Published online Mar 28, 2017. doi: 10.5320/wjr.v7.i1.29

Peer-review started: September 9, 2016

First decision: October 20, 2016

Revised: December 1, 2016

Accepted: December 16, 2016

Article in press: December 19, 2016

Published online: March 28, 2017

Processing time: 202 Days and 0 Hours

Synchronous tumors are an uncommon finding. We present a case of metastatic carcinoma of right breast and a left lung adenocarcinoma in a patient with previous history of left breast cancer diagnosed twelve years ago. She was then treated with chemotherapy, radiotherapy and hormone therapy. Initially, the greatest diagnostic challenge was which of them had spread or if both had. Or even if, any of these lesions resulted from the primary left breast cancer. So, specimens of different metastatic lesions were crucial to answer this query and to decide the best therapeutic approach. Sequencing the treatment options in managing two synchronous secondary malignancies, where one of them is metastatic and the other one is potentially curable, was a demanding clinical decision.

Core tip: This case presents a patient with previous left breast cancer in the past that now has a diagnosis of right breast cancer. The staging exams revealed metastatic lesions on bone and left adrenal gland and a suspicious lesion on the left lung. Histology of those lesions allowed us to conclude there were a metastatic breast cancer and a localized lung cancer.

- Citation: de Macedo JE. Synchronous lung and breast cancer. World J Respirol 2017; 7(1): 29-34

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6255/full/v7/i1/29.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5320/wjr.v7.i1.29

Synchronous tumors are defined as distinct tumors arising simultaneously or diagnosed in a range of less than 6 mo apart[1]. The incidence of multiple primary malignancies is 0.73%-11.7%[2,3] and it is believed that the incidence has been increasing due to increased life expectancy and progressive advances in diagnostic techniques. It remains in debate the contribution of genetic, immunological and environmental mechanisms[4]. In this clinical case, there is an increased risk of second malignancies related to previous breast cancer history and respective treatments performed.

A 43-year-old non-smoker women, asymptomatic, with a previous history of cancer on the left breast diagnosed and treated in 2003. The patient was treated with left modified radical mastectomy, adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil 780 mg, epirubicin 117 mg and cyclophosphamide 780 mg, 21-21 d for six cycles. Adjuvant radiotherapy was performed (50Gy left chest wall, supraclavicular region at 50 Gy and 45 Gy in internal mammary lymph node chain). Hormone therapy with tamoxifen and LHRH analog was delivered for 5 years. After seven years of follow-up, she was referred to her personal physician.

Asymptomatic until June 2015, when she was referenced to our Institution for evaluation of two lumps in her right breast (31 mm nodule in inferior lateral quadrant and another in the transition of the external quadrants with 11 mm) detected in her annual mammography. A palpable right axillary lymph node, painless and with a hard consistence was diagnosed on physical examination.

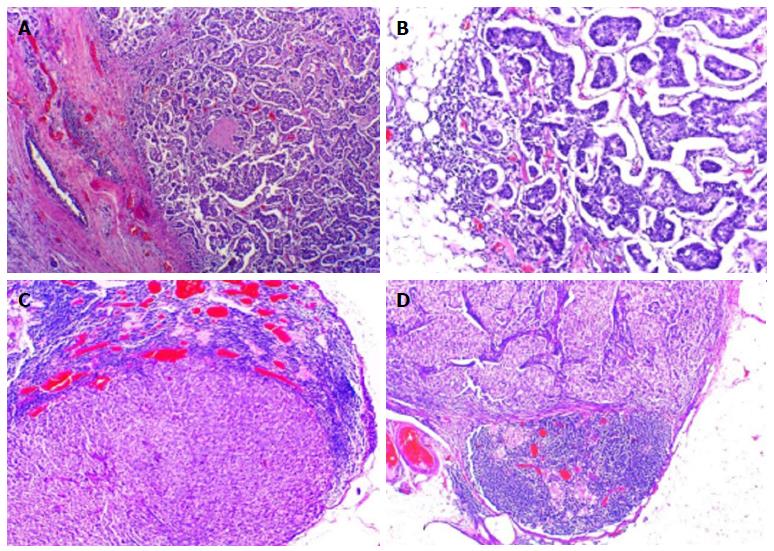

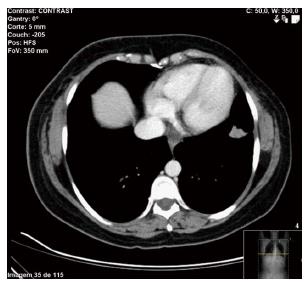

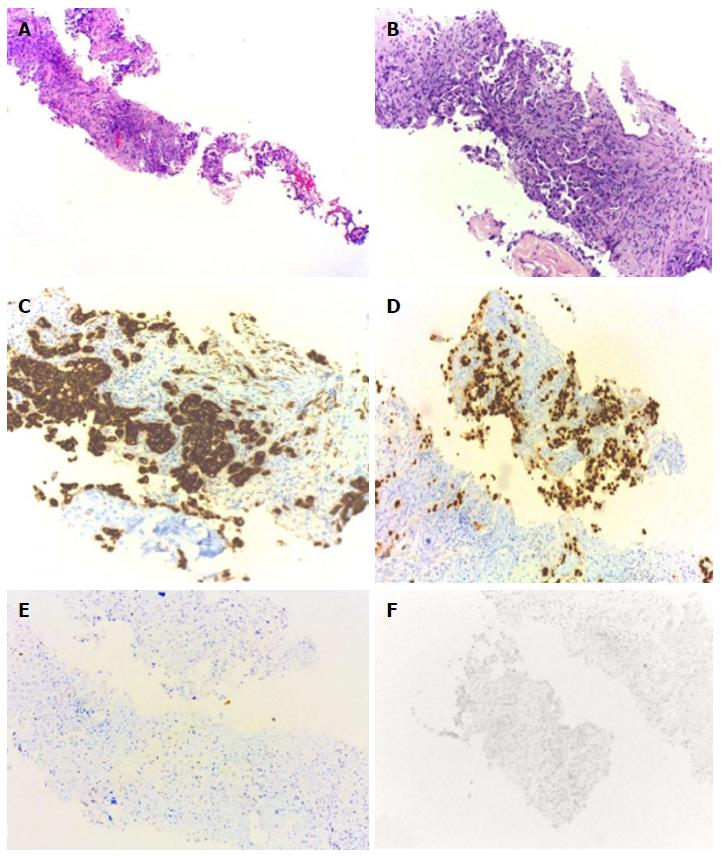

A fine needle aspiration biopsy was performed of the larger breast nodule and the palpable lymphadenopathy revealed an invasive ductal carcinoma of breast, RE 100% PR < 10%, negative HER2, Ki67 60%-75%. The patient underwent a right modified radical mastectomy and axillary lymph node dissection in July of 2015. Histology confirmed a breast carcinoma and showed an extensive metastasis of ipsilateral axillary lymph nodes (21 positive lymph nodes in 25), pT2N2aMx (Figure 1). Thoracic and abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 17 mm suspicious lung nodule in the left lower lobe and two lytic lesions in dorso-lumbar column (Figure 2). The whole spine magnetic resonance imaging confirmed infiltrative lesions of secondary nature in D8, D11, L3 and S1. The biopsy of the lung lesion showed features of moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, positive for CK7 and TTF1 and negative for estrogen receptor, pT1aN0Mx (Figure 3). The positron emission tomography-CT scan showed uptake in the right infra-clavicle and axillary lymph nodes, lump in the basal segment of the lower lobe of the left lung, left adrenal gland and D8, D11, L3 vertebral bodies and left iliac wing.

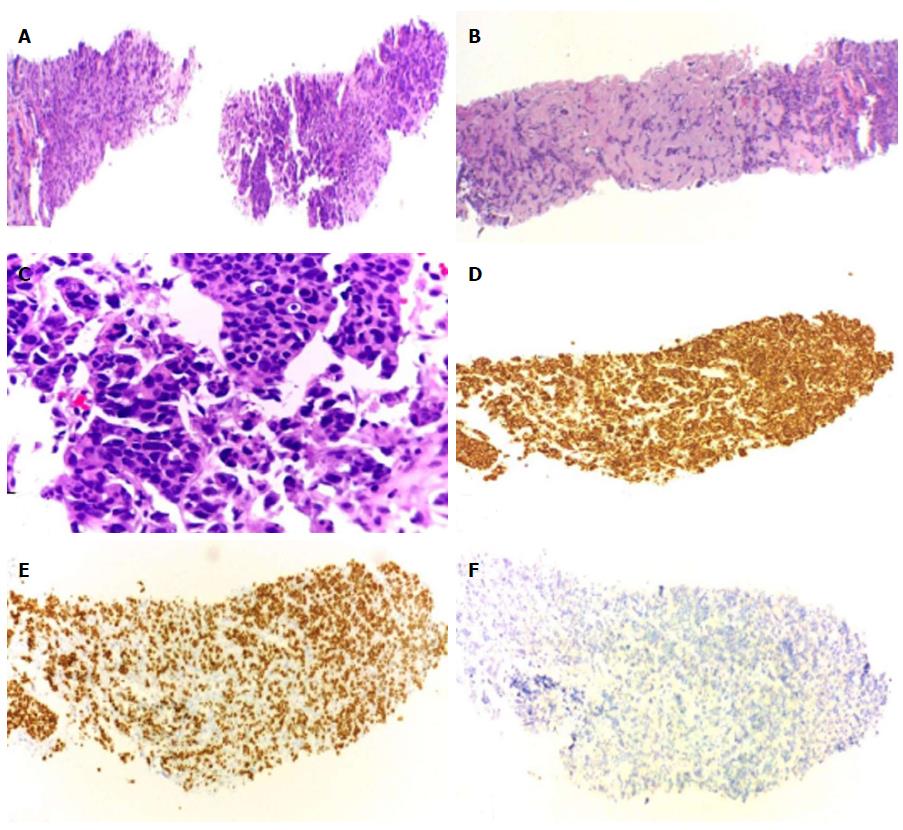

In the presence of synchronous secondary malignancies of the breast and lung with potential for bone and adrenal metastases, it was necessary to clarify the origin of these lesions to guide the best therapeutic approach. So, the patient underwent bone and adrenal gland biopsies. Both histology’s confirmed metastasis of breast cancer (Figure 4). Palliative chemotherapy was delivered with docetaxel 120 mg and cyclophosphamide 960 mg, every three weeks, for a total of four cycles; zoledronic acid 4 mg iv, every four weeks and calcium and vitamin D supplementation. This particular regimen of chemotherapy now chosen was justified by the cumulative dose of anthracyclines already performed in the past.

Not neglecting a 43-year-old fit woman, imaging re-evaluation after chemotherapy will be performed, to consider radical treatment of lung adenocarcinoma and initiate hormone therapy.

Despite of breast and lung cancers being the most common tumors in females, the diagnosis of synchronous cancer is nevertheless an uncommon finding. Multiple primary malignancies in a single patient were first described in 1870 by Billroth[6]. The increase incidence of multiple primary cancers may be due to long life expectancy, progressive advances in diagnostic techniques, regular follow-up and genetic predisposition to cancer[5]. It remains in debate the contribution of genetic, immunological and environmental mechanisms[4]. In this particular case, previous exposure to chemotherapy and endocrine therapy may have protected the patient form tumor relapse and metachronous breast tumors. On the other hand, a slightly increased risk of lung cancer after radiotherapy for breast cancer, on the same side, has been previously reported. The current criteria for the diagnosis of multiple primary malignancies, which were established by Warren et al[6], are as follows: First, each of the lesions must be malignant; secondly, each of the lesions must exhibit distinctively different pathologies and thirdly, metastases from the prior malignancies must be excluded. Synchronous carcinomas are defined as those tumors diagnosed either simultaneously or within an interval of six months, after the diagnosis of the first one[1].

A pulmonary left nodule in women with history of left breast cancer could be a metastatic disease, primary lung cancer or a benign lesion. In 55% of the cases, it represents a primary lung cancer and in 37% a metastatic breast cancer[7,8]. The major diagnostic challenge in this case report, is whether which of the cancers (breast carcinoma or adenocarcinoma of the lung) had spread, if both or only one. Secondly, where to: Bone, adrenal gland or both. Nowadays, it is mandatory to perform biopsies of the different metastases and immunohistochemistry staining. Specimen of different metastatic sites is crucial in order to discriminate the oncogenic pathway of proliferation, and define the primary origin of those secondary lesions.

Nowadays, intraoperative frozen sections make false-positive diagnosis that mistakes benign for malignant, but there are 1.1% to 4.0% of false-negative diagnoses[9]. However, in this case report multiple frozen biopsies could have been performed, if possible, at same surgical timing in different locations (bone, left adrenal gland and left lung nodule biopsy). Nevertheless, nowadays liquid biopsies and circulating free DNA are gaining evidence with statistical sensitivity and sensibility in a non-invasive and less expensive procedure, with a more accurate molecular characterization[10].

The treatment of such cases depends on the individual primary location, tumor’s aggressiveness, staging, genetic profile, co-morbidities, performance status and toxicities of previous treatments performed. All of these details should be discussed in a multidisciplinary team, with the patient’s medical oncologist and most importantly, with the patient in order to preserve his quality of life.

This case illustrates the challenge in the diagnosis and characterization of metastatic lesions, but also, the difficulty in managing two synchronous secondary malignancies, where one of them is metastatic and the other one is potentially curable.

A 43-year-old non-smoker women, asymptomatic, with a previous history of cancer on the left breast, presented with two lumps in her right breast in an annual mammography, and a painless, with a hard consistence, palpable right axillary lymph node on her physical examination.

Two metachronous cancers: A right breast cancers and a left lung nodule.

Diagnostic challenge in this case report, is whether which of the cancers (right breast carcinoma or adenocarcinoma of the left lung) had spread, if both or only one, and secondly, where to: Bone, adrenal gland or both. A third option is if any of the metastases could even be result from dissemination of the left breast tumor twelve years ago.

Perform biopsies of the different metastases and immunohistochemistry staining is mandatory.

Thoracic and abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan, spine magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography-fluorodeoxyglucose CT scan is essential to evaluate the extent of the disease and its characterization.

Specimen of different metastatic sites is crucial in order to discriminate the primary origin of those secondary lesions.

The treatment of such cases depends on the individual primary location, tumor’s aggressiveness, staging, genetic profile, co-morbidities, performance status and toxicities of previous treatments performed, namely accumulated dose from the anthracyclines performed earlier.

A pulmonary left nodule in women with history of left breast cancer could be a metastatic disease, primary lung cancer or a benign lesion. In 55% of the cases, it represents a primary lung cancer and in 37% a metastatic breast cancer.

Further molecular profiling for selecting the specific target therapy, is of upmost importance for defining the molecular signature of these tumors.

Tumor characterization by clinical, imagological and histological means is still vital, but molecular profiling will allow us to treat the patients more efficiently, with better quality of life and lower toxicity profile.

This case report based on the reality of practice will draw attention from wide-ranged repirology specialist. It is a very attractive topic.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Respiratory system

Country of origin: Portugal

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P- Reviewer: Sugimura H, Tsikouras PPT, Zafrakas M S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Moertel CG, Dockerty MB, Baggenstoss AH. Multiple primary malignant neoplasms. II. Tumors of different tissues or organs. Cancer. 1961;14:231-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Demandante CG, Troyer DA, Miles TP. Multiple primary malignant neoplasms: case report and a comprehensive review of the literature. Am J Clin Oncol. 2003;26:79-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kurul S, Akgun Z, Saglam EK, Basaran M, Yucel S, Tuzlali S. Successful treatment of triple primary tumor. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:1013-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Abeloff MD, Armitage JO, Niederhuber JE, Kastan MB, McKenna WG. Abeloff’s Clinical Oncology. New York: Churchill Livingstone 2008; 1023-1037. |

| 5. | Soerjomataram I, Coebergh JW. Epidemiology of multiple primary cancers. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;471:85-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Warren S, Gates O. Multiple primary malignant tumors: A survey of the literature and statistical study. Am J Cancer. 1932;16:1358-1414. |

| 7. | Burstein HJ, Swanson SJ, Christian RL, McMenamin ME. Unusual aspects of breast cancer: case 2. Synchronous bilateral lung and breast cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2571-2573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Casey JJ, Stempel BG, Scanlon EF, Fry WA. The solitary pulmonary nodule in the patient with breast cancer. Surgery. 1984;96:801-805. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Yamashita T, Funai K, Kawase A, Mori H, Baba S, Shiiya N, Sugimura H. A quick-frozen section diagnosis of a lung tumor in a patient with a gastric cancer history. Case Reports in Clinical Pathology. 2015;2. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, Kinde I, Wang Y, Agrawal N, Bartlett BR, Wang H, Luber B, Alani RM. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:224ra24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2770] [Cited by in RCA: 3527] [Article Influence: 320.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |