Health Survey. Epidemiol Health. 2019;41:e2019051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lutter CK, Chaparro CM, Grummer-Strawn LM. Increases in breastfeeding in Latin America and the Caribbean: an analysis of equity. Health Policy Plan. 2011;26:257-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ardiç C, Yavuz E. Effect of breastfeeding on common pediatric infections: a 5-year prospective cohort study. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2018;116:126-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Aceti A, Beghetti I, Maggio L, Martini S, Faldella G, Corvaglia L. Filling the Gaps: Current Research Directions for a Rational Use of Probiotics in Preterm Infants. Nutrients. 2018;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. The matrix of social inequality in Latin America. Oct 27, 2016. [cited 3 February 2024]. Available from: https://repositorio.cepal.org/items/bbf08250-1bd0-4454-9108-2b8441329f4d. |

| 13. | Arksey H, Malley LO. Scoping studies : towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19-32. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MDJ, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S, Akl EA, Chang C, McGowan J, Stewart L, Hartling L, Aldcroft A, Wilson MG, Garritty C, Lewin S, Godfrey CM, Macdonald MT, Langlois EV, Soares-Weiser K, Moriarty J, Clifford T, Tunçalp Ö, Straus SE. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22118] [Cited by in RCA: 18499] [Article Influence: 2642.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Mújica ÓJ, Moreno CM. [From words to action: measuring health inequalities to "leave no one behind"Da retórica à ação: mensurar as desigualdades em saúde para não deixar ninguém atrás]. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2019;43:e12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Angel COM, Victoria BGM. Evaluación de la autoeficacia en niños y adolescentes. Psicothema. 2002;14:323-332. |

| 17. | Ortelan N, Venancio SI, Benicio MHD. [Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in low birthweight infants under six months of age]. Cad Saude Publica. 2019;35:e00124618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ortelan N, Neri DA, Benicio MHD. Feeding practices of low birth weight Brazilian infants and associated factors. Rev Saude Publica. 2020;54:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wormald F, Tapia JL, Domínguez A, Cánepa P, Miranda Á, Torres G, Rodríguez D, Acha L, Fonseca R, Ovalle N, Anchorena ML, Danner M; NEOCOSUR Network. Breast milk production and emotional state in mothers of very low birth weight infants. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2021;119:162-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ortiz Romaní KJ, Loayza Alarico MJ. Factors associated with early initiation of breastfeeding among Peruvian women. Index enfermería Digit. 2023;32:e14267. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Javela Rugeles JD, Ospino Bermúdez CE, Javela Perez L. Growth of the premature newborn during his first year of life in kangaroo mother program. Pediatria. 2019;52:24-30. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Mangialavori GL, Tenisi M, Fariña D, Abeyá Gilardon EO, Elorriaga N. Prevalence of breastfeeding in the public health sector of Argentina according to the National Survey on Breastfeeding of 2017. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2022;120:152-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Agudelo SI, Gamboa OA, Acuña E, Aguirre L, Bastidas S, Guijarro J, Jaller M, Valderrama M, Padrón ML, Gualdrón N, Obando E, Rodríguez F, Buitrago L. Randomized clinical trial of the effect of the onset time of skin-to-skin contact at birth, immediate compared to early, on the duration of breastfeeding in full term newborns. Int Breastfeed J. 2021;16:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Montoya DIG, Herrera FEL, Jaramillo AMQ, Gómez AA, Cano SMS, Restrepo DA. Breastfeeding abandonment causes and success factors in relactation. Aquichan. 2020;20:1-10. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Charpak N, Montealegre-Pomar A. Follow-up of Kangaroo Mother Care programmes in the last 28 years: results from a cohort of 57 154 low-birth-weight infants in Colombia. BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sequeiros GT, Velazco Cañari MA, Calizaya NR, Medina Vicente LA, Flores CR, Ramírez FV, Afaray JM. Factors associated with the interruption of exclusive breastfeeding: cross-sectional analysis of a Peruvian national survey. Acta Pediatr Mex. 2023;44:263-275. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Aquino M del CO, Rivera RAL, Morales MSLB, Hernández NG, Vera JGL. Knowledge and factors to stop breastfeeding in women of a community in Veracruz, Mexico. Horiz Sanit. 2019;18:195-200. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Spyrakou E, Magriplis E, Benetou V, Zampelas A. Factors Associated with Breastfeeding Initiation and Duration in Greece: Data from the Hellenic National Nutrition and Health Survey. Children (Basel). 2022;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Castillo M, Canales J, Alpízar M, Moreira R. Factors that influence the duration of breastfeeding in university students. Enfermería actual en Costa Rica. 2019;18:1-5. |

| 30. | Araya P, Lopez-Alegria F. Effective interventions to increase the duration and exclusivity of breastfeeding: A systematic review. Rev Chil Obstet Ginecol. 2022;87:26-39. |

| 31. | Piro SS, Ahmed HM. Impacts of antenatal nursing interventions on mothers' breastfeeding self-efficacy: an experimental study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hernández Magdariaga A, Hierrezuelo Rojas N, Gonzáles Brizuela CM, Gómez Soler U, Fernández Arias L. Knowledge level of parents on exclusive breast feeding. MEDISAN. 2023;27:e4541. |

| 33. | Amaliya S, Kapti RE, Astari AM, Yuliatun L, Azizah N. Improving Knowledge and Self-Efficacy in Caring at Home for Parents with Low Birth Weight Babies. J Aisyah J Ilmu Kesehat. 2023;8:819-826. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 34. | Balaguer-Martínez JV, García-Pérez R, Gallego-Iborra A, Sánchez-Almeida E, Sánchez-Díaz MD, Ciriza-Barea E; Red de Investigación en Pediatría de Atención Primaria (PAPenRed). [Predictive capacity for breastfeeding and determination of the best cut-off point for the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale-short form]. An Pediatr (Engl Ed). 2021;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |