INTRODUCTION

According to recent global epidemiological data, gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer-related death[1,2]. The primary treatment for locally advanced gastric cancer involves radical surgery, including gastrectomy and D2 Lymph node dissection. However, for patients with unresectable advanced or metastatic gastric cancer, systemic therapy (such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy) is the standard treatment approach. Haematogenous metastasis from gastric cancer most commonly affects the liver, followed by the lungs and bones. Peritoneal implantation is also a common form of metastasis. While ovarian metastasis is less common, it represents a unique pattern of disease progression exclusive to female patients with gastric cancer[3]. The term “Krukenberg tumour” was first introduced by Friedrich Ernst Krukenberg in 1896 to describe ovarian metastases, particularly those originating from the stomach[4]. Previous reports have shown that Krukenberg tumours can arise from various primary sites, including the stomach, colon, breast, gallbladder, and appendix[5], although they most frequently originate from the stomach. Krukenberg tumours can exhibit diverse clinical manifestations and may be diagnosed either concurrently with primary gastric cancer (synchronous metastasis) or years after initial tumour resection (metachronous metastasis). Most Krukenberg tumours are bilateral. Additionally, the incidence of ovarian metastasis in women with unresectable or recurrent gastric cancer remains poorly defined, with some studies reporting ovarian metastasis rates of 0.3%-6.7% after radical resection and 33%-41% in postmortem findings[6,7]. Ovarian metastasis can occur via multiple routes, including lymphatic spread, haematogenous metastasis, direct invasion, and peritoneal seeding, although the precise mechanisms remain unclear[8]. Some studies have suggested that early lymphatic involvement in gastric cancer may facilitate ovarian metastasis, even in early-stage disease[9,10].

The prognosis of patients with ovarian metastasis from gastric cancer is influenced by several factors, including the characteristics of the primary tumour, the size of the metastatic lesions, the biological behaviour of the cancer cells, and the presence of concurrent multiple organ involvement or peritoneal seeding. Historically, ovarian metastasis in patients with gastric cancer has been considered a sign of advanced, incurable disease, with a median survival of 7-11 months[5]. Treatment for ovarian metastasis in patients with gastric cancer typically involves a multimodal approach. The recommended strategies often include radical gastrectomy, metastatic resection (such as total or partial hysterectomy combined with salpingo-oophorectomy or oophorectomy), radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and heated intraperitoneal chemoperfusion (HIPEC)[11-13].

SYSTEMIC TREATMENT

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy remains the standard treatment for patients with recurrent or metastatic advanced gastric cancer. However, due to the heterogeneity of ovarian metastases, the chemotherapy response rate in these patients is relatively low (ranging from 12% to 26%)[6]. Based on large-scale randomised controlled trials, first-line treatment typically involves a platinum-based regimen combined with fluorouracil, with options to include irinotecan, paclitaxel, or additional platinum. For second- and third-line treatments, the use of targeted therapies and immunotherapies has significantly improved the prognosis of patients with unresectable advanced gastric cancer[14-16]. Additionally, studies have shown that the chemotherapy regimen and the number of administered cycles are independently associated with treatment outcomes[7]. Specifically, most studies have suggested that the administration of more than four cycles of chemotherapy can improve the prognosis of gastric cancer patients with ovarian metastasis. However, the chemotherapy response of Krukenberg tumours is influenced by histological subtype and molecular characteristics. Histologically, the well-differentiated intestinal type according to Lauren's classification results in greater sensitivity to platinum-based regimens combined with fluorouracil, whereas the diffuse type results in a poorer response because of its pronounced invasiveness and elevated expression of drug resistance genes. At the molecular level, patients exhibiting human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) positivity may benefit from trastuzumab in conjunction with chemotherapy; conversely, TP53 mutations or MET amplification are associated with an increased risk of resistance to conventional chemotherapy. Precision treatment necessitates the integration of secondary biopsies from metastatic lesions alongside molecular profiling to optimize the selection of therapeutic regimens.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy for ovarian metastasis in gastric cancer primarily includes anti-HER2 treatment with trastuzumab and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (anti-VEGFR2) treatment with apatinib. Wang et al[17] reported that 4 out of 50 Krukenberg tumours were HER2-positive. Additionally, previous research has established a link between HER2 expression in primary gastric cancer and metastatic ovarian tumours[18]. For patients with HER2-positive cancers, trastuzumab combined with chemotherapy is recommended as the first-line therapy. Moreover, the ToGA trial (conducted in 2010) was the first study to demonstrate that the use of trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy can significantly improve survival[19]. Further data from the KEYNOTE-811 interim analysis indicated that the objective response rate for patients treated with trastuzumab plus chemotherapy for HER2-positive advanced gastric cancer increased by 22% when pembrolizumab was added to the regimen[20]. In addition to HER2-targeted therapies, antiangiogenic drugs such as apatinib have also demonstrated promise in the treatment of gastric cancer. Apatinib is a novel, low-molecular-weight tyrosine kinase inhibitor that selectively targets VEGFR2, thereby inhibiting tumour angiogenesis. The results of a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial involving 267 patients with advanced gastric cancer demonstrated that apatinib significantly improved median overall survival (OS) and prolonged median progression-free survival compared with the placebo group[21]. Trastuzumab combined with apatinib has demonstrated synergistic efficacy in the treatment of gastric cancer patients with ovarian metastasis. Clinical studies have shown that the objective response rate can be significantly increased in HER2-positive patients receiving trastuzumab in conjunction with chemotherapy. Apatinib improves antitumour angiogenesis by inhibiting VEGFR2, and this combination therapy can prolong progression-free survival while reducing adverse reactions[22]. With respect to the specific patterns of HER2-positive gastric cancer accompanied by ovarian metastasis, current research has not definitively elucidated the molecular mechanisms underlying this metastatic propensity. Nevertheless, HER2 overexpression may increase the risk of metastasis by facilitating cell invasion and promoting angiogenesis. In clinical trials such as the DESTINY-Gastric01 study, trastuzumab deruxtecan has achieved substantial responses in HER2-positive metastatic lesions; however, data pertaining to the ovarian metastasis subgroup remain limited. Therefore, further investigations are warranted to explore the relationships between molecular characteristics and the metastatic microenvironment[23].

Immunotherapy

For Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-positive patients, studies have shown that butyrate (when used as an inducer in combination with radiotherapy) can enhance tumour cell destruction and increase the expression of viral proteins, thereby activating immune-mediated tumour apoptosis[24-26]. Romidepsin, which is a Food and Drug Administration-approved histone deacetylase inhibitor, has been demonstrated to induce cell lysis in EBV-infected gastric cancer cells in vitro. When combined with proteasome inhibitors, this inhibitor can enhance the synergistic lethal effect on tumour cells[27,28]. Additionally, a case report demonstrated that avelumab was effective in treating EBV-positive gastric cancer with complete mismatch repair. In a small sample of six patients with advanced EBV-positive gastric cancer, the overall response rate (ORR) reached 100% after treatment with an immune checkpoint inhibitor[29]. However, this study was based on a small sample size. More patients need to be enrolled in the future to further supplement the data and verify the research conclusions. Moreover, the KEYNOTE-035-006 study revealed that the ORR of immunotherapy was 44.4%, with the 1-year OS being 83.3%, for patients with advanced gastric cancer and mismatch repair deficiency. Based on these findings, the Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines recommend the use of envafolimab for treating patients with advanced mismatch repair-deficient gastric cancer[30]. However, the immunogenicity of EBV-positive gastric cancer metastases in the ovaries may differ from that of the primary tumour due to microenvironmental heterogeneity and molecular evolution. Therefore, multisite molecular testing is essential for optimizing treatment strategies. Currently, there are no large-scale clinical studies specifically evaluating targeted therapies or immunotherapy in patients with advanced gastric cancer and ovarian metastasis. Future research is essential to further explore the mechanisms underlying ovarian metastasis in gastric cancer, as well as the development of drug resistance. Furthermore, more clinical studies are needed to continue improving the treatment landscape for ovarian metastasis in patients with gastric cancer.

Endocrine therapy

In women older than 50 years of age, oestrogen levels are typically low, with progesterone levels also beginning to decrease. Recent studies have suggested that oestrogen receptors may play a role in the development of gastric cancer, although most of the research on the role of the oestrogen receptor in cancer has historically focused on breast cancer[31]. Some studies have reported that sex hormones contribute to the development of gastric cancer, with high levels of oestrogen potentially increasing the risk of the disease[32]. Consequently, ovarian metastasis from gastric cancer is more common in premenopausal women younger than 50 years of age. In a study analysing risk factors for ovarian metastasis in 83 patients with gastric cancer, Li et al[33] identified several key factors associated with an increased risk of ovarian metastasis, including age ≤ 50 years, primary lymph node metastasis > 6, diffuse gastric cancer, and positive expression of oestrogen receptors. Furthermore, Yu et al[34] reported that increased expression of oestrogen and progesterone receptors was associated with improved prognosis in patients with ovarian metastasis from gastric cancer, thereby suggesting that endocrine therapy can be a potential treatment option for these patients.

HIPEC

HIPEC has been explored as a treatment option for Krukenberg tumours, although its efficacy remains inconclusive. Cheong et al[35] reported no significant difference in the efficacy between intravenous chemotherapy (IVT) and HIPEC in the treatment of Krukenberg tumours. In contrast, Rosa et al[36] reported that HIPEC combined with IVT resulted in longer median survival for patients with Krukenberg tumours compared with IVT alone. However, the inclusion criteria and treatment protocols for patients in the aforementioned two groups of studies were distinct, which may account for the discrepancies in their conclusions. Furthermore, some studies have suggested that HIPEC (when administered after tumour deactivation) can also prolong median survival in patients with Krukenberg tumours compared with deactivation alone. However, HIPEC is not recommended as a standalone treatment for patients who have not undergone tumour deactivation[37]. Although some scholars believe that translymphatic metastasis may be the primary mechanism underlying the formation of Krukenberg tumours in gastric cancer (with peritoneal seeding playing a less significant role), HIPEC may still offer clinical value. Given that Krukenberg tumours are frequently accompanied by ascites and diffuse peritoneal metastasis, this therapy could have important clinical applications and promising potential for further development.

Surgical treatment

Although an optimal treatment strategy for gastric cancer with Krukenberg tumours has not been established, aggressive approaches (including the resection of metastatic tumours) may improve the outcomes of these patients[6]. Ovarian metastasis in patients with gastric cancer typically occurs before menopause, and these patients generally demonstrate longer survival, thereby indicating that more aggressive treatment is a viable option. Ovarian metastases often undergo rapid growth, thus leading to symptoms involving abdominal and pelvic compression, such as hydronephrosis due to ureteral obstruction, difficulties in urinating and defecating, and abdominal or pelvic fluid accumulation. Surgical intervention can reduce the tumour burden and alleviate symptoms, thereby improving patients’ quality of life. For the overall affected population, although systemic chemotherapy is a standard treatment, its efficacy alone is limited. Given the restricted benefits of chemotherapy alone for survival, surgery has become increasingly important. Chemotherapy combined with targeted therapy or immunotherapy demonstrates promise as a conversion therapy for patients with gastric cancer and ovarian metastasis. Yan et al[38] reported that in 103 patients with gastrogenic Krukenberg tumours, OS was significantly longer in the metastatic resection group than in the nonresection group (18.9 months vs 12.4 months, respectively, P < 0.001). Similarly, Ma et al[39] reported that patients with gastric cancer and ovarian metastasis who underwent metastatic resection exhibited significantly longer OS than those who did not undergo resection (14 months vs 8 months, respectively; P = 0.001). A meta-analysis further supported these findings, thereby demonstrating that resection of ovarian metastatic tumours extended OS in these patients[40]. Another single-centre retrospective study also indicated that chemotherapy combined with metastasis resection significantly improved survival[34]. These studies suggested that resection of metastatic tumours may positively impact the prognosis of patients with Krukenberg tumours. However, all of the aforementioned studies were retrospective in nature, and the inclusion criteria for patients varied across each study, leading to certain potential biases. Consequently, further multicentre prospective studies are necessary to substantiate the benefits of surgical resection for ovarian metastases arising from gastric cancer. In general, larger metastases are associated with prolonged disease progression and fewer opportunities for early intervention, whereas smaller metastases are more amenable to R0 resection.

CLASSIFICATION AND COMPREHENSIVE TREATMENT OF OVARIAN METASTASIS IN GASTRIC CANCER

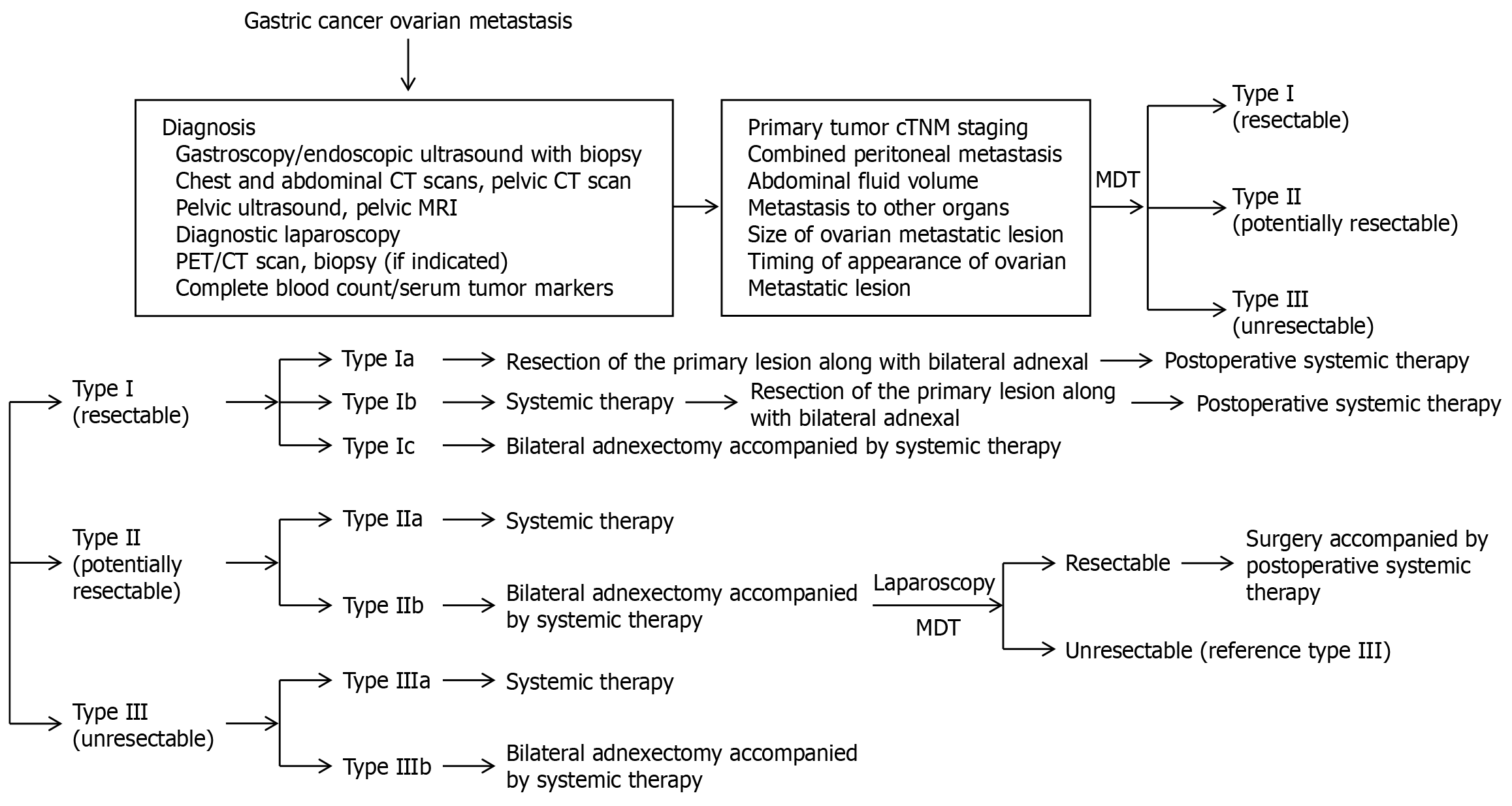

Based on extensive research, China has introduced the Chinese Expert Consensus on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Ovarian Metastasis from Gastric Cancer. This consensus outlines the Chinese Classification of Gastric Cancer with Ovarian Metastasis (known as the C-GCOM classification system) to guide the diagnosis and treatment of affected patients. This classification system aims to standardise the management of patients with ovarian metastasis, thereby providing clearer and more practical guidelines for clinicians. This system classifies ovarian metastasis in gastric cancer into three categories: Type I (resectable), Type II (potentially resectable), and Type III (unresectable). Moreover, this classification system supports more refined and individualised treatment strategies for patients with gastric cancer and ovarian metastasis (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The initial diagnostic and therapeutic approach for gastric cancer with ovarian metastasis.

CT: Computed tomography; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging; PET: Positron emission tomography; MDT: Multi-disciplinary team; TNM: Tumor-node-metastasis.

C-GCOM type I (resectable)

C-GCOM type I refers to gastric cancer complicated by simple ovarian metastasis. It is characterised by primary gastric cancer with a depth of invasion not exceeding T4a, resectable regional lymph nodes (D2 or D2+), no abdominal effusion, no signs of peritoneal metastasis or positive extraneous cytology, and no other organ metastasis. For patients with Type I ovarian metastasis, if the primary gastric tumour is limited to the mucosal layer or submucosa (T1), resection of both the primary gastric tumour and its adnexa may be an option, followed by systemic treatment (regardless of the size of the ovarian metastasis). In cases where the primary gastric tumour is T2 or higher and the ovarian metastasis is less than 5 cm in diameter, systemic treatment combined with resection of both the primary tumour and its adnexa may be considered. However, if the degree of ovarian metastasis is 5 cm or larger, systemic therapy should be prioritised after resection of the adnexa. Patients with this type of metastasis generally exhibit a better prognosis, and R0 resection is recommended for both primary and metastatic tumours. Moreover, radical gastrectomy with D2 Lymph node dissection is the preferred procedure for primary gastric tumours. For younger patients with initial unilateral ovarian metastasis, a contralateral ovarian biopsy is recommended to assess the possibility of ovarian preservation. If preservation is not feasible, prophylactic resection of the contralateral ovary should be performed, followed by postoperative systemic therapy.

C-GCOM type II (potentially resectable)

In patients with C-GCOM type II metastasis, the primary tumour typically exhibits a depth of invasion of T4b, with lymph nodes exhibiting bulky N2 characteristics. These patients may also exhibit cytological positivity, localised peritoneal metastasis [peritoneal metastasis index (PMI) ≤ 6], or other single-organ metastases. Conversion therapy is recommended based on comprehensive imaging, diagnostic laparoscopic exploration, and a multidisciplinary approach. For patients with ovarian metastases smaller than 5 cm and no significant symptoms (Type IIa), systemic therapy is the preferred treatment. However, for those patients with larger ovarian metastases (≥ 5 cm) or symptoms such as significant abdominal fluid accumulation (Type IIb), it is recommended to first perform metastatic resection to reduce tumour resistance before initiating systemic therapy, which may enhance the therapeutic effect. Systemic treatment for C-GCOM type II metastasis typically involves combination chemotherapy, with a two- or three-drug regimen being chosen based on the specific patient’s physical condition and tolerance. Single-agent chemotherapy is generally not recommended. Additionally, the development of molecular targeted therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors has expanded treatment options. Chemotherapy combined with anti-HER2 agents and immune checkpoint inhibitors has demonstrated a high response rate in advanced gastric cancer patients and offers a promising new approach for treating C-GCOM type II metastasis. Previous studies have suggested that, given that ovarian metastasis in gastric cancer is often accompanied by peritoneal metastasis, intraperitoneal chemotherapy or HIPEC may benefit patients with peritoneal involvement. These therapies should also be considered for patients with C-GCOM type II metastases. With respect to the duration of systemic treatment and the timing of surgical intervention, systemic treatment should generally continue for 3-6 months. Moreover, a comprehensive evaluation should be conducted every 2-3 cycles, with considerations of the efficacy of treatment, the patient’s physical condition, and the feasibility of surgery. Surgery should be performed when chemotherapy has been observed to be effective and resistance has not yet developed to ensure the best possible treatment outcomes. However, controversy exists regarding the scope of surgery, particularly with respect to the management of peritoneal metastasis. A multipoint biopsy or excision of lesions with limited peritoneal scarring is recommended to explore the best surgical options. Notably, even with radical tumour resection, Type II patients are still at increased risks of postoperative recurrence and metastasis. Therefore, postoperative systemic treatment should follow treatment protocols for advanced gastric cancer to improve both survival rates and quality of life.

C-GCOM type III (unresectable type)

In patients with C-GCOM type III metastases, the primary gastric tumour exhibits severe external invasion, which is often closely adjacent to peripheral tissues or surrounding large blood vessels, thereby leading to regional lymph node fixation, fusion, or extension beyond the scope of surgical resection. These patients may exhibit metastasis confined to the peritoneum (PMI ≤ 6) or widespread metastasis characterised by diffuse peritoneal metastasis (PMI > 6), which may or may not be accompanied by metastasis to other organs. Ovarian metastasis is classified based on size and symptoms. If the maximum diameter of the ovarian metastasis is less than 5 cm and there is no significant abdominal fluid or related symptoms observed, the patient is categorised as Type IIIa. However, if the ovarian metastasis reaches or exceeds 5 cm in diameter, is associated with a large amount of abdominal fluid, or causes significant symptoms, the patient is classified as Type IIIb. Type III patients typically present with more severe disease, which is often accompanied by extensive peritoneal metastasis or metastasis to other organs, thereby resulting in a poor prognosis. Treatment for these patients focuses on alleviating symptoms and prolonging survival, with an emphasis on encouraging participation in clinical trials. The treatment approach is similar to that for advanced gastric cancer, which primarily involves palliative care. For Type IIIb patients with large ovarian metastases, if the patient’s overall condition is favourable and the metastasis is not fixed or fused, adnexectomy may be initially considered to reduce the tumour burden and alleviate symptoms, followed by systemic therapy to improve the therapeutic effect.

CONCLUSION

Although the incidence of ovarian metastasis in patients with gastric cancer is relatively low, its prognosis is more severe than that of metastasis at other sites, thereby significantly impacting the treatment outcomes for female patients with gastric cancer. When considering the limited understanding of the mechanisms responsible for ovarian metastasis in gastric cancer, along with the complex and variable nature of the disease, single-treatment approaches often fail to yield significant results. To improve patient prognosis, the development of an individualised, comprehensive treatment plan tailored to the specific characteristics of each patient’s primary and metastatic lesions is essential. Furthermore, to improve the diagnosis and treatment of ovarian metastasis in patients with gastric cancer, future prospective, multicentre, large-sample clinical studies are needed.