Published online Aug 24, 2025. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v16.i8.107757

Revised: April 22, 2025

Accepted: June 18, 2025

Published online: August 24, 2025

Processing time: 144 Days and 23.6 Hours

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a leading cause of cancer-related morbidity and mortality globally, and its management in the emergency setting presents distinct challenges. In addition to its advantages in elective CRC surgery, studies have demonstrated that minimally invasive surgery (MIS) can provide benefits in CRC emergencies, such as reduced morbidity and a shorter length of hospitalization. However, the applicability of MIS in the emergency setting is limited by factors such as compromised patient physiology, resource constraints, and the need for technical expertise. As an alternative to emergency MIS, endoscopic interventions have also been increasingly supported by emerging evidence as a bridge to surgery. This article appraises contemporary guidelines and the evidence behind their recommendations for MIS surgery in CRC emergencies, whilst highlighting the challenges to implementation and the strategies to overcome them.

Core Tip: The management of colorectal cancer in the emergency setting presents distinct challenges. Despite its merits, the applicability of minimally invasive surgery in the emergency setting is limited by factors such as compromised patient physiology, resource constraints, and the need for technical expertise. We discuss our approaches to various colorectal emergencies, critically evaluating available literature, examining the challenges and strategies to overcome them with the goal of increasing minimally invasive surgery penetrance in the management of these conditions.

- Citation: Wong NW, Jabbar SAA, Ngu JCY, Teo NZ. Minimally invasive surgery for colorectal cancer emergencies. World J Clin Oncol 2025; 16(8): 107757

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v16/i8/107757.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v16.i8.107757

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignancies worldwide[1]. The benefits of minimally invasive surgery (MIS), defined in this article as laparoscopic or robotic-assisted surgery, in the elective management of CRC are well established[2-4]. Recent studies have also shown a reduction in postoperative morbidity and mortality, in addition to a shorter length of stay (LOS) when an MIS approach is adopted for emergency colorectal surgery[5-7]. While major guidelines have shifted their recent recommendations to favor a MIS laparoscopic approach for emergency cases[8,9], the evidence has largely been retrospective, with criticisms pertaining to selection bias in an emergency setting (i.e. younger and fitter patients are more likely to undergo laparoscopic surgery compared to their elderly counterparts).

In addition, barriers remain in the adoption of MIS in the emergency setting, such as suboptimal patient physiology precluding safe pneumoperitoneum, protracted operating time, resource constraints, and the lack of trained staff outside of working hours. With approximately one-third of all CRCs presenting to hospitals as an emergency[1,10,11], either with obstruction, perforation, or bleeding, there is a need to examine the challenges and evaluate strategies to increase the adoption of MIS in the emergency management of CRC.

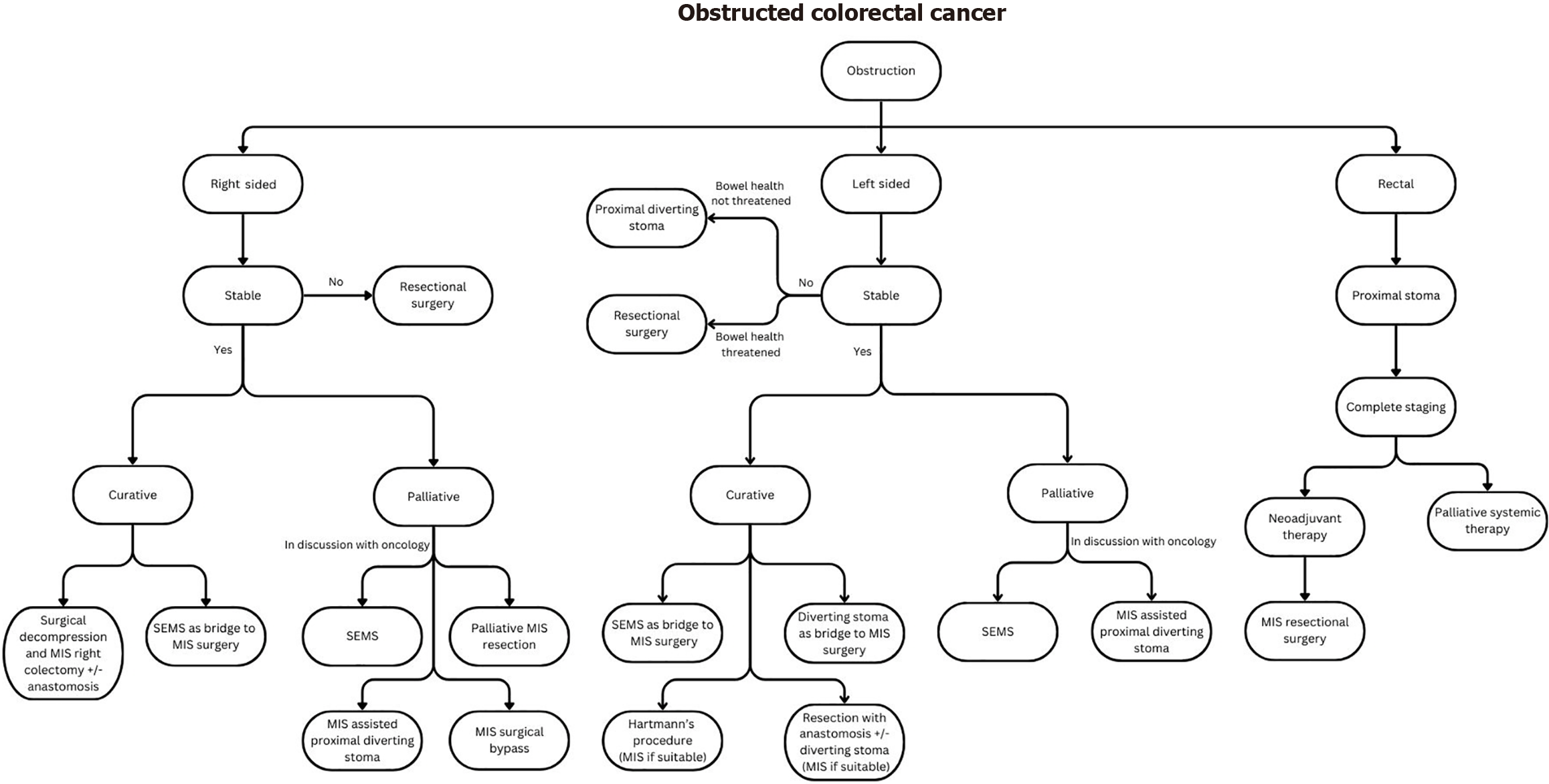

The most common presentation of CRC in the emergency setting is large bowel obstruction (up to 80% of all cases)[1,11] and its management remains a challenge when considering multiple patient and disease factors coupled with the multitude of treatment options available. Key factors to consider in deciding on the best patient-tailored therapy include that of: (1) Management intent (curative vs palliative); (2) Site of tumor; (3) Hemodynamic stability of the patient and ability to tolerate pneumoperitoneum; (4) Patient’s age and physiology (i.e. American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] physical status and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status); and (5) Expertise of the clinician and/or institution in MIS or advanced endoscopic techniques.

The management options include self-expandable metallic stents (SEMS), proximal diversion or resectional surgery with or without anastomosis and covering stoma. The choice of approach should be individualized based on the aforementioned factors. This group of patients can be broadly classified into three groups: (1) Patients who should be palliated; (2) Patients who would benefit from decompression as a bridge to definitive surgery; and (3) Patients who require upfront resectional surgery.

Patients who should be considered for palliation are those who present with synchronous unresectable metastases, or those who have localized disease but are too frail to undertake surgery. In the setting of an obstructed colon cancer, a multidisciplinary team discussion that includes the medical oncologist should be held to discuss the patient’s tumor biology, suitability for potential conversion, and prognosis. This influences the decision for palliative SEMS or diverting stoma in view of the risk of bevacizumab-associated colonic perforation with SEMS. For those patients with a short life expectancy and those unlikely to receive chemotherapy, SEMS is the preferred choice as it is associated with shorter hospital LOS, lower ostomy rates and better quality of life[2]. For obstructed rectal cancer, where SEMS is contraindicated, a palliative diverting stoma should be the primary management strategy.

A laparoscopic approach should be undertaken when performing a diverting stoma[12]. Available evidence suggests that associated morbidity and mortality are lower than open surgical techniques, with faster patient recovery[12,13]. If patient physiology and technical factors permit, laparoscopic assisted stoma creation is the authors’ preferred choice, as it ensures accurate localization, orientation and mobilization of bowel for stoma creation.

For patients with right-sided colon cancer and deemed not suitable for stenting, palliative MIS resection with or without an anastomosis should be considered, especially in the context of a competent ileocecal valve, which precludes suitability for proximal diversion. Due to its retroperitoneal anatomy, performing an ascending colostomy in such a situation would be technically challenging. In the context of an incompetent ileocecal valve, a palliative ileostomy or surgical bypass are possible options. Best supportive care with management inputs from a palliative specialist is an alternative to the above options. Ultimately, treatment should be individualized with shared decision making with the patient.

Bridging to definitive surgery or bridge-to-surgery (BTS) aims to relieve the acute issue of obstruction either with a diverting stoma or SEMS[14] before definitive surgery. This approach averts high-risk emergency surgery and provides time for patient optimization and bowel decompression. Importantly, this also allows the adoption of MIS for elective definitive surgery and increases primary anastomosis (RPA) rates. Patients who benefit include those with localized disease and those with resectable metastases.

The role of SEMS as a BTS has evolved since initial concerns of poor long term oncological outcomes from micro perforations[15]. This is reflected in recent guidelines from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, supporting the use of SEMS as a suitable alternative to upfront emergency surgery in left-sided malignant colonic obstruction[2,16] – a revision from prior recommendations, which advocated that its use be limited to high-risk patients or those for palliation[17]. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis conducted in 2020 of 3894 patients from 27 studies found that the use of SEMS as a BTS in curative cases resulted in improved short-term surgical outcomes with higher rates of RPA, decreased postoperative complications, lower 30-day mortality, decreased intensive care unit (ICU) days and hospital LOS with similar long term oncological (3-year and 5-year disease-free survival [DFS]) and survival outcomes[18]. This further substantiates the benefits of SEMS and addresses oncological concerns with its placement. The risk of bias for the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were evaluated as per Cochrane Collaboration guidelines and selection of high quality non-RCTs were performed with a validated scoring system (methodological index for non-randomized studies instrument) as part of the quality assessment.

Evidence for the role of SEMs as a BTS in the management of right-sided colonic obstruction has also evolved to challenge the traditional dogma of upfront emergency resection. A recent meta-analysis of 5136 patients showed a reduction in postoperative complication and mortality, coupled with greater use of a laparoscopic approach when SEMS is used as a BTS[19]. The use of SEMS for the above indication is reflected in the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons 2022 and European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2020 guidelines.

Nevertheless, SEMS is not without its risk of complications including that of perforation, stent migration, technical failure and re-occlusion. Key factors affecting complication rates include the degree of occlusion, length and location of tumor, and operator experience[20]. Success with this procedure, requires appropriate patient selection, a clear un

Given the evidence, SEMS appears to be the first choice as a BTS. This is especially in the setting of a patient at higher risk of postoperative complication after emergency surgery (> 70-year-old and/or ASA > II), as per European Society for Medical Oncology guidelines[21]. However, a diverting stoma remains an alternative BTS option in cases where technical expertise is not available; SEMS failure occurs; challenging anatomy precludes SEMS deployment (e.g., flexural areas, complete luminal obstruction); there is an obstructed rectal cancer, and in CRC patients with resectable metastases requiring neoadjuvant therapy. Tan et al[22] performed a systematic review and network meta-analysis which found that SEMS and decompressing stoma strategies as a BTS was associated with better 5-year overall survival and DFS rates than upfront emergency resection for left-sided obstructed CRC.

When performing a diverting stoma, the decision regarding its site should take into consideration the eventual plan for resection and whether a protective stoma is required. If no protective stoma is required during the definitive resection, the stoma should be sited within the planned resection zone to minimize the number of eventual anastomoses. However, if required, it may be sited to serve as a defunctioning stoma after definitive surgery (e.g., proximal loop transverse colostomy for obstructed rectal cancer planned for low anterior resection after neoadjuvant therapy).

For patients presenting with obstructing rectal cancer, SEMS is not an option for management due to its associated risk of chronic pain, tenesmus[23], and potential insufficient distal landing zone for safe SEMS placement. A diverting stoma is therefore the management of choice which allows time for adequate staging and initiation of neoadjuvant therapy before definitive surgery.

Upfront resectional surgery should be reserved for patients with: (1) Threatened bowel; (2) Right sided lesions not amenable to stenting; (3) Stent related complications such as perforation; and (4) Those who decline staged surgery with BTS options. The planned resection margins should include an oncological resection of the obstructed tumor and any non-viable bowel. For left-sided obstructing colon cancer, a subtotal or total colectomy may be performed in situations if there is a long segment of non-viable bowel proximal to the primary malignancy. When the length of non-viable bowel is short and a significant distance away from the primary tumor, an alternative to a subtotal colectomy is to resect separately before deciding on suitability for anastomosis of each resected portion.

Where upfront surgery is considered in left-sided cancers, the decision to perform a Hartmann’s procedure vs resection with RPA with or without a diverting stoma should factor: (1) The patient’s surgical risk and hemodynamics; (2) Technical difficulty and morbidity of surgery; (3) Intra-operative findings – degree of contamination and tissue quality; and (4) Technical expertise of surgeon. Kube et al[24] retrospectively compared the different operative approaches for obstructed left colonic cancer and found no difference in morbidity or mortality between patients who underwent Hartmann’s procedure compared to resection with RPA and covering stoma. However, patients who underwent Ha

Where upfront surgery is considered in right-sided cancers with significantly dilated proximal bowel loops that precludes safe laparoscopy, initial bowel decompression at the intended proximal transection site can be performed extracorporeally before proceeding with laparoscopic right hemicolectomy.

A laparoscopic first approach should be attempted if suitable, taking into account the patient’s physiology, resectability of the cancer and available surgical expertise[25], and has been shown to be associated with better short term surgical outcomes, increased 3-year overall survival and DFS with similar 90-day mortality when compared to an open approach[26]. A multicenter RCT by Harji et al[27] also showed feasibility of a laparoscopic approach with benefits of lower morbidity and shorter LOS in this group of patients. As such, the recent Cesena guidelines by the World Society of Emergency Surgery[8] recommends the use of laparoscopy as the initial approach for stable patients with colorectal emergencies. Based on the afore-mentioned considerations, coupled with the primary consideration of patient’s physiology (hemodynamic stability), our management algorithm for obstructed CRC with the goal of achieving MIS surgery (be it primary or in a staged fashion) is summarized in Figure 1.

Challenges in performing MIS for emergency CRC can be broadly classified into patient factors, surgeon factors, institution/resource factors, and intra-operative factors. Of these, intra-operative technical challenge remains one of the commonly cited reasons for conversion to open surgery, even in the elective setting of colorectal surgery[28,29].

For stable patients who can tolerate pneumoperitoneum, surgeons are often faced with the technical challenge of a lack in working space secondary to distended bowel loops. This results in suboptimal exposure of the target anatomy and reduces the margin for error in performing safe laparoscopic dissection. Distended bowel loops further increase the risks of inadvertent injuries by being in the path of insertion of the laparoscopic instruments, making access to the target anatomy even more challenging. Failure to recognize key anatomical landmarks, poor access to the area of dissection can result in inadvertent injuries and conversions to open surgery. Strategies to achieve MIS surgery are therefore focused on dealing with these particular challenges, of which some strategies the authors propose are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 2.

| Challenges | Mitigation strategies |

| Limited working space | Consider proximal decompression at site of intended proximal transection |

| e.g., in the case of right-sided cancer with significantly dilated small bowel loops from an incompetent ileocecal valve, an extended periumbilical incision can be made to first perform decompression via a controlled enterotomy extracorporeally at the site of the planned proximal transection (Figure 2), before proceeding with MIS surgery | |

| Use gauzes to pack small bowel away and minimize accidental thermal injury to surrounding structures | |

| Limited exposure | Adjust patient’s positioning to displace distended bowel away and maximize exposure |

| (Consider the use of a surgical table with greater articulating range and patient secured to the table with a surgical bean-bag) | |

| Limited access to target anatomy | Work from different approaches (lateral/medial/inferior/supra-colic) and extrapolate from known planes |

| Perform dissection distal to obstruction where tissue planes are normal with collapsed bowel. Subsequently perform early distal bowel transection to gain better exposure, before working more proximally |

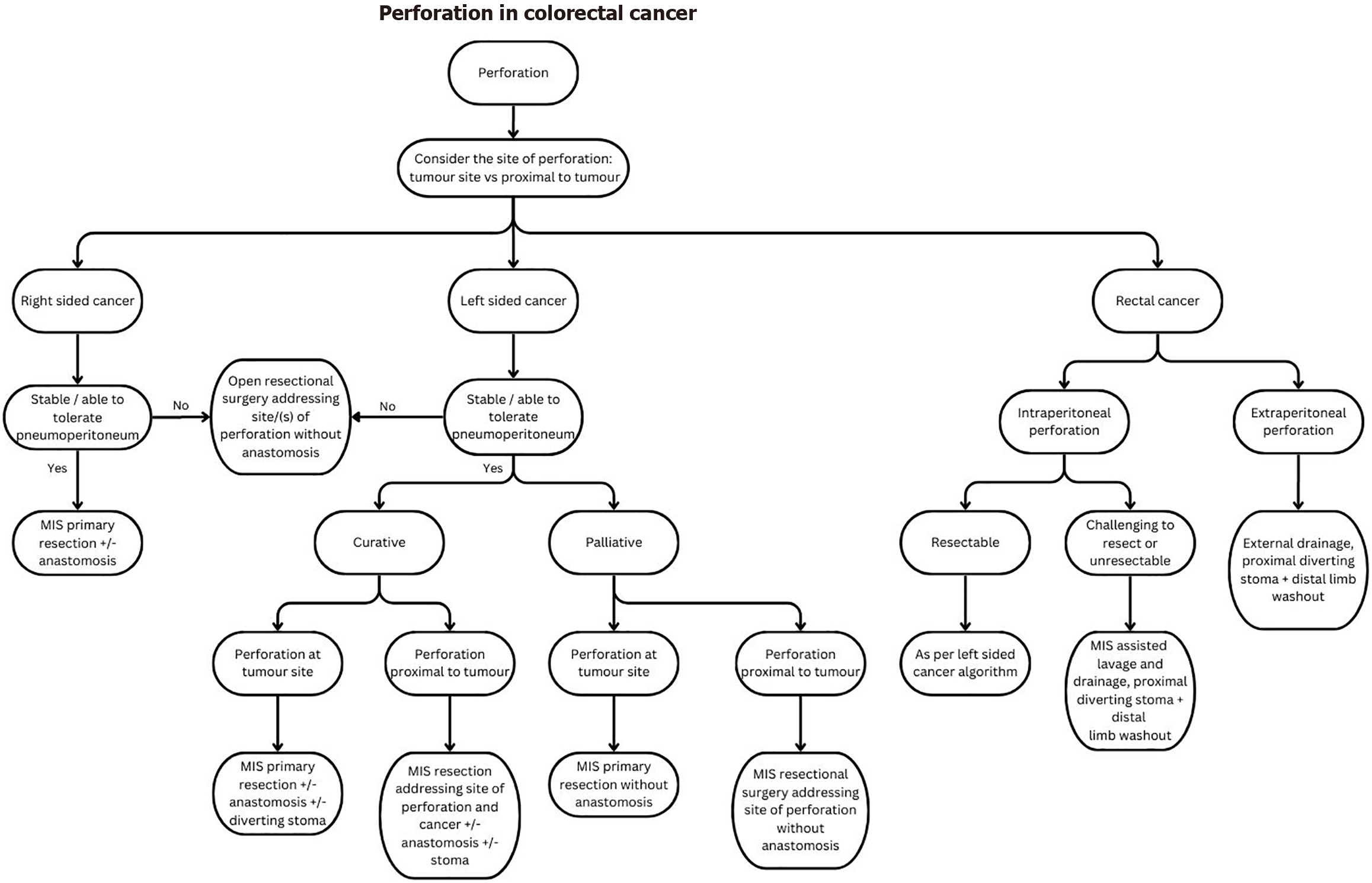

Perforation is the second most common emergency presentation of CRC and can occur either at the tumor site (70% of cases) or proximal to it (30% of cases)[1]. Prompt recognition and timely surgical intervention for source control is essential to mitigate the high morbidity and mortality associated with septic shock, especially in uncontained perforations.

Key factors to consider in deciding on the best patient-tailored therapy include: (1) Management intent (curative/palliative); (2) Hemodynamic stability of the patient; (3) Degree of contamination and whether the perforation is con

Right-sided colon cancer: Patients with right-sided perforated colon cancer will require a right hemicolectomy to address the site of perforation for source control. In most situations, a primary ileocolic anastomosis is performed[30]. However, this decision should consider the degree of contamination, intraoperative bowel quality, and the patient’s preoperative and intraoperative physiology. It is important to keep in mind that an anastomotic leak would result in a delay to chemotherapy and risk of systemic dissemination of disease in addition to the risk of morbidity and mortality[31].

Damage control surgery aimed at reducing surgical operative time should be considered in patients who are unstable or with poor physiological reserves[1]. This entails resectional surgery and washout for the first surgery with temporary abdominal wall closure, resuscitating the patient in the ICU before a staged second surgery to reestablish GI continuity and close the abdominal wall.

Left-sided CRC: The site of perforation and location of tumor must be considered when deciding on the type of surgery for left-sided CRC. Surgical options include that of: (1) Resection without RPA such as the Hartmann’s procedure; (2) Resection with RPA without diverting stoma; and (3) RPA with diverting stoma and distal limb washout. Evidence on the choice of surgical approach are extrapolated from evidence relating to the management of perforated diverticulitis.

Breitenstein et al[32] found in their case-matched control study of 110 patients that RPA with diverting ileostomy was a superior treatment to Hartmann’s procedure in acute left-sided colon perforation in view of the higher rates of stoma reversals and that, in the absence of feculent peritonitis, an ileostomy appeared unnecessary. The quoted anastomotic leak rate was 13% in the RPA without stoma group.

Oberkofler et al[33] substantiated this in their multicenter RCT of 62 patients with Hinchey III or IV acute diverticulitis, favoring RPA with diverting ileostomy over Hartmann’s procedure in terms of stoma reversal outcomes by showing that ileostomy reversal was more likely to occur (90% vs 57%; P = 0.005) and associated with less severe complications than a colostomy reversal after Hartmann’s Procedure.

The multicenter, randomized superiority LADIES trial by Lambrichts et al[34] in 2019, which is the largest RCT on this topic to date, showed a significantly better 12-months stoma-free-survival for the RPA group (94.6% for RPA vs 71.7% for Hartmann’s procedure, hazard ratio = 2.79), with no difference in short term morbidity and mortality for the index procedures. They concluded that in hemodynamically stable, immunocompetent patients younger than 85 years, RPA with or without diverting stoma is preferred to Hartmann’s procedure as a treatment for perforated diverticulitis (Hinchey III or Hinchey IV disease). The 3-year follow-up data continued to show benefit for the RPA group with better 36-month stoma-free-survival rates, lower rates of parastomal hernias and lower rates of hospitalizations[35].

More recently, the prospective, international, multicenter, observational, “Goodbye Hartmann trial”[36] published in 2024 of 1215 patients recommended that RPA with or without diverting stoma be considered the surgical standard and Hartmann’s procedure to be left for exceptional cases. On logistic regression for factors influencing the decisions for either surgical option, they found RPA to be preferred in patients who were younger, had low ASA score (≤ 3), had absence of colonic ischemia, and performed by a surgeon with experience in at least 50 colorectal resections. The above factors reflect the reality of selection bias in emergency colorectal practice, where patients with higher surgical risks or emergency surgeries performed out of office hours in non-experienced hands, are more likely to undergo a Hartmann’s procedure.

Of note, the studies by Breitenstein et al[32], Oberkofler et al[33] and Lambrichts et al[34] all showed similar morbidity and overall complications in the index operation for both the RPA with or without diverting stoma and Hartmann’s procedure groups. The main benefit of RPA therefore relates to long term stoma-free-survival and reduced stoma related complications. For patients who are hemodynamically unstable with poor physiological reserves, the Hartmann’s procedure, which has a shorter operative time, is still very much relevant.

In terms of evidence on the utility of MIS in colorectal perforations, literature largely stems from the management of benign perforations such as acute diverticulitis or iatrogenic colorectal perforations. Retrospective cohorts with a mix of both benign and malignant etiologies have shown the benefit of the laparoscopic approach in reducing surgical site infections with no difference in overall morbidity and mortality[37,38].

Extrapolating from evidence on perforated diverticulitis regarding the use of a laparoscopic approach in performing a Hartmann’s procedure or resection with RPA from a database of > 4000 propensity score matched patients, Monzavi et al[39] found that laparoscopic resection with RPA was associated with longer operative times. However, when compared to an open approach, there were lower rates of wound complications, sepsis, morbidity and shorter LOS, without differences in anastomotic leak rates or mortality. The same study found that laparoscopic Hartmann’s procedure was associated with longer operative times than an open approach but lower rates of respiratory failure, without differences in morbidity, mortality or LOS. Although contemporary evidence suggests that MIS colorectal resections confer some short-term benefits, surgical decisions on approach should be individualized, taking into account patient factors, operative findings and the surgical expertise available.

Rectal cancer: The management of rectal cancer perforation depends on its site. Intraperitoneal perforations can cause significant peritonitis and are managed as per left-sided colonic perforations. For extraperitoneal mid to low rectal cancers where the lesion is challenging to resect, emergency proctectomy is associated with significant operative time, a higher risk of bleeding and injury to the nerves of the pelvic floor, bladder, and genitalia[40] and should generally be avoided. Instead, adequate drainage, proximal diverting stoma with distal limb washout should be considered in the emergency setting as a bridge to elective resectional surgery. If drainage is performed, the site of drainage (or per

Challenges that pertain to perforated CRC include: (1) The lack of sufficient working space due to bowel distension secondary to paralytic ileus; (2) Challenging surgical anatomy due to less obvious anatomical planes, the presence of a bulky lesion, limited exposure to identify key structures, and active inflammation of tissues (especially in the presence of an inflammatory phlegmon); (3) Poor optics relating to plume generation from cautery over inflamed or edematous tissue; (4) Concerns on MIS ability for adequate lavage and decontamination; (5) Tissue quality (distended edematous bowel, inflamed friable tissues) which increases the risk of iatrogenic injury; and (6) Controlling further intraoperative spillage from the site of perforation. We share some suggested strategies to address these in Table 2.

| Challenges | Mitigation strategies |

| Limited working space, exposure and access to target anatomy | As per Table 1 |

| Difficulty in identifying critical structures and less obvious anatomical planes | Extrapolating from normal tissue planes and known anatomy – there may be a need to start dissection away from the target pathology to identify normal anatomical structures first, before working back towards the pathology by extrapolating from known tissue planes |

| Use of adjuncts such as use of lighted ureteric stents or indocyanine green can be helpful | |

| Poor optics from surgical smoke and plume generation | Use of intraoperative smoke evacuation systems, or continuous smoke evacuation and carbon dioxide recirculation devices (e.g., AirSeal iFS [CONMED Corp., Largo, FL United States]) to provide more stable pneumoperitoneum pressures and faster clearance of plume |

| Reduction of plume generation by keeping dissection planes dry with gauze and frequent suctioning | |

| Concerns of adequate decontamination/Lavage in contaminated cases | Use gravity to bring contaminated fluid to more accessible areas with systematic changes to patient positioning |

| Use of laparoscopic gauze as a wick when performing suctioning in regions that are harder to gain full exposure | |

| Consider the use of laparoscopic suction/irrigation powered pump devices to improve surgical efficiency | |

| Friable and inflamed tissue | Heighten awareness on tactile and visual feedback when handling tissues to avoid excessive traction |

| Distributing force applied on tissues over a larger surface area by pushing tissues with an open grasper or using a gauze to aid in this. Avoid direct grasping or pulling of tissues as this can easily result in inadvertent injuries | |

| Inflamed tissues are more susceptible to bleeding. Performing meticulous hemostasis at all times during the surgery to keep planes dry | |

| Control of further intraoperative spillage | Proximal control with laparoscopic bulldog clamp to prevent continued downstream contamination |

| Pack defect with gauze | |

| If tissue quality is suitable, perform primary closure of the site of perforation as a temporizing measure if added operative time is short |

Bleeding is a common presentation of CRC but is usually slow in nature and self-limiting[41]. Its acute presentation in the emergency setting of CRC tends to be rare. In such situations, the treatment of choice would be that of endoscopic treatment[42] or angioembolization. Should emergent surgery be necessary, a MIS approach is recommended with an additional consideration to perform vascular control and ligation first to control further blood loss.

Robotic-assisted surgery in elective MIS colorectal surgery is gaining traction with its ability to address the technical and ergonomic shortcomings of laparoscopic surgery. Evidence on its use in the emergency setting for colorectal surgery is still in its infancy and has been limited to early experiences from a few institutions[43-45]. Resource constraints, logistical challenges, and cost concerns pose significant barriers to its adoption in the emergency setting.

Despite this, there is growing acceptance[46] and interest in this topic, which has prompted the World Society of Emergency Surgery to publish a position paper in 2021 outlining guidance on specific situations in which robotic approaches may be preferred[47]. Robotic systems, with its capability of stable 3D stereoscopic vision, fully articulating wristed instruments, stable instruments with movement scaling and tremor filtration, are well suited to address some of the intraoperative challenges of emergency CRC surgery and may reduce the risk of conversions[47]. Its limitation when compared to laparoscopy is the inability to perform multi-quadrant surgery without the need to re-dock should contamination be extensive.

One of the early published studies on the use of robotic surgery in the management of emergency colorectal malignancy is a small series of four cases of malignant bowel obstructions and six benign colorectal conditions by Maertens et al[45], which found potential benefits of better radical lymph node dissection and reduced need for diverting stoma with robotic assisted surgery. Curfman et al[48] compared open, laparoscopic, and robotic approaches for the management of emergency colorectal resections in acute diverticulitis retrospectively. They found a reduction in ICU admission rates and anastomotic leak rates when robotic surgery was used compared to an open approach. When robotic surgery was compared with laparoscopic surgery, it was associated with reduced anastomotic leak rates and conversion rates to open surgery. However, robotic surgery was associated with longer intraoperative times.

Lunardi et al[46] analyzed temporal trends in MIS emergency surgery for common general surgical conditions as a secondary outcome in a recent retrospective cohort study using data from a claims registry of 89098 emergency colectomies of all surgical approaches (open, laparoscopic, robotic-assisted) between 2013 and 2021. The results demonstrated that, when compared to laparoscopic surgery, robotic-assisted surgery was associated with a significantly lower risk of conversion to open (odds ratio = 0.37) and shorter postoperative LOS (-0.48 days) after propensity score matching between the 2 MIS approaches (3375 patients in each group). The critique for this study is its relatively high conversion rate of 25.5% in the laparoscopic colectomy group which may indicate poor patient selection or insufficient surgical experience. However, this study showed a significant shift in current trends towards robotic-assisted surgery for emergency colectomies over the years (from 1.4% in 2013 to 8.8% in 2021, 0.9% increase per year, with a two-fold increase in numbers in the final 3 years of the study), providing us a projected trajectory of the future of emergency colorectal surgery. The ROEM prospective, multicenter international study[49] which recently published its trial protocol, aims to assess the safety, feasibility and cost-effectiveness of robotic-assisted benign emergency surgery and we await its future results. Patient selection remains key and, as robotic-assisted surgery becomes more prevalent, barriers to its im

Evidence is maturing on the utility of MIS in the management of emergency CRC surgery. Despite longer operative times, MIS has been shown to be safe and feasible with improved short-term outcomes. Patient selection remains key to its successful adoption and important factors include that of overall management intent (curative/palliative), site of pathology and patient’s hemodynamic status.

MIS is technically challenging and should be performed by experienced surgeons who have mounted their learning curve for MIS elective colorectal resections as per National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines. The use of robotics in emergency colorectal surgery is evolving and shows promise with lower rates of conversion and shorter LOS by addressing certain limitations of laparoscopic surgery. Future prospective studies should be directed at addressing the utility of robotic emergency oncological surgery. With continued advancements and adoption of MIS techniques, the potential to improve patient outcomes in emergency CRC management is significant.

| 1. | Pisano M, Zorcolo L, Merli C, Cimbanassi S, Poiasina E, Ceresoli M, Agresta F, Allievi N, Bellanova G, Coccolini F, Coy C, Fugazzola P, Martinez CA, Montori G, Paolillo C, Penachim TJ, Pereira B, Reis T, Restivo A, Rezende-Neto J, Sartelli M, Valentino M, Abu-Zidan FM, Ashkenazi I, Bala M, Chiara O, De' Angelis N, Deidda S, De Simone B, Di Saverio S, Finotti E, Kenji I, Moore E, Wexner S, Biffl W, Coimbra R, Guttadauro A, Leppäniemi A, Maier R, Magnone S, Mefire AC, Peitzmann A, Sakakushev B, Sugrue M, Viale P, Weber D, Kashuk J, Fraga GP, Kluger I, Catena F, Ansaloni L. 2017 WSES guidelines on colon and rectal cancer emergencies: obstruction and perforation. World J Emerg Surg. 2018;13:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vogel JD, Felder SI, Bhama AR, Hawkins AT, Langenfeld SJ, Shaffer VO, Thorsen AJ, Weiser MR, Chang GJ, Lightner AL, Feingold DL, Paquette IM. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Colon Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65:148-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 63.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group; Nelson H, Sargent DJ, Wieand HS, Fleshman J, Anvari M, Stryker SJ, Beart RW Jr, Hellinger M, Flanagan R Jr, Peters W, Ota D. A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2050-2059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2606] [Cited by in RCA: 2518] [Article Influence: 119.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Colon Cancer Laparoscopic or Open Resection Study Group; Buunen M, Veldkamp R, Hop WC, Kuhry E, Jeekel J, Haglind E, Påhlman L, Cuesta MA, Msika S, Morino M, Lacy A, Bonjer HJ. Survival after laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: long-term outcome of a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:44-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 965] [Cited by in RCA: 1056] [Article Influence: 62.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Harji DP, Griffiths B, Burke D, Sagar PM. Systematic review of emergency laparoscopic colorectal resection. Br J Surg. 2014;101:e126-e133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chang J, Assouline E, Calugaru K, Gajic ZZ, Doğru V, Ray JJ, Erkan A, Esen E, Grieco M, Remzi F. Minimally invasive colectomies can be performed with similar outcomes to open counterparts for colorectal cancer emergencies: a propensity score matching analysis utilizing ACS-NSQIP. Tech Coloproctol. 2023;27:1065-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Vallance AE, Keller DS, Hill J, Braun M, Kuryba A, van der Meulen J, Walker K, Chand M. Role of Emergency Laparoscopic Colectomy for Colorectal Cancer: A Population-based Study in England. Ann Surg. 2019;270:172-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sermonesi G, Tian BWCA, Vallicelli C, Abu-Zidan FM, Damaskos D, Kelly MD, Leppäniemi A, Galante JM, Tan E, Kirkpatrick AW, Khokha V, Romeo OM, Chirica M, Pikoulis M, Litvin A, Shelat VG, Sakakushev B, Wani I, Sall I, Fugazzola P, Cicuttin E, Toro A, Amico F, Mas FD, De Simone B, Sugrue M, Bonavina L, Campanelli G, Carcoforo P, Cobianchi L, Coccolini F, Chiarugi M, Di Carlo I, Di Saverio S, Podda M, Pisano M, Sartelli M, Testini M, Fette A, Rizoli S, Picetti E, Weber D, Latifi R, Kluger Y, Balogh ZJ, Biffl W, Jeekel H, Civil I, Hecker A, Ansaloni L, Bravi F, Agnoletti V, Beka SG, Moore EE, Catena F. Cesena guidelines: WSES consensus statement on laparoscopic-first approach to general surgery emergencies and abdominal trauma. World J Emerg Surg. 2023;18:57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | de'Angelis N, Marchegiani F, Schena CA, Khan J, Agnoletti V, Ansaloni L, Barría Rodríguez AG, Bianchi PP, Biffl W, Bravi F, Ceccarelli G, Ceresoli M, Chiara O, Chirica M, Cobianchi L, Coccolini F, Coimbra R, Cotsoglou C, D'Hondt M, Damaskos D, De Simone B, Di Saverio S, Diana M, Espin-Basany E, Fichtner-Feigl S, Fugazzola P, Gavriilidis P, Gronnier C, Kashuk J, Kirkpatrick AW, Ammendola M, Kouwenhoven EA, Laurent A, Leppaniemi A, Lesurtel M, Memeo R, Milone M, Moore E, Pararas N, Peitzmann A, Pessaux P, Picetti E, Pikoulis M, Pisano M, Ris F, Robison T, Sartelli M, Shelat VG, Spinoglio G, Sugrue M, Tan E, Van Eetvelde E, Kluger Y, Weber D, Catena F. Training curriculum in minimally invasive emergency digestive surgery: 2022 WSES position paper. World J Emerg Surg. 2023;18:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Baer C, Menon R, Bastawrous S, Bastawrous A. Emergency Presentations of Colorectal Cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97:529-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jestin P, Nilsson J, Heurgren M, Påhlman L, Glimelius B, Gunnarsson U. Emergency surgery for colonic cancer in a defined population. Br J Surg. 2005;92:94-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hellinger MD, Al Haddad A. Minimally invasive stomas. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2008;21:53-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hollyoak MA, Lumley J, Stitz RW. Laparoscopic stoma formation for faecal diversion. Br J Surg. 1998;85:226-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Veld JV, Amelung FJ, Borstlap WAA, van Halsema EE, Consten ECJ, Siersema PD, Ter Borg F, van der Zaag ES, de Wilt JHW, Fockens P, Bemelman WA, van Hooft JE, Tanis PJ; Dutch Snapshot Research Group. Comparison of Decompressing Stoma vs Stent as a Bridge to Surgery for Left-Sided Obstructive Colon Cancer. JAMA Surg. 2020;155:206-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sloothaak DA, van den Berg MW, Dijkgraaf MG, Fockens P, Tanis PJ, van Hooft JE, Bemelman WA; collaborative Dutch Stent-In study group. Oncological outcome of malignant colonic obstruction in the Dutch Stent-In 2 trial. Br J Surg. 2014;101:1751-1757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | van Hooft JE, Veld JV, Arnold D, Beets-Tan RGH, Everett S, Götz M, van Halsema EE, Hill J, Manes G, Meisner S, Rodrigues-Pinto E, Sabbagh C, Vandervoort J, Tanis PJ, Vanbiervliet G, Arezzo A. Self-expandable metal stents for obstructing colonic and extracolonic cancer: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2020. Endoscopy. 2020;52:389-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 39.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | van Hooft JE, van Halsema EE, Vanbiervliet G, Beets-Tan RG, DeWitt JM, Donnellan F, Dumonceau JM, Glynne-Jones RG, Hassan C, Jiménez-Perez J, Meisner S, Muthusamy VR, Parker MC, Regimbeau JM, Sabbagh C, Sagar J, Tanis PJ, Vandervoort J, Webster GJ, Manes G, Barthet MA, Repici A; European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Self-expandable metal stents for obstructing colonic and extracolonic cancer: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2014;46:990-1053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Spannenburg L, Sanchez Gonzalez M, Brooks A, Wei S, Li X, Liang X, Gao W, Wang H. Surgical outcomes of colonic stents as a bridge to surgery versus emergency surgery for malignant colorectal obstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of high quality prospective and randomised controlled trials. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46:1404-1414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kanaka S, Matsuda A, Yamada T, Ohta R, Sonoda H, Shinji S, Takahashi G, Iwai T, Takeda K, Ueda K, Kuriyama S, Miyasaka T, Yoshida H. Colonic stent as a bridge to surgery versus emergency resection for right-sided malignant large bowel obstruction: a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:2760-2770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim DH, Lee HH. Colon stenting as a bridge to surgery in obstructive colorectal cancer management. Clin Endosc. 2024;57:424-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Argilés G, Tabernero J, Labianca R, Hochhauser D, Salazar R, Iveson T, Laurent-Puig P, Quirke P, Yoshino T, Taieb J, Martinelli E, Arnold D; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: clinicalguidelines@esmo.org. Localised colon cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1291-1305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 491] [Cited by in RCA: 805] [Article Influence: 161.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tan L, Liu ZL, Ran MN, Tang LH, Pu YJ, Liu YL, Ma Z, He Z, Xiao JW. Comparison of the prognosis of four different treatment strategies for acute left malignant colonic obstruction: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. World J Emerg Surg. 2021;16:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | You YN, Hardiman KM, Bafford A, Poylin V, Francone TD, Davis K, Paquette IM, Steele SR, Feingold DL; On Behalf of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Rectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63:1191-1222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 224] [Article Influence: 44.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kube R, Granowski D, Stübs P, Mroczkowski P, Ptok H, Schmidt U, Gastinger I, Lippert H; Study group Qualitätssicherung Kolon/Rektum-Karzinome (Primärtumor) (Quality assurance in primary colorectal carcinoma). Surgical practices for malignant left colonic obstruction in Germany. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2010;36:65-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. SAGES Guidelines for Laparoscopic Resection of Curable Colon and Rectal Cancer. [cited 28 March 2025]. Available from: https://www.sages.org/publications/guidelines/guidelines-for-laparoscopic-resection-of-curable-colon-and-rectal-cancer/. |

| 26. | Zwanenburg ES, Veld JV, Amelung FJ, Borstlap WAA, Dekker JWT, Hompes R, Tuynman JB, Westerterp M, van Westreenen HL, Bemelman WA, Consten ECJ, Tanis PJ; On behalf of the Dutch Snapshot Research Group. Short- and Long-term Outcomes After Laparoscopic Emergency Resection of Left-Sided Obstructive Colon Cancer: A Nationwide Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2023;66:774-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Harji DP, Marshall H, Gordon K, Twiddy M, Pullan A, Meads D, Croft J, Burke D, Griffiths B, Verjee A, Sagar P, Stocken D, Brown J; LaCeS Collaborators. Laparoscopic versus open colorectal surgery in the acute setting (LaCeS trial): a multicentre randomized feasibility trial. Br J Surg. 2020;107:1595-1604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Pandya S, Murray JJ, Coller JA, Rusin LC. Laparoscopic colectomy: indications for conversion to laparotomy. Arch Surg. 1999;134:471-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Masoomi H, Moghadamyeghaneh Z, Mills S, Carmichael JC, Pigazzi A, Stamos MJ. Risk factors for conversion of laparoscopic colorectal surgery to open surgery: does conversion worsen outcome? World J Surg. 2015;39:1240-1247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Otani K, Kawai K, Hata K, Tanaka T, Nishikawa T, Sasaki K, Kaneko M, Murono K, Emoto S, Nozawa H. Colon cancer with perforation. Surg Today. 2019;49:15-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tzivanakis A, Moran BJ. Perforated Colorectal Cancer. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2020;33:247-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Breitenstein S, Kraus A, Hahnloser D, Decurtins M, Clavien PA, Demartines N. Emergency left colon resection for acute perforation: primary anastomosis or Hartmann's procedure? A case-matched control study. World J Surg. 2007;31:2117-2124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Oberkofler CE, Rickenbacher A, Raptis DA, Lehmann K, Villiger P, Buchli C, Grieder F, Gelpke H, Decurtins M, Tempia-Caliera AA, Demartines N, Hahnloser D, Clavien PA, Breitenstein S. A multicenter randomized clinical trial of primary anastomosis or Hartmann's procedure for perforated left colonic diverticulitis with purulent or fecal peritonitis. Ann Surg. 2012;256:819-26; discussion 826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 249] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Lambrichts DPV, Vennix S, Musters GD, Mulder IM, Swank HA, Hoofwijk AGM, Belgers EHJ, Stockmann HBAC, Eijsbouts QAJ, Gerhards MF, van Wagensveld BA, van Geloven AAW, Crolla RMPH, Nienhuijs SW, Govaert MJPM, di Saverio S, D'Hoore AJL, Consten ECJ, van Grevenstein WMU, Pierik REGJM, Kruyt PM, van der Hoeven JAB, Steup WH, Catena F, Konsten JLM, Vermeulen J, van Dieren S, Bemelman WA, Lange JF; LADIES trial collaborators. Hartmann's procedure versus sigmoidectomy with primary anastomosis for perforated diverticulitis with purulent or faecal peritonitis (LADIES): a multicentre, parallel-group, randomised, open-label, superiority trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4:599-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Edomskis PP, Hoek VT, Stark PW, Lambrichts DPV, Draaisma WA, Consten ECJ, Bemelman WA, Lange JF; LADIES trial collaborators. Hartmann's procedure versus sigmoidectomy with primary anastomosis for perforated diverticulitis with purulent or fecal peritonitis: Three-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Int J Surg. 2022;98:106221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Perrone G, Giuffrida M, Abu-Zidan F, Kruger VF, Livrini M, Petracca GL, Rossi G, Tarasconi A, Tian BWCA, Bonati E, Mentz R, Mazzini FN, Campana JP, Gasser E, Kafka-Ritsch R, Felsenreich DM, Dawoud C, Riss S, Gomes CA, Gomes FC, Gonzaga RAT, Canton CAB, Pereira BM, Fraga GP, Zem LG, Cordeiro-Fonseca V, de Mesquita Tauil R, Atanasov B, Belev N, Kovachev N, Meléndez LJJ, Dimova A, Dimov S, Zelić Z, Augustin G, Bogdanić B, Morić T, Chouillard E, Bajul M, De Simone B, Panis Y, Esposito F, Notarnicola M, Lauka L, Fabbri A, Hentati H, Fnaiech I, Aurélien V, Bougard M, Roulet M, Demetrashvili Z, Pipia I, Merabishvili G, Bouliaris K, Koukoulis G, Doudakmanis C, Xenaki S, Chrysos E, Kokkinakis S, Vassiliu P, Michalopoulos N, Margaris I, Kechagias A, Avgerinos K, Katunin J, Lostoridis E, Nagorni EA, Pujante A, Mulita F, Maroulis I, Vailas M, Marinis A, Siannis I, Bourbouteli E, Manatakis DK, Tasis N, Acheimastos V, Maria S, Stylianos K, Kuzeridis H, Korkolis D, Fradelos E, Kavalieratos G, Petropoulou T, Polydorou A, Papacostantinou I, Triantafyllou T, Kimpizi D, Theodorou D, Toutouzas K, Chamzin A, Frountzas M, Schizas D, Karavokyros I, Syllaios A, Charalabopoulos A, Boura M, Baili E, Ioannidis O, Loutzidou L, Anestiadou E, Tsouknidas I, Petrakis G, Polenta E, Bains L, Gupta R, Singh SK, Khanduri A, Bala M, Kedar A, Pisano M, Podda M, Pisanu A, Martines G, Trigiante G, Lantone G, Agrusa A, Di Buono G, Buscemi S, Veroux M, Gioco R, Veroux G, Oragano L, Zonta S, Lovisetto F, Feo CV, Pesce A, Fabbri N, Lantone G, Marino F, Perrone F, Vincenti L, Papagni V, Picciariello A, Rossi S, Picardi B, Del Monte SR, Visconti D, Osella G, Petruzzelli L, Pignata G, Andreuccetti J, D'Alessio R, Buonfantino M, Guaitoli E, Spinelli S, Sampietro GM, Corbellini C, Lorusso L, Frontali A, Pezzoli I, Bonomi A, Chierici A, Cotsoglou C, Manca G, Delvecchio A, Musa N, Casati M, Letizia L, Abate E, Ercolani G, D'Acapito F, Solaini L, Guercioni G, Cicconi S, Sasia D, Borghi F, Giraudo G, Sena G, Castaldo P, Cardamone E, Portale G, Zuin M, Spolverato Y, Esposito M, Isernia RM, Di Salvo M, Manunza R, Esposito G, Agus M, Asti ELG, Bernardi DT, Tonucci TP, Luppi D, Casadei M, Bonilauri S, Pezzolla A, Panebianco A, Laforgia R, De Luca M, Zese M, Parini D, Jovine E, De Sario G, Lombardi R, Aprea G, Palomba G, Capuano M, Argenio G, Orio G, Armellino MF, Troian M, Guerra M, Nagliati C, Biloslavo A, Germani P, Aizza G, Monsellato I, Chahrour AC, Anania G, Bombardini C, Bagolini F, Sganga G, Fransvea P, Bianchi V, Boati P, Ferrara F, Palmieri F, Cianci P, Gattulli D, Restini E, Cillara N, Cannavera A, Nita GE, Sarnari J, Roscio F, Clerici F, Scandroglio I, Berti S, Cadeo A, Filippelli A, Conti L, Grassi C, Cattaneo GM, Pighin M, Papis D, Gambino G, Bertino V, Schifano D, Prando D, Fogato L, Cavallo F, Ansaloni L, Picheo R, Pontarolo N, Depalma N, Spampinato M, D'Ugo S, Lepre L, Capponi MG, Campa RD, Sarro G, Dinuzzi VP, Olmi S, Uccelli M, Ferrari D, Inama M, Moretto G, Fontana M, Favi F, Picariello E, Rampini A, Barberis A, Azzinnaro A, Oliva A, Totaro L, Benzoni I, Ranieri V, Capolupo GT, Carannante F, Caricato M, Ronconi M, Casiraghi S, Casole G, Pantalone D, Alemanno G, Scheiterle M, Ceresoli M, Cereda M, Fumagalli C, Zanzi F, Bolzon S, Guerra E, Lecchi F, Cellerino P, Ardito A, Scaramuzzo R, Balla A, Lepiane P, Tartaglia N, Ambrosi A, Pavone G, Palini GM, Veneroni S, Garulli G, Ricci C, Torre B, Russo IS, Rottoli M, Tanzanu M, Belvedere A, Milone M, Manigrasso M, De Palma GD, Piccoli M, Pattacini GC, Magnone S, Bertoli P, Pisano M, Massucco P, Palisi M, Luzzi AP, Fleres F, Clarizia G, Spolini A, Kobe Y, Toma T, Shimamura F, Parker R, Ranketi S, Mitei M, Svagzdys S, Pauzas H, Zilinskas J, Poskus T, Kryzauskas M, Jakubauskas M, Zakaria AD, Zakaria Z, Wong MP, Jusoh AC, Zakaria MN, Cruz DR, Elizalde ABR, Reynaud AB, Hernandez EEL, Monroy JMVP, Hinojosa-Ugarte D, Quiodettis M, Du Bois ME, Latorraca J, Major P, Pędziwiatr M, Pisarska-Adamczyk M, Walędziak M, Kwiatkowski A, Czyżykowski Ł, da Costa SD, Pereira B, Ferreira ARO, Almeida F, Rocha R, Carneiro C, Perez DP, Carvas J, Rocha C, Ferreira C, Marques R, Fernandes U, Leao P, Goulart A, Pereira RG, Patrocínio SDD, de Mendonça NGG, Manso MIC, Morais HMC, Cardoso PS, Calu V, Miron A, Toma EA, Gachabayov M, Abdullaev A, Litvin A, Nechay T, Tyagunov A, Yuldashev A, Bradley A, Wilson M, Panyko A, Látečková Z, Lacko V, Lesko D, Soltes M, Radonak J, Turrado-Rodriguez V, Termes-Serra R, Morales-Sevillano X, Lapolla P, Mingoli A, Brachini G, Degiuli M, Sofia S, Reddavid R, de Manzoni Garberini A, Buffone A, Del Pozo EP, Aparicio-Sánchez D, Dos Barbeito S, Estaire-Gómez M, Vitón-Herrero R, de Los Ángeles Gil Olarte-Marquez M, Gil-Martínez J, Alconchel F, Nicolás-López T, Rahy-Martin AC, Pelloni M, Bañolas-Suarez R, Mendoza-Moreno F, Nisa FG, Díez-Alonso M, Rodas MEV, Agundez MC, Andrés MIP, Moreira CCL, Perez AL, Ponce IA, González-Castillo AM, Membrilla-Fernández E, Salvans S, Serradilla-Martín M, Pardo PS, Rivera-Alonso D, Dziakova J, Huguet JM, Valle NP, Ruiz EC, Valcárcel CR, Moreno CR, Salazar YTM, García JJR, Micó SS, López JR, Farré SP, Gomez MS, Petit NM, Titos-García A, Aranda-Narváez JM, Romacho-López L, Sánchez-Guillén L, Aranaz-Ostariz V, Bosch-Ramírez M, Martínez-Pérez A, Martínez-López E, Sebastián-Tomás JC, Jimenez-Riera G, Jimenez-Vega J, Cuellar JAN, Campos-Serra A, Muñoz-Campaña A, Gràcia-Roman R, Alegre JM, Pinto FL, O'Sullivan SN, Antona FB, Jiménez BM, López-Sánchez J, Carmona ZG, Fernández RT, Sierra IB, de León LRG, Moreno VP, Iglesias E, Cumplido PL, Bravo AA, Simó IR, Domínguez CL, Caamaño AG, Lozano RC, Martínez MD, Torres ÁN, de Quiros JTMB, Pellino G, Cloquell MM, Moller EG, Jalal-Eldin S, Abdoun AK, Hamid HKS, Lohsiriwat V, Mongkhonsupphawan A, Baraket O, Ayed K, Abbassi I, Ali AB, Ammar H, Kchaou A, Tlili A, Zribi I, Colak E, Polat S, Koylu ZA, Guner A, Usta MA, Reis ME, Mantoglu B, Gonullu E, Akin E, Altintoprak F, Bayhan Z, Firat N, Isik A, Memis U, Bayrak M, Altıntaş Y, Kara Y, Bozkurt MA, Kocataş A, Das K, Seker A, Ozer N, Atici SD, Tuncer K, Kaya T, Ozkan Z, Ilhan O, Agackiran I, Uzunoglu MY, Demirbas E, Altinel Y, Meric S, Hacım NA, Uymaz DS, Omarov N, Balık E, Tebala GD, Khalil H, Rana M, Khan M, Florence C, Swaminathan C, Leo CA, Liasis L, Watfah J, Trostchansky I, Delgado E, Pontillo M, Latifi R, Coimbra R, Edwards S, Lopez A, Velmahos G, Dorken A, Gebran A, Palmer A, Oury J, Bardes JM, Seng SS, Coffua LS, Ratnasekera A, Egodage T, Echeverria-Rosario K, Armento I, Napolitano LM, Sangji NF, Hemmila M, Quick JA, Austin TR, Hyman TS, Curtiss W, McClure A, Cairl N, Biffl WL, Truong HP, Schaffer K, Reames S, Banchini F, Capelli P, Coccolini F, Sartelli M, Bravi F, Vallicelli C, Agnoletti V, Baiocchi GL, Catena F. Goodbye Hartmann trial: a prospective, international, multicenter, observational study on the current use of a surgical procedure developed a century ago. World J Emerg Surg. 2024;19:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Tanioka N, Kuwahara M, Maeda H, Edo N, Nokubo Y, Shimizu S, Akimori T, Seo S. Usefulness of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal perforation: a single-center retrospective cohort study. Surg Today. 2024;54:1301-1308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kudou K, Kusumoto T, Hasuda H, Tsuda Y, Kusumoto E, Uehara H, Yoshida R, Sakaguchi Y. Comparison of Laparoscopic and Open Emergency Surgery for Colorectal Perforation: A Retrospective Study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2023;33:464-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Esparza Monzavi CA, Naffouje SA, Chaudhry V, Nordenstam J, Mellgren A, Gantt G Jr. Open vs Minimally Invasive Approach for Emergent Colectomy in Perforated Diverticulitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2021;64:319-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Cima RR, Pemberton JH. Medical and surgical management of chronic ulcerative colitis. Arch Surg. 2005;140:300-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Wauters H, Van Casteren V, Buntinx F. Rectal bleeding and colorectal cancer in general practice: diagnostic study. BMJ. 2000;321:998-999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Pasha SF, Shergill A, Acosta RD, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Early D, Evans JA, Fisher D, Fonkalsrud L, Hwang JH, Khashab MA, Lightdale JR, Muthusamy VR, Saltzman JR, Cash BD. The role of endoscopy in the patient with lower GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:875-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Felli E, Brunetti F, Disabato M, Salloum C, Azoulay D, De'angelis N. Robotic right colectomy for hemorrhagic right colon cancer: a case report and review of the literature of minimally invasive urgent colectomy. World J Emerg Surg. 2014;9:32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Anderson M, Lynn P, Aydinli HH, Schwartzberg D, Bernstein M, Grucela A. Early experience with urgent robotic subtotal colectomy for severe acute ulcerative colitis has comparable perioperative outcomes to laparoscopic surgery. J Robot Surg. 2020;14:249-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Maertens V, Stefan S, Rawlinson E, Ball C, Gibbs P, Mercer S, Khan JS. Emergency robotic colorectal surgery during COVID-19 pandemic: A retrospective case series study. Laparosc Endosc Robot Surg. 2022;5:57-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Lunardi N, Abou-Zamzam A, Florecki KL, Chidambaram S, Shih IF, Kent AJ, Joseph B, Byrne JP, Sakran JV. Robotic Technology in Emergency General Surgery Cases in the Era of Minimally Invasive Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2024;159:493-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | de'Angelis N, Khan J, Marchegiani F, Bianchi G, Aisoni F, Alberti D, Ansaloni L, Biffl W, Chiara O, Ceccarelli G, Coccolini F, Cicuttin E, D'Hondt M, Di Saverio S, Diana M, De Simone B, Espin-Basany E, Fichtner-Feigl S, Kashuk J, Kouwenhoven E, Leppaniemi A, Beghdadi N, Memeo R, Milone M, Moore E, Peitzmann A, Pessaux P, Pikoulis M, Pisano M, Ris F, Sartelli M, Spinoglio G, Sugrue M, Tan E, Gavriilidis P, Weber D, Kluger Y, Catena F. Robotic surgery in emergency setting: 2021 WSES position paper. World J Emerg Surg. 2022;17:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Curfman KR, Jones IF, Conner JR, Neighorn CC, Wilson RK, Rashidi L. Robotic colorectal surgery in the emergent diverticulitis setting: is it safe? A review of large national database. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2023;38:142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Milone M, Anoldo P, de'Angelis N, Coccolini F, Khan J, Kluger Y, Sartelli M, Ansaloni L, Morelli L, Zanini N, Vallicelli C, Vigutto G, Moore EE, Biffl W, Catena F; ROEM Collaborative Group. The role of RObotic surgery in EMergency setting (ROEM): protocol for a multicentre, observational, prospective international study on the use of robotic platform in emergency surgery. World J Emerg Surg. 2024;19:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |