Published online Dec 10, 2015. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v6.i6.295

Peer-review started: April 21, 2015

First decision: June 3, 2015

Revised: September 14, 2015

Accepted: October 12, 2015

Article in press: October 13, 2015

Published online: December 10, 2015

Processing time: 235 Days and 22.9 Hours

Dermatomyositis is known to be associated with neoplastic disorders, however the presentation of carcinoma of unknown primary as dermatomyositis is rare. We describe a case index of 50-year-old female who presented with enlarged inguinal lymph nodes accompanied with symmetric proximal muscle weakness and erythematous plaques. Conventional basic work-up did not reveal the diagnosis, however, positron emission tomography-computed tomography and re-staining of the pathology specimen suggested the ovaries as the primary site. Chemotherapy including carboplatin paclitaxel and bevacizumab led to complete response of disease and improvement in the dermatomyositis. The present case emphasizes the importance of a thorough directed evaluation for the underlying cancer in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary presenting as dermatomyositis. We further provide an up-to-date detailed review of published data describing these clinical entities.

Core tip: The presentation of carcinoma of unknown primary as dermatomyositis is rare. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography and pathology case oriented evaluation may identify the site of origin. We provide an up-to-date detailed review of published data describing these clinical entities.

- Citation: Sonnenblick A. Carcinoma of unknown primary and paraneoplastic dermatomyositis. World J Clin Oncol 2015; 6(6): 295-298

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v6/i6/295.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v6.i6.295

Cancer of unknown primary origin (CUP) is a group of metastatic tumors for which the site of origin cannot be detected at the time of diagnosis. In most of the cases, the source of the cancer will never be determined. According to the European society of medical oncology, CUPs account for up to 5% of all malignancies[1]. The biology of these tumors is not fully elucidated although mechanism of metastatic spread in the absence of growth of the primary tumor can occur through site-specific transformation of disseminated cells, or oncogene induction at metastatic stroma.

Dermatomyositis is a connective-tissue disease characterized by progressive, proximal muscle weakness and pathognomonic cutaneous findings. Malignancy is associated with dermatomyositis in up to 40% of patients, representing a paraneoplastic phenomenon[2,3]. We describe here a rare case of a female who presented with carcinoma of unknown origin accompanied with symmetric proximal muscle weakness and erythematous plaques.

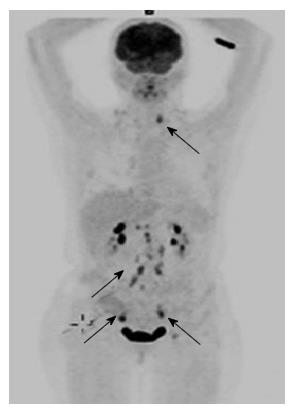

A 50-year-old woman with carcinoma of unknown origin was admitted to the E.R because of intense weakness. She was evaluated one month earlier when she underwent biopsy from enlarged left inguinal lymph node. The biopsy revealed poorly differentiated carcinoma of unknown origin (performed out of our institute). On arrival, her physical examination revealed proximal weakness, which was profound in all extremities. Skin manifestations included periorbital edema and erythematous plaques on the extremities. She had enlarged left inguinal lymph node and signs of biopsy from the right lymph node. Biochemical analysis demonstrated elevated creatine kinase 5600 u/L (normal range 26-192), elevated AST 147(normal range 0-40) and ALT 130 (normal range 0-35). A computed tomography (CT) scan was unremarkable except enlarged left inguinal lymph node. Indirect immunofluorescence for anti-Jo-1 and ANA were negative. Tumor markers showed CEA-4.16 (0-4) CA15-3 -60 (0-30) CA125 80 (0-30). The patient underwent another biopsy from the left lymph node for re-pathology evaluation and staining which showed poorly differentiated Carcinoma. Staining for keratins: CK7 - positive strong, CK20 - weak, CK5/6 - negative, WT1 - positive and TTF - negative. Gynecological evaluation, colonscopy and endoscopy where unremarkable. Since dermatomyositis is associated with gynecological - ovarian cancer there was a clinical decision to look for findings at the urogenital system. Gynecologist examination and vaginal US were unremarkable. It was then decided to perform positron emission tomography (PET)-CT scan which demonstrated increased standardized uptake values uptake in the left pelvis in an ovarian cyst and there was also high standardized uptake values uptake in paraaortic and cervival lymph node (Figure 1). These observations have led us to re-staining the specimen for CA125 and p53 which were both positive suggestive of ovarian origin. The patient begun chemotherapy treatment with protocol directed to ovarian cancer including carboplatin [Area under the curve (AUC) 6] paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 and bevacsizumab 15 mg/kg every three weeks. After 2 cycles dose reductions in both carboplatin (to AUC 4-5) and paclitaxel (to 80 mg/m2 weekly) were needed due to neuropathy and neutropenia. She also received steroids (prednisone 60 mg which was gradually tapered off and replaced with methotrexate) for dermatomyositis. This treatment (chemotherapy and/or the steroids) led to complete response in the disease and improvement in the dermatomyositis.

Few studies demonstrated that dermatomyositis and polymyositis are association with different cancers[4-6]. A pooled analysis from Scandinavian repositories, confirmed that both dermatomyositis and polymyositis are associated with malignancy (dermatomyositis more than polymyositis)[3]. This study confirmed that ovarian, lung, gastric, colorectal, and pancreatic cancers were the cancers most strongly associated with dermatomyositis but other cancers were associated with dermatomyositis as well. Cancer treatment, local (surgery) or systemic (chemotherapy) usually results in remission of the dermatomyositis, and recurrence of symptoms can represent relapse of the malignant disease, further supporting its paraneoplastic origin[7,8]. Due to the increased risk of some cancers in patients with dermatomyositis, further examinations which may include whole body imaging, mammography and gynaecological evaluation are justified.

CUPs diagnosis requires pathology evaluation[1]. CUPs are categorized by pathological evaluation into: Differentiated carcinomas (well, moderately, or poorly); undifferentiated neoplasms; squamous cell carcinomas and carcinomas with neuroendocrine differentiation. In the past CUP was characterized as an individual entity with dismal prognosis, while as our understanding of cancer biology evolved it became clear that CUP may retain the underpinnings of the primary origin[9]. Staining for keratins, may mislead the clinicians if interpreted incorrectly. For example our patients was CK7 positive and CK20 - weak - if weak is interpreted as negative, lung breast and thyroid cancers are more suspected. If CK20 - weak staining is interpreted as positive ovarian and pancreas cancers are suspected and WT-1, p53 and CA125 may add information as shown in our case. Full physical examination, blood and biochemistry analysis, and CT scans of thorax, abdomen and pelvis constitute the basic work-up in CUPs. Other evaluation should be only clinically guided. The minority of patients with CUP (less than 20%) belong to subsets with more favorable outcomes and treatment response and it is therefore crucial to identify this patients during the work-up[1,10,11]. Peritoneal carcinomatosis in females represent one example of this favorable risk CUP. Our patient pathology did not reveal serous papillary but rather poorly differentiated carcinoma. Moreover the disease distribution according the PET-CT was not classic for ovarian caner except uptake in the left ovary. However the decision to treat her with chemotherapy used for ovarian cancers seems rational.

PET-CT is one of the most sensitive imaging techniques to detect malignant lesions and has been used in different cancer conditions with quite success[12-15]. Selva-O’Callaghan et al[16] prospectively evaluated the role of PET-CT in the diagnosis of occult tumors in patients with dermatomyositis/polymyositis. Using PET-CT they evaluated prospectively 55 patients with myositis. 9 out of the 55 patients were diagnosed with cancer. PET-CT identified 6 out of the 9 patients. The authors concluded that PET-CT for diagnosing CUP in patients with myositis was an option comparable to other multi diagnostic tests.

As the radiotracer doses administered using PET-CT are relatively small, the risk is very low compared with the potential benefits. There are no known long-term adverse effects from such low-dose exposure and the potential benefits from PET-CT outweighs the risks which may include allergic reactions (rare and mild), and exposure to low amount of radiation[17].

In conclusion this rare case of patient with carcinoma of unknown primary emphasizes the importance of a thorough directed evaluation and the usage of PET-CT for the underlying cancer in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary presenting with dermatomyositis.

P- Reviewer: Garfield D, Kucherlapati MH, Yamagata M

S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Fizazi K, Greco FA, Pavlidis N, Pentheroudakis G. Cancers of unknown primary site: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2011;22 Suppl 6:vi64-vi68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dourmishev LA. Dermatomyositis associated with malignancy. 12 case reports. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1999;455:193-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, Pukkala E, Mellemkjaer L, Airio A, Evans SR, Felson DT. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357:96-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 757] [Cited by in RCA: 675] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sigurgeirsson B, Lindelöf B, Edhag O, Allander E. Risk of cancer in patients with dermatomyositis or polymyositis. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:363-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 578] [Cited by in RCA: 487] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Davis MD, Ahmed I. Ovarian malignancy in patients with dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a retrospective analysis of fourteen cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;37:730-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Barnes BE, Mawr B. Dermatomyositis and malignancy. A review of the literature. Ann Intern Med. 1976;84:68-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Verducci MA, Malkasian GD, Friedman SJ, Winkelmann RK. Gynecologic carcinoma associated with dermatomyositis-polymyositis. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;64:695-698. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Sunnenberg TD, Kitchens CS. Dermatomyositis associated with malignant melanoma. Parallel occurrence, remission, and relapse of the two processes in a patient. Cancer. 1983;51:2157-2158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Varadhachary GR, Raber MN. Cancer of Unknown Primary Site. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:757-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bugat R, Bataillard A, Lesimple T, Voigt JJ, Culine S, Lortholary A, Merrouche Y, Ganem G, Kaminsky MC, Negrier S. Summary of the Standards, Options and Recommendations for the management of patients with carcinoma of unknown primary site (2002). Br J Cancer. 2003;89 Suppl 1:S59-S66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Abbruzzese JL, Abbruzzese MC, Hess KR, Raber MN, Lenzi R, Frost P. Unknown primary carcinoma: natural history and prognostic factors in 657 consecutive patients. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1272-1280. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Linke R, Schroeder M, Helmberger T, Voltz R. Antibody-positive paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes: value of CT and PET for tumor diagnosis. Neurology. 2004;63:282-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Patel RR, Subramaniam RM, Mandrekar JN, Hammack JE, Lowe VJ, Jett JR. Occult malignancy in patients with suspected paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes: value of positron emission tomography in diagnosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:917-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Younes-Mhenni S, Janier MF, Cinotti L, Antoine JC, Tronc F, Cottin V, Ternamian PJ, Trouillas P, Honnorat J. FDG-PET improves tumour detection in patients with paraneoplastic neurological syndromes. Brain. 2004;127:2331-2338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Berner U, Menzel C, Rinne D, Kriener S, Hamscho N, Döbert N, Diehl M, Kaufmann R, Grünwald F. Paraneoplastic syndromes: detection of malignant tumors using [(18)F]FDG-PET. Q J Nucl Med. 2003;47:85-89. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Selva-O'Callaghan A, Grau JM, Gámez-Cenzano C, Vidaller-Palacín A, Martínez-Gómez X, Trallero-Araguás E, Andía-Navarro E, Vilardell-Tarrés M. Conventional cancer screening versus PET/CT in dermatomyositis/polymyositis. Am J Med. 2010;123:558-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Boellaard R, O’Doherty MJ, Weber WA, Mottaghy FM, Lonsdale MN, Stroobants SG, Oyen WJ, Kotzerke J, Hoekstra OS, Pruim J. FDG PET and PET/CT: EANM procedure guidelines for tumour PET imaging: version 1.0. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:181-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |