Published online May 24, 2022. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v13.i5.376

Peer-review started: March 8, 2021

First decision: May 4, 2021

Revised: May 16, 2021

Accepted: April 20, 2022

Article in press: April 20, 2022

Published online: May 24, 2022

Following a total gastrectomy, patients suffer the most severe form of postgastrectomy syndrome. This is a significant clinical problem as it reduces quality of life (QOL). Roux-en-Y reconstruction, which is regarded as the gold standard for post-total gastrectomy reconstruction, can be performed using various techniques. Although the technique used could affect postoperative QOL, there are no previous reports regarding the same.

To investigate the effect of different techniques on postoperative QOL. The data was collected from the registry of the postgastrectomy syndrome assessment study (PGSAS).

In the present study, we analyzed 393 total gastrectomy patients from those enrolled in PGSAS. Patients were divided into groups depending on whether antecolic or retrocolic jejunal elevation was performed, whether the Roux limb was “40 cm”, “shorter” (≤ 39 cm), or “longer” (≥ 41 cm), and whether the device used for esophageal and jejunal anastomosis was a circular or linear stapler. Subsequently, we comparatively investigated postoperative QOL of the patients.

Reconstruction route: Esophageal reflux subscale (SS) occurred significantly less frequently in patients who underwent antecolic reconstruction. Roux limb length: “Shorter” Roux limb did not facilitate esophageal reflux SS and somewhat attenuated indigestion SS and abdominal pain SS. Anastomosis technique: In terms of esophagojejunostomy techniques, no differences were observed.

The techniques used for total gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction significantly affected postoperative symptoms. Our results suggest that elevating the Roux limb, which is not overly long, through an antecolic route may improve patients’ QOL.

Core Tip: Following a total gastrectomy using various techniques, patients suffer the severe form of postgastrectomy syndrome. We investigated the effect of different techniques in Roux-en-Y reconstruction on postoperative quality of life (QOL) using the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-45. We analyzed 393 total gastrectomy patients. Esophageal reflux subscale (SS) occurred significantly less frequently in patients who underwent antecolic reconstruction. Shorter Roux limb did not facilitate esophageal reflux SS and somewhat attenuated indigestion SS and abdominal pain SS. Our results suggest that elevating the Roux limb which is not overly long, through an antecolic route may improve patients’ QOL.

- Citation: Ikeda M, Yoshida M, Mitsumori N, Etoh T, Shibata C, Terashima M, Fujita J, Tanabe K, Takiguchi N, Oshio A, Nakada K. Assessing optimal Roux-en-Y reconstruction technique after total gastrectomy using the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-45. World J Clin Oncol 2022; 13(5): 376-387

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v13/i5/376.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v13.i5.376

Postgastrectomy syndrome is a serious clinical problem that decreases quality of life (QOL) of patients following gastrectomy[1-5]. As postgastrectomy syndrome is the severest form of the side effect following total gastrectomy[1,2,4,5], reducing the incidence of syndrome should be deliberated while choosing the surgical technique. Post-total gastrectomy Roux-en-Y reconstruction (TGRY) is a simple and robust form of reconstruction performed following a total gastrectomy, and it is widely performed and regarded as the gold standard. As laparoscopic surgery is more widely used in recent years, TGRY techniques have become more diverse now than when open surgery was used[6-12]. Although the differences in techniques appear to affect postoperative QOL, the reasons remain unclear due to lack of sufficient investigation. Therefore, we used Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-45 (PGSAS-45), which has developed for postgastrectomy evaluation, to investigate how TGRY surgical techniques affect postoperative QOL[13].

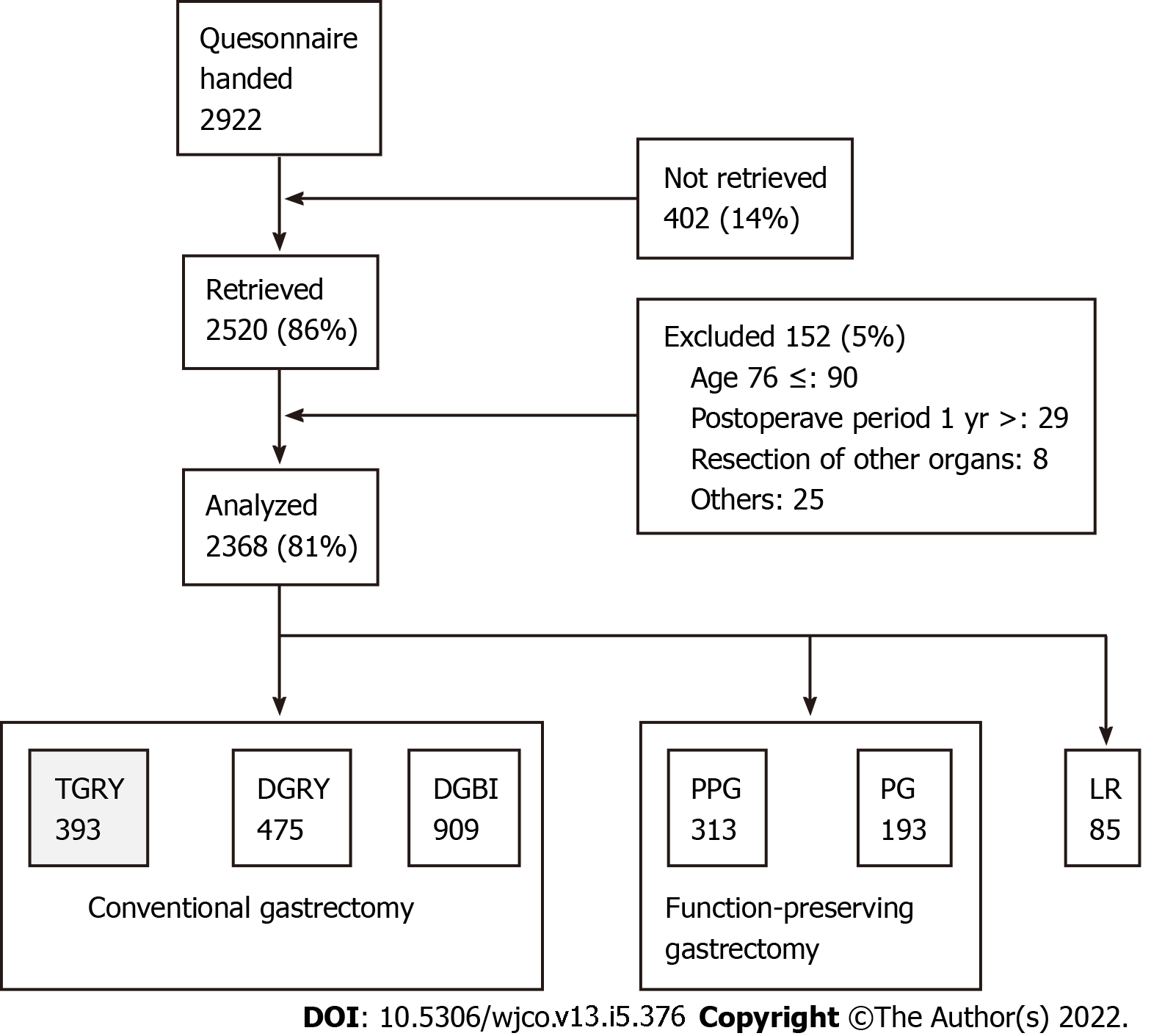

A total of 52 institutions participated in this study. A questionnaire was distributed to 2922 patients between July 2009 and December 2010 (Figure 1). Eligibility criteria for patients were as follows: (1) Diagnosis of pathologically-confirmed stage IA or IB gastric cancer[14]; (2) first-time gastrectomy; (3) aged 20-75 years; (4) no history of chemotherapy; (5) no recurrence or distant metastasis indicated; (6) gastrectomy conducted one or more years prior to the enrollment date; (7) performance status (PS) ≤ 1 on the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale[15-17]; (8) full capacity to understand and respond to the questionnaire; (9) no history of other diseases or surgeries which might influence responses to the questionnaire; (10) absence of organ failure or mental illness; and (11) written informed consent. Patients with dual malignancy or concomitant resection of other organs (with co-resection equivalent to cholecystectomy being the exception) were excluded. Of the distributed questionnaires, 2520 (86%) were retrieved; 152 questionnaires were excluded. A total of 2368 questionnaires were analyzed and it was observed that total gastrectomy was performed in 393 patients; all underwent reconstruction using Roux-en-Y method. Questionnaires of these 393 patients were selected for examination in this study.

PGSAS-45 consists of 45 items, including all eight items of the Short Form General Health Survey (SF-8)[18], all 15 items from the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale[19], and 22 newly-added items that cover various factors reflecting the postgastrectomy patient’s well-being (Table 1)[13].

| Domains | Subdomains | Items | Subscales |

| QOL | SF-8 (QOL) | 1 Physical functioning* | Physical component summary* (items 1-8) |

| 2 Role physical* | |||

| 3 Bodily pain* | Mental component summary* (items 1-8) | ||

| 4 General health* | |||

| 5 Vitality* | |||

| 6 Social functioning* | |||

| 7 Role emotional* | |||

| 8 Mental health* | |||

| Symptoms | GSRS (symptoms) | 9 Abdominal pains | Esophageal reflux subscale (items 10, 11, 13, 24) |

| 10 Heartburn | |||

| 11 Acid regurgitation | |||

| 12 Sucking sensations in the epigastrium | Abdominal pain subscale (items 9, 12, 28) | ||

| 13 Nausea and vomiting | |||

| 14 Borborygmus | Meal-related distress subscale (items 25-27) | ||

| 15 Abdominal distension | |||

| 16 Eructation | Indigestion subscale (items 14-17) | ||

| 17 Increased flatus | Diarrhea subscale (items 19, 20, 22) | ||

| 18 Decreased passage of stool | |||

| 19 Increased passage of stool | Constipation subscale (items 18, 21, 23) | ||

| 20 Loose stool | |||

| 21 Hard stool | Dumping subscale (items 30, 31, 33) | ||

| 22 Urgent need for defecation | |||

| 23 Feeling of incomplete evacuation | Total symptom score (above seven subscales) | ||

| Symptoms | 24 Bile regurgitation | ||

| 25 Sense of food sticking | |||

| 26 Postprandial fullness | |||

| 27 Early satiation | |||

| 28 Lower abdominal pain | |||

| 29 Number and type of early dumping symptoms | |||

| 30 Early dumping general symptoms | |||

| 31 Early dumping abdominal symptoms | |||

| 32 Number and type of late dumping symptoms | |||

| 33 Late dumping symptoms | |||

| Living status | Meals (amount) 1 | 34 Ingested amount of food per meal* | Quality of ingestion subscale* (items 38-40) |

| 35 Ingested amount of food per day* | |||

| 36 Frequency of main meals | |||

| 37 Frequency of additional meals | |||

| Meals (quality) | 38 Appetite* | ||

| 39 Hunger feeling* | |||

| 40 Satiety feeling* | |||

| Meals (amount) 2 | 41 Necessity for additional meals | ||

| Social activity | 42 Ability to work | ||

| QOL | Dissatisfaction (QOL) | 43 Dissatisfaction with symptoms | Dissatisfaction for daily life subscale (items 43-45) |

| 44 Dissatisfaction at the meals | |||

| 45 Dissatisfaction at working |

The following 18 outcome measures were evaluated, each consisting of a single item or an integration of related items from the PGSAS-45: esophageal reflux subscale (SS), abdominal pain SS, meal-related distress SS, indigestion SS, diarrhea SS, constipation SS, dumping SS, total symptom score, ingested amount of food per meal, necessity for additional meals, quality of ingestion SS, ability for working, dissatisfaction with symptoms, dissatisfaction at the meal, dissatisfaction at working and dissatisfaction for daily life SS, and the physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) of SF-8. Percentage changes in body weight (decrease in body weight/preoperative weight) were also determined as an outcome measure. These 19 main outcome measures were scored and classified into three domains: symptoms, living status, and QOL. Higher scores denote better outcomes for the items of PCS, MCS, ingested amount of food per meal, quality of ingestion SS, and changes in body weight, whereas lower scores denote better outcomes for the other 14 outcome measures.

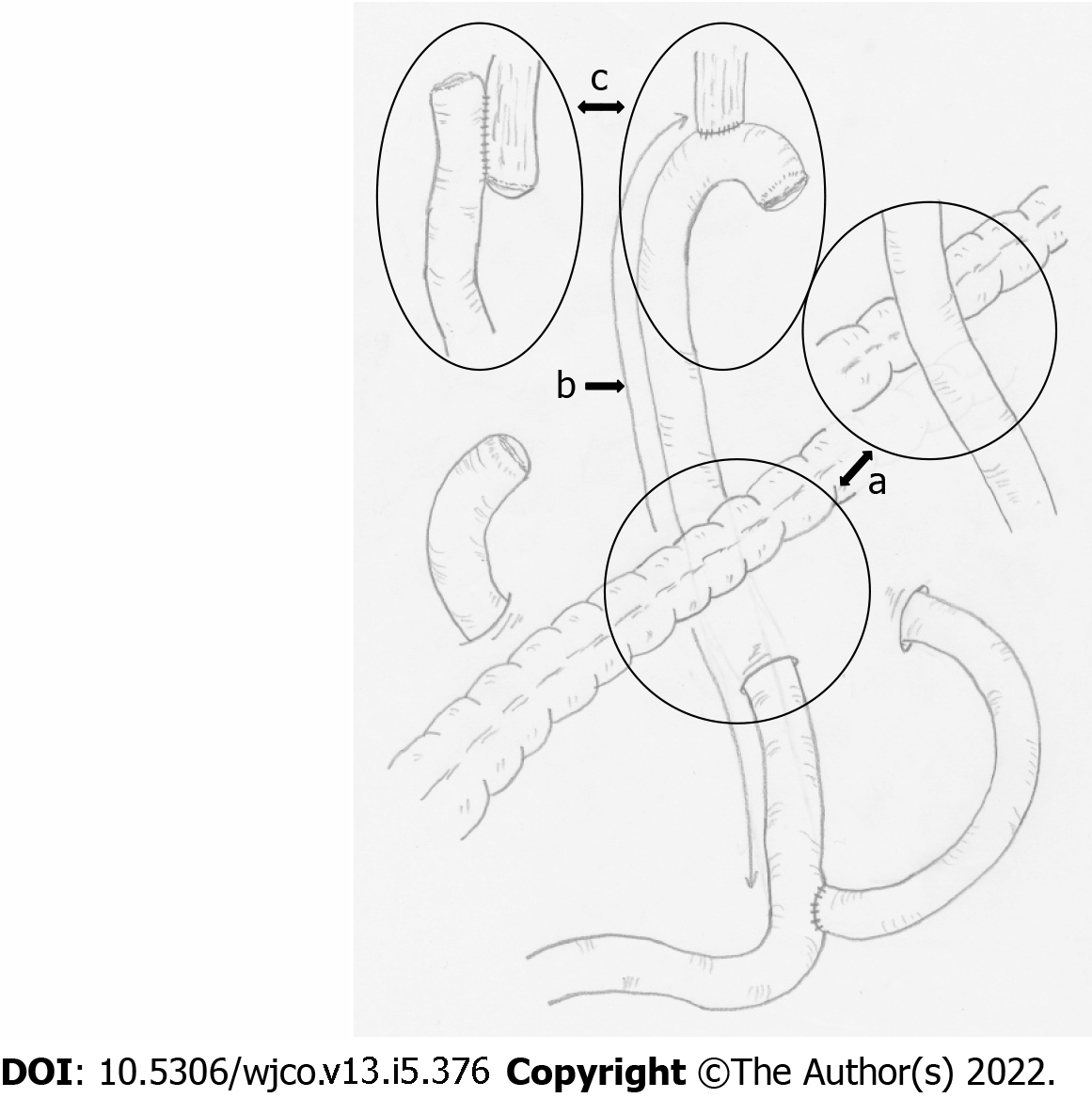

The gastrectomy patients were provided with a PGSAS-45 questionnaire by the surgeon during an outpatient visit. Each patient was asked to complete the questionnaire and mail it to the data center. The clinical data were reported to the data center by the responsible surgeons using case report form and matched to PGSAS-45 responses. All the data were analyzed at the data center. Postgastrectomy daily living was compared among: (1) Elevated route of Roux limb: antecolic vs retrocolic; (2) length of the Roux limb (defined as the distance from esophagojejunostomy to jejunojejunostomy): “shorter (≤ 39 cm)” vs “40 cm” vs “longer (≥ 41 cm)”; and (3) anastomotic procedure for esophagojejunostomy: circular stapler (CS) vs linear stapler (LS) (Figure 2). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of each participating institution and registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network’s Clinical Trials Registry (registration number, 000002116). All patients provided their written informed consent for the confidential use of their information in the data analysis, in compliance with institutional guidelines.

The values are shown as the mean ± SD. Two-group differences in the mean values were analyzed using an unpaired t-test and multiple-group differences were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Tukey multiple comparisons test was used when the ANOVA yielded a P value of < 0.1. Generally, a P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. When the P values were < 0.1 in the t-test or Tukey-test, the effect size (Cohen’s d) was calculated. The value of Cohen’s d reflects the impact of each causal variable: values between 0.2 and < 0.5 denote a small but clinically meaningful difference between the groups; values between 0.5 and < 0.8 denote a medium effect; and values ≥ 0.8 indicate a large effect. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP12.0.1 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States).

Characteristics of the 393 patients are listed in Table 2. The mean age was 63.4 years and the mean postoperative follow-up period was approximately 35 mo. It was observed that the number of male patients was more than the number of female patients and open surgery was more commonly used than laparoscopic surgery. The combined resection of another organ was performed for the gall bladder (83 patients) and spleen (52 patients). Dissection of the lymph node was over D1b in most of the patients. Conversely, celiac branch of the vagus nerve was not preserved in most patients.

| Characteristics | Values |

| Number of patients | 393 |

| Postoperative period (mo), mean ± SD | 35.0 ± 24.6 |

| Preoperative BMI, mean ± SD | 23.0 ± 3.3 |

| Postoperative BMI, mean ± SD | 19.8 ± 2.5 |

| Age, mean ± SD | 63.4 ± 9.2 |

| Gender (male/female) | 276/113 |

| Approach (laparoscopic/open) | 97/293 |

| Extent of lymph node dissection1 | |

| D2 | 164 |

| D1b | 192 |

| D1a | 28 |

| D1 | 4 |

| D1> | 0 |

| None | 0 |

| Celiac branch of the vagal nerve (preserved/divided) | 12/371 |

| Combined resection | |

| Gallbladder | 83 |

| Spleen | 52 |

| Miscellaneous | 2 |

| None | 246 |

The jejunum elevation route during Roux-en-Y reconstruction was described for 385 (98.0%) patients (Table 3). Retrocolic elevation (206 patients) was performed more commonly than antecolic elevation (179 patients). Among the 19 main outcome measures, scores for the esophageal reflux SS were significantly superior in antecolic elevation group compared to retrocolic elevation group with small but clinically meaningful effect (P = 0.028, Cohen’s = 0.23).

| Reconstruction route of Roux limb | Retro-colica (n = 206) | Ante-colica (n = 179) | P value | Cohens d | ||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | |||

| Esophageal reflux SS | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.028 | 0.229 |

| Abdominal pain SS | 1.8 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 0.8 | NS | |

| Meal-related distress SS | 2.7 | 1.1 | 2.6 | 1.1 | NS | |

| Indigestion SS | 2.3 | 0.98 | 2.3 | 0.9 | NS | |

| Diarrhea SS | 2.4 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 1.1 | NS | |

| Constipation SS | 2.1 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 0.8 | NS | |

| Dumping SS | 2.4 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 1.1 | NS | |

| Total symptom score | 2.2 | 0.8 | 2.1 | 0.7 | NS | |

| Change in Body weight | -13.6% | 7.8% | -14.0% | 8.1% | NS | |

| Ingested amount of food per meal | 6.5 | 1.9 | 6.4 | 1.8 | NS | |

| Necessity for additional meals | 2.3 | 0.8 | 2.4 | 0.7 | NS | |

| Quality of ingestion SS | 3.7 | 1.0 | 3.8 | 0.9 | NS | |

| Ability to work | 2.1 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 0.8 | NS | |

| Dissatisfaction with symptoms | 2.1 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | NS | |

| Dissatisfaction at the meal | 2.8 | 1.1 | 2.8 | 1.1 | NS | |

| Dissatisfaction at working | 2.1 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.0 | NS | |

| Dissatisfaction for daily life SS | 2.4 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 0.9 | NS | |

| Physical component summary | 49.2 | 5.8 | 50.1 | 5.4 | NS | |

| Mental component summary | 49.1 | 6.1 | 49.2 | 5.9 | NS | |

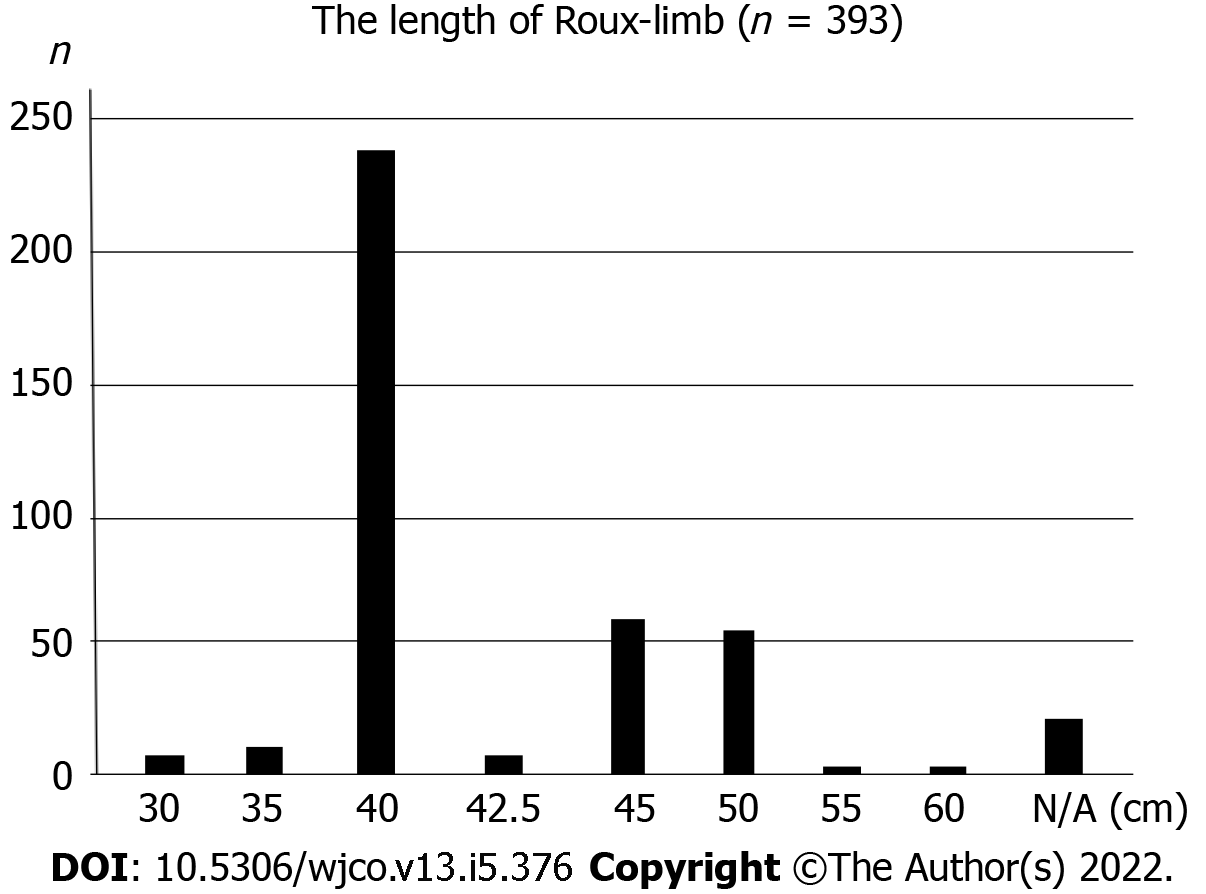

Of the 393 patients, the length of the Roux limb was described in 373 (94.9%) patients (Table 4). The most common Roux limb length was “40 cm” (238 patients), followed by “longer (≥ 41 cm)” (119 patients) and “shorter (≤ 39 cm)” (16 patients) Roux limb length (Figure 3). “Shorter” Roux limb length had not worsen the esophageal reflux SS, and rather reduced the indigestion SS compared to both the “40 cm” and “longer” Roux limb groups with medium effect size in terms of Cohen’s d values (shorter vs 40 cm: P = 0.020, Cohen’s d = 0.69; “shorter” vs “longer”: P = 0.030, Cohen’s d = 0.68, respectively). In addition, “shorter” Roux limb attenuated abdominal pain SS with marginal significance (P = 0.081).

| Length of Roux limb | Shorter (n = 16) | 40 cm (n = 238) | Longer (n = 119) | ANOVA | Multiple comparisons | P value | Cohens d | |||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | mean | SD | P value | ||||

| Esophageal reflux SS | 1.8 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.0 | NS | |||

| Abdominal pain SS | 1.4 | 0.4 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0.081 | Shorter vs 40 cm | 0.053 | 0.52 |

| Meal-related distress SS | 2.2 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 2.7 | 1.0 | NS | |||

| Indigestion SS | 1.7 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 0.026 | Shorter vs 40 cm | 0.020 | 0.69 |

| Shorter vs longer | 0.030 | 0.68 | ||||||||

| Diarrhea SS | 2.0 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 1.2 | NS | |||

| Constipation SS | 2.3 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 0.9 | NS | |||

| Dumping SS | 1.8 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 1.1 | 2.3 | 1.1 | NS | |||

| Total symptom score | 1.9 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 0.7 | NS | |||

| Change in Body weight | -14.1% | 8.6% | -13.8% | 8.2% | -13.5% | 7.5% | NS | |||

| Ingested amount of food per meal | 5.5 | 2.6 | 6.4 | 1.9 | 6.5 | 1.7 | NS | |||

| Necessity for additional meals | 2.4 | 0.8 | 2.4 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 0.7 | NS | |||

| Quality of ingestion SS | 3.3 | 1.2 | 3.8 | 0.9 | 3.8 | 1.0 | NS | |||

| Ability to work | 2.4 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 0.9 | NS | |||

| Dissatisfaction with symptoms | 1.8 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.0 | NS | |||

| Dissatisfaction at the meal | 3.3 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 1.2 | 2.8 | 1.0 | NS | |||

| Dissatisfaction at working | 2.5 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 1.0 | NS | |||

| Dissatisfaction for daily life SS | 2.5 | 1.0 | 2.3 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 0.8 | NS | |||

| Physical component summary | 49.2 | 6.7 | 49.4 | 5.7 | 50.1 | 5.5 | NS | |||

| Mental component summary | 48.1 | 5.9 | 48.7 | 6.3 | 49.9 | 5.5 | NS | |||

Of the 393 patients, the device used for anastomosis between the esophagus and jejunum was described in 388 (98.7%) patients (Table 5). The CS was used in 348 patients, while the LS was used in 40 patients. Among the 19 main outcome measures of PGSAS-45, there was no difference between the two procedures.

| Anastomotic method | Circular stapler(n = 348) | Liner stapler (n = 40) | P value | ||

| mean | SD | mean | SD | ||

| Esophageal reflux SS | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 0.8 | NS |

| Abdominal pain SS | 1.8 | 0.8 | 1.7 | 0.8 | NS |

| Meal-related distress SS | 2.6 | 1.1 | 2.8 | 1.2 | NS |

| Indigestion SS | 2.3 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 0.8 | NS |

| Diarrhea SS | 2.3 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 1.3 | NS |

| Constipation SS | 2.1 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 1.0 | NS |

| Dumping SS | 2.3 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 1.1 | NS |

| Total symptom score | 2.2 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 0.7 | NS |

| Change in Body weight | -13.9% | 7.9% | -12.8% | 7.9% | NS |

| Ingested amount of food per meal | 6.5 | 1.9 | 6.2 | 1.8 | NS |

| Necessity for additional meals | 2.3 | 0.8 | 2.4 | 0.8 | NS |

| Quality of ingestion SS | 3.8 | 1.0 | 3.8 | 0.9 | NS |

| Ability to work | 2.0 | 0.9 | 2.1 | 0.9 | NS |

| Dissatisfaction with symptoms | 2.1 | 1.0 | 2.1 | 0.9 | NS |

| Dissatisfaction at the meal | 2.8 | 1.1 | 3.0 | 1.0 | NS |

| Dissatisfaction at working | 2.1 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.0 | NS |

| Dissatisfaction for daily life SS | 2.3 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 0.8 | NS |

| Physical component summary | 49.6 | 5.7 | 50.2 | 4.9 | NS |

| Mental component summary | 49.2 | 6.0 | 49.2 | 5.9 | NS |

Postgastrectomy syndrome is the severest following total gastrectomy and persists in the long-term; thereby, lowering patients’ QOL[1,2,4,5]. Therefore improvement of surgical techniques to reduce the onset of this syndrome is important. TGRY is a simple and robust technique that is performed widely and regarded as the gold standard for post-total gastrectomy reconstruction. While the increased use of laparoscopic surgery and anastomotic devices has resulted in the diversification of TGRY surgical techniques[6-12], the effects of different TGRY techniques on patients’ QOL remains unknown. Our results indicate that elevation of the Roux limb via antecolic route resulted in fewer esophageal reflux SS, and the relatively “shorter” Roux limb length accompanied by fewer indigestion SS without increasing esophageal reflux SS. In terms of device selection for esophagojejunostomy, no difference was observed between the CS and LS procedures. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to demonstrate that differences in surgical techniques in TGRY affect postoperative QOL.

The Roux limb reconstruction in TGRY has often been performed via retrocolic route in open surgeries, as it applies slight tension to the anastomosis due to the short distance to the esophageal stump. With the increased use of laparoscopic surgery, surgeons began elevating the Roux limb via antecolic route due to its technical simplicity[7]. And then, the antecolic elevation became more common even for open total gastrectomy. Our investigation into the effects of different Roux limb reconstruction routes in TGRY on postoperative QOL indicate that esophageal reflux SS was significantly attenuated in the antecolic route group than the retrocolic route group. One of the possible explanation is that in the antecolic reconstruction, duodenal fluid hardly flow back into the esophagus unless it passes over the height of the transverse colon when the patient took the lying-down position. As a result, this physical barrier of gravity could attenuate the esophageal reflux SS in addition to the preventive effect of the peristalsis of the Roux limb. Based on these, the antecolic route may be a suitable surgical procedure when performing TGRY. Although the caution is needed for the occurrence of the internal hernia through Petersen’s defect especially when the gastrectomy underwent laparoscopically, and the implementing preventive methods such as the closure of these defects with sutures[20,21] should be performed.

Many surgeons concern that the insufficient length of Roux limb likely to increase the esophageal regurgitation. However, in the present study, the esophageal reflux SS did not worsened in the “shorter” Roux limb length group compared to the other groups, therefore, even relatively short Roux limbs of 30-35 cm may have produced the sufficient intestinal peristalsis to prevent esophageal regurgitation. Interestingly, significantly more indigestion SS was observed in the “40 cm” and “longer” Roux limb length groups compared to the “shorter” group. This may be, in part, explained by the previous report[22] showing that relatively long Roux limbs could be a cause of Roux-en-Y syndrome. The Roux limb length should be adjusted as an appropriate length, and not too long[22].

Although esophagojejunostomy in TGRY had mainly performed using the CS, the increase in laparoscopic surgery has resulted in the diversification of anastomotic techniques and the esophagojejunostomy using the LS is increasing[9-11]. Comparison of the CS and LS procedures in terms of the effect of the esophagojejunostomy technique on postoperative QOL revealed no differences in any of the main outcome measures of PGSAS-45, therefore, either of the CS or LS procedures can be selected depending on the clinical situation to achieve a safe and simple anastomosis procedure.

Many surgeons had chosen the retrocolic route as that of the Roux limb from the problems concerned with the distance of Roux limb and occurrence of internal hernia, and enough length of the Roux limb preventing the regurgitation to esophagus. The result of this PGSAS study may provide a hint for the optimal surgical procedures after total gastrectomy. A limitation of the present study is its retrospective nature and the unbalanced number of patients in each group. A well-designed prospective study should be conducted in the future.

Our results revealed that the specific surgical technique used for TGRY affects postoperative QOL to some extent. Since postgastrectomy syndrome is the severest following total gastrectomy, a technique that could maintain a favorable postoperative QOL should be selected. The findings of this study suggest that some of the postgastrectomy symptoms following TGRY could be attenuated by elevating Roux limb through antecolic route with not too long Roux limb length.

Following a total gastrectomy using various techniques, some patients suffer the severe form of postgastrectomy syndrome.

Although the differences in techniques of Roux-en-Y reconstruction appear to affect postoperative quality of life (QOL), the reasons remain unclear due to lack of sufficient investigation.

We investigated the effect of different techniques on postoperative QOL.

Using the Postgastrectomy Syndrome Assessment Scale-45, we investigated the effect of different techniques in Roux-en-Y reconstruction on postoperative QOL. We analyzed 393 total gastrectomy patients.

Esophageal reflux subscale (SS) occurred significantly less frequently in patients who underwent antecolic reconstruction. Shorter Roux limb did not facilitate esophageal reflux SS and somewhat attenuated indigestion SS and abdominal pain SS.

Our results suggest that elevating the Roux limb which is not overly long, through an antecolic route may attenuate some of the postgastrectomy symptoms.

Patients’ QOL after total gastrectomy may be improved by this study.

The authors thank all the physicians who participated in this study and the patients whose cooperation made this study possible. This study was completed by 52 institutions in Japan. The contributor of each institution is listed below. Masanori Terashima (Shizuoka Cancer Center), Junya Fujita (Sakai City Medical Center), Kazuaki Tanabe (Hiroshima University), Nobuhiro Takiguchi (Chiba Cancer Center), Masazumi Takahashi (Yokohama Municipal Citizen’s Hospital), Kazunari Misawa (Aichi Cancer Center Hospital), Koji Nakada (The Jikei University School of Medicine), Norio Mitsumori (The Jikei University School of Medicine), Hiroshi Kawahira (Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University), Tsutomu Namikawa (Kochi Medical School), Takao Inada (Tochigi Cancer Center), Hiroshi Okabe (Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine), Takashi Urushihara (Hiroshima Prefectural Hospital), Yoshiyuki Kawashima (Saitama Cancer Center), Norimasa Fukushima (Yamagata Prefectural Central Hospital), Yasuhiro Kodera (Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine), Takeyoshi Yumiba (Osaka Kosei-Nenkin Hospital), Hideo Matsumoto (Kawasaki Medical School), Akinori Takagane (Hakodate Goryoukaku Hospital), Chikara Kunisaki (Yokohama City University Medical Center), Ryoji Fukushima (Teikyo University School of Medicine), Hiroshi Yabusaki (Niigata Cancer Center Hospital), Akiyoshi Seshimo (Tokyo Women’s Medical University), Naoki Hiki (Cancer Institute Hospital), Keisuke Koeda (Iwate Medical University), Mikihiro Kano (JA Hiroshima General Hospital), Yoichi Nakamura (Toho University Ohashi Medical Center), Makoto Yamada (Gifu Municipal Hospital), SangWoong Lee (Osaka Medical College), Shinnosuke Tanaka (Fukuoka University School of Medicine), Akira Miki (Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital), Masami Ikeda (Yokosuka General Hospital Uwamachi), Satoshi Inagawa (University of Tsukuba), Shugo Ueda (Kitano Hospital), Takayuki Nobuoka (Sapporo Medical University School of Medicine), Manabu Ohta (Hamamatsu University school of Medicine), Yoshiaki Iwasaki (Tokyo Metropolitan Cancer and Infectious diseases Center Komagome Hospital), Nobuyuki Uchida (Haramachi Redcross Hospital), Eishi Nagai (Graduate School of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University), Yoshikazu Uenosono (Kagoshima University Graduate School of Medicine), Shinichi Kinami (Kanazawa Medical University), Yasuhiro Nagata (National Hospital Organization Nagasaki Medical Center), Masashi Yoshida (International University of Health and Welfare, Mita Hospital), Keishiro Aoyagi (School of Medicine Kurume University), Shuichi Ota (Osaka Saiseikai Noe hospital), Hiroaki Hata (National Hospital Organization, Kyoto Medical Center), Hiroshi Noro (Otemae Hospital), Kentaro Yamaguchi (Tokyo Women’s Medical University Medical Center East), Hiroshi Yajima (The Jikei University Kashiwa Hospital), Toshikatsu Nitta (Shiroyama Hospital), Tsuyoshi Etoh (Oita University), Chikashi Shibata (Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine), Atsushi Oshio (Waseda University).

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Japan Surgical Society, No. 0229736; The Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Surgery, No. G0085947; Japanese Gastric Cancer Association, No. 5787; The Japanese Society for Gastro-surgical Pathophysiology; and Japanese Society of Clinical Surgeons, No. 1184.

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tharavej C S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Gong ZM

| 1. | Karanicolas PJ, Graham D, Gönen M, Strong VE, Brennan MF, Coit DG. Quality of life after gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma: a prospective cohort study. Ann Surg. 2013;257:1039-1046. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 107] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lee JH, Lee HJ, Choi YS, Kim TH, Huh YJ, Suh YS, Kong SH, Yang HK. Postoperative Quality of Life after Total Gastrectomy Compared with Partial Gastrectomy: Longitudinal Evaluation by European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer-OG25 and STO22. J Gastric Cancer. 2016;16:230-239. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rausei S, Mangano A, Galli F, Rovera F, Boni L, Dionigi G, Dionigi R. Quality of life after gastrectomy for cancer evaluated via the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-STO22 questionnaires: surgical considerations from the analysis of 103 patients. Int J Surg. 2013;11 Suppl 1:S104-S109. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Takiguchi N, Takahashi M, Ikeda M, Inagawa S, Ueda S, Nobuoka T, Ota M, Iwasaki Y, Uchida N, Kodera Y, Nakada K. Long-term quality-of-life comparison of total gastrectomy and proximal gastrectomy by postgastrectomy syndrome assessment scale (PGSAS-45): a nationwide multi-institutional study. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:407-416. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 135] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tanizawa Y, Tanabe K, Kawahira H, Fujita J, Takiguchi N, Takahashi M, Ito Y, Mitsumori N, Namikawa T, Oshio A, Nakada K; Japan Postgastrectomy Syndrome Working Party. Specific Features of Dumping Syndrome after Various Types of Gastrectomy as Assessed by a Newly Developed Integrated Questionnaire, the PGSAS-45. Dig Surg. 2016;33:94-103. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hirahara N, Monma H, Shimojo Y, Matsubara T, Hyakudomi R, Yano S, Tanaka T. Reconstruction of the esophagojejunostomy by double stapling method using EEA™ OrVil™ in laparoscopic total gastrectomy and proximal gastrectomy. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:55. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hosoya Y, Lefor A, Ui T, Haruta H, Kurashina K, Saito S, Zuiki T, Sata N, Yasuda Y. Internal hernia after laparoscopic gastric resection with antecolic Roux-en-Y reconstruction for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3400-3404. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhao YL, Su CY, Li TF, Qian F, Luo HX, Yu PW. Novel method for esophagojejunal anastomosis after laparoscopic total gastrectomy: semi-end-to-end anastomosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13556-13562. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kitagami H, Morimoto M, Nakamura K, Watanabe T, Kurashima Y, Nonoyama K, Watanabe K, Fujihata S, Yasuda A, Yamamoto M, Shimizu Y, Tanaka M. Technique of Roux-en-Y reconstruction using overlap method after laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: 100 consecutively successful cases. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4086-4091. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Huang ZN, Huang CM, Zheng CH, Li P, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lin JX, Lu J, Chen QY, Cao LL, Lin M, Tu RH, Lin JL. Digestive tract reconstruction using isoperistaltic jejunum-later-cut overlap method after totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy for gastric cancer: Short-term outcomes and impact on quality of life. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:7129-7138. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gong CS, Kim BS, Kim HS. Comparison of totally laparoscopic total gastrectomy using an endoscopic linear stapler with laparoscopic-assisted total gastrectomy using a circular stapler in patients with gastric cancer: A single-center experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:8553-8561. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Norero E, Muñoz R, Ceroni M, Manzor M, Crovari F, Gabrielli M. Two-Layer Hand-Sewn Esophagojejunostomy in Totally Laparoscopic Total Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer. J Gastric Cancer. 2017;17:267-276. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nakada K, Ikeda M, Takahashi M, Kinami S, Yoshida M, Uenosono Y, Kawashima Y, Oshio A, Suzukamo Y, Terashima M, Kodera Y. Characteristics and clinical relevance of postgastrectomy syndrome assessment scale (PGSAS)-45: newly developed integrated questionnaires for assessment of living status and quality of life in postgastrectomy patients. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:147-158. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 86] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113-123. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1723] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1844] [Article Influence: 141.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, Bullinger M, Cull A, Duez NJ, Filiberti A, Flechtner H, Fleishman SB, de Haes JC, Kaasa S, Klee M, Osoba D, Razavi D, Rofe PB, Schraub S, Sneeuw K, Sullivan M, Takeda F. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:365-376. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9802] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10495] [Article Influence: 338.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sprangers MA, Cull A, Groenvold M, Bjordal K, Blazeby J, Aaronson NK. The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer approach to developing questionnaire modules: an update and overview. EORTC Quality of Life Study Group. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:291-300. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 67] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kaasa S, Bjordal K, Aaronson NK, Moum T, Wist E, Hagen S, Kvikstad A. The EORTC core quality of life questionnaire (QLQ-C30): validity and reliability when analysed with patients treated with palliative radiotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:2260-2263. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 258] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Turner-Bowker DM, Bayliss MS, Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M. Usefulness of the SF-8 Health Survey for comparing the impact of migraine and other conditions. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:1003-1012. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 245] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Svedlund J, Sjödin I, Dotevall G. GSRS--a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:129-134. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 884] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 925] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kimura H, Ishikawa M, Nabae T, Matsunaga T, Murakami S, Kawamoto M, Kamimura T, Uchiyama A. Internal hernia after laparoscopic gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction for gastric cancer. Asian J Surg. 2017;40:203-209. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ojima T, Nakamori M, Nakamura M, Katsuda M, Hayata K, Kato T, Tsuji T, Yamaue H. Internal Hernia After Laparoscopic Total Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2017;27:470-473. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gustavsson S, Ilstrup DM, Morrison P, Kelly KA. Roux-Y stasis syndrome after gastrectomy. Am J Surg. 1988;155:490-494. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 137] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |