Published online Nov 27, 2015. doi: 10.5313/wja.v4.i3.49

Peer-review started: May 7, 2015

First decision: July 30, 2015

Revised: September 2, 2015

Accepted: September 10, 2015

Article in press: September 16, 2015

Published online: November 27, 2015

Processing time: 209 Days and 20.5 Hours

The zygapophysial joints (z-joints), together with the intervertebral disc, form a functional spine unit. The joints are typical synovial joints with an innervation from two medial branches of the dorsal rami. The joint capsule and the surrounding structures have an extensive nerve supply. The stretching of the capsule and loads being transmitted through the joint can cause pain. The importance of the z-joints as a pain generator is often underestimated because the prevalence of z-joint pain (10%-80%) is difficult to specify. Z-joint pain is a somatic referred pain. Morning stiffness and pain when moving from a sitting to a standing position are typical. No historic or physical examination variables exist to identify z-joint pain. Also, radiologic findings do not have a diagnostic value for pain from z-joints. The method with the best acceptance for diagnosing z-joint pain is controlled medial branch blocks (MBBs). They are the most validated of all spinal interventions, although false-positive and false-negative results exist and the degree of pain relief after MBBs remains contentious. The prevalence of z-joint pain increases with age, and it often comes along with other pain sources. Degenerative changes are commonly found. Z-joints are often affected by osteoarthritis and inflammatory processes. Often additional factors including synovial cysts, spondylolisthesis, spinal canal stenosis, and injuries are present. The only truly validated treatment is medial branch neurotomy. The available technique vindicates the use of radiofrequency neurotomy provided that the correct technique is used and patients are selected rigorously using controlled blocks.

Core tip: This review emphasizes the importance of the zygapophysial joints (z-joints) as a pain generator. Taking the historic or the physical examination are not helpful in identifying z-joint pain. The prevalence of z-joint pain increases with age, and it often comes along with other pain sources. The focus is on the significance of z-joint pain in elaborated patient groups in which z-joint pain is clinically relevant but does not occur as an isolated and independent disease. Diagnostic methods and the treatment with radiofrequency neurotomy are discussed.

- Citation: Klessinger S. Zygapophysial joint pain in selected patients. World J Anesthesiol 2015; 4(3): 49-57

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-6182/full/v4/i3/49.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5313/wja.v4.i3.49

The smallest functional motion consists of two vertebrae, all adjoining ligaments between them, and three joints. First, there is the interbody joint, which consists of the intervertebral disc and the vertebral endplates. The other two joints are the paired zygapophysial joints (z-joints), which are formed by the articulation of the inferior and superior articular processes of two adjacent lumbar vertebra. The nomenclature of the small joints of the vertebral spine is inconsistent. Facet joint is commonly used in North American literature to describe paired synovial joints between the posterior elements of adjacent vertebrae. The joints are also known as z-joints, zygapophyseal joints, apophysial joints, or posterior intervertebral joints. Because a facet is simply a small articular surface and, as such, pertains to any small joint, in this review the term z-joint is used.

The existence of pain deriving from the z-joints is discussed controversially. In the existing literature there is no support for the existence of a facet syndrome. There are no typical examination findings or diagnostic proofs to justify the term “syndrome”. Z-joint pain is defined as pain originating from any structure essential to the function and the configuration of the lumbar facet joints, including the capsule, synovial membrane, hyaline cartilage surfaces, and bony articulations[1].

This review provides an overview about the clinical presentation and treatment of z-joint pain with emphasis on selected patients and diagnosis.

The proposal that the lumbar z-joints might be a source of back pain had initially been communicated more than 100 years ago by Goldthwaith[2] in 1911. In 1933, the term “facet joint syndrome” was introduced[3]. With the implementation of successful operations of herniated discs by Mixter[4] in 1934, the focus was directed away from the z-joints and towards the intervertebral discs. The prevalence of zygapophysial pain is very difficult to specify. In the literature, studies with different prerequisites are found. In original prevalence studies the prevalence was 10%-20%[5]. Later studies reported prevalence rates of 27%, 31%, 38%, and 45%[6-9]. The recent investigation by DePalma et al[10] found a prevalence for z-joint pain of 31%. One reason for the incongruity between the different studies is the difference in the age of the groups studied. There is an increasing prevalence with a maximum of more than 40% up to age 70[10]. In patients with thigh pain, older age was even more predictive of z-joint pain with a predicted probability of more the 50% in 60-year-old patients and more than 85% in patients over 80 years old[11].

Although the z-joints are small, they show the features typical of synovial joints[12]. This means the facets are enclosed by a capsule. The surface of the facets is covered by cartilage, a typical synovium, and even a meniscoid exists. The z-joints of the lumbar spine are innervated from the medial branches of the dorsal rami of the spinal nerves at the same level and from the level above. The medial branch of the dorsal ramus in the lumbar spine runs over the base of the transverse process at the junction of the superior articulating process (Figure 1)[13-15]. The lumbar dorsal rami have the same number as the vertebra from which they originate. In their course, these nerves traverse structures and innervate joints caudad the segment of origin[16]. Subsequently, each medial branch passes under the mamillo-accessory ligament[17]. This ligament is responsible for the consistent location. It can be large and sometimes ossified, particularly at lower levels[17]. Outside the ligament, the medial branch sends branches to innervate the z-joint, multifidus muscle, interspinal muscles, and the interspinous ligaments[18]. The z-joints are involved in all principal movements of the spine. Possible movements are axial compression/distraction, flexion/extension, axial rotation and lateral flexion. Horizontal translation does not occur as isolated movement[19].

Pain originating from the z-joints results from noxious stimulation and is therefore a somatic pain. Z-joint pain is often associated with pain in the buttock or in the leg. However, in this case, it is a somatic referred pain and not a radicular pain. Referred pain occurs because of a misperception of the region of the signal that reaches the brain by a convergent sensory pathway[20]. Somatic referred pain is perceived deeply. It is diffuse and hard to localize and it is aching in quality[21]. Pain at the beginning of a movement is typical for joints. Therefore, the z-joints often hurt when moving from a sitting to a standing position or while sleeping when turning from one side to the other. Morning stiffness with difficulty to put on socks in a standing position and pain early in the morning that is relieved during the next hours and with walking will be reported often.

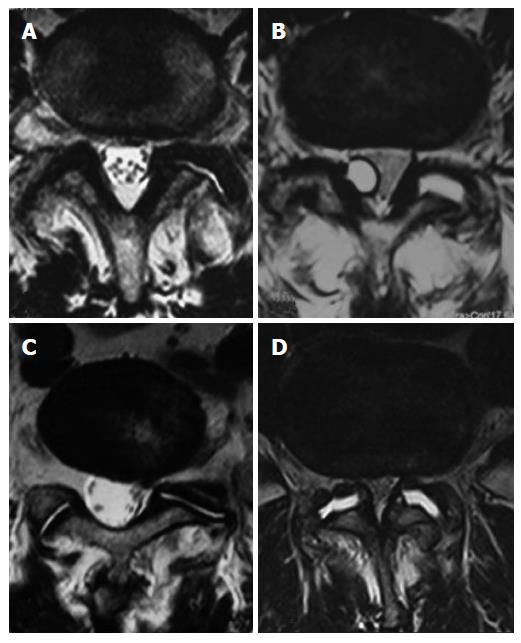

No historic or physical examination variables exist to identify a z-joint as the pain source[22,23]. Target joints can be recognized by the pain pattern, local tenderness over the area, and provocation of pain with deep pressure. The neurological examination is usually normal. Pain is the most common reason why patients undergo imaging of the spine[24], however, the the routine use of radiological imaging to diagnose z-joint pain is not supported by evidence in the literature[25-30]. The majority of clinical investigations testify no correlation between the clinical symptoms of low back pain and degenerative changes observed on radiological imaging, including radiographs, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figure 2), computed tomography (CT), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and radionuclide bone scanning[28-30]. Specifically, the association between degenerative changes in the lumbar z-joints and symptomatic low back pain remains unclear and is a subject of discussion[25-28].

The most accepted method[31] for diagnosing z-joint pain are controlled medial branch blocks (MBBs). MBBs are a diagnostic tool designed to test whether the pain stems from the z-joint because the medial branch innervates it[32]. They are the most thoroughly validated of all spinal interventional procedures[33,34]. The target nerve (medial branch of the dorsal ramus) is anaesthetized with a small volume of local anesthetic. The medial branch cannot be regarded as mediating the pain, if the pain is not relieved after a MBBs, this means the z-joint is not the pain source. A new suggestion about the pain source is necessary. If case of a positive answer, the pain source is recognized and a good chance of obtaining pain relief after denervation of the nerve is expected[35,36]. Single diagnostic blocks are not valid because they have an unacceptable high false-positive rate of 25%-45%[5-9,31]. To reduce the possibility of responses being false-positive, controlled blocks are mandatory[29]. Uncontrolled blocks or intra-articular blocks lack validity[31].

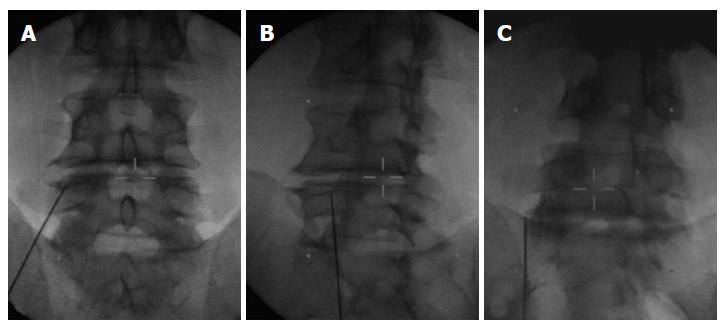

No specific conservative treatment for z-joint pain exists. Patients with z-joint pain are treated in the same way as patients with low back pain emerging from a different pain source. Guidelines only exist for radiofrequency denervation of the z-joints, published by the International Spine Intervention Society[16]. Radiofrequency denervation is the direct consequence after the diagnosis of z-joint pain has been validated by controlled MBBs and it is the only validated treatment for pain mediated by the medial branches[29]. Percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy offers pain relief by denervation of the painful joints. It is a percutaneous therapeutic procedure in which a radiofrequency electrode is used to coagulate the medial branches of the lumbar dorsal rami, or the L5 dorsal ramus, in order to relieve back pain mediated by these nerves (Figure 3)[14].

The available data vindicate the use of lumbar medial branch neurotomy provided that the correct surgical technique is used and patients are selected rigorously using controlled blocks[16,31]. There are no data that vindicate any other technique[16]. If the criterion for a positive response to diagnostic blocks is raised to complete relief, some 56% of patients obtain complete relief of pain[37]. They return to their normal activities, and the need for other health care is eliminated.

Particularly well studied is z-joint pain in patients without comorbidities. In this group of patients, diagnostic standards can be applied best and success rates after a specific therapy can be measured. In this review, the significance of z-joint pain is elaborated in patient groups in which z-joint pain is clinically relevant but does not occur as an isolated and independent disease. It is thus expected that diagnostic and therapeutic methods are only partially successful. For the patients, this can nevertheless make a significant difference in their daily lives.

During life, changes occur to the intervertebral disc and to the z-joints called spondylosis or osteoarthrosis. After the fifth decade, the subchondral bone of the z-joint gets thinner[38]. Severe or repeated pressure may result in erosions and focal thinning of the cartilage (Figure 4). These changes are not a disease per se but an expression of the morphological consequences of stress applied to the disc and the joints during life. The incidence of osteoarthrosis is just as great in patients with symptoms as in patients without symptoms[39,40]. Additional factors must be present to make the z-joints a pain source.

Z-joints are commonly altered by osteoarthritis. The arthritis is usually secondary to disc degeneration or spondylosis[41], but in 20% of cases it can be totally independent[42]. This condition is believed to be a possible cause of z-joint pain[43-46]. Inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines, prostaglandins, and neuropeptides, increase within the joint and the dorsal root ganglion in joint inflammation and arthritis[47-49]. Specifically, prostaglandin E2 has been identified as a key mediator of inflammation and amplified neuronal excitability[50-52].

Synovial cysts arise from the z-joint capsule of the lumbar spine (Figure 2B)[53]. They contain serous, gelatinous, or hemorrhagic fluid and are sometimes lined with synovium[54]. The development is related to degenerative spondylosis, segmental instability, and perhaps trauma[54,55]. They are a cause of back pain and radiculopathy, with z-joint degeneration being the most common cause for cyst formation[56].

A temporary one-sided load is often found in the context of knee or hip problems with appropriate gait disturbance or when walking with crutches. These patients often develop z-joint pain without structural changes. The reason is unusual strain or overuse of the joint. The treatment prognosis is good. Facet tropism (asymmetry of the facet angles) may have an association with degenerative changes in the spine, either as the cause of degenerative changes or as the result of abnormal loads produced by degeneration[57]. These degenerative changes can be a cause of back pain[57]. The clinical significance of facet tropism is not yet well proven[57-62].

Degenerative changes are more common in older age. The joints can be affected by osteoarthritis, which is believed to be a possible cause of z-joint pain[43-46]. Compared with other sources of low back pain (e.g., discogenic pain or sacroiliac joint pain), z-joint pain becomes the most important pain source[11]. However, there is often an image of mixed pain of various causes. Especially in combination with discogenic changes, spinal canal stenosis and degenerative spondylolisthesis several pain sources might exist.

Patients with a spinal canal stenosis on the one hand have a symptomatology coming from the stenosis and the compression of the nerves in the dural sac. These symptoms are called claudicatio spinalis and are manifested in a restricted walking distance with pain, a sensory disturbance in the legs, or even neurologic deficits. On the other hand the most important reason for the development of a spinal canal stenosis is the destruction of the z-joints[63]. Therefore, patients suffer at the same time from pain deriving from the z-joints. Epidural steroid injections are commonly used to relieve symptoms caused by lumbar spinal stenosis[64,65]. Treatment of z-joint pain as described above, including radiofrequency neurotomy is an alternative for patients for whom back pain is prominent and for patients with high risk of bleeding[66].

The loss of the normal structural support as seen in arthritis of the z-joints is the main local reason that probably leads to the development of degenerative vertebral slippage[67,68]. It seems to be obvious that morphological deformities of z-joints in the lumbar spine are an important cause of low back pain and segmental instability and a predisposing factor in the development of degenerative spondylolisthesis[69-71]. One of the most probable sources of pain related to degenerative spondylolisthesis are degenerated and subluxated z-joints and segmental instability which causes tension in the z-joint capsule and ligaments[67,70]. Spinal instability is often indicated by an increase of the joint volume[72], or synovial cysts associated with degenerative spondylolisthesis and z-joint osteoarthritis can be found[73]. An increased amount of fluid in the joint gap seen on axial MRI (Figure 2D) is significantly suggestive of spondylolisthesis[74].

It is well known that patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis also have sources of pain other than the z-joints[75]. In particular, the often additionally present spinal canal stenosis causes symptoms. The second pathology often interlinked with degenerative spondylolisthesis is disk degeneration[67,68], Spondylolisthesis is a characteristic example of concurrent pain sources in the same patient at the same time. The proportion by which the z-joints are involved in the complex symptoms is often difficult to diagnose[76].

Radiofrequency denervation is a rational treatment of low back pain in patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis because morphological deformities of the lumbar z-joints are a predisposing factor in the progress of degenerative spondylolisthesis[70], pathology of the z-joints is a important cause of low back pain within the lumbar spine[69]. An adequate pain reduction can be realized in 65% of the treated patients for a reasonable time[76,77].

Z-joints are an important pain source not only in patients with chronic low back pain but also in patients after disc surgery[78-80]. Therefore, a specific therapy against z-joint pain is rational. Continued pain following lumbar spine surgery has been assumed to be secondary to multiple causes, including epidural fibrosis, acquired stenosis, sacroiliac joint pain, and z-joint pain[81-83]. It is difficult in post lumbar surgery syndrome to identify pain-generating structures[84]. The prevalence of z-joint pain in patients with post lumbar laminectomy syndrome is 32%. In patients after disc surgery, the prevalence of z-joint pain is 7% and 28% in patients with persistent back pain after surgery[79].

The reasons why the z-joints are involved even if the joint was untouched during the operation might be inflammatory processes, low-level trauma, changes in disc height, or stretching of the joint capsule[23]. The process of degenerative disc disease, particularly when enhanced by a herniated disc or discectomy, results in progressive loss of intervertebral disc volume and disc height and increased load to the joints, which might be a reason for pain[85]. Z-joint pain can be identified and treated with a radiofrequency neurotomy with a success rate of 58.8%[79] in patients after disc surgery.

After spinal fusion, z-joint pain can occur due to residual mobility in the index segment or in adjacent segments due to overload. Studies on the effectiveness of a specific joint therapy after spinal fusion do not exist.

Z-joint pain is expected to appear with repetitive, chronic strains as might be seen in the elderly, or after an acute incident such as tearing the capsule of the joint by extending it beyond its physiologic limits. This theory is supported by clinical studies showing a higher prevalence of facet arthropathy in elderly patients[86-88] and numerous cases of lumbar facet arthropathy after high-energy trauma[89]. There is also evidence that cervical z-joints can be injured by whiplash injury and can become painful[90]. Studies using double-blind controlled MBBs found that the prevalence of pain deriving from one or multiple z-joints was between 54% and 60% amongst patients with chronic neck pain after whiplash; 27% of consecutive patients with neck pain and/or headache after whiplash had pain stemming from the C2/3 joint[91-93]. The level of symptomatic joints is consistent with the location foreseen by biomechanical studies: joints at C5/6 or C6/7 and at C2/3 are most commonly affected[94-96]. A placebo-controlled trial and several observational studies with long-term follow-up[97-102] have shown that percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy can eliminate chronic neck pain after whiplash injury stemming from the z-joints in approximately 70% of treated patients.

Lumbar facet dislocation was reported in more than two dozen patients after rapid deceleration injuries[89,103-105]. The mechanism of injury in these cases is supposed to be a combination of hyperflexion, distraction, and rotation[89,103,106,107]. Both in biomechanical studies and in postmortem studies, capsular tears, capsular avulsion, subchondral fractures, intra-articular hemorrhage, and fractures of the articular process have been found[20,108-112]. Fractures of the z-joints cannot be detected on plain radiographs and might be too small to be seen in CT scans[111,112]. Lesions such as capsular tears cannot be detected by radiography, CT, or MRI. It may be that these lesions underlie z-joint pain[1].

Z-joints meet all prerequisites to be a pain source. They are often involved in back pain and radiating pain and should not be underestimated. The prevalence of isolated z-joint pain increases with age. In addition, z-joint pain also appears in combination with other common spine diseases, such as disc degeneration, spinal canal stenosis, and spondylolisthesis. If the diagnosis is made with controlled MBBs, radiofrequency denervation is the only validated treatment for pain mediated by the medial branches.

P- Reviewer: Ahmed AS, Charles B, DeSousa K, Sandblom G, Tufan M S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK

| 1. | Cohen SP, Raja SN. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of lumbar zygapophysial (facet) joint pain. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:591-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 301] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Goldthwaith JE. The lumbosacral articulation. An explanation of many cases of lumbago, sciatica and paraplegia. Boston Med Surg J. 1911;64:365-72. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ghormley RK. Low back pain with special reference to the articular facets, with presentation of an operative procedure. JAMA. 1933;101:1773-1777. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Brunori A, De Caro GM, Giuffrè R. [Surgery of lumbar disk hernia: historical perspective]. Ann Ital Chir. 1998;69:285-293. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, Fortin J, Kine G, Bogduk N. The false-positive rate of uncontrolled diagnostic blocks of the lumbar zygapophysial joints. Pain. 1994;58:195-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Manchukonda R, Manchikanti KN, Cash KA, Pampati V, Manchikanti L. Facet joint pain in chronic spinal pain: an evaluation of prevalence and false-positive rate of diagnostic blocks. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:539-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Manchikanti L, Boswell MV, Singh V, Pampati V, Damron KS, Beyer CD. Prevalence of facet joint pain in chronic spinal pain of cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2004;5:15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Fellows B, Bakhit CE. The diagnostic validity and therapeutic value of lumbar facet joint nerve blocks with or without adjuvant agents. Curr Rev Pain. 2000;4:337-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Manchikanti L, Pampati V, Fellows B, Bakhit CE. Prevalence of lumbar facet joint pain in chronic low back pain. Pain Physician. 1999;2:59-64. [PubMed] |

| 10. | DePalma MJ, Ketchum JM, Saullo T. What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role? Pain Med. 2011;12:224-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 323] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Laplante BL, Ketchum JM, Saullo TR, DePalma MJ. Multivariable analysis of the relationship between pain referral patterns and the source of chronic low back pain. Pain Physician. 2012;15:171-178. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Bogduk N. Clinical and Radiological Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine. 5th revised edition. The zygapophysial joints-detailed structure. Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone, 2012: 29-38. . |

| 13. | Klessinger S. Facet joint pain: presentation and treatment. Is it a myth? Advanced concepts in lumbar degenerative disk disease. Heidelberg: Springer, In press. . |

| 14. | Klessinger S. Denervation of the Zygapophysial Joints of the Cervical and Lumbar Spine. Tech Orthop. 2013;28:23-34. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bogduk N, Long DM. The anatomy of the so-called „articular nerves“ and their relationship to facet denervation in the treatment of low-back pain. J Neurosurg. 1979;51:172-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bogduk N. Practice Guidelines for Spinal Diagnostic and Treatment Procedures. International Spine Intervention Society. 2nd ed. Lumbar medial branch thermal radiofrequency neurotomy, 2013: 601-629. . |

| 17. | Bogduk N. The lumbar mamillo--accessory ligament. Its anatomical and neurosurgical significance. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1981;6:162-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bogduk N. The innervation of the lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1983;8:286-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 393] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bogduk N. Clinical and Radiological Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine. 5th revised edition. Movements of the lumbar spine. Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone, 2012: 73-92. . |

| 20. | Bogduk N. Clinical and Radiological Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine. 5th revised edition. Low back pain. Elsevier, Churchill Livingstone, 2012: 173-205. . |

| 21. | Bogduk N. On the definitions and physiology of back pain, referred pain, and radicular pain. Pain. 2009;147:17-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hancock MJ, Maher CG, Latimer J, Spindler MF, McAuley JH, Laslett M, Bogduk N. Systematic review of tests to identify the disc, SIJ or facet joint as the source of low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:1539-1550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | van Kleef M, Vanelderen P, Cohen SP, Lataster A, Van Zundert J, Mekhail N. 12. Pain originating from the lumbar facet joints. Pain Pract. 2010;10:459-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bogduk N. Degenerative joint disease of the spine. Radiol Clin North Am. 2012;50:613-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Badgley CE. The articular facets in relation to low-back pain and sciatic radiation. J Bone Joint Surg. 1941;23:481-496. |

| 26. | Nachemson AL. Newest knowledge of low back pain. A critical look. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;179:8-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, Fortin J, Kine G, Bogduk N. Clinical features of patients with pain stemming from the lumbar zygapophysial joints. Is the lumbar facet syndrome a clinical entity? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19:1132-1137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 401] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Schwarzer AC, Wang SC, O‘Driscoll D, Harrington T, Bogduk N, Laurent R. The ability of computed tomography to identify a painful zygapophysial joint in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:907-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Selby DK, Paris SV. Anatomy of facet joints and its correlation with low back pain. Contemp Orthop. 1981;312:1097-1103. |

| 30. | Lehman VT, Murphy RC, Kaufmann TJ, Diehn FE, Murthy NS, Wald JT, Thielen KR, Amrami KK, Morris JM, Maus TP. Frequency of discordance between facet joint activity on technetium Tc99m methylene diphosphonate SPECT/CT and selection for percutaneous treatment at a large multispecialty institution. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2014;35:609-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bogduk N. Practice Guidelines for Spinal Diagnostic and Treatment Procedures. International Spine Intervention Society. 2nd ed. Lumbar medial branch blocks, 2013: 559-600. . |

| 32. | Klessinger S. Medial Branch Blocks of the Cervical and Lumbar Spine. Tech Orthop. 2013;1:18-22. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bogduk N. Diagnostik nerve blocks in chronic pain. In: Breivik H, Shipley M, editors. Pain. Best Practice and Research Compendium. Elsevier, Edingurgh 2007; 47-55. |

| 34. | Schliessbach J, Siegenthaler A, Heini P, Bogduk N, Curatolo M. Blockade of the sinuvertebral nerve for the diagnosis of lumbar diskogenic pain: an exploratory study. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:204-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Bogduk N; International Spine Intervention Society. Lumbar Medial Branch Blocks. Practice Guidelines for Spinal Diagnostic and Treatment Procedures. San Francisco, CA: International Spine Intervention Society 2004; 47-65. |

| 36. | Bogduk N, Dreyfuss P, Govind J. A narrative review of lumbar medial branch neurotomy for the treatment of back pain. Pain Med. 2009;10:1035-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | MacVicar J, Borowczyk JM, MacVicar AM, Loughnan BM, Bogduk N. Lumbar medial branch radiofrequency neurotomy in New Zealand. Pain Med. 2013;14:639-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Twomey L, Taylor J. Age changes in lumbar intervertebral discs. Acta Orthop Scand. 1985;56:496-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Torgerson WR, Dotter WE. Comparative roentgenographic study of the asymptomatic and symptomatic lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58:850-853. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Lawrence JS, Bremner JM, Bier F. Osteo-arthrosis. Prevalence in the population and relationship between symptoms and x-ray changes. Ann Rheum Dis. 1966;25:1-24. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Vernon-Roberts B, Pirie CJ. Degenerative changes in the intervertebral discs of the lumbar spine and their sequelae. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1977;16:13-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Mooney V, Robertson J. The facet syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;115:149-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Eisenstein SM, Parry CR. The lumbar facet arthrosis syndrome. Clinical presentation and articular surface changes. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69:3-7. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Abel MS. The radiology of low back pain associated with posterior element lesions of the lumbar spine. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1984;20:311-352. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Carrera GF, Williams AL. Current concepts in evaluation of the lumbar facet joints. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1984;21:85-104. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Lynch MC, Taylor JF. Facet joint injection for low back pain. A clinical study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1986;68:138-141. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Willburger RE, Wittenberg RH. Prostaglandin release from lumbar disc and facet joint tissue. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19:2068-2070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Tachihara H, Kikuchi S, Konno S, Sekiguchi M. Does facet joint inflammation induce radiculopathy?: an investigation using a rat model of lumbar facet joint inflammation. Spine. 2007;32:406-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Dong L, Guarino BB, Jordan-Sciutto KL, Winkelstein BA. Activating transcription factor 4, a mediator of the integrated stress response, is increased in the dorsal root ganglia following painful facet joint distraction. Neuroscience. 2011;193:377-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Bär KJ, Natura G, Telleria-Diaz A, Teschner P, Vogel R, Vasquez E, Schaible HG, Ebersberger A. Changes in the effect of spinal prostaglandin E2 during inflammation: prostaglandin E (EP1-EP4) receptors in spinal nociceptive processing of input from the normal or inflamed knee joint. J Neurosci. 2004;24:642-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Lin CR, Amaya F, Barrett L, Wang H, Takada J, Samad TA, Woolf CJ. Prostaglandin E2 receptor EP4 contributes to inflammatory pain hypersensitivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:1096-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Vasquez E, Bär KJ, Ebersberger A, Klein B, Vanegas H, Schaible HG. Spinal prostaglandins are involved in the development but not the maintenance of inflammation-induced spinal hyperexcitability. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9001-9008. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Mattei TA, Goulart CR, McCall TD. Pathophysiology of regression of synovial cysts of the lumbar spine: the ‘anti-inflammatory hypothesis’. Med Hypotheses. 2012;79:813-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Shin KM, Kim MS, Ko KM, Jang JS, Kang SS, Hong SJ. Percutaneous aspiration of lumbar zygapophyseal joint synovial cyst under fluoroscopic guidance -A case report-. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2012;62:375-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Sabo RA, Tracy PT, Weinger JM. A series of 60 juxtafacet cysts: clinical presentation, the role of spinal instability, and treatment. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:560-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Bao H, Kommadath A, Sun X, Meng Y, Arantes AS, Plastow GS, Guan LL, Stothard P. Expansion of ruminant-specific microRNAs shapes target gene expression divergence between ruminant and non-ruminant species. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Kalichman L, Suri P, Guermazi A, Li L, Hunter DJ. Facet orientation and tropism: associations with facet joint osteoarthritis and degeneratives. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:E579-E585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Berlemann U, Jeszenszky DJ, Bühler DW, Harms J. Facet joint remodeling in degenerative spondylolisthesis: an investigation of joint orientation and tropism. Eur Spine J. 1998;7:376-380. [PubMed] |

| 59. | Boden SD, Riew KD, Yamaguchi K, Branch TP, Schellinger D, Wiesel SW. Orientation of the lumbar facet joints: association with degenerative disc disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:403-411. [PubMed] |

| 60. | Fujiwara A, Tamai K, An HS, Lim TH, Yoshida H, Kurihashi A, Saotome K. Orientation and osteoarthritis of the lumbar facet joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;385:88-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Grogan J, Nowicki BH, Schmidt TA, Haughton VM. Lumbar facet joint tropism does not accelerate degeneration of the facet joints. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:1325-1329. [PubMed] |

| 62. | Sato K, Wakamatsu E, Yoshizumi A, Watanabe N, Irei O. The configuration of the laminas and facet joints in degenerative spondylolisthesis. A clinicoradiologic study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1989;14:1265-1271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Aebi M. The adult scoliosis. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:925-948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 552] [Cited by in RCA: 585] [Article Influence: 29.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Manchikanti L, Cash KA, McManus CD, Damron KS, Pampati V, Falco FJ. A randomized, double-blind controlled trial of lumbar interlaminar epidural injections in central spinal stenosis: 2-year follow-up. Pain Physician. 2015;18:79-92. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Friedly JL, Comstock BA, Turner JA, Heagerty PJ, Deyo RA, Sullivan SD, Bauer Z, Bresnahan BW, Avins AL, Nedeljkovic SS. A randomized trial of epidural glucocorticoid injections for spinal stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:11-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Hwang SY, Lee JW, Lee GY, Kang HS. Lumbar facet joint injection: feasibility as an alternative method in high-risk patients. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:3153-3160. [PubMed] |

| 67. | Kalichman L, Hunter DJ. Diagnosis and conservative management of degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:327-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Sengupta DK, Herkowitz HN. Degenerative spondylolisthesis: review of current trends and controversies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:S71-S81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Berven S, Tay BB, Colman W, Hu SS. The lumbar zygapophyseal (facet) joints: a role in the pathogenesis of spinal pain syndromes and degenerative spondylolisthesis. Semin Neurol. 2002;22:187-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Dai LY. Orientation and tropism of lumbar facet joints in degenerative spondylolisthesis. Int Orthop. 2001;25:40-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Fitzgerald JA, Newman PH. Degenerative spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976;58:184-192. [PubMed] |

| 72. | Hasegawa K, Kitahara K, Shimoda H, Hara T. Facet joint opening in lumbar degenerative diseases indicating segmental instability. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;12:687-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Alicioglu B, Sut N. Synovial cysts of the lumbar facet joints: a retrospective magnetic resonance imaging study investigating their relation with degenerative spondylolisthesis. Prague Med Rep. 2009;110:301-309. [PubMed] |

| 74. | Schinnerer KA, Katz LD, Grauer JN. MR findings of exaggerated fluid in facet joints predicts instability. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21:468-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Jensen TS, Karppinen J, Sorensen JS, Niinimäki J, Leboeuf-Yde C. Vertebral endplate signal changes (Modic change): a systematic literature review of prevalence and association with non-specific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:1407-1422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 337] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Klessinger S. Radiofrequency neurotomy for treatment of low back pain in patients with minor degenerative spondylolisthesis. Pain Physician. 2012;15:E71-E78. [PubMed] |

| 77. | Klessinger S. In response: does the diagnosis of spondylolisthesis matter? Pain Physician. 2012;15:E158. |

| 78. | Klessinger S. Radiofrequency neurotomy for the treatment of therapy-resistant neck pain after ventral cervical operations. Pain Med. 2010;11:1504-1510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Klessinger S. Zygapophysial joint pain in post lumbar surgery syndrome. The efficacy of medial branch blocks and radiofrequency neurotomy. Pain Med. 2013;14:374-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Klessinger S. The benefit of therapeutic medial branch blocks after cervical operations. Pain Physician. 2010;13:527-534. [PubMed] |

| 81. | Fritsch EW, Heisel J, Rupp S. The failed back surgery syndrome: reasons, intraoperative findings, and long-term results: a report of 182 operative treatments. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:626-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Manchikanti L, Singh V, Cash KA, Pampati V, Datta S. Management of pain of post lumbar surgery syndrome: one-year results of a randomized, double-blind, active controlled trial of fluoroscopic caudal epidural injections. Pain Physician. 2010;13:509-521. [PubMed] |

| 83. | Manchikanti L, Singh V, Cash KA, Pampati V, Datta S. Preliminary results of a randomized, equivalence trial of fluoroscopic caudal epidural injections in managing chronic low back pain: Part 3--Post surgery syndrome. Pain Physician. 2008;11:817-831. [PubMed] |

| 84. | Manchikanti L, Manchukonda R, Pampati V, Damron KS, McManus CD. Prevalence of facet joint pain in chronic low back pain in postsurgical patients by controlled comparative local anesthetic blocks. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;88:449-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Burton CV, Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Yong-Hing K, Heithoff KB. Causes of failure of surgery on the lumbar spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981;157:191-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Revel ME, Listrat VM, Chevalier XJ, Dougados M, N‘guyen MP, Vallee C, Wybier M, Gires F, Amor B. Facet joint block for low back pain: identifying predictors of a good response. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;73:824-828. [PubMed] |

| 87. | Revel M, Poiraudeau S, Auleley GR, Payan C, Denke A, Nguyen M, Chevrot A, Fermanian J. Capacity of the clinical picture to characterize low back pain relieved by facet joint anesthesia. Proposed criteria to identify patients with painful facet joints. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998;23:1972-1976; discussion 1977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Jackson RP, Jacobs RR, Montesano PX. 1988 Volvo award in clinical sciences. Facet joint injection in low-back pain. A prospective statistical study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1988;13:966-971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Song KJ, Lee KB. Bilateral facet dislocation on L4-L5 without neurologic deficit. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18:462-464. [PubMed] |

| 90. | Curatolo M, Bogduk N, Ivancic PC, McLean SA, Siegmund GP, Winkelstein BA. The role of tissue damage in whiplash-associated disorders: discussion paper 1. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36:S309-S315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Lord SM, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, Bogduk N. Chronic cervical zygapophysial joint pain after whiplash. A placebo-controlled prevalence study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1996;21:1737-1744; discussion 1744-1745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 390] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Barnsley L, Lord SM, Wallis BJ, Bogduk N. The prevalence of chronic cervical zygapophysial joint pain after whiplash. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1995;20:20-25; discussion 26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 362] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Lord SM, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, Bogduk N. Third occipital nerve headache: a prevalence study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:1187-1190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Kaneoka K, Ono K, Inami S, Hayashi K. Motion analysis of cervical vertebrae during whiplash loading. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:763-769; discussion 770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Cusick JF, Pintar FA, Yoganandan N. Whiplash syndrome: kinematic factors influencing pain patterns. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:1252-1258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Pearson AM, Ivancic PC, Ito S, Panjabi MM. Facet joint kinematics and injury mechanisms during simulated whiplash. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2004;29:390-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Lord SM, Barnsley L, Wallis BJ, McDonald GJ, Bogduk N. Percutaneous radio-frequency neurotomy for chronic cervical zygapophyseal-joint pain. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1721-1726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 607] [Cited by in RCA: 461] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | McDonald GJ, Lord SM, Bogduk N. Long-term follow-up of patients treated with cervical radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic neck pain. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:61-67; discussion 67-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Govind J, King W, Bailey B, Bogduk N. Radiofrequency neurotomy for the treatment of third occipital headache. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:88-93. [PubMed] |

| 100. | Barnsley L. Percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic neck pain: outcomes in a series of consecutive patients. Pain Med. 2005;6:282-286. [PubMed] |

| 101. | MacVicar J, Borowczyk JM, MacVicar AM, Loughnan BM, Bogduk N. Cervical medial branch radiofrequency neurotomy in New Zealand. Pain Med. 2012;13:647-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Klessinger S. Cervical medial branch radiofrequency neurotomy. Pain Med. 2012;13:621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Das De S, McCreath SW. Lumbosacral fracture-dislocations. A report of four cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;63-B:58-60. [PubMed] |

| 104. | Fabris D, Costantini S, Nena U, Lo Scalzo V. Traumatic L5-S1 spondylolisthesis: report of three cases and a review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 1999;8:290-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Kaplan SS, Wright NM, Yundt KD, Lauryssen C. Adjacent fracture-dislocations of the lumbosacral spine: case report. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:1134-1137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Verlaan JJ, Oner FC, Dhert WJ, Verbout AJ. Traumatic lumbosacral dislocation: case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:1942-1944. [PubMed] |

| 107. | Veras del Monte LM, Bagó J. Traumatic lumbosacral dislocation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:756-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Adams MA, Hutton WC. The relevance of torsion to the mechanical derangement of the lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1981;6:241-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Lamy C, Bazergui A, Kraus H, Farfan HF. The strength of the neural arch and the etiology of spondylolysis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1975;6:215-231. [PubMed] |

| 110. | Sullivan JD, Farfan HF. The crumpled neural arch. Orthop Clin North Am. 1975;6:199-214. [PubMed] |

| 111. | Taylor JR, Twomey LT, Corker M. Bone and soft tissue injuries in post-mortem lumbar spines. Paraplegia. 1990;28:119-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Twomey LT, Taylor JR, Taylor MM. Unsuspected damage to lumbar zygapophyseal (facet) joints after motor-vehicle accidents. Med J Aust. 1989;151:210-212, 215-217. [PubMed] |