Published online Jun 17, 2025. doi: 10.5320/wjr.v14.i1.109353

Revised: May 14, 2025

Accepted: May 28, 2025

Published online: June 17, 2025

Processing time: 40 Days and 10.6 Hours

Exogenous lipoid pneumonia is a rare and under recognized pulmonary disorder caused by the inhalation or aspiration of fat-like substances. Nasal decongestants containing mineral oils or paraffin are emerging as overlooked etiological agents. This review consolidates existing literature to delineate the clinical, radiological, and pathological features of exogenous lipoid pneumonia induced by nasal decongestants, highlight diagnostic challenges, and underscore the importance of thorough patient history in early diagnosis and management. This condition, while preventable, can result in serious pulmonary complications if not recog

Core Tip: Exogenous lipoid pneumonia from nasal decongestants is a preventable but often missed diagnosis. Early recognition through detailed history and imaging is crucial to avoid serious lung complications.

- Citation: Basit A, Kiran T, Shaista F, Saifullah M, Basil AM. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia associated with nasal decongestants use: A narrative review of an under recognized clinical entity. World J Respirol 2025; 14(1): 109353

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6255/full/v14/i1/109353.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5320/wjr.v14.i1.109353

Lipoid pneumonia is classified as exogenous or endogenous, depending on the source of lipid accumulation. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia (ELP) arises from inhalation or aspiration of fat-containing substances, commonly found in nasal or oral therapeutic agents. The increasing use of over-the-counter nasal sprays and drops, especially those with mineral oils, has led to a rise in ELP cases. However, its nonspecific symptoms and radiologic similarities to other lung diseases contribute to underdiagnosis. Osman et al[1] were among the first to link ELP to chronic nasal decongestant use, reporting findings from ground-glass opacities to mass-like lesions confirmed by bronchoalveolar lavage and electron microscopy[1,2]. ELP is often mistaken for malignancy or atypical pneumonia, highlighting the need for thorough history-taking and differential diagnosis[3,4]. Once considered rare, improved imaging and reporting suggest ELP is more prevalent, particularly in the elderly and those with chronic sinonasal conditions. In children, accidental administration of oily substances like cod liver oil or traditional remedies also contributes to ELP, underscoring the need for awareness across all age groups[5,6].

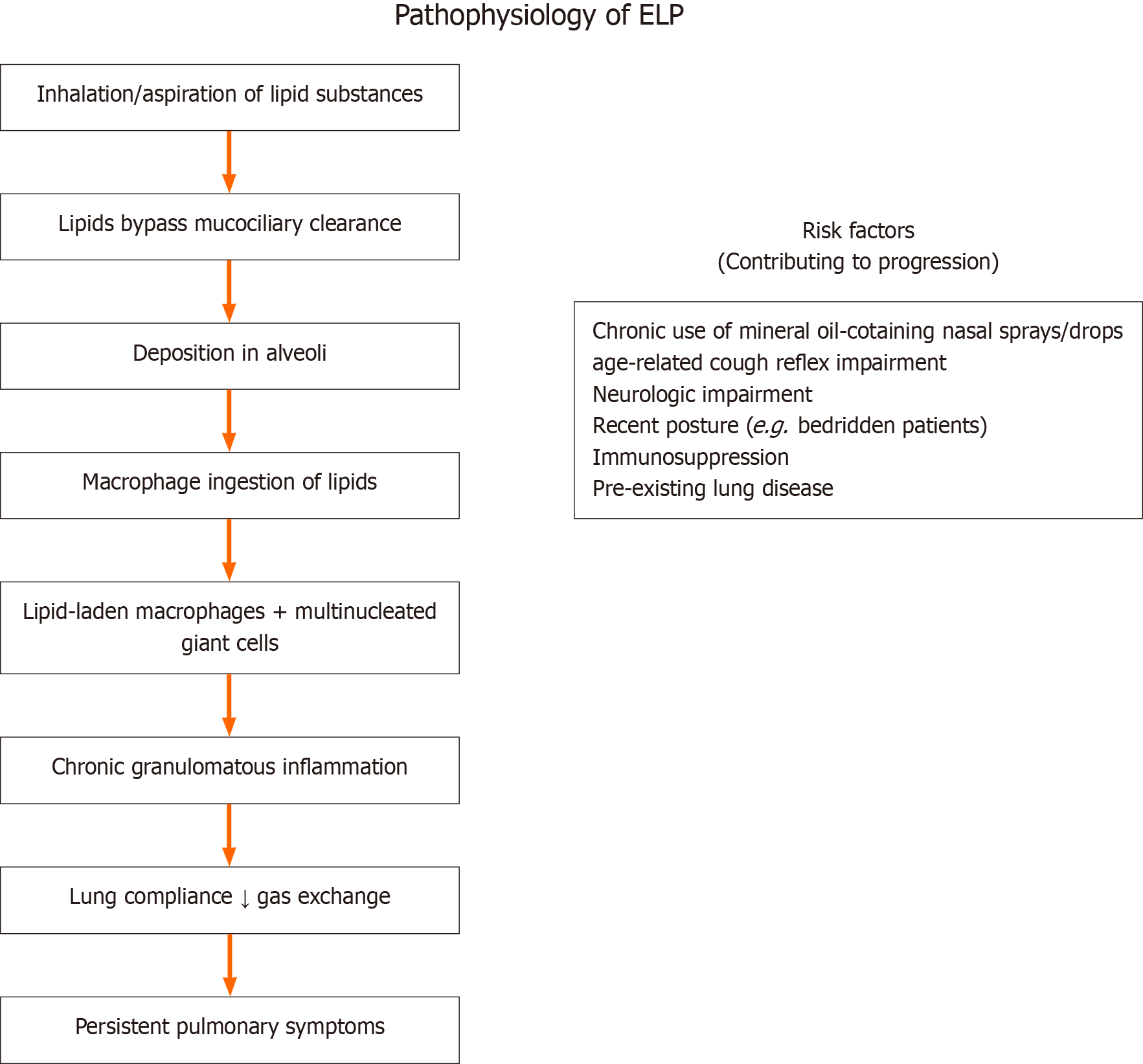

The pathogenesis of ELP involves the inhalation of lipid substances, which bypass mucociliary clearance and deposit in alveoli. These substances resist enzymatic degradation, resulting in macrophage ingestion, granulomatous inflammation, and potentially fibrosis. Once in the alveolar space, mineral oils initiate a chronic inflammatory response that can evolve into a fibrotic process if left untreated[8].

Histologically, the presence of lipid-laden macrophages, multinucleated giant cells, and chronic interstitial inflammation with lipid vacuoles is characteristic. Chronic lipid deposition causes fibrosis, impairing lung compliance and gas exchange. The risk increases with chronic use of nasal formulations containing mineral oil, liquid paraffin, or petrolatum. Lu et al[3] highlighted the case of a patient with chronic rhinitis who self-administered mentholated oil nasal drops over a decade, eventually developing persistent pulmonary symptoms that led to an ELP diagnosis after transbronchial lung biopsy.

Other risk factors include age-related decline in the cough reflex, neurologic impairment, and recumbence which can exacerbate aspiration risks. Immunocompromised individuals or those with pre-existing pulmonary conditions are also at higher risk for more severe disease progression[9]. Figure 1 shows the pathophysiology of ELP.

ELP may be asymptomatic or present with cough, dyspnea, fever, or chest pain, often mimicking infectious pneumonia or malignancy. The onset may be insidious, with symptoms developing over weeks to months. In Kilaru et al’s report[4], a patient using petrolatum ointment for nasal decongestion developed symptomatic ELP successfully treated with corticosteroids.

Radiologically, ELP is characterized by ground-glass opacities, consolidations, or a “crazy paving” pattern, all of which can lead to diagnostic confusion. HRCT is indispensable for detecting these changes, especially in patients with a chronic cough and unclear imaging findings. Specific radiologic clues include low attenuation within consolidations and preservation of lobular architecture[10].

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) often reveals lipid-laden macrophages, while lung biopsy confirms histological features such as vacuolated macrophages and lipid granulomas. In asymptomatic or indeterminate cases, BAL cytology combined with special stains like Oil Red O or Sudan IV greatly improves diagnostic certainty[11].

Schoofs et al[5] presented a case initially mistaken for medication-induced eosinophilic pneumonia, later diagnosed as ELP following detailed anamnesis revealing chronic use of paraffin nasal drops. Additional supportive tools include pulmonary function tests, which often reveal a restrictive pattern with reduced diffusion capacity, especially in chronic or fibrotic stages.

Table 1 compares exogenous vs endogenous lipoid pneumonia. The primary diagnostic challenge lies in distinguishing ELP from more common pulmonary diseases. It may be mistaken for bacterial pneumonia due to fever and infiltrates or for malignancy when presenting as a solitary pulmonary nodule. Radiologic overlap with interstitial lung disease further complicates the picture. A comprehensive history, particularly regarding long-term nasal decongestant use, is essential.

| Feature | Exogenous Lipoid Pneumonia | Endogenous Lipoid Pneumonia |

| Etiology | Inhalation or aspiration of exogenous lipid substances (e.g., nasal oils, mineral oil) | Lipid accumulation from cell breakdown due to bronchial obstruction (e.g., tumors, infections) |

| Common risk groups | Elderly, children, chronic users of oil-based nasal sprays | Patients with obstructive pulmonary diseases or malignancies |

| Onset | Often insidious, related to exposure history | Secondary to underlying lung pathology |

| Radiological findings | Ground-glass opacities, consolidations, low-attenuation areas | Cholesterol clefts, mass-like lesions, variable opacities |

| Histological features | Lipid-laden macrophages, lipid vacuoles, granulomas | Cholesterol crystals, foamy macrophages, associated necrosis |

| BAL findings | Numerous lipid-laden macrophages (positive on Oil Red O stain) | Foamy macrophages may be present, but lipid content endogenous |

| Management | Discontinue exposure; corticosteroids in severe cases | Treat underlying cause (e.g., tumor, obstruction); supportive care |

| Prognosis | Generally favorable if caught early | Depends on resolution of underlying pathology |

The diagnostic triad consists of imaging suggestive of ELP, history of oil exposure, and cytological confirmation via BAL or biopsy. Misdiagnosis can lead to prolonged antibiotic use or unwarranted invasive procedures. Furthermore, in cases without overt lipid exposure, clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion and probe for alternative sources like herbal remedies or home-based oil therapies[12].

In children and elderly patients, differential diagnoses may include aspiration pneumonia, pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, or bronchiectasis. It is also essential to distinguish ELP from endogenous lipoid pneumonia, which arises from lipid accumulation secondary to cellular breakdown due to bronchial obstruction[6].

The cornerstone of treatment is the immediate cessation of the offending agent. Symptomatic patients may benefit from corticosteroids to reduce inflammation. Kilaru et al[4] documented improvement with prednisolone, while other reports suggest spontaneous resolution after exposure discontinuation.

In some cases, therapeutic BAL has been used to mechanically remove lipid material from alveoli, leading to clinical and radiological improvement[9]. Antibiotics are not typically indicated unless a secondary bacterial infection is present. For severe or progressive cases, especially those with hypoxemia or fibrosis, corticosteroids and supportive therapy such as oxygen supplementation are warranted.

Long-term outcomes are generally favorable if ELP is diagnosed early. However, chronic cases may result in pulmonary fibrosis or persistent radiographic abnormalities. Pulmonary function tests may show restrictive changes or decreased diffusion capacity in such scenarios[10]. Follow-up imaging and lung function monitoring are advised. Preventive strategies should include clinician education and patient awareness regarding the risks of chronic oil-based nasal spray use[9,10].

Despite increasing reports, ELP remains poorly recognized. Underreporting and misdiagnosis contribute to its elusive epidemiology. Raising awareness among clinicians about the condition, ensuring thorough history-taking, and educating patients on the risks associated with oil-based nasal preparations are vital steps. Regulatory bodies should consider warnings on packaging and restrict the unregulated use of such products[6,8].

Community health outreach programs should emphasize the dangers of chronic self-medication with oil-based nasal products. Educational campaigns targeting pharmacists and general practitioners can help prevent unnecessary prescriptions[9]. Moreover, ELP should be included in the differential diagnosis for patients presenting with unexplained pulmonary infiltrates, particularly when initial treatment fails[9,11].

Future studies should aim at estimating prevalence and establishing standardized diagnostic criteria. Public health messaging can also incorporate information on safer alternatives to mineral oil-based products, particularly in pediatric and elderly populations. Implementing product labeling regulations that clearly warn about potential inhalation hazards may also reduce incidence.

ELP due to nasal decongestants is a preventable and often reversible condition that mimics other serious pulmonary diseases. A high index of suspicion, supported by clinical history and confirmatory tests, can prevent unnecessary interventions and ensure timely management. As the use of topical nasal agents continues, awareness and vigilance remain key to reducing the burden of this under recognized disease.

Multidisciplinary collaboration between pulmonologists, radiologists, pathologists, and primary care providers is essential to enhance early recognition and treatment. Preventive strategies must extend beyond clinical settings to include community awareness and regulatory oversight.

| 1. | Osman GA, Ricci A, Terzo F, Falasca C, Giovagnoli MR, Bruno P, Vecchione A, Raffa S, Valente S, Torrisi MR, De Dominicis C, Giovagnoli S, Mariotta S. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia induced by nasal decongestant. Clin Respir J. 2018;12:524-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bartosiewicz M, Zimna K, Lewandowska K, Sobiecka M, Dybowska M, Radwan-Rohrenschef P, Szturmowicz M, Tomkowski W. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia induced by nasal instillation of paraffin oil. Adv Respir Med. 2019;87:254-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bandla HP, Davis SH, Hopkins NE. Lipoid pneumonia: a silent complication of mineral oil aspiration. Pediatrics. 1999;103:E19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gondouin A, Manzoni P, Ranfaing E, Brun J, Cadranel J, Sadoun D, Cordier JF, Depierre A, Dalphin JC. Exogenous lipid pneumonia: a retrospective multicentre study of 44 cases in France. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:1463-1469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schoofs C, Bladt L, De Wever W. An uncommon cause of asymptomatic crazy paving pattern. J Belg Soc Radiol. 2010;93:228. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lu M, Yan W, Zhu X, Zhu H. [Exogenous lipoid pneumonia induced by long-term usage of compound menthol nasal drops: a case report]. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2019;51:359-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kilaru H, Prasad S, Radha S, Nallagonda R, Kilaru SC, Nandury EC. Nasal application of petrolatum ointment - A silent cause of exogenous lipoid pneumonia: Successfully treated with prednisolone. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;22:98-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hadda V, Khilnani GC. Lipoid pneumonia: an overview. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2010;4:799-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Marchiori E, Zanetti G, Mano CM, Irion KL, Daltro PA, Hochhegger B. Lipoid pneumonia in 53 patients after aspiration of mineral oil: comparison of high-resolution computed tomography findings in adults and children. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2010;34:9-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Betancourt SL, Martinez-Jimenez S, Rossi SE, Truong MT, Carrillo J, Erasmus JJ. Lipoid pneumonia: spectrum of clinical and radiologic manifestations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:103-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yeung SHM, Rotin LE, Singh K, Wu R, Stanbrook MB. Exogenous lipoid pneumonia associated with oil-based oral and nasal products. CMAJ. 2021;193:E1568-E1571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Braggio C, Bocchialini G, Ventura L, Carbognani P, Tiseo M, Gnetti L, Rusca M, AmpolliniL. EP1.09-11. Lipoid Pneumonia Resembling Bilateral Lung Cancer: Be Aware of Nasal Decongestants! J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14:S1002. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |