Published online Aug 20, 2014. doi: 10.5321/wjs.v3.i3.25

Revised: June 12, 2014

Accepted: July 17, 2014

Published online: August 20, 2014

Processing time: 111 Days and 17.3 Hours

We report the case of 27-year-old female patient applied to our clinic with several pain at her upper teeth and weakness complaints. Anamnesis revealed that she experienced laser gingivectomy to have remarkable teeth. Clinical examination showed that maxillar alveolar bone was partially uncovered with gingivae and periosteum. Interproximal necrosed area was observed. She had sensitivity at her maxillar anterior teeth. Furthermore, she was so anxious and depressed. In order to ensure more blood supply and clot formation, perforations on uncovered cortical bone was prepared. Avoiding from infection antibiotic, antiseptic gel and for epithelization vitamin E gel were prescribed. During one month she was recalled every third day. Recall times diminished periodically, as new tissue evolves. Although laser’s irreversible photothermal effects on soft and hard tissue, after a year all denuded areas were covered with healthy tissues without any surgical procedures. Histopathologic comparing showed severe lymphocyte infiltration and increased fibrosis and kollagenization in restored gingiva, additionally epithelial loss was observed. Since there is not a case report about the complications of laser gingivectomy in literature, we tried to represent a treatment plan that may be elucidative for clinicians.

Core tip: A female patient who was exposed to an improper laser gingivectomy had serious soft and hard tissue loss. Maxillar alveolar bone was partially uncovered with gingiva and periosteum. Moreover necrosed area was observed on bone. Although high heat released during laser application caused several irreversible tissue loss, non-surgical treatment we established resulted in satisfactory aesthetic and functional gains.

- Citation: Kermen E, Orbak R, Calik M, Eminoglu DO. Tissue restoration after improper laser gingivectomy: A case report. World J Stomatol 2014; 3(3): 25-29

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6263/full/v3/i3/25.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5321/wjs.v3.i3.25

Physical attractiveness is an important issue in social life so people effort much for this and face has a key role in it. Several authors reported that face is the most important factor which determines the aesthetic perception of the person[1-4].

Within the face mouth carries nearly 31% importance in the hierarchy of factors in attractiveness judgement[5]. Research has demonstrated that a patient’s smile is a vital component of a beautiful face and it can influence his or her perceived beauty[6,7].

While aesthetic is a great expectance, dentists play an important role in this field. For a perfect smile, harmony between tooth structure and soft tissue is essential, so dentists have to offer acceptable gingival aesthetics, as well as dealing with biological and functional problems. Therefore a variety of means and techniques are used for this purpose such as “crown lengthening”. Crown lengthening surgery is performed for functional and aesthetic purposes. Its major application field for aesthetic enhancement is excessive gingival display. Additionally, it can be performed for gingival enlargement/overgrowth, short clinical crowns, altered passive eruption, vertical maxillar excess, short upper lip or combinations of these conditions[8]. Gingivectomy, gingivoplasty or apically positioned flap which may include osseous resection are the techniques for crown lengthening[9]. Gingivectomy can be performed by scalpel, an electrosurge, a radiosurge or a laser[8,10].

Lasers have been used widely since the beginning of the 1980s in dentistry. Today, due to its many advantages[11-13], it is popular among patients and clinicians. It shows effect via its photothermal feature. For a laser to show biological effect, the energy must be absorbed by tissues. The degree of absorption in tissue will vary as a function of the wavelength and optical characteristics of the target tissue[10]. The absorbed light energy is converted to heat and constitutes a photothermal event. Depending on various parameters, the absorbed energy can result in simple warming, coagulation, or excision and incision through tissue vaporization[14].

It is reported that when bone exposures to heating at levels > 47 °C, cellular damage which leads to osseous resorption occurs and when temperature level reaches to 60 °C, it results with protein denaturation and soft tissue becomes white and over this heat it gets necrosis. At 70 °C soft tissue edges can seethe and at 100 °C evaporation occures, solid and liquid components evaporates[15]. Severe collateral damage is responsible for delayed healing of laser induced bone incisions. Studies report that delayed healing occures at the presence of carbonized layer on the laser treated area and the presence of inert bone fragments encapsulated by fibrous connective tissue, sequestra of bone and bone fragments surrounded by multinucleated giant cells[16,17].

The purpose of this case report is to establish a treatment plan in a female patient who exposed to an improper laser application. Restoring soft and hard tissue is quite difficult surgically or nonsurgically because of high heat released during laser application. When it results in undesired loss of solid and liquid components of the tissue, it gets more difficult but in our case, satisfactory soft and hard tissue restoring was observed without any surgical procedure. Histologically, healing was with collagenization and fibrosis.

A 27-year-old female patient was referred to Ataturk University, Faculty of Dentistry, Periodontology Department with several pain, tooth sensitivity, weakness and a great fear of teeth loss. She was also so anxious about her mouth’s prognosis and depressed because she had a wedding ceremony after a month. She reported that after watching a television programme about gingival aesthetic, she had applied to a dentist for marked and longer teeth. She also said that she’d had a laser gingivectomy 15 d ago before coming to our department. In her dental examination maxillar alveolar bone from right 1st premolar to left 1st premolar was partially uncovered with gingivae and periosteum (Figure 1A-C), moreover, the interproximal bone between right canine and 1st premolar was necrosed (Figure 1B). She had sensitivity at her maxillar anterior teeth. Her left central was sensitive to percusion and colour change was observed (Figure 1A-C).

Perforations on uncovered cortical bone was prepared for opening the marrow spaces to provide more blood supply and clot formation with anesthesia (Ultracaine D-S forte Ampul, Aventis) (Figure 1D).

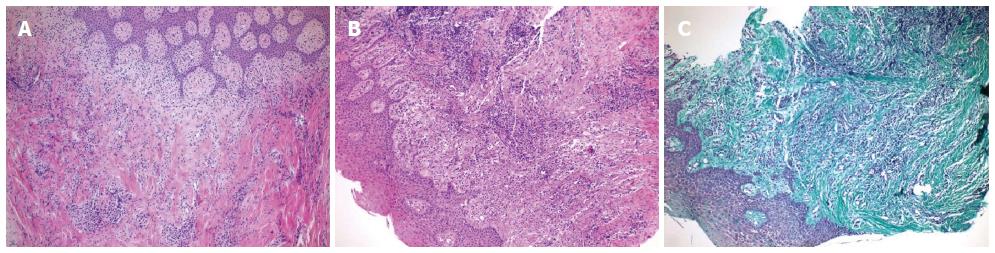

After that prepared area was covered with Peripac® (paste 40 gr, 1.4 oz, Dentsplay) for clot remaining. Flagyl® (500 mg metronidazole, Eczacıbaşı) 3 × 1 a day and Apranax Fort® (550 mg Naproxen Sodium,Abdi İbrahim) were prescribed to patient. But the patient had nausea and diarrhea so we changed the antibiotic and prescribed Augmentin® BID 1000 mg (875 mg Amoxicillin,125 mg clavulanic acid, GlaxoSmith Kline) 2 × 1 a day for 3 wk. The patient was recalled 3 d later for pack removal. Area was irrigated with saline and Elugel (40 mL, 0.20% chlorhexidine, Biocodex) was prescribed 3 × 1 a day for two weeks. Then vit E gel (5 mL, Smartbleach) was prescribed 2 × 1 a day for six months. During one month she was recalled every third day. Recall times diminished periodically, as new tissue evolves. After a month, interdental papillae started to reform, moreover, epithel from the wound edges started to expand and immature epithel was red. Three months later a large amount of exposed alveolar bone was recovered with epithelium (Figure 2). After the new epithel formation, uncovered small bone sequestered came away. About nine months later, all denuded areas were completely recovered with epithelium. According to sensitivity complaint about her left upper central to thermal reactions, vitality test was performed and the tooth was positive. Bifoluride 12 (4 g Bifluoride 12 and 10 mL Solvent, Voco) was applied and the complaints diminished. After a year, all denuded areas were completely covered with gingivae (Figure 3). To compare healthy and restored tissues, biopsy samples were taken from right premolar and molar attached gingivae region. A sample from restored gingiva and also a one from healthy gingiva were taken. Histopathologic comparing of gingiva samples revealed intense lymphocyte infiltration and mild plasma cell infiltration in restored gingiva (Figure 4A and B).

Moreover, when compared with healthy gingiva increased collagenization, fibrosis and epithelial loss were demonstrated in restored gingiva (Figure 4C).

Crown-lengthening surgery can facilitate aesthetic appearence when properly indicated. Gingivectomy is one of the most common surgical technique in this procedure. It can be performed by variety of means such as scalpel, electrosurge, radiosurge or laser[8,10].

Today lasers are popular among patients and clinicians. Precise cut and coagulation that allow dry surgical field for better visualization, sterilization as it cuts and therefore reduction in bacteremia, minimal postoperetive pain and swelling, less postoperative infection, less wound constraction during healing, less damage to adjacent tissues[11] and increased patient acceptance[12,13] are the pereference reasons. But there are some inconsistencies about wound healing after laser surgery. Fisher et al[18] who compared wound healing histologically following laser and conventional surgery, found that wounds heal more quickly and produce less scar tissue than conventional scalpel surgery. However contrary to this sudy, Goultschin et al[19] indicated that gingival healing was delayed and laser had any substantial advantages vs conventional knife gingivectomy.

Not to encounter with undesirable results it is important to follow manufacturer’s guidelines strictly. If not high heat released during laser application can cause delayed healing and undesired loss of tissue’s solid and liquid components[15].

If remaining tissue isn’t enough, restoring of aesthetic, biologic and functional structures may become very difficult surgically and nonsurgically. In our case a wide amount of gingiva and periost was removed so that bone was partially denuded. Remaining tissue was so unsufficent for any surgical procedure so we tried to restore tissue nonsurgically by making perforations on cortical bone. Perforations were prepared for more blood supply and clot formation. For tissue regeneration clot and its stability is essential. Blood clots which promote tissue healing and regeneration, including bone regeneration are rich in platelets and growth factors[20] so we covered prepared perforation area with periodontal pack.

The periosteum which covers the outer surface of all bones has two layers. While inner layer is responsible for osteoblast differentiation and bone regeneration, outer layer is rich in blood vessels and nerves and composed of collagen fibers and fibroblasts[21]. In default of periosteum, bone nourishment is interrupted and resorption risk increases. In our case periosteum was completely removed on laser applicated regions that complicates restoration. In accordance with this purpose, besides aiming restoration we primarily tried to protect bone from infection and resorption. Above all, when considered more than 750 species inhabit the human oral cavity[22] infection risk of denuded bone and damaged remaining soft tissue requires more attention. It can result in more tissue destruction and bone resorption. In order to protect tissues from infection, we prescribed antibiotic and antiseptic gel until new tissue starts to generates. Additionally, assisting to epithelization vit E was prescribed.

Furthermore, because of denuded bone, open edges of remaining periosteum and inflammation which occured after improper application she had so much pain so we prescribed an anti inflammatuar analgesic.

Our patient was so anxious about her teeth’s prognosis and she was very depressed so either to observe tissue response to treatment or to support patient pshycologically, initially we recalled her every third day. As tissue heals recalling times were reduced.

Although high heat caused irreversible soft and hard tissue loss, a year later all denuded bone was recovered with epithel. Satisfactory aesthetic and functional results were obtained with no need to any surgical procedure and it has almost reverted. Comparative histological examinations demonstrated increased collagenization and fibrosis in restored gingiva. This proved that gingival restoration eventuated with scar tissue formation after improper laser gingivectomy. Additionally, increased chronic inflammatory cells were expressed in restored gingiva. This can be correlated with epithelial loss and healing with scar tissue which can make gingiva more vulnerable to plaque accumulation. We think that this report will be elucidative for clinicians because in literature there is no case which can be compared in terms of therapeutic approaches about an improper laser gingivectomy which resulted in serious tissue loss. Moreover this report proves the importance of true wavelength laser and patient selection besides being educated for laser applications.

A 27-year-old female who was exposed to an improper laser gingivectomy presented with several pain, tooth sensitivity, weakness and a great fear of teeth loss.

From right 1st premolar to left 1st premolar partially denuded maxillar alveolar bone uncovered with gingivae and periosteum, necrosed bone between right canine and 1st premolar, sensitivity at her maxillar anterior teeth and colour change and positive reaction to percussion at her left upper central tooth.

Tissue healing process, osteonecrosis of the jaw, chemical burn.

Histopathologic gingiva samples revealed intense lymphocyte infiltration and mild plasma cell infiltration, increased collagenization, fibrosis and epithelial loss in restored gingiva compared with healthy gingiva.

Perforations on uncovered cortical bone was prepared and the patient was treated with Augmentin® BID 1000 mg (875 mg Amoxicillin,125 mg clavulanic acid), Apranax Fort® (550 mg Naproxen Sodium), Elugel (40 mL, 0.20% chlorhexidine) and vit E gel.

Restoring soft and hard tissue is quite difficult surgically or nonsurgically because of high heat released during laser application and it gets more difficult when it results in undesired loss of solid and liquid components of the tissue.

Crown lengthening is a technique which exposes more of the natural tooth by reshaping or recontouring bone and gum tissue.

This report will be elucidative for clinicians because in literature there is no case which can be compared in terms of therapeutic approaches about an improper laser gingivectomy which resulted in serious tissue loss. Moreover this report proves the importance of true wavelength laser and patient selection besides being educated for laser applications.

It is well-written and interesting case-report. The authors explained all healing process detailly.

P- Reviewer: Mazzocchi M, Muluk NB S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Patzer GL. The Physical Attractiveness Phenomena. New York: Plenum Press 1985; . |

| 2. | Peck S, Peck L. Selected aspects of the art and science of facial esthetics. Semin Orthod. 1995;1:105-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kerns LL, Silveira AM, Kerns DG, Regennitter FJ. Esthetic preference of the frontal and profile views of the same smile. J Esthet Dent. 1997;9:76-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Van der Geld P, Oosterveld P, Van Heck G, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM. Smile attractiveness. Self-perception and influence on personality. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:759-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Goldstein RE. Study of need for esthetics in dentistry. J Prosthet Dent. 1969;21:589-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Flores-Mir C, Silva E, Barriga MI, Lagravere MO, Major PW. Lay person’s perception of smile aesthetics in dental and facial views. J Orthod. 2004;31:204-209; discussion 201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kerosuo H, Hausen H, Laine T, Shaw WC. The influence of incisal malocclusion on the social attractiveness of young adults in Finland. Eur J Orthod. 1995;17:505-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hempton TJ, Dominici JT. Contemporary crown-lengthening therapy: a review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:647-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nethravathy R, Vinoth SK, Thomas AV. Three different surgical techniques of crown lengthening: A comparative study. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2013;5:S14-S16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Research, Science and Therapy Committee of the American Academy of Periodontology. Lasers in periodontics. J Periodontol. 2002;73:1231-1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rossmann JA, Cobb CM. Lasers in periodontal therapy. Periodontol 2000. 1995;9:150-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Wigdor HA, Walsh JT, Featherstone JD, Visuri SR, Fried D, Waldvogel JL. Lasers in dentistry. Lasers Surg Med. 1995;16:103-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 289] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bader HI. Use of lasers in periodontics. Dent Clin North Am. 2000;44:779-791. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Cobb CM. Lasers in periodontics: a review of the literature. J Periodontol. 2006;77:545-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Eriksson AR, Albrektsson T. Temperature threshold levels for heat-induced bone tissue injury: a vital-microscopic study in the rabbit. J Prosthet Dent. 1983;50:101-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 885] [Cited by in RCA: 805] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | McDavid VG, Cobb CM, Rapley JW, Glaros AG, Spencer P. Laser irradiation of bone: III. Long-term healing following treatment by CO2 and Nd: YAG lasers. J Periodontol. 2001;72:174-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Williams TM, Cobb CM, Rapley JW, Killoy WJ. Histologic evaluation of alveolar bone following CO2 laser removal of connective tissue from periodontal defects. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1995;15:497-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fisher SE, Frame JW, Browne RM, Tranter RM. A comparative histological study of wound healing following CO2 laser and conventional surgical excision of canine buccal mucosa. Arch Oral Biol. 1983;28:287-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Goultschin J, Gazit D, Bichacho N, Bab I. Changes in teeth and gingiva of dogs following laser surgery: a block surface light microscope study. Lasers Surg Med. 1988;8:402-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kabashima H, Sakai T, Mizobe K, Nakamuta H, Kurita K, Terada Y. The usefulness of an autologous blood clot combined with gelatin for regeneration of periodontal tissue. J Oral Sci. 2013;55:363-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA. Anatomy of the Periodontium. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Saunders 2012; 12-27. |

| 22. | Ji X, Pushalkar S, Li Y, Glickman R, Fleisher K, Saxena D. Antibiotic effects on bacterial profile in osteonecrosis of the jaw. Oral Dis. 2012;18:85-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |