Copyright

©2012 Baishideng Publishing Group Co.

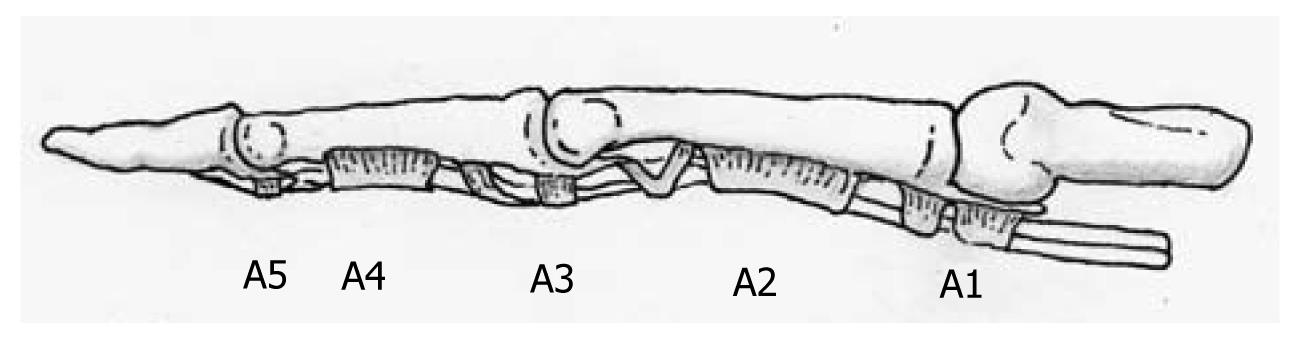

Figure 1 The pulley system of the long fingers (modified according to Schmidt and Lanz[8]).

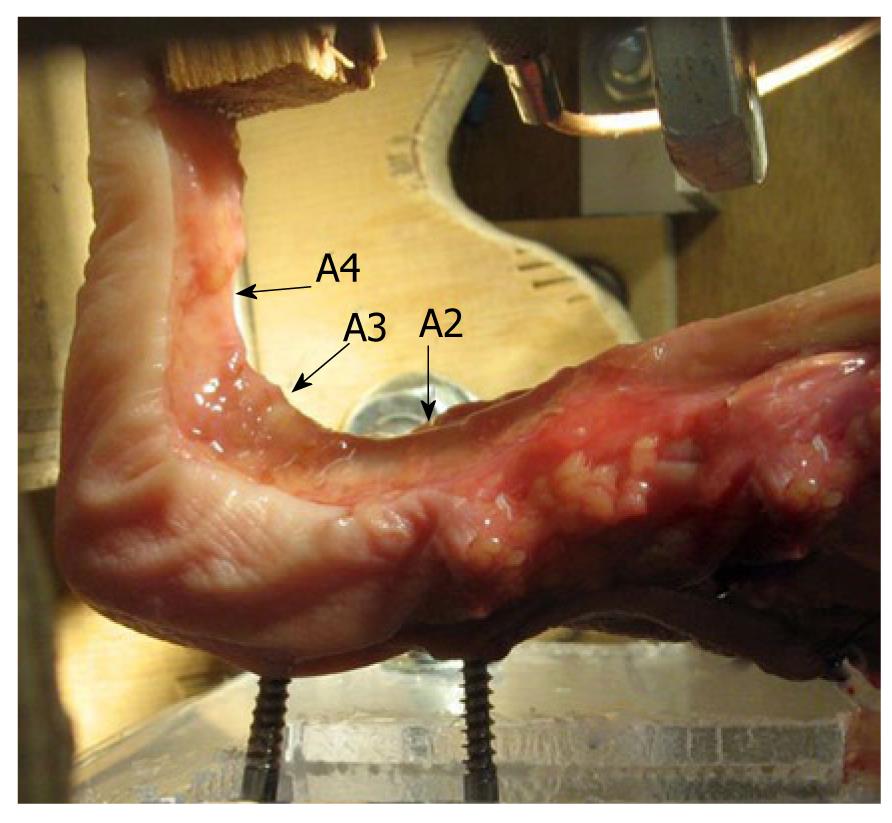

Figure 2 Complete pulley system during a stress test in the biomechanical laboratory.

(Figure with permission of Schöffl V, MD, PhD, Institute of Anatomy, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany[9]).

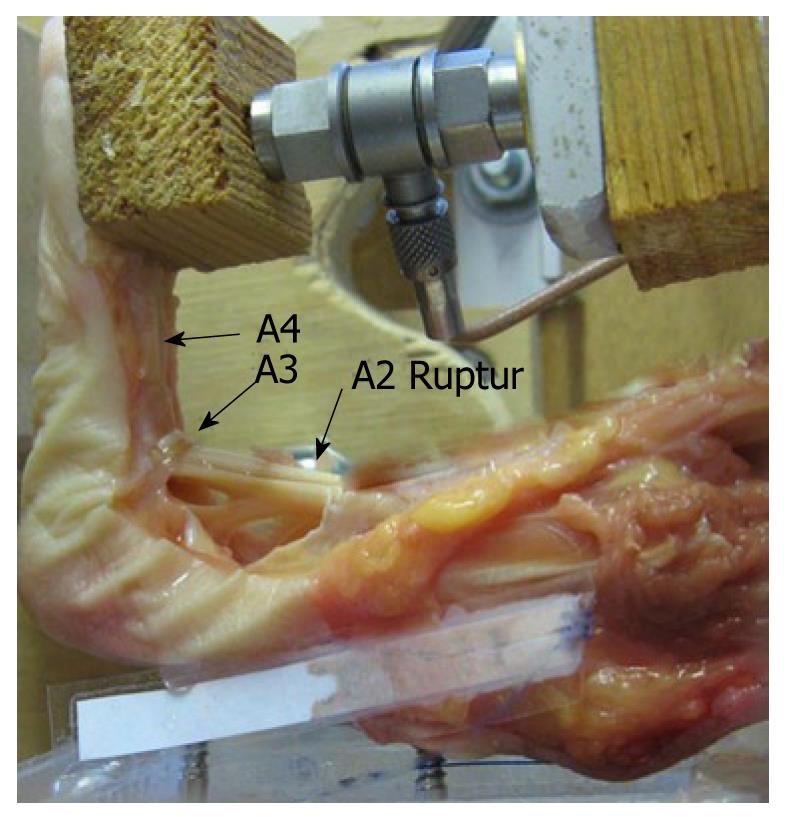

Figure 3 A2-pulley rupture during a stress test in the biomechanical laboratory.

Note the increased distance between the flexor tendons and the bone. The A3-pulley is unharmed. (Figure with permission of Schöffl V, MD, PhD, Institute of Anatomy, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany[9]).

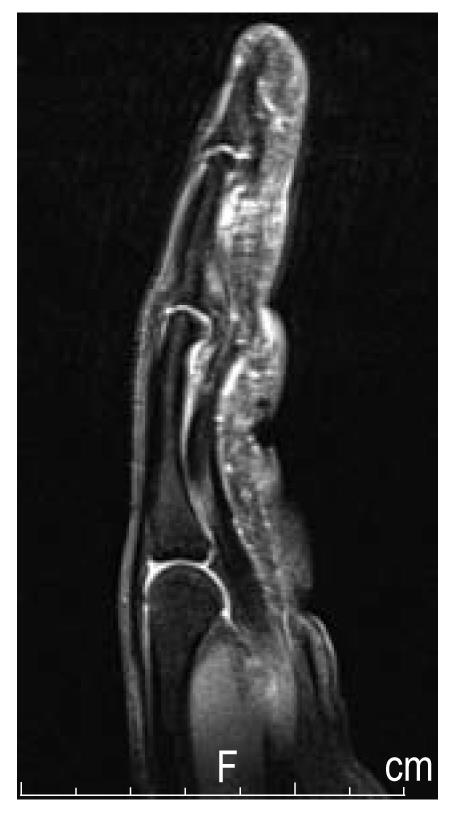

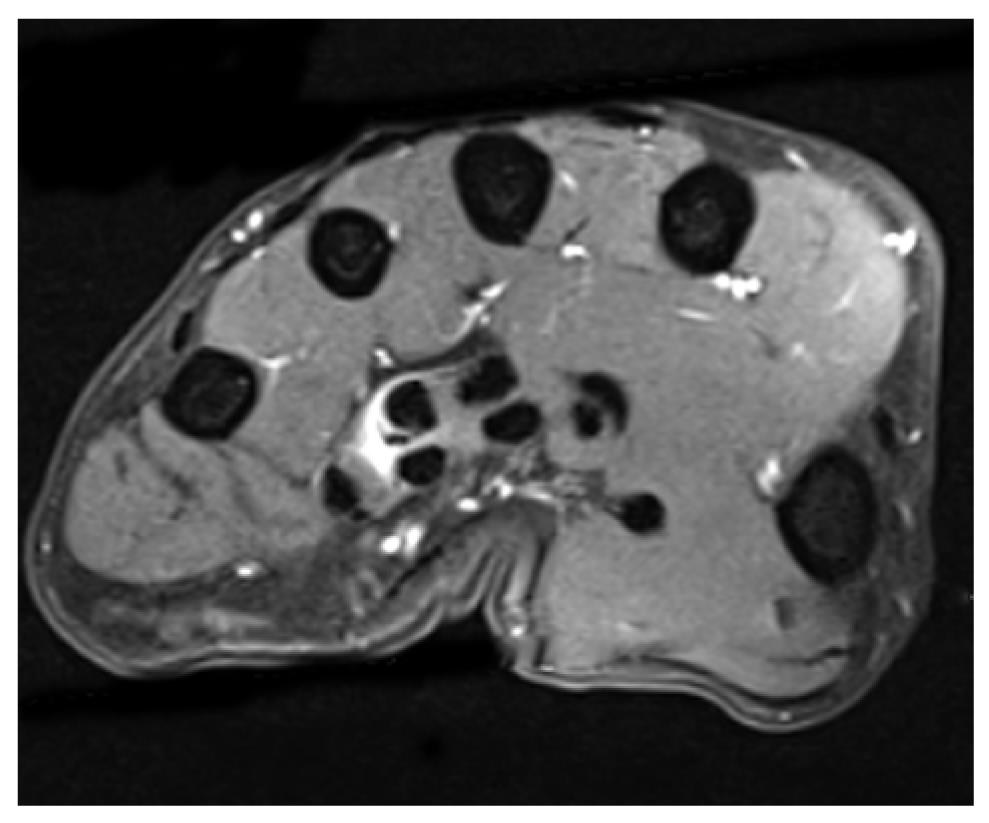

Figure 4 Closed flexor tendon rupture of the flexor digitorum profundus at the level of the middle phalanx (rock climber)[9].

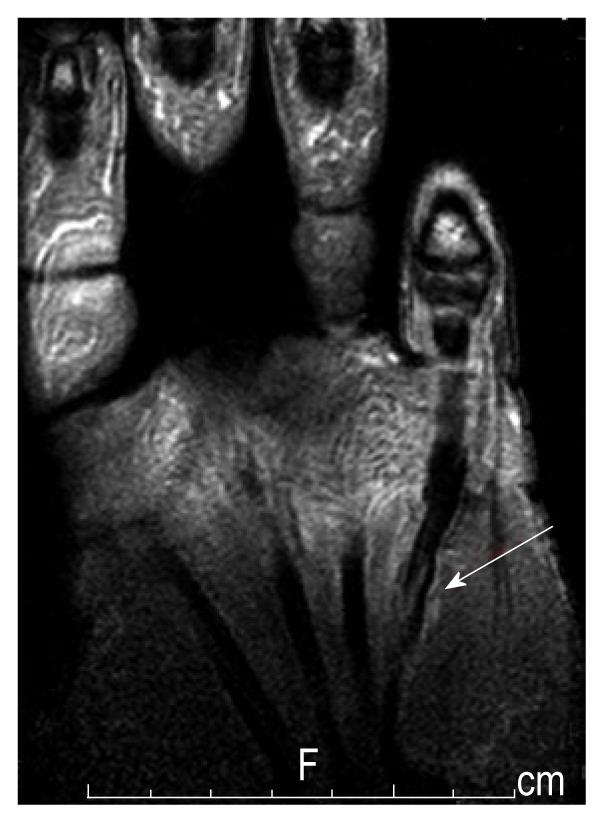

Figure 5 Lumbrical tendon rupture (note the edema and the dislocated lumbrical tendon from the flexor tendon).

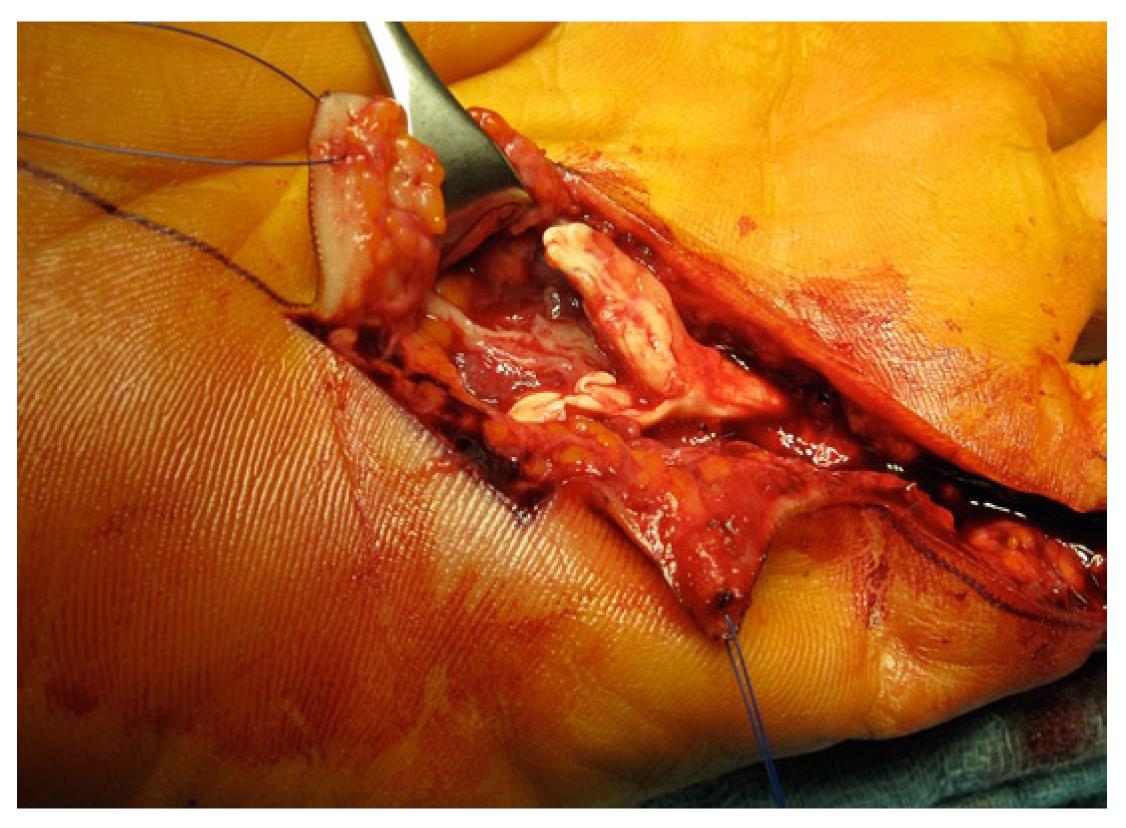

Figure 6 Degenerative flexor tendon rupture in a long term rock climber with chronic tendinosis.

Figure 7 Degenerative flexor tendon rupture in a long term rock climber with chronic tendinosis.

The histology showed a mucoid degeneration with numerous blood vessel proliferations and a siderosis as a sign of an older bleed[9].

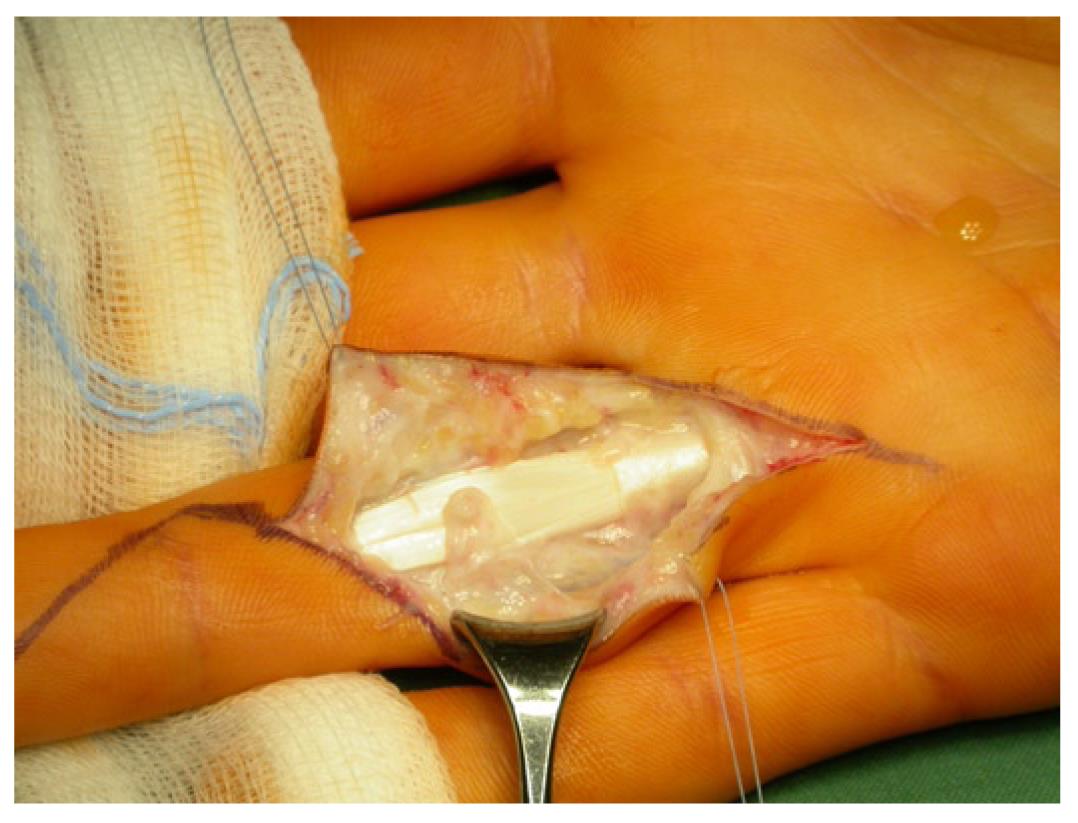

Figure 8 Ruptured A3 pulley (the tendon sheath with chronic inflammation is already removed).

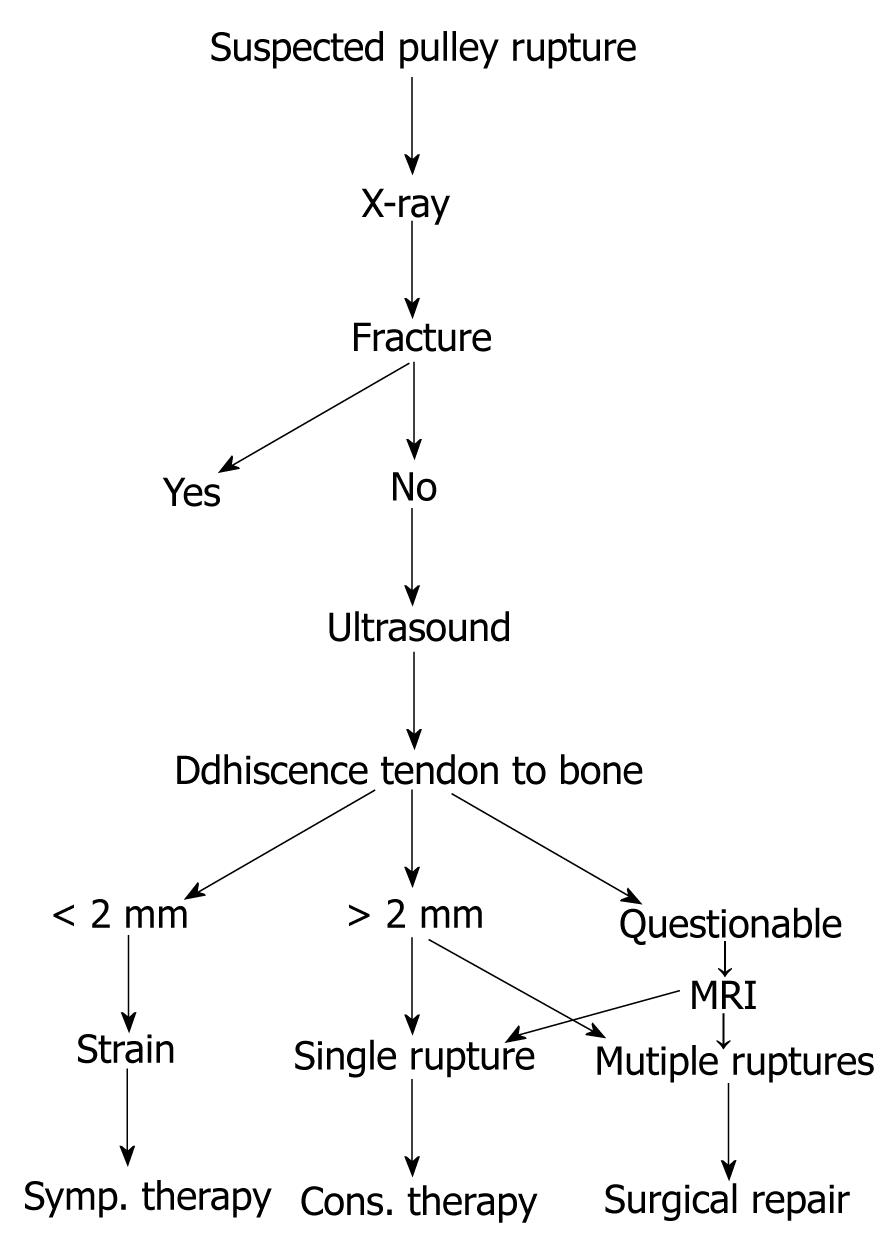

Figure 9 Algorithm for pulley injuries[3].

MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging.

- Citation: Schöffl V, Heid A, Küpper T. Tendon injuries of the hand. World J Orthop 2012; 3(6): 62-69

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v3/i6/62.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v3.i6.62