Published online Feb 24, 2022. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v13.i2.71

Peer-review started: March 1, 2021

First decision: September 2, 2021

Revised: September 19, 2021

Accepted: January 17, 2022

Article in press: January 17, 2022

Published online: February 24, 2022

Processing time: 358 Days and 12.4 Hours

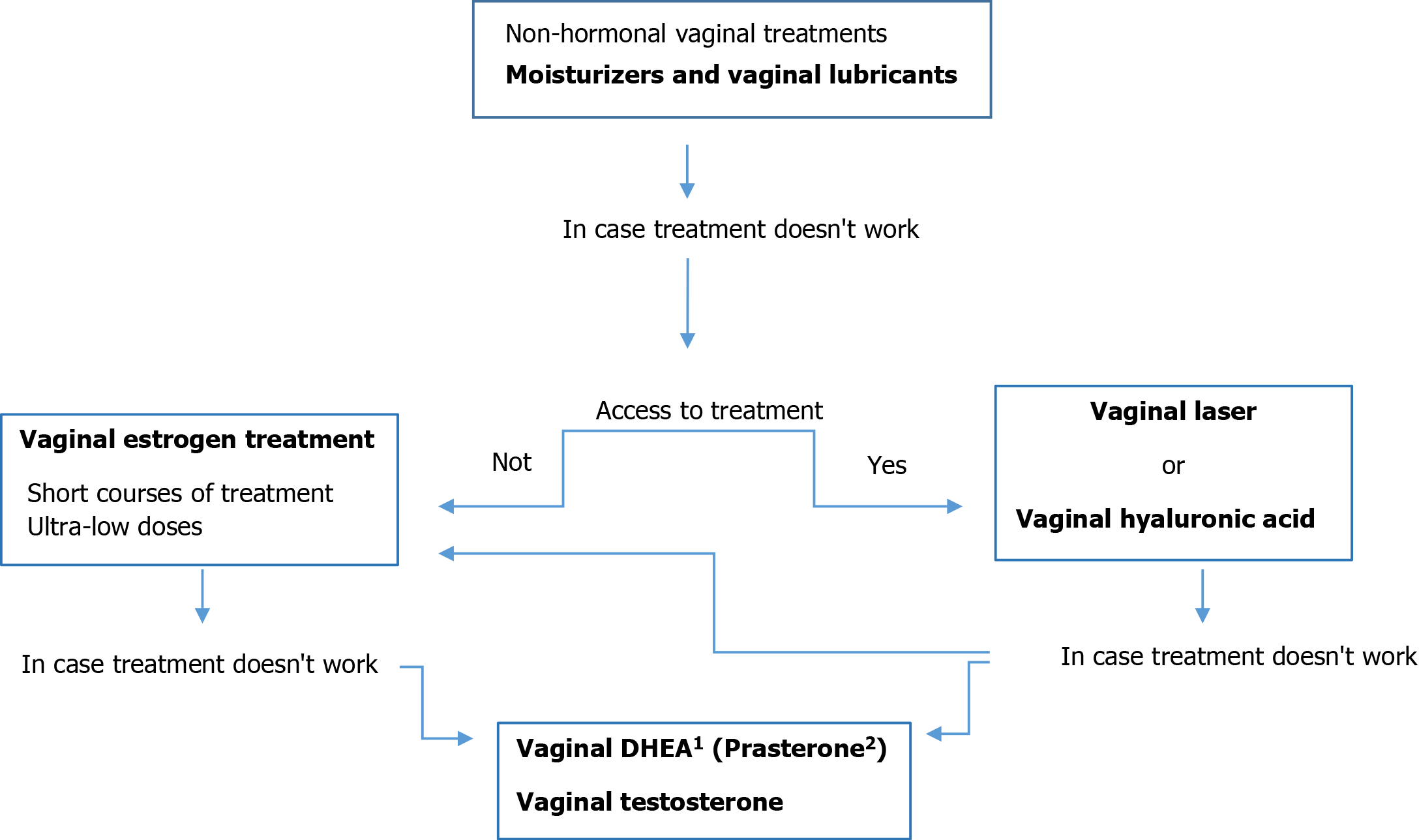

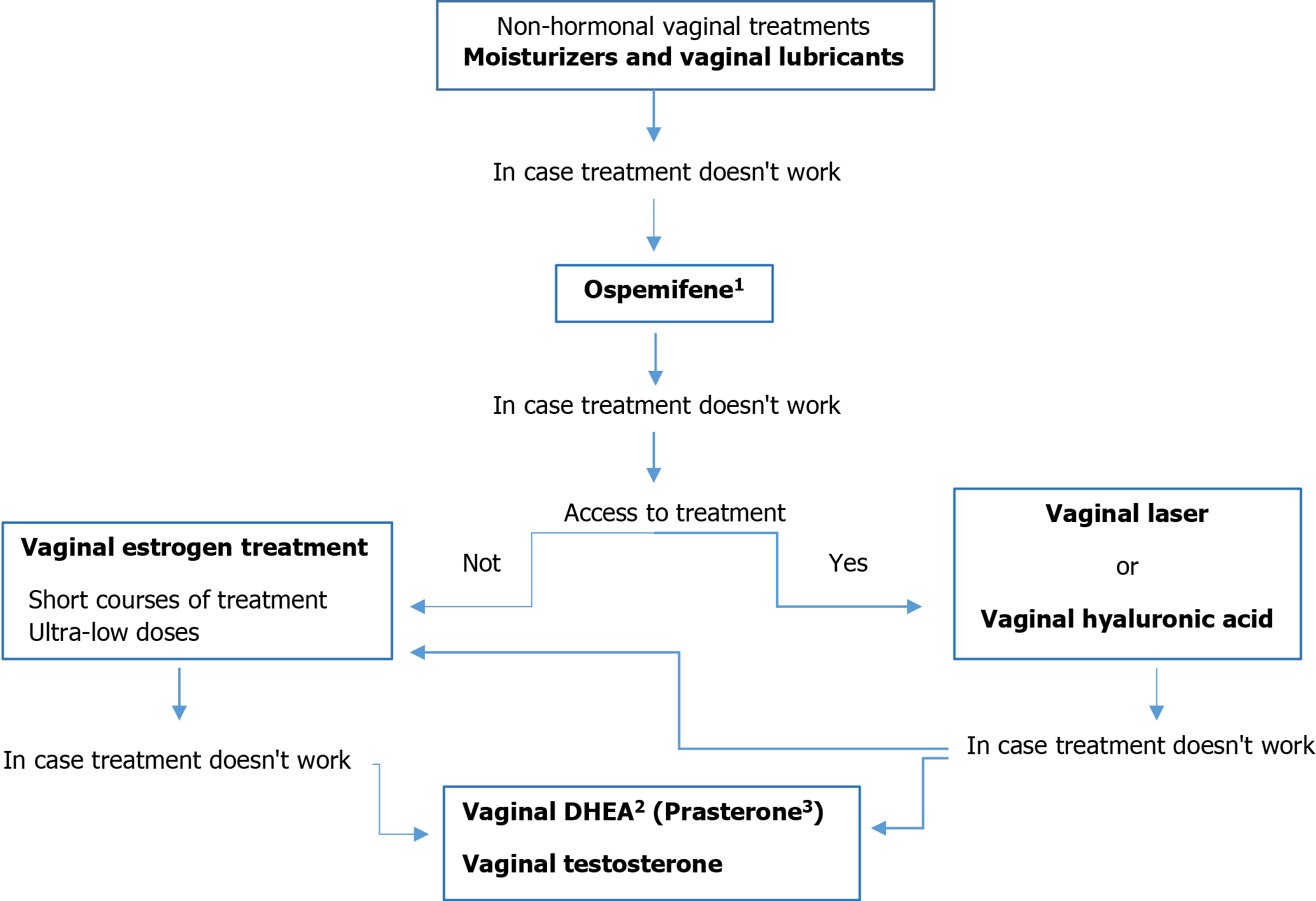

There is increasing attention about managing the adverse effects of adjuvant therapy (Chemotherapy and anti-estrogen treatment) for breast cancer survivors (BCSs). Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA), caused by decreased levels of circulating estrogen to urogenital receptors, is commonly experienced by this patients. Women receiving antiestrogen therapy, specifically aromatase inhibitors, often suffer from vaginal dryness, itching, irritation, dyspareunia, and dysuria, collectively known as genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), that it can in turn lead to pain, discomfort, impairment of sexual function and negatively impact on multiple domains of quality of life (QoL). The worsening of QoL in these patients due to GSM symptoms can lead to discontinuation of hormone adjuvant therapies and therefore must be addressed properly. The diagnosis of VVA is confirmed through patient-reported symptoms and gynecological examination of external structures, introitus, and vaginal mucosa. Systemic estrogen treatment is contraindicated in BCSs. In these patients, GSM may be prevented, reduced and managed in most cases but this requires early recognition and appropriate treatment, but it is normally undertreated by oncologists because of fear of cancer recurrence, specifically when considering treatment with vaginal estrogen therapy (VET) because of unknown levels of systemic absorption of estradiol. Lifestyle modifications and nonhormonal treatments (vaginal moisturizers, lubricants, and gels) are the first-line treatment for GSM both in healthy women as BCSs, but when these are not effective for symptom relief, other options can be considered, such as VET, ospemifene, local androgens, intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (prasterone), or laser therapy (erbium or CO2 Laser). The present data suggest that these therapies are effective for VVA in BCSs; however, safety remains controversial and a there is a major concern with all of these treatments. We review current evidence for various nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic modalities for GSM in BCSs and highlight the substantial gaps in the evidence for safe and effective therapies and the need for future research. We include recommendations for an approach to the management of GSM in women at high risk for breast cancer, women with estrogen-receptor positive breast cancers, women with triple-negative breast cancers, and women with metastatic disease.

Core Tip: Genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) is commonly experienced by breast cancer survivors (BCSs) receiving antiestrogen therapy, specifically aromatase inhibitors. Vaginal dryness, itching, irritation and dyspareunia produce impairment of sexual function and negatively impact on the quality of life. Healthy women, and even more so BCSs, are reluctant to discuss this problem with their general practitioner or oncologist. Safety of vaginal estrogen therapy for management of GSM refractory to other nonhormonal treatment in BCSs has not been definitively established, and recommendations for use remain controversial. This review aims to summarize the clinical approach and emerging therapeutic alternatives, considering the efficacy and potencial adverse effects in this population.

- Citation: Lubián López DM. Management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in breast cancer survivors: An update. World J Clin Oncol 2022; 13(2): 71-100

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v13/i2/71.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v13.i2.71

Vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) (also referred to as vaginal atrophy, urogenital atrophy, or atrophic vaginitis) results from estrogen loss and is often associated with vulvovaginal complaints (e.g., dryness, burning, dyspareunia) and less often with urinary frequency and recurrent bladder infections in menopausal patients[1].

In 2014, the new term Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause (GSM) was introduced by the International Society for the Study of Women´s Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society[2]. This term encompasses all of the atrophic symptoms patients may have in the vulvovaginal and bladder-urethral areas from loss of estrogen that occurs with menopause. The spectrum of adverse consequences makes long-term treatment essential in many patients, not only for relief of symptoms, but also for the more troublesome problems that may occur, such as, postcoital bleeding and recurrent urinary tract infections. This in turn can complicate the process of sexual arousal and achievement of orgasm, thus, leading to sexual dysfunction[3].

The prevalence of VVA, as confirmed by physical examination or pH measurement, has been described as between 69% and 98% in postmenopausal women[4,5], but it is even more frequent in young patients receiving anti-estrogenic or antineoplastic drugs for breast cancer[6]. These symptoms are often underdiagnosed and undertreated due to underreporting by the patients and limited awareness by professionals[7].

Improved treatment and screening for female breast cancer in developed countries has resulted in higher survival rates over the past two decades, with five-year survival rates currently as high as 90% (99% for women free of lymph node metastases in comparison to 84% if lymph nodes are positive)[8]. As a result, there are many millions of BCSs living in Western countries. In these countries, approximately 43% are ≥ 65 years old and 25% are ≤ 50 at diagnosis[9].

There are many definitions and phases of cancer survivorship. A cancer survivor is defined as any person with cancer, starting from the moment of diagnosis[10]. This is consistent with definitions from the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship[11] and the National Cancer Institute[12]. The majority of women with hormone receptor-positive early breast cancer are offered adjuvant endocrine therapy, including tamoxifen (TAM) or aromatase inhibitors (AIs), for at least 5 years to reduce the risk of recurrence and death. Practice guidelines now recommend up to 10 years of endocrine therapy and this has significant implications for compliance with treatment and ensuring that the adverse effects of treatment are adequately managed[13]. Many BCSs are still of premenopausal age and have the potential risk of receiving antineoplastic treatments that may affect ovarian function or anti-estrogenic treatments that mimic a postmenopausal state[14]. This hypoestrogenic state can lead to climacteric symptoms inducing significant alterations in their quality of life[15]. Many BCSs are already in a postmenopausal state at diagnosis, and the treatments used to treat BC worsens their basal hypoestrogenic state, which enhances associated problems. Due to dependence on estrogen, the vaginal epithelium can progress to VVA because of antiestrogenic treatments or natural menopause. Data suggest that long-term BCSs often report normalization of physical and emotional functioning but experience continued difficulty with sexual functioning and satisfaction for 5 or more years after treatment[16]. Women may be reluctant to bring up the topic of vaginal and sexual health and are often relieved when their clinicians begin a conversation. Many clinicians are uncertain about how to treat these symptoms in BCSs[17,18], and lack of treatment usually leads to a worsening of VVA over time[19].

Therefore, the management of breast cancer, the most common cancer in women, can lead to a variety of symptoms that can impair the quality of life (QoL) of many survivors. Although GSM affects more than 50% of the general population of postmenopausal women, it is even more prevalent in survivors of breast cancer (over 70%)[20-27], most of whom are undiagnosed and untreated[28-32]. This wide range of symptoms is a consequence of the decreased levels of circulating estrogen caused by ovarian failure induced by chemotherapy, bilateral oophorectomy performed in some patients, or by the use of endocrine therapies with AIs and selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs), such as TAM, in estrogen-receptor-positive BCs (ER+BCs), resulting in a faster transition to menopause[14,15].

Postmenopausal women treated with AIs may experience a severe form of vulvovaginal atrophy (VVA) with significantly higher rates of vaginal dryness (16.3%) and dyspareunia (17.8%) than women taking TAM (8.4% and 7.5%, respectively), as reported by The Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) Adjuvant Breast Cancer Trial[33]. Data originating from a follow-up study of women with breast cancer no longer on therapy and 6 years on average after diagnosis showed that in the group of women aged 50 to 59, 72.8% reported vasomotor symptoms (VMS), and 80.8% reported sexual symptoms[20]. Another study with 97 BCSs reported moderate or severe symptoms of vaginal atrophy in 58% of patients on AIs and in 32% of those on TAM[34].

Several studies have suggested a deterioration of quality-of-life scores due to GSM in BCSs[35,36].

In a recent study, Lubián et al(2020)[37], observed a high prevalence of sexual inactivity among BCSs (47.6%) regardless of AI use. Patients with AI use presented a significantly higher prevalence of female sexual dysfunction (FSD), worse QoL, and greater anxiety.

We can conclude that AI users usually report more negative effects on sexual life than TAM users. These differences could be explained by some estrogenic effect of TAM over vaginal tissues in postmenopausal women, whereas AI can dramatically reduce plasma estradiol levels to less than 3 pmol/L[38].

Therefore, the aim of this review was to provide an update and overview of the most relevant and recent literature on therapeutic interventions with demonstrated efficacy in BCSs presenting GSM and the current evidence of their safety profiles. In addition, we provide recommendations for an approach to the management of GSM in women at high risk of breast cancer, women with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancers (ER+BCs), women with triple-negative breast cancers (TN BCs), and women with metastatic disease.

Systemic loss of estrogen results in physiological and structural modifications within the genital structures and vaginal mucosa. Postmenopausal estrogen depletion induces changes that include a reduction in cervical gland secretions, deterioration of tissue, decrease in blood flow, loss of elasticity, thinning of tissue and epithelium, and an increase in pH[39-41]. The vaginal mucosa has reduced glycogen content and lack lactobacilli which convert glycogen into lactic acid to maintain a healthy vaginal pH in the range of 3.5-4.5. A reduction in lactic acid increases vaginal pH to the range of 5.0-7.5[39,42]. Such atrophic changes predispose women to symptoms and vaginal infections, as the more basic pH environment is conducive for infection from pathogenic bacteria such as staphylococci and Group B streptococci[39]. In summary, atrophic vaginitis is a result of multiple changes in the external genitalia and internal mucosa with inflammation, overgrowth of pathogens, and a resultant acidic environment[41].

The majority of women with BC receive systemic treatment (chemo-, hormonal- or biologic therapies) to reduce their risk of systemic disease. These therapies have significantly improved clinical outcomes but they can lead to biological changes that affect long-term vaginal health and impact quality of life in survivors. Pre- and postmenopausal women can experience symptoms of estrogen deprivation, including VVA[43], at higher rates than age-matched women without BC.

In a cohort of premenopausal BCSs receiving chemotherapy (CTx), vaginal dryness was reported by 23.4% of women[44]. CTx can promote a chemotherapy-induced ovarian failure (CIOF). The use of chemotherapy during the first year after the diagnosis of breast cancer significantly increases the risk of CIOF[45-47]. CIOF occurs secondary to CTx agents, which cause follicular destruction[45,47]. Consequently, decreases in the levels of estrogen and progesterone are observed. Forty- and fifty-year-old women undergoing CTx were found to have an increased risk of developing CIOF (40% and 90%, respectively) vs an increased risk of CIOF in healthy age-matched forty- and fifty-year-old women (< 5% and 20%, respectively)[47]. Postmenopausal women can also experience increased or recurrent symptoms of estrogen deprivation, depending on the amount of endogenous estrogen circulating in their system, including estrogen produced by the adrenal glands and estrogen stores in body fat.

A total of 70%-80% of all BCSs are estrogen receptor-positive[48]. Endocrine therapy is extremely successful in suppressing circulating estrogen, an effect desired for efficacy. Endocrine therapies for the management of breast cancer include aromatase inhibitors (AIs), tamoxifen (TAM) (a selective estrogen receptor modulator-SERM-) and fulvestrant. These drugs can trigger the onset of VVA or exacerbate existing symptoms[49].

Aromatase inhibitors: AIs are frequently prescribed for postmenopausal breast cancer patients[50,51]. Multiple clinical trials have shown that AIs have better clinical outcomes in these patients than SERM; thus, they have become the standard of care[50,51]. These drugs inhibit the activity of the enzyme aromatase, which is utilized to convert androgens to estrogens[52], and significantly reduce plasma concentrations of estrogen from 20 pmol/L to 3 pmol/L or less[35]. These changes explain the commonly reported side effects as vaginal dryness and decreased libido[35]. The increasing use of AIs over SERMs (including for premenopausal women in conjunction with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist- GnRH-a-) suggests that more women may experience new or increased atrophic vaginitis[35,50] than when TAM alone was used. Additionally, the recommended duration of these therapies has been extended from 5 to 10 years[53]. The severity of menopausal side effects, including VVA, may compromise compliance with AIs over time[54].

Tamoxifen: Tamoxifen (TAM) has been the most widely used traditional SERM and continues to be prescribed for premenopausal women with ER+BC[55]. TAM acts as an antagonist to estrogen positive breast cancer cells, although it often acts as an agonist to alfa estrogen receptors in the vagina. Hence TAM provides a quasi-estrogenic effect on the vulva and vagina and increases vaginal secretions without the presence of estrogen[35]. Due to its estrogenic effect, the incidence rate of vaginal dryness with TAM is only 8%, compared to 18% with AIs[35]. Therefore, this effect may inhibit the onset of atrophic vaginitis and actually improve existing vaginal dryness induced by CTx or menopause.

Fulvestrant: Fulvestrant is a competitive estrogen receptor antagonist that acts as an estrogen receptor downregulator, and is used in patients with metastatic BC[56]. Overall, six studies reported gynaecological toxicity (urinary tract infection, vulvovaginal dryness, vaginal haemorrhage, vaginitis, and pelvic pain) and no difference was observed between fulvestrant and control arms (RR 1.22, 95%CI 0.94 to 1.57; 2848 women; I2 = 66%; P = 0.01; high‐quality evidence)[57]. Because of its mechanism of action, rates of GSM may be less when compared with aromatase inhibitors[58] but higher than with tamoxifen therapy.

Vulvar and vaginal atrophy (VVA) are major components of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM). Symptoms of atrophic vaginitis include vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, irritation of genital skin, pruritus, burning, vaginal discharge, and soreness[19,41,59,60].

The related vaginal dryness and dyspareunia are chronic and progressively worsening conditions that affect quality of life (QoL) and intimate relationships in both healthy women and BCSs[36,61]. Atrophic vaginitis can disrupt sexual activity, and lead to problems such as pain with vaginal penetration (dyspareunia), decreased lubrication, and fear of pain with sexual activity[41]. Typical symptoms of atrophic vaginitis usually occur within 4-5 years after a woman’s last menstrual cycle[62], but women who undergo menopause at an accelerated rate (CTx, surgical removal or radiation therapy of the ovaries or anti-estrogen therapy) can experience earlier onset of GSM[31,32].

Atrophic vaginitis as a survivorship issue impacts women of all ages. Premature menopause with associated symptoms in young breast cancer survivors may have a profound negative impact on quality of life secondary to sexuality and intimacy changes[58]. Regardless, women of all ages seek to preserve their sexual function and improve their sexual quality of life[63,64]. Many young women are at increased risk for premature menopause following adjuvant treatment for BC. These women must deal with consequences of menopause, including loss of fertility and physiologic symptoms such as night sweats, hot flashes, vaginal dryness, and weight gain. These symptoms can be particularly distressing for young women and can adversely affect both health-related and psychosocial quality of life (QoL). BSC patients in Eastern countries are younger and more likely to have related problems. While there are a wide range of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions available to help with these symptoms and in turn, improve QoL, there is little data available about the use and efficacy of these interventions in younger women who become menopausal as a result of their breast cancer treatment. Consequently, it is suggested that future studies should focus on this vulnerable population, with the goal of identifying effective strategies to relieve symptoms and improve QoL in young BCSs.

Atrophic vaginitis is prevalent in women with and without breast cancer. Complaints of vaginal dryness were 67% vs 49%, fear of pain with vaginal penetration 31% vs 19% and irritation from toilet tissue 21% vs 9%, respectively[42].

Validating the effect of GSM on BCSs and the importance of seeking treatment for relieving symptoms and improving quality of life (QoL) is critical. Clinicians should explain the pathophysiology of GSM and review the potential genitourinary effects of breast cancer treatment[65,66]. Despite these bothersome symptoms, few women discuss them with their health-care professional or seek gynecological care[65], in part due to embarrassment, lack of knowledge, and an awareness of menopausal changes. The underdiagnosis and undertreatment of the condition lead to chronicity, disease progression and a considerable impact on women’s daily living, despite the currently available therapeutic options. Therefore, it is imperative that clinicians ask both partnered and unpartnered patients about potential physical changes and alterations that can be associated with atrophic vaginitis[5,66,67].

The simplest approach for clinicians to detect sexual problems related to GSM is to start a conversation with the woman when it feels relevant during the encounter. Clinicians can also ask a direct screening question such as, ‘Do you have any problems or concerns related to sex or pain with sexual activity?

There are readily available, simple, and effective tools for the identification of symptoms and assessment of the effect on QoL, including the Day-to-Day Impact of Vaginal Aging questionnaire[68] and the Sexual Symptom Checklist for Women After Cancer[69]. The structured approach to incorporating sexuality into clinical practice, devised specifically for patients with cancer, is The BETTER model (B - bringing up the topic, E - explaining the importance of sexuality, T - telling the patient about resources, T - addressing timing, E - educating about sexual side effects of treatment, and R - recording the discussion)[70].

It is important to gain a clear understanding of a woman’s genitourinary symptoms and how they affect her QoL and intimate relationship. In addition to a complete history, which includes review of potential medications that might cause vaginal dryness, women with genitourinary complaints should undergo a physical examination before starting treatment. The examination should include visual external inspection, speculum, and bimanual pelvic examination as clinically relevant and to exclude other conditions that might mimic GSM, such as vaginitis, lichen sclerosus, or other dermatopathology.

During an examination, the woman and clinician can review areas of concern, and women can be educated regarding anatomy and instructed in the application of local therapies, using a hand mirror as needed[65].

When assessing women with GSM with a history of breast cancer, it is important for the clinician to identify factors that may affect decision-making[71]. These factors include balancing the risk of recurrence, which is influenced by the stage and grade of the cancer; presence of lymphovascular invasion; hormone-receptor status; use of endocrine therapy; and the time since diagnosis, with the severity of genitourinary symptoms, QoL, and efficacy of conservative therapies. Although data are lacking, based on the consensus recommendations from The North American Menopause Society and The International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health, women with an overall lower risk of recurrence vs higher risk; with receptor-negative vs receptor-positive disease; using TAM vs AIs; and with severe symptoms and greater concerns about quality of life vs fewer symptoms and concerns may be better candidates for local hormone therapy[65].

Counseling patients with or at high risk of breast cancer about treatment options for GSM should include a shared decision-making approach employing the principles of informed consent[67]. The discussion about treatment options should include the mechanism of action, if known; potential adverse effects; current data regarding efficacy and safety; as well as the benefits and risks of each treatment option[72]. Clinicians should evaluate the woman’s perceived need for treatment vs fears regarding breast cancer risk or recurrence risk. Additionally, consultation with a woman’s oncology team is suggested[65,73,74]. A recent study found that 41% of breast oncologists refer BCSs to gynecologists for treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy, and 35% manage it independently. Seventy-one percent of oncologists mentioned that the main reason not to prescribe vaginal estrogen therapy is the probability of increased cancer recurrence[31].

Finally, when therapy is initiated, follow-up care should be arranged to ensure improvement in or resolution of symptoms and to assess compliance and barriers to treatment.

The growing awareness of quality-of-life issues in BCSs has done that management of GSM has been increasingly emphasized as a major problem that oncologist should know. The key is to determine the severity of the signs and symptoms of VVA and the degree of discomfort, tailoring the treatment to the individual needs of the patient.

The primary goal for the treatment of genitourinary symptoms is to improve or alleviate symptoms and to reverse the atrophic changes arising from estrogen deprivation[64,75]. Currently available treatments for GSM include both over-the-counter treatments (OTCs), such as nonhormonal vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, and prescription drugs, including local estrogen therapy (LET), intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), or systemic therapies. These prescription drugs aim to treat the underlying condition of GSM, while OTC drugs only treat the symptoms, such as vaginal dryness, itching, burning and dyspareunia. Ideally, the optimal therapy for estrogendeficiency symptoms is systemic or topical estrogen administration[76]. However, estrogen may be contraindicated in women with a history of hormone receptor-positive breast cancer[77]. As a result, patients and their clinicians are sometimes reluctant to use topical estrogens[78], and effective alternative approaches with nonhormonal lubricants and moisturizers are needed.

Clinician reluctance to treat may reflect the paucity of evidence regarding the safety of currently available therapies for GSM in women with or at high risk of breast cancer[79]. The unintended consequence is that women are driven to untested and non-FDA-approved therapies. In women with a history of breast cancer, the decision of how to treat GSM depends on many factors, including receptor status, genetic characteristics, extent of disease time interval since diagnosis, and response to prior therapies. Care for women with or at high risk of breast cancer would be enhanced by an evidence-based compilation of available GSM treatment options, along with a discussion of the limitations in the science concerning risks specific to this population[16,29,80].

According to international guidelines, nonhormonal therapies are the first-line treatment for mild-moderate VVA. Therefore, survivorship guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)/American Cancer Society (ACS)[81] and the North American Menopause Society[82] recommend the use of nonhormonal therapies, specifically water-or silicone-based lubricants and vaginal moisturizers, as first-line therapy for dyspareunia and vaginal dryness in BCSs. Severe signs or symptoms usually require pharmacological management (local hormonal therapy)[83].

Treatment of GSM in BCSs remains an area of unmet need. Vaginal estrogen is not generally advised, particularly for those on AIs, because it is absorbed in small amounts and raises blood levels within the normal postmenopausal period and could potentially stimulate occult breast cancer cells. The safety of intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone and oral ospemiphene after breast cancer has not been established. Vaginal laser therapy is being used for VVA in BCSs, but efficacy and safety data from clinical trials are lacking. Therapies such as lasofoxifene, neurokinin B inhibitors and stellate ganglion blockade are undergoing development[84]. To date, there is no consensus on how to treat moderate-severe GSM in BCSs.

As a first-line therapy for mild symptoms, lifestyle modifications (healthy diet, smoking cessation, losing weight, maintaining adequate vitamin D and calcium levels, limiting alcohol and regular physical activity) may be sufficient[85,86]. Smoking cessation may decrease the atrophic effects due to increased capillary refill[87], while weight loss of 5-10% of total body weight has been shown to improve urinary incontinence (UI)[88].

Sexual activity maintenance should also be encouraged. Regular coitus and masturbation can increase blood flow to the genital area, helping to keep this tissue healthy and maintaining normal vaginal pH[18,39,89]. Vaginal penetration with lubricated fingers or vaginal dilators may prevent fibrotic changes. Scented hygiene products should be avoided as they may reduce normal vaginal flora[18].

Women with pre-existing comorbidities (diabetes, obesity or hypertension) are more likely to develop VVA, UI and sexual dysfunction[90]. Thus, optimal management of these comorbidities may help to improve genitourinary and sexual health[90,91]. Furthermore, underlying depression treatment has been shown to improve both sexual functioning and quality of life (QoL) in breast cancer patients[92]. If an antidepressant is prescribed, an option that may be appropriate for TAM users is the SNRI venlafaxine, which increased libido in women with early breast cancer without interfering with the metabolism of TAM[93], or the SNRI desvenlafaxine[94]. Other options, given their minimal effect on sexual function and no appreciable inhibitory effect on CYP2D6, are mirtazapine and agomelatine[95,96].

Between 48%-83% of BCSs use at least one type of complementary or alternative therapy following diagnosis[97,98] despite limited evidence of the effectiveness/toxicity of these therapies in managing GSM in these patients[98-101]. This is important because at least half of breast cancer patients do not discuss their use of an alternative therapy with their clinicians[98,101]. Patients who use an alternative or complementary treatment should check with the manufacturer regarding whether the product contains estrogen or other hormones.

‘Natural products’: BCSs are very attracted to ‘natural’ products and generally have the impression that they are less toxic than conventional medicine[102]. In a clinical trial, dietary supplements with soy, black cohosh, and some other herbs did not show superiority over placebo in relieving a range of genitourinary symptoms[103].

Also, the safety of many of these products is unknown and there may be possible interactions with TAM and unknown effects on breast cancer cells[102]. Indeed, there is increasing concern about the lack of rigorous quality-control measures with regard to purity and levels of ‘active compound’ by some manufactures of herbal medicines as pointed out by the North American Menopause Society (NAMS)[103]. Clearly, there is the need in the long-term to investigate adequately designed RCTs to determine whether these products are of any help to breast cancer patients experiencing GSM-related symptoms. Most importantly, a risk assessment should be performed to help define their safety. Until such evidence- based data are available, their use merits caution[101].

Acupuncture and cognitive behavioral therapies: Stress management may be helpful in decreasing the anxiety associated with fear of painful intercourse[104,105]. There is very limited clinical data on the efficacy of acupuncture and behavioral interventions in the management of GSM in healthy women and none in BCSs. Acupuncture can decrease the urogenital subscale scores on the Menopause Rating Scale[106] and improve bladder capacity, urgency and frequency[107], but there are no evidence-based data[108]. In an RCT, cognitive behavioral therapy, physical exercise and a combination of both significantly decreased urinary symptoms and increased sexual activity in BCSs with treatment-induced menopausal symptoms compared to controls[109]. However, further studies are needed to recommend these treatments in BCSs.

Nonhormonal vaginal treatments: Lifestyle modification measures alone are usually insufficient to significantly improve atrophic vaginitis in BCSs. Nonhomonal vaginal therapies may provide additional treatment options to alleviate or improve vaginal dryness, irritation and itching by increasing vaginal moisture[104,105,110]. Local nonhormonal therapies include vaginal moisturizers, vaginal lubricants, vaginal pH-Balance Gel, vaginal autologous platelet-rich plasma (A-PRP) and avoidance of perfumed soaps and toilet tissue, rubber products, synthetic garments including panties, and certain fabric softeners[59]. Clinicians treating BCSs need to inquire about type and severity of their symptoms and the individual women’s expectations of treatment. So, if the most important concern for a woman is pain during intercourse, lubricants during sexual intimacy[110] may be recommended[78]. Additionally, adding vaginal moisturizers on a regular basis may promote hydration of the epithelium, providing more long-term (a few d) relief of symptoms such as itching, irritation and dyspareunia[111]. However, these therapies are not able to reverse atrophy once it occurs, and they may not completely solve the problem, especially in women with severe symptoms. Nevertheless, the evidence to support the efficacy of these formulations is limited (level II)[111]. Carter et al[112] (2011) developed a patient handout that summarizes how to best use vaginal lubricants, moisturizers and pelvic floor exercises.

According to international guidelines, nonhormonal therapies are the first-line treatment for mild-moderate VVA in both healthy women and BCSs[113]. According to a systematic review carried out this year (2021) by Mension et al[114] about current treatment options for genitourinary syndrome of menopause in BCSs, there are 10 studies related to nonhormonal options (excluding laser therapy) (4 prospective studies and 6 randomized controlled trials (RCTs)) (Table 1).

| Ref. | Yr | n1 | Design | Treatment | Conclusion |

| Loprinzi et al[119] | 1997 | 45 | A double-blind, crossover, randomized clinical trial | Vaginal lubricating preparation, (Replens®) | Both Replens and the placebo appear to substantially ameliorate vaginal dryness and dyspareunia in breast cancer survivors |

| Lee et al[129] | 2011 | 44 vs 42 | Randomised controlled trial, double blinded | pH balanced gel vs placebo for 12 wk | Vaginal pH balanced gel could relieve vaginal symptoms |

| Juraskova et al[137] | 2013 | 25 | Prospective, observational study | polycarbophil-based vaginal moisturizer + olive oil as a lubricant during intercourse | Significant improvements in dyspareunia, sexual function, and quality of life over time |

| Goetsch et al[130,131] | 2014 2015 | 46 | Double-blind rct | 4% aqueous lidocaine vs saline | Significative and safe reduction in dyspareunia |

| Hickey et al[128] | 2016 | In a single-center, randomized, double-blind, ab/ba crossover design | Water- vs silicone-based lubricants | Total sexual discomfort was lower after use of silicone-based lubricant than water-based | |

| Juliato et al[126] | 2017 | 25 vs 25 | Randomised trial | Polyacrylic acid vs lubricant | Polyacrylic acid was superior to lubricant |

| Marschalek et al[136] | 2017 | 11 vs 11 | Randomised controlled trial, double blinded pilot study | Vaginal lactobacillus capsules vs placebo | Lactobacillus improves microbiota in BCSs |

| Hersant et al[139] | 2018 | 20 | Prospective, comparative (before/after) pilot study | A-PRP and evaluated at 0,1,3 and 6 mo | A-PRP improves vaginal mucosa in 6 mo treatment according VHI criteria |

| Chatsiproios et al[125] | 2019 | 128 | Open, prospective, multicentre, observational study. | oil-in-water emulsion during 28 d | This treatment seems to improve VVA symptoms with a short treatment |

| Carter et al[122] | 2021 | 101 | Single-arm, prospective longitudinal trial | Hyaluronic acid (HLA) vaginal gel for 12 wk | HLA moisturization improved vulvovaginal health/sexual function of cancer survivors |

Vaginal moisturizers: Vaginal moisturizers intend to replace normal vaginal secretions and maintain tissue integrity, elasticity, and pliability and should be used on a regular basis independent of sexual activity[105].

Although there is limited data to support the efficacy of over-the-counter products[113,114], vaginal moisturizers and lubricants are considered the initial and mainstay treatment options for GSM in women with breast cancer[40], and they are widely used[18], particularly for women with mild symptoms and those who want to avoid local estrogens[18,40]. However, these products are poorly differentiated and characterized[112].

In GSM induced by oncology treatment and with menopausal hormone treatment (MHT) contraindications, everyday use of a paraben-free with acidic pH and low osmolality vaginal moisturizer is indicated[115].

A 12-wk multicenter RCT compared vaginal estradiol tablets vs vaginal moisturizers vs placebo. All three groups demonstrated similar reductions in the most bothersome symptoms, with no evidence for the superiority of vaginal moisturizers or 10-mcg vaginal estradiol tablets over placebo gel[116].

In some studies, polycarbophil-based nonhormonal moisturizers (Replens©) were demonstrated to be more effective than lubricants and even as effective as vaginal estrogen creams in improving vaginal moisture, fluid volume, pH, and elasticity, as well as reducing dryness, itching, and dyspareunia[117,118]. This effect is not sustained over time unless the moisturizer is used on a regular basis[117,118]. However, in a double-blind, crossover randomized controlled trial (RCT) assessing 45 BCSs with a history of vaginal dryness or itching, a polycarbophil-based vaginal moisturizer was no more effective than placebo in relieving vaginal dryness and dyspareunia[119].

Vaginal hyaluronic acid: Another non-hormonal option is hyaluronic acid vaginal gel. Hyaluronic acid (HLA) releases water molecules into the tissue, thus alleviating the dry state of the vagina and also plays a role in tissue repair. RCTs comparing hyaluronic acid with estrogen cream in postmenopausal women found that both significantly improved clinical symptoms of vaginal dryness in women without breast cancer[120]. Moreover, Jokar et al[121], in an RCT, found that improvement in urinary incontinence, dryness, the maturation index, and composite score of vaginal symptoms was better in the HLA group than in the estrogen cream group.

In a very recent prospective study (2021) including 101 postmenopausal patients with hormone receptor-positive breast and endometrial cancer, treatment with a hyaluronic acid vaginal gel for 12 wk. improved the vulvovaginal health/sexual function of cancer survivors. While HLA administration at 1-2×/week is recommended for women in natural menopause, a 3-5×/week schedule appeared to be more effective for symptom relief in cancer survivors[122]. One year earlier, these authors demonstrated that the HLA-based gel improved vulvovaginal health and sexual function in 43 endometrial cancer survivors in their perceived symptoms and clinical exam outcomes[123].

Vaginal lubricants: Lubricants (water-, glycerin- or silicone-based products) are designed to be applied during sexual activity, with direct application to the external genitalia, vaginal introitus, and vaginal mucosa to reduce friction and discomfort. Lubricants are shorter acting than moisturizers and have no effect on vaginal pH or underlying moisture content due to the ingredients and manufacturing of the product. The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests the use of lubricants with an osmolality of < 380 mOsm/kg, but most available lubricants do not list osmolality on the product label and have higher osmolality associated with mucosal irritation[117]. Lubricants with pH levels ≤ 3.0 are considered unacceptable for human use, given their association with vaginal irritation in animal models[124]. Additives (parabens, glycerin, flavors, and spermicides) should be avoided because they may irritate vaginal and vulvar tissues.

In dyspareunia induced by an oncology treatment and with MHT contraindicate, use of a paraben-free vaginal with acid pH and low osmolality lubricant during sexual intercourse is indicated[117].

In a prospective multicenter observational study by Chatsiproios et al[125], who evaluated the effect of an oil-in-water emulsion for 28 d in 128 patients diagnosed with BC and managed with chemotherapy or hormonal therapy, the authors concluded that there were improvements in symptom frequency after treatment and that the cream was an effective and safe nonhormonal topical option in the treatment of vulvovaginal dryness symptoms in patients undergoing breast cancer treatment. However, the study duration and follow-up time during 4 wk. as well as the non-randomized trial design are limitations of the study. The quality assessment (Qa) was fair.

Polyacrylic acid appeared to be superior to lubricants according to a randomized trial conducted by Juliato et al[126]. Fifty-two women (25 polyacrylic acid vs 25 Lubricant) with breast cancer who were being treated with TAM and who complained of vaginal dryness were evaluated. There was improvement in the female sexual function index (FSFI) after both treatments.

The polyacrylic acid group showed a decrease in sexual dysfunction from 96% to 24% (P < 0.0001) and the lubricant group showed a decrease from 88.9% to 55.6% (P = 0.0027). Polyacrylic acid was superior to the lubricant in treating sexual dysfunction [Qa = Good]. Products that contain glycerin may provide improved comfort during sexual activity as compared to water-based products. Silicone-based products may last longer than either water- or glycerin-based products. The ideal combination is to insert polycarbophil gels intravaginally 4-7 times per week, and utilize generous amounts of a glycerin-based vaginal lubricant before and during sexual activity[43]. This combination not reverse vaginal atrophy, but may provide additional short-term comfort during sexual activity.

Although the use of water-based lubricants are advised in cancer survivors[127], recent findings suggested that silicone-based lubricants may be more effective in treating discomfort during sexual activity in postmenopausal women with breast cancer, although both therapies were unlikely to reduce sexually-related distress[128].

Vaginal pH-balanced gel: A double-blinded RCT using vaginal pH-balanced gel in postmenopausal BCSs suffering from atrophic vaginitis was conducted in 2011. A total of 88 BCSs were randomly assigned to receive either pH-balanced gel (with lactic acid, pH 4 to 7.2) or placebo. The treatment was used three times per week for 12 wk. The pH-balanced gel provided significant (P = 0.001) improvements in vaginal dryness and dyspareunia compared to placebo and was effective in reducing the vaginal pH (P < 0.001). In addition, the pH-balanced gel enhanced vaginal maturation index (P < 0.001) and vaginal health index (P = 0.002). No significant difference in adverse events between the two gels was noted with minimal side effects (mild irritation during the first four wk. of therapy administration). These findings suggest that vaginal pH-balanced gel is an alternative option to alleviate vulvovaginal symptoms in symptomatic patients and can ultimately protect against vaginal colonization by nonvaginal microflora, which predisposes women to vaginal infections and UTIs[129].

Vulvar lidocaine: For women with pain isolated at the vulvar vestibule with penetration, topical lidocaine may provide relief[130]. A double-blinded RCT evaluating 4% aqueous lidocaine vs saline applied with a cotton ball to the vestibule for 3 minutes before vaginal penetration for insertional dyspareunia in 46 postmenopausal survivors of breast cancer with severe GSM for 4 wk. showed a significant reduction in dyspareunia of 88% vs 33% with saline (P = 0.007) and may be considered a safe option for painful intercourse in BCSs[131].

Vitamins E and D: Vaginal application of vitamin E capsules before intercourse increases vaginal lubrication and provides some atrophic-related symptom relief[100,132]. Oral vitamin D supplementation may help squamous maturation of the vaginal epithelium [133], but there were no significant improvements in vulvovaginal symptoms or pH[134]. The available evidence does not support the use of vitamins for relief of genitourinary symptoms[3].

Vaginal/oral probiotics: Oral and vaginal probiotics to change the vaginal microbiota could possibly be beneficial for the treatment of symptoms of GSM, but comprehensive trials are needed for validation[135]. A prospective, randomized, double-blinded trial (2017) evaluating new options, such as capsules including Lactobacillus, for the maintenance of the vaginal microbiota in women with breast cancer during chemotherapy was shown to be useful. The quality assessment (Qa) was good[136].

Olive oil, vaginal exercise, and moisturizer: The OVERcome study (Olive Oil, Vaginal Exercise, and Moisturizer) resulted in significant improvements in quality of life, sexual function, and dyspareunia (P < 0.001). Maximal benefits were noted after 12 wk. of intervention. However, the quality of this study was very poor, with only 25 breast cancer patients recruited[137]. There is concern regarding the use of natural oils (e.g., olive and coconut) for lubrication because these products are associated with vaginal infections[138].

Vaginal autologous platelet-rich plasma: Other recent options (2018) include autologous platelet-rich plasma (A-PRP), which was demonstrated in 20 patients with diagnosed BC, with a median age of 60.8 years, to improve vaginal mucosa following 6 mo. of treatment according to the Vaginal Health Index (10.7 to 20.75; P < 0.0001) in a prospective, comparative (before/after) pilot study [Qa = Fair][139].

Vaginal dilators: In addition to the use of vaginal moisturizers and lubricants, regular use of vaginal dilators has been recommended for symptomatic vaginal atrophy[40] and has been found to reduce pain with vaginal penetration by improving vaginal elasticity[140].

Patients should be counseled regarding the use of vaginal dilators of graduated sizes (either by themselves or with their partners) to promote stretching of vaginal tissues. Vibratory stimulation, applied either to the vagina or directly to the clitoris, has also been studied as a modality to reduce pain with vaginal penetration[141]. Finally, pelvic floor therapy under the care of a physical therapist trained in the management of pelvic floor disorders is recommended to reduce pain with vaginal penetration; physical therapists may also be helpful in the education of vaginal dilator therapy[142,143].

In summary, among nonhormonal therapies there are multiple options to treat symptoms of dyspareunia and daily wellbeing. However, these compounds do not reverse atrophy, and neither do they improve vaginal epithelium characteristics, and hence, the improvement observed is temporary and short term. These therapies are usually lubricants and moisturizer agents composed by non-hormonal substances, mainly based on water, silicone or vegetable oil. Water-based agents have fewer side effects compared to oil-based products[29].

The main limitation of non-hormonal therapies is the short-term efficacy. Among the trials included in this systematic review, 85% described efficacy with a 30-day follow-up or less. Further studies evaluating longer follow-up periods would be of interest.

The lack of data on hormonal receptor status and adjuvant treatments in the studies reviewed, as well as the absence of hormone levels and information about BC recurrence after treatment did not allow these trials to make conclusions in relation to safety. Nonetheless, from general population trials, it can be extrapolated that there is a low risk of potential side effects from nonhormonal therapies used for climacteric symptoms[144].

When nonhormonal methods fail in symptomatic survivors, local short-term hormonal therapy may be considered, following appropriate counseling and assessment of riskbenefits balance[145].

Whether the antiestrogen effect is induced by SERMs (tamoxifen or raloxifene) or by lowering endogenous estrogen production (e.g., bilateral oophorectomy, ovarian suppression with GnRH agonists, use of AIs), the goal of reducing the estrogen environment to lower breast cancer risk has remained the same. Therefore, both systemic and local estrogen-based treatments are controversial or discouraged for women with a history of or at high risk of breast cancer[81].

Systemic estrogen or estrogen/progestogen treatment: Healthy women can expect up to a 75% reduction in frequency and 87% reduction in severity of symptoms of GSM when prescribed systemic estrogen[146].

To date, there is a consensus in the literature that estrogen administration in BCSs or in women at high risk of BC should only be prescribed topically, since systemic administration has been shown to increase the risk of BC occurrence or recurrence[147] and is formally contraindicated by international guidelines (International Menopause Society-IMS)[148]. This consensus is supported by the results of two Swedish RCTs of systemic hormone therapy (HT) in survivors of early breast cancer. In 2001, the pivotal HABITS study (Hormonal Replacement Therapy After Breast Cancer—Is It Safe?) was conducted by Holmberg et al[149]. The authors studied the effects of systemic hormone replacement therapy on breast cancer recurrence among Scandinavian BCSs. A total of 434 women who had completed treatment of stage 0 to II breast cancer with symptoms of menopause were randomly assigned to receiving cyclic or continuous combination hormonal therapy (HT) with estradiol hemihydrates and norethisterone acetate. In 2003, it was prematurely stopped after a median follow-up of 2.1 years because of a statistically significant increased breast cancer recurrence in the HT group vs non- HT group (HR of 3.5 (95%CI, 1.5 to 8.1). The HABITS study showed that BCSs who received HT not only had a higher risk of breast cancer recurrence but also a higher risk of adverse events than BCS patients receiving the best symptomatic treatment without hormones. A four-year follow-up of the study sample found that women in the hormone replacement therapy group had twice the rate of a breast cancer event as compared to the control group (HR = 2.4).

Another RCT (The Stockholm trial)[150] also studied BCSs (n = 378) randomized to hormonal therapy or nonhormonal therapy for symptoms related to lack of estrogen. Hormonal therapy included cyclic estradiol and medroxyprogesterone acetate or estradiol valerate alone or non-HT. The trial, similar to HABITS, prematurely ceased due to safety concerns of breast cancer recurrence. In contrast to the HABITS trial, the Stockholm trial did not actually find an increase in breast cancer recurrence after a median follow-up period of 4.1 years in the hormone replacement study arm (HR = 0.82; 95%CI, 0.35 to 1.9). However, there was statistically significant (P = 0.02) heterogeneity in the rate of recurrence between the two studies, and the Stockholm trial investigators concluded that HT may be associated with the recurrence of breast cancer. On the basis of these studies, HT is currently contraindicated in BCSs because of an increased risk of breast cancer recurrence or new primary development.

Tibolone: Tibolone is a synthetic steroid that, after absorption, is rapidly converted to three active metabolites (with weak estrogenic, progesterogenic, and androgenic properties) that bind to estrogen receptors in the vagina. In a nonrandomized, open-label study of healthy postmenopausal women (n = 113), the use of tibolone over six years reversed vaginal atrophy and improved symptoms[151]. Later, tibolone was shown to improve vaginal dryness and may have a favorable effect on sexual function[152].

The Livial Intervention Following Breast Cancer; Efficacy, Recurrence and Tolerability Endpoints (LIBERATE) trial has been the most important study of the relationship between tibolone and BCSs[153,154]. This prospective randomized placebo controlled study was conducted to evaluate the safety of tibolone in BCSs (n = 3098) (1556 in the tibolone group and 1542 in the placebo group). The study showed that tibolone (2.5 mg) was effective in improving menopausal symptoms, including vaginal dryness and enhanced QoL in BCSs, but the trial was terminated early due to an increase in breast cancer-related events in the tibolone arm. After a median follow-up of 3.1 years, 237 of 1556 (15.2%) women on tibolone had a significantly increased risk of breast cancer recurrence compared with 165 of 1542 (10.7%) on placebo (HR 1.40 [95%CI 1.14-1.70]; P = 0.001). Therefore, the use of tibolone was contraindicated after breast cancer, with the authors warning that any off-label use incurred a now proven risk[154]. The IMS has supported this recommendation[155].

Bazedoxifene: Two RCTs provided data for consideration of bazedoxifene, a Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERM), combined with conjugated equine estrogens (BZA/CE) to treat symptoms of postmenopausal vulvovaginal atrophy. In the first study, healthy, postmenopausal, nonhysterectomized women (n = 652) with symptoms of moderate to severe vulvar/vaginal atrophy were randomized to different doses with BZA/CE or placebo. Treatment with BZA/CE for 12 wk. was shown to significantly improve sexual function and quality-of-life measures in symptomatic healthy postmenopausal women. As a single agent, bazedoxifene alone was not effective in relieving vulvovaginal symptoms. It remains unknown whether this combination will be safe and well tolerated in women with breast cancer[156].

Kagan et al[157] showed similar results in another RCT in which they concluded that BZA/CE was effective in treating moderate to severe VVA and vaginal symptoms. Because no studies have investigated drug safety in BCSs, it should not be recommended in these women.

Ospemifene: Ospemifene is a systemically administered SERM with therapeutic options for women with moderate-severe VVA and estrogen contraindications[82]. Comprehensive studies of ospemifene demonstrated an improvement in the vaginal maturation index and relief of most VVA symptoms in healthy women, as well as improvement in measures of sexual wellbeing[158]. At a dose of 60 mg per day, ospemifene significantly reduced the severity of dyspareunia, had a beneficial effect on vaginal dryness[159], improved vulvar vestibular symptoms and normalized the vulvar vestibular innervation sensitivity[160], and improved bone mineral density. The levels of estradiol remained within the normal postmenopausal range, with mean estradiol levels similar to baseline at week 12, and seemed to have an anti-estrogenic effect at the endometrial and breast levels[161]. It is approved by The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and by The European Medicine Agency (EMA). The NAMS recognize ospemifene as a nonestrogen therapy to improve vaginal symptoms of GSM and sexual dysfunction due to dyspareunia[82].

Coadministration of ospemifene with drugs that inhibit CYP3A4, CYP2C9 CYP2C19 may increase the risk of adverse reactions. Ospemifene has a good safety profile. The most common treatment-emergent adverse events in clinical trials were hot flushes (7.5% vs 2.6% for ospemifene vs placebo), vaginal discharge (3.7% vs 0.3%) and headache (3.1% vs 2.4%)[162]. The safety of using ospemifene concomitantly with estrogens or other SERMs, such as TAM (indicated for BC patients), has not been studied, and its concurrent use is not recommended. Therefore, ospemifene could be used for the treatment of VVA only once BC treatment, including adjuvant therapy, has been completed[82].

The most important property of ospemifene is that preclinical and clinical data demonstrated its antiestrogenic effect on breast tissue[163,164]. There are no clinical data showing that ospemifene would increase the risk of BC, and similar to other SERM, the data suggest that ospemifene acts as an antiestrogen in breast tissue and is more likely to have beneficial than detrimental effects[164]. However, the follow-up periods of these trials were too short to conclude the long-term effects of ospemifene[59,164].

Despite antiestrogenic effects on the breast in preclinical trials, the effects of ospemifene on breast density or breast cancer risk have not been systematically established in healthy women, nor has ospemifene been studied in women with breast cancer. Although it is not contraindicated for women in Europe with a history of breast cancer who have completed treatment[165], the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not recommend ospemifene for women at risk or with a history of BC or those with known or suspected estrogen-dependent neoplasia[82].

There are no differences in ospemifene-related improvements in symptoms of vulvar and vaginal atrophy in women with and without a history of BC[166], but there was a very small posthoc analysis in which is had an efficacy comparable to that of estrogenic treatments[167]. Bin Cai et al (2020)[168], in a retrospective matched cohort study, reported similar BC incidence rates per 1000 person-years of 2.03 (95%CI: 1.06-3.91) for treated patients and 3.53 (95%CI: 2.49-4.99) for controls (RR = 0.58, 95%CI: 0.28-1.21). Moreover, no difference in recurrence was observed between ospemifene-treated and matched untreated patients: 10 (32.3%) treated vs 25 (40.3%) controls in the 1:2 matched analysis.

According to the available evidence, ospemifene seems safer from the perspective of breast tissue. Therefore, it is a first-choice treatment in these cases at the end of adjuvant treatment until breast safety studies are conducted in which ospemifene will be directly compared to vaginal or systemic estrogens[167].

Information from three RCTs and one retrospective matched cohort study regarding systemic hormone treatment in BCSs is shown in Table 2.

| Ref. | Yr | n1 | Design | Treatment | Conclusion |

| Holmberg et al[147,149] | 2004 2008 | 221 vs 221 | Randomized, non-placebo-controlled noninferiority trial | Oral estradiol hemihydrate and Norethisterone (cyclic or continuous) vs control | In BCSs, an increased risk of new breast cancer events and adverse events were observed after 2 yr of therapy (HR = 2.4) |

| von Schoultz et al[150] | 2005 | 188 vs 190 | Randomized, non-placebo-controlled noninferiority trial | 2 mg estradiol for 21 d with addition of 10 mg medroxyprogesterone acetate for last 10 d; or 2 mg estradiol for 84 d with 20 mg medroxyprogesterone acetate for last 10 d; or 2 mg estradiol valerate daily | No increased risk of breast cancer recurrence; trial was closed early. So, HT doses of estrogen and progestogen and treatment regimens for menopausal hormone therapy may be associated with the recurrence of breast cancer |

| Kenemans et al[153] | 2009 | 1556 vs 1542 | Prospective randomized placebo controlled | Tibolone 2.5 mg daily or placebo | Trial was closed early. Tibolone had a significantly increased risk of breast cancer recurrence |

| Cai et al[168] | 2020 | 1728 vs 3456 | Retrospective matched cohort study | Incidence rate in ospemifene users vs untreated patients | No differences were observed in the BC incidence and recurrence rates in ospemifene users compared with matched controls |

Vaginal estrogens: The use of local hormone therapies (LHT) may be an option for some women who fail to resolve symptoms with nonpharmacologic and nonhormonal treatments after a discussion of risks and benefits plus review with an oncologist (Table 3).

| Ref. | Yr | n1 | Design | Treatment | Conclusion |

| Dew et al[178] | 2003 | 69 | Retrospective Cohort study | Estriol 0.5 mg cream and pessaries (33); Estradiol 25 μgtablets (n = 33) | VET does not seem to be associated with increased RR of BC |

| Kendall et al[190] | 2005 | 7 | Prospective before-after analysis | Estradiol 25 mg daily for 2 wk | Vaginal estradiol tablet significantly raises systemic estradiol levels. This reverses the estradiol suppression achieved by AIs in women with BC and is contraindicated |

| Biglia N et al[179] | 2010 | 26 | Prospective study | Estriol cream 0.25 mg (n = 10) or estradiol tablets 12.5 microg (n = 8) polycarbophil-based moisturizer 2.5 g (Replens®) (n = 8) | VET is effective in improving symptoms and objective evaluations in BCSs |

| Pfeifer et al[180] | 2011 | 10 | Prospective before-after analysis | 0.5 mg vaginal estriol daily for 2 wk | Increase in FHS and LH may indicate systemic estradiol effects |

| Whiterby et al[201] | 2011 | 21 | Phase I/II pilot Before-After study | Testosterone cream daily for 28 d. 300/ 150 μg | Vaginal testosterone was associated with improved signs and symptoms of vaginal atrophy related to AI therapy without increasing estradiol or testosterone levels |

| Wills et al[49] | 2012 | 24 vs 24 | Prospective clinical trial | 25 mcg estradiol vaginal tablet or ring vs control | VET treatment increases E2 levels. Should be used with caution |

| Le Ray et al[187] | 2012 | 13479TAM (n = 10806) or AIs (n = 2673) | Retrospective, nested case-control study | Vaginal cream and tablets containing estrogen | Use of VET is not associated with increase in BC recurrence in those treated with TMX or AI |

| Dahir et al[202] | 2014 | 13 | Pilot before-after study | Testosterone cream daily for 28 d, 300 μg | Improvement in FSFI scores |

| Donders et al[181] | 2014 | 16 | Open label bicentric phase I pharmacokinetic study | 0.03 mg Estriol + Lactobacillus | Estriol + Lactobacillusis safe in BCpatients andimprovessymptoms |

| Melisko et al[204] | 2016 | 69 | Randomised non-comparative study | Estradiol ring 7.5 ng vs Testosterone cream at 1% concentration: 1.5 mg/wk | Transient increase in E2 that finally reached normal levels. Meets the primary safety endpoint |

| Davis et al[203] | 2018 | 44 | Double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial | Testosterone cream daily for 26 week/ 300 μg vs placebo | Testosterone improves sexual test items compared to placebo |

Vaginal estrogen products are the most effective and sole intervention for menopausal symptoms limited to vaginal atrophy[19,50,64] compared to oral hormone menopausal therapy(HMT)[147].

A Cochrane review[169] of 30 randomized controlled trials of low to moderate quality including 6235 postmenopausal women showed that the local estrogenic preparations, in the form of creams, tablets and the estradiol-releasing vaginal ring, appeared to be equally effective in relieving the symptoms of VVA but there was a very small posthoc analysis in which is had an efficacy comparable, and a higher proportion of these women reported improvement in symptoms compared to those who received placebo. Also, adequate estrogen therapy act on the vaginal mucosa increasing its thickness, revascularizing the epithelium and increasing the number of superficial cells, thereby decreasing vaginal pH and restoring the vaginal microflora, increasing vaginal secretions, and decreasing vaginal dryness and resultant dyspareunia[76]. The evidence to support a role of systemic estrogen therapy in the management of urinary tract symptoms was conflicting according to a 2012 Cochrane review[170]. However, the authors suggested that the use of local (vaginal) estrogen therapy for incontinence may be beneficial (RR 0.74; 95%CI: 0.64-1.48), and less frequency and urgency were also reported[170].

Local therapies include estradiol-releasing intravaginal tablets, low-dose estrogen vaginal inserts, estrogen-based vaginal creams, and estradiol-releasing vaginal rings. All forms of vaginal estrogen therapies have similar rates of effectiveness but different levels of systemic absorption[171]. All preparations result in a minor degree of systemic absorption but do not exceed normal postmenopausal levels[172]. Vaginal estrogen absorption is variable and largely depends of potency of estrogenic ingredient, frequency and duration of use and also varies according to the condition of the vagina (atrophic vs estrogenized)[171]. The thin, atrophic vagina is highly absorptive, and this diminishes when the epithelium thickens in response to estrogenization of the vaginal mucosa[173]. In an atrophic mucosa, there is increased absorption, decreasing the level of estrogen absorbed once there is improvement in epithelium quality[174]. Whether a very small increase in estradiol exposure will stimulate quiescent, occult breast cancer cells or contribute to the development of breast cancer is not known. Preclinical data have shown that long-term estrogen deprivation can result in a state of estradiol hypersensitivity, to both proliferation and apoptosis[171], but it is not clear which effect would predominate.

The estrogen most commonly used in these preparations is estriol, which is a weak action estrogen. However, while clearance is more rapid, if used in a manner in which serum levels are consistently elevated, estriol can act as a systemic estrogen; therefore, the same cautions as with vaginal estradiol use are applied. Estriol vaginal preparations (gels, creams, and suppositories) are available in many countries but not in the United States. RCTs have found benefits for vaginal symptoms in healthy postmenopausal women[175]. Limited evidence reported in a small RCT suggested that 0.5 mg of vaginal estriol cream may also prevent recurrent urinary tract infection (UTIs)[176].

The use of estriol rather than estradiol has been suggested for BCSs since its metabolic clearance is more rapid[177]. Dew et al[178] in a retrospective cohort study with a follow-up of 5.5 years, administered estriol 0.5 mg cream and pessaries or estradiol 25 μg tablets in a study group of confirmed BC patients with VVA or without VVA as a control, among whom 48% were using TAM, and found that vaginal estrogen therapy does not seem to be associated with an increased relative risk (HR = 0.57; 95%CI: 0.20-1.58, P = 0.28) [Qa = Poor]. Biglia et al[179] in a prospective study (12 wk) with 31 postmenopausal BCSs not using AIs (TAM or Gn-RH analogs were permitted) and 18 receiving vaginal estrogen therapy (VET) (estriol 0.25 mg, estradiol 12.5 ng or 2.5 g Replens), concluded that VET was effective in improving symptoms and objective evaluations in BCSs, but they did not describe any results on safety [Qa = Good]. In a prospective, randomized study of 10 postmenopausal women with breast cancer who were taking AIs, a two-wk span of daily 0.5 mg vaginal estriol did not increase serum estrogen or estradiol levels but significantly decreased gonadotropin levels, indicating that the systemic effects have to be kept in mind when offering vaginal estriol to BCSs receiving an AI[180]. In one 12-week, open-label pilot study of 16 women with a history of breast cancer taking AIs, a 0.03 mg estriol tablet in combination with lactobacilli improved vaginal symptoms in 100% of patients (effective), and no changes in estradiol or estrona with a small transient increase in estradiol levels were found (safe) [Qa = poor][181,182]. Estriol is not FDA approved for any indication and must be used as an off-label hormone option.

There were no associations between the use of local low potency estrogen therapy and different breast cancer histologies, ductal or lobular, in a population-based case-control study. Only the estimates for tubular cancer were not significantly above unity, with no trend of increased estimates for longer vaginal estrogen use[183].

According to the current recommendations of the North American Menopause Society, the use of low-dose vaginal estrogen treatment is accepted if there is no improvement when using nonhormonal treatments in BCSs with VVA. The lowest effective dose must be administered, starting with the so-called “ultra-low-dose”, which has shown efficacy in healthy postmenopausal women[184]. However, the use of low-dose vaginal estrogen in BCSs receiving AIs has been discouraged by the American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology[81]. Therefore, currently there is some reluctance to use local estrogen therapy in BCSs because of its potential adverse effects, with up to 70% of oncologists managing BCSs not prescribing hormone therapies. There is fear of interferences with adjuvant treatments, such as TAM or AIs, which may result in an increased risk of BC recurrence[31].

Observational studies have suggested the relative safety of local estrogen treatment, although definitive placebo-controlled RCT data are lacking. A large Finnish observational study identified no elevated risk of de novo breast cancer associated with the use of vaginal ET[185]. Crandall et al, in 2018, reported no increased breast cancer risk in healthy participants in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) observational study despite a very large sample size and duration of follow-up[186].

The results of observational studies are reassuring, at least when vaginal estrogen was administered concurrently with TAM[178,187,188]. Therefore, vaginal estrogens may be appropriate for women with severe urogenital symptoms who use TAM because competitive interaction with the estrogen receptor prevents mild serum estradiol elevations from increasing the risk of breast cancer[189]. Le Ray et al[187] conducted a retrospective, nested case-control study of women with breast cancer (n = 13479) who used concomitant TAM (n = 1 0806) or AIs (n = 2673) and local estrogen. Overall, the risk of recurrence in cases treated with local estrogen was not increased compared to the control group (RR: 0.78, 95%CI,0.48-1.25). In stratified analyses, the risk was likewise not increased in those women on TAM (RR: 0.83, 95%CI,0.51-1.34). In women taking AIs, the risk was not estimable as no women experienced a recurrence. It is important to highlight the retrospective design and the short follow-up of 3.5 years of this trial, which may be too short to show survival outcomes, and thus, lead to uncertainty regarding the data.

Regarding the use of low-dose vaginal estradiol in BCSs receiving AIs, Kendall et al[190] in a prospective study, measured serum estrogen levels in patients on adjuvant AIs therapy for BC (n = 7) and using 25 mcg estradiol vaginal tablets for severe symptoms of atrophic vaginitis daily for 2 wk. At 2 wk of analysis, estradiol increased 83%, and at 10 wk., it increased by 66%. The authors concluded that vaginal estradiol tablets significantly raised systemic estradiol levels, at least in the short term. This effect would reverse the estradiol suppression achieved by AIs in women with breast cancer and is contraindicated [Qa = Fair]. Similarly, Wills et al[49], conducted a prospective clinical trial of postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer or at high risk of breast cancer (n = 24) who were taking AIs or SERM and VET (25 mcg estradiol vaginal tablet or ring) for ≥ 90 d for atrophic vaginitis and 24 controls taking AIs only. They concluded that VET, regardless of type, resulted in elevated circulating E2 Levels in this population, even with cornification of tissue, and should be used with caution [Qa = Fair]. Therefore, these studies do not provide robust evidence regarding the safety of vaginal estrogens in BCSs taking AIs, whose efficacy is due to markedly suppressed estrogen levels[49,190]. Nevertheless, Santen et al[191] reported that the increased levels of serum estradiol resulting from vaginal estrogen use may not exceed the normal range of postmenopausal serum estradiol. But, there is a lack of clarity regarding whether higher levels within a narrow postmenopausal range associate with increased risk for breast cancer recurrence, and similarly, whether lower levels are reassuring[49]. In addition, unmeasurable levels by commercially available estrogen assays can still mediate changes in distant tissues (i.e., bone or liver).

Conversely, Hirschberg et al[192], in sixty-one BCS patients receiving AIs (50 received estriol vaginal gel and 11 received placebo), found that ultra-low-dose 0.005% estriol vaginal gel showed efficacy in improving the symptoms and signs of vulvovaginal atrophy and that estriol levels increased initially and normalized by week 12, while estradiol and estrone remained mostly undetectable throughout the study. They concluded that the negligible impact of the product on the levels of estrogens, FSH, and LH supported the safe use of this ultra-low-dose estriol vaginal gel as a treatment option for vulvovaginal atrophy in BCSs receiving AIs [Qa = Good].

This year (2021), Streff et al[193] in a prospective trial to measure the change in blood estradiol levels in only 8 postmenopausal women with ER(+)-BC undergoing treatment with AIs when treated with vaginal estrogen preparation for their urogenital symptoms, found that there was no significant difference between the baseline and week 16 estradiol levels (P = 0.81). In addition, patients in the prospective group reported subjective improvement in their vaginal dryness symptoms questionnaires. Therefore, VET did not cause persistent elevations in serum estradiol levels and might be a safer option for women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer who have persistent urogenital symptoms [Qa = Poor].

In estrogen/progesterone negative tumors (ER-/PR-), the North American Menopause Society 2013 Position Statement[40] supports that topical vaginal estrogen can be prescribed. To date, there is no data that specifically separates groups of ER+PR+ or ER-PR- tumors in studies of the effectiveness, feasibility, or safety of estrogen in these groups. Based on the results of this review there is clear controversy on this topic, with some studies reporting no recurrence of BC, while others suggest caution due to a possible increase of serum estrogen levels that could lead to an increased risk of BC recurrence, specially in AIs users. Further studies are needed to evaluate these results.

In summary, taking into account the controversy, it is recommended that the risks and benefits be explained, individualizing each case with oncologists before using local estrogen therapies in BCSs. Without evidence to support value in clinical decision making, clinicians should be discouraged from measuring serum estrogen levels to assess systemic absorption of local estrogens as an indirect measure of risk for breast cancer recurrence[65].

BCS should use the lowest effective dose of vaginal estrogen as recommended by American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists[73], American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology[81], the Endocrine Society [72] and North American Menopause Society[82].

Vaginal promestriene: Promestriene (3-propyl ethyl, 17β-methyl estradiol) is a synthetic estrogen analog with reported minimal systemic absorption that has been suggested for topical treatment of vaginal atrophy. Low doses of topical vaginal estrogen therapy, because of its limited systemic absorption, are believed to have little or no effect on the breasts[194]. Therefore, as promestriene does not alter hormone levels, it should not modify the risk of breast cancer. Promestriene is an effective treatment for relieving the symptoms of VVA in BCSs with very poor vaginal absorption[195]. Furthermore, the absence of a systemic effect of promestriene has been confirmed with accurate and sensitive mass spectrometry and even after up to 4-6 mo. of therapeutic doses in clinical studies that included women with estrogen-sensitive malignancies[196].

Thus, it could be a first-line option for those who need minimal or ideally no vaginal absorption, particularly in symptomatic cancer patients. There are little data available in the literature, mostly consisting of small, open-label, short duration studies, and few RCTs. After a long-term market experience (almost 40 years), in 34 countries, and millions of pieces prescribed, the side effects were very rarely reported in pharmacovigilance data, whereas the effectiveness to relieve atrophy was good. To further improve the safety of promestriene, especially in estrogen-sensitive cancer patients, a very low dose is used from the beginning, starting with half or less of the usual dose, and then gradually increased until the minimum effective dose, which could further reduce its already minimal vaginal absorption[196]. However, in vitro studies[197] concluded that the potential estrogen-like properties of promestriene to stimulate the growth of estrogen receptor-responsive breast cancer cell lines, especially in estrogen-deprived conditions, suggest caution when prescribing for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal BCSs on AIs. Its ability to activate growth and gene expression in ER-BC cells warrants further study.

Vaginal testosterone: Other options, such as intravaginal androgens, are gaining attention as a potential treatment for VVA in BCSs, since androgen receptors have been identified in the vaginal mucosa[198].

In one trial, treatment of 80 healthy postmenopausal women for 12 wk with a compounded vaginal cream containing 300 mg of testosterone propionate improved vaginal signs and symptoms[199].

Testosterone administration at the vaginal level seemed to trigger the activation of estrogen and androgen receptors in the vaginal epithelium layers without activating estrogen receptors in other tissues due to the lack of aromatase at this level[200].

Testosterone can induce proliferation of the vaginal epithelium, but testosterone’s conversion to estrogen is blocked by AIs and therefore may be effective in reversing atrophic changes without raising circulating estrogen levels and compromising aromatase inhibitor therapy[201].

Up to 2020, three clinical trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of intravaginal testosterone (IVT) in BCSs were found[201-203] (Table 3). All were conducted in patients on adjuvant AI therapy for BC. The longest follow-up was 26 wk. Only one clinical trial by Witherby et al[201], with 21 BCSs, measured serum estradiol levels. They assessed the use of daily vaginal testosterone to treat vaginal atrophy in women with breast cancer receiving AIs. Testosterone cream in one of two dosages, 150 mcg (n = 10) or 300 mcg (n = 10) was applied to the inner labia minora, introitus, and internal vaginal mucosa for 28 d. Both dosages of testosterone improved symptoms of vaginal atrophy including dyspareunia (P = 0.001) and vaginal dryness (P < 0.001), although only the 300 mcg decreased vaginal pH (e.g., 5.5-5.0), and improved the vaginal maturation index (e.g., 20%-40%). This study did not show any significant elevation (P = 0.91) in serum estradiol levels (remained less than 8 pg/mL) at either dose of testosterone at 4 wk. of therapy. They concluded that a 4-wk course of vaginal testosterone was associated with improved signs and symptoms of vaginal atrophy related to AI therapy without increasing estradiol or testosterone levels, but longer-term trials are warranted.

Melisko et al[204] in a randomized, noncomparative trial, analyzed 69 patients on adjuvant AI therapy for BC who completed 12 wk. of estradiol ring 7.5 ng vs intravaginal testosterone cream at a 1% concentration 1.5 mg/week treatment. They found a persistent estradiol elevation in no women with vaginal estradiol ring and in 12% with IVT. Vaginal atrophy and sexual interest and dysfunction improved for all patients. This study supported the efficacy and safety of using intravaginal testosterone or estradiol-releasing vaginal rings in patients with breast cancer receiving AI therapy to treat vulvovaginal atrophy. However, persistent estradiol elevation was seen in the intravaginal testosterone group, suggesting that a lower dose of testosterone cream can be used. Therefore, the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health (ISSWSH) concluded that open-label studies that have used high doses of intravaginal testosterone in the presence of AIs for breast cancer have resulted in supraphysiological serum testosterone levels and have been reported to lower vaginal pH, improve the vaginal maturation index, and reduce dyspareunia[205].

Clinical use of vaginal testosterone therapies is limited because no currently available local (or systemic) testosterone formulations are FDA-approved for administration to women.