Published online Aug 15, 2014. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v5.i3.239

Revised: May 7, 2014

Accepted: May 28, 2014

Published online: August 15, 2014

Processing time: 280 Days and 5.4 Hours

Perianal symptoms are common in patients with Crohn’s disease and cause considerable morbidity. The etiology of these symptoms include skin tags, ulcers, fissures, abscesses, fistulas or stenoses. Fistula is the most common perianal manifestation. Multiple treatment options exist although very few are evidence-based. The phases of treatment include: drainage of infection, assessment of Crohn’s disease status and fistula tracts, medical therapy, and selective operative management. The impact of biological therapy on perianal Crohn’s disease is uncertain given that outcomes are conflicting. Operative treatment to eradicate the fistula tract can be attempted once infection has resolved and Crohn’s disease activity is controlled. The operative approach should be tailored according to the anatomy of the fistula tract. Definitive treatment is challenging with medical and operative treatment rarely leading to true healing with frequent complications and recurrence. Treatment success must be weighed against the risk of complications, specially anal sphincter injury. A full understanding of the etiology and all potential therapeutic options is critical for success. Multidisciplinary management of fistulizing perianal Crohn’s disease is crucial to improve outcomes.

Core tip: This manuscript is a comprehensive review that focuses on the multidisciplinary management of fistulizing perianal Crohn’s disease. The treatment options discussed in this review are based on a current literature review as well as our experience with the disease. Diagnostic and treatment algorithms are also provided.

- Citation: Sordo-Mejia R, Gaertner WB. Multidisciplinary and evidence-based management of fistulizing perianal Crohn’s disease. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2014; 5(3): 239-251

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5330/full/v5/i3/239.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4291/wjgp.v5.i3.239

Although Gabriel[1] first described patients with granulomatous perianal disease 17 years before the formal description of the disease by Burrill Crohn’s[2] in 1932, Bissell[3] was the first to describe the associated perianal manifestations of Crohn’s disease (CD). Furthermore, Morson et al[4] documented the appearance of perianal non-caseating granulomas and fistulas many years before the onset of intestinal CD.

The reported prevalence of anorectal involvement in patients with CD has varied but the most current population-based series have found involvement in 14 to 38 percent of patients[5-7], with isolated perianal disease seen in only five percent[8]. The prevalence of perianal manifestations increases as the disease progresses distally, with up to 92 percent of patients with CD involving the colon and rectum developing fistulas[9]. In most cases, bowel involvement precedes perianal disease[9], but up to 40 percent of patients can experience perianal symptoms before intestinal manifestations[10]. There does not seem to be a predilection for age but a younger age of onset increases the odds of developing perianal disease over time[11-12].

The most common presentation of perianal CD is abscess and fistula. However, patients with CD are frequently affected by other perianal pathologies including hemorrhoids, fissures, skin tags, ulcers, and strictures. Perianal CD has been associated with a disabling natural history[13], with common extraintestinal manifestations[14] and greater steroid resistance[15]. Perianal disease is often recurrent, with 35 to 59 percent of patients relapsing within two years[16]. More than 80 percent of patients require operative treatment, and up to 20 percent may require proctectomy[5,7]. Patients with perianal CD have also shown an increased risk for anal malignancies[17,18], with active and long duration of disease being identified risk factors[19-21].

The treatment of perianal CD continues to be a challenge, especially with the plethora of literature addressing both medical and operative treatment strategies. The purpose of this review is to summarize the efficacy of currently described methods for the management of fistulizing perianal CD and its complications.

Abscesses usually occur with active perianal CD with an incidence of up to 62 percent during the course of the disease[22]. Ischiorectal abscesses account for 40 percent of all perianal abscesses[23]. Fistula tract location can influence abscess development and transsphincteric fistulas pose the greatest risk[23].

Abscesses are uncommon with superficial fistula tracts. Makowiec et al[24] evaluated 61 patients with perianal CD and found that 73 percent of all abscesses were related to an ischiorectal fistula and 50 percent with a transsphincteric fistula. Recurrences occurred in 53 percent with a median time to recurrence of 14 mo. No patients with superficial fistula tracts had a second abscess, whereas about two thirds of patients with transsphincteric and ischiorectal fistulas recurred after 36 mo.

A detailed anorectal exam should be performed before any type of treatment is initiated. This frequently requires evaluation under anesthesia (EUA) with evaluation of the rectum to rule-out active disease. Perianal infection can occur in any anatomic plane (superficial, intersphincteric, ischiorectal, or supralevator), and requires immediate drainage and treatment of systemic symptoms with broad-spectrum antibiotics[6,25]. Many authors recommend drain placement or partial sphincter division to facilitate drainage, but these have not been associated with better outcomes[26,27]. In the setting of persistent perianal sepsis, imaging modalities such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) are used to guide the drainage of deep or complex abscesses[28,29].

When a fistula is encountered, a non-cutting seton should be placed to facilitate drainage and prevent recurrent infection, with improvement seen in 79 to 100 percent of patients[30-35]. Long-term drainage with non-cutting setons without definitive therapy has been reported to result in fistula recurrence in 20 to 80 percent of cases[33,36,37]. The combination of non-cutting setons and anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy has been associated with fistula healing rates of up to 67 percent and will be discussed below[38,39]. Fecal diversion to increase fistula healing and control perianal sepsis continues to be controversial with no level A data supporting its role but in the setting of persistent perianal sepsis, a temporary diverting stoma can be effective. Patients should be aware that these stomas are rarely reversed[40].

Cryptoglandular abscess/fistulas can and do occur in patients with CD and should be recognized as so because treatment differs. These abscess/fistulas tend to be superficial and are not associated with active anorectal CD; therefore, anti-TNF therapy is not indicated. Abscess drainage should follow the same principles as mentioned above. Placement of a non-cutting seton is encouraged and any attempt of local surgical treatment should take into consideration the patients underlying continence and CD status. Supplemental imaging studies, such as endoanal ultrasound (EAUS), are very helpful even when cryptoglandular etiology is suspected.

A population-based study[7] with up to 20 years of follow-up showed that one out every two patients with CD develop perianal fistulas. The etiology of perianal fistula formation in CD is not completely clear but genetic, microbiological, and immunological factors play a role. Most authors believe that fistulas originate either from the penetration of a rectal ulcer or from cryptitis spreading to the intersphincteric space. Intersphincteric and transsphincteric fistulas are the most common fistula tracts of cryptoglandular origin that occur in patients with CD. Suprasphincteric fistulas result from cryptoglandular disease or rectal ulceration, and extra sphincteric fistulas are frequently seen in patients with severe proctitis or iatrogenic injury.

At St. Marks Hospital, Tozer[41] studied biopsy samples from Crohn’s and idiopathic anal fistulas. Although immunological analysis showed no significant differences in interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, TNF, and interferon levels, CD patients had significantly higher interleukin 17 levels and significantly lower CD65 levels. The authors showed data suggesting aberrant expression of homing molecules on dendritic cells in Crohn’s anal fistulas suggesting a non-directed immune response, which may contribute to the pathophysiology.

Pelvic MRI is the preferred imaging study to assess fistulizing perianal disease. It has an accuracy of 90 percent for evaluating fistula tracts and of 97 percent for characterizing complex abscesses[42,43]. Furthermore, operative management may be altered in ten to 20 percent of patients by the addition of MRI to EUA, and this increases to up to 40 percent in patients with CD[44,45].

Once the anorectal disease is delineated, evaluation for proximal CD with endoscopy should also be considered. Although some studies have found an association between proximal fistulizing disease and perianal fistulas[46], other investigators have not observed this finding[47,48]. In patients with fistulizing perianal CD it is our practice to combine a pelvic MRI with EUA and rigid proctoscopy to evaluate for rectal inflammation.

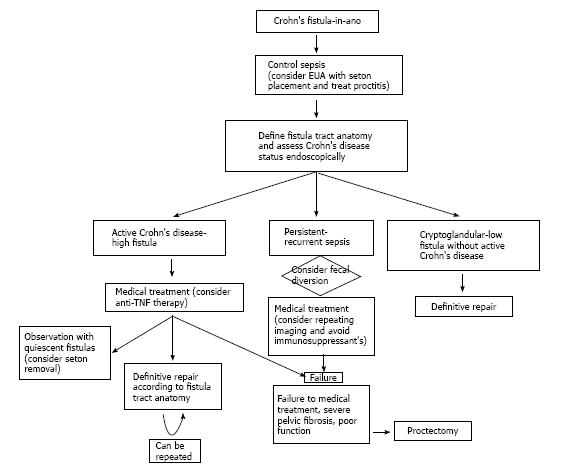

Once perianal infection is controlled, the fistula tract is characterized, and CD status is assessed; combined definitive medical and surgical therapy should be initiated (Figure 1). When active proctitis is encountered, this must be aggressively treated. Medical therapy includes antibiotics (metronidozole and ciprofloxacin), immunosuppressives (6-mercaptopurine, azathioprine, cyclosporine, and tacrolimus), and immunomodulators (infliximab, adalimumab, and certolizumab pegol). Although steroids are frequently used to manage concomitant luminal disease, there is no demonstrable role for corticosteroids in perianal CD. Medical treatment of perianal CD demands significant cooperation between gastroenterologists and surgeons as patient management is challenging and requires frequent feedback between medical professionals to optimize therapeutic strategies.

Antibiotics are commonly initiated when perianal infection is diagnosed and are frequently continued until immunosuppressive therapy is initiated[49], with 70 to 95 percent of patients having a positive response within six weeks[50,51]. It is our practice to continue antibiotic therapy for two weeks with perianal infection, and for three to four weeks with active proctitis. Metronidazole is the most common antibiotic prescribed for perianal CD and has been associated with fistula healing rates ranging from zero to 56 percent[50,52,53]. Seventy-five percent of patients relapse after suspending treatment and side effects which include nausea and peripheral neuropathy commonly limit its long-term use.

Ciprofloxacin has been studied in small, uncontrolled series of patients with perianal CD[54,55]. Improvement has been shown in approximately half of patients without detailed data on fistula healing. Ciprofloxacin was compared to metronidazole and placebo in a small randomized study including 25 patients[53]. After receiving treatment for ten weeks, clinical remission and response were 30 percent and 40 percent with ciprofloxacin, 12.5 percent and 12.5 percent with placebo, and 0 percent and 14 percent with metronidazole; none of these differences being significant.

The definitive medical treatment of perianal CD includes immunomodulation. A meta-analysis of five randomized controlled trials evaluated the efficacy of 6-mercaptopurine and azathioprine[56]. Fistula healing occurred in 54 percent of patients vs 21 percent of controls (OR 3.09; 95%CI, 2.45 to 3.91). Intravenous cyclosporine has also shown to have a good response in up to 83 percent of patients[57,58], but the effect is short-lasting when it is discontinued or transitioned to oral formulations[59]. Tacrolimus has also been effective in the treatment of perianal CD, as shown in one randomized controlled trial. Clinical improvement was seen in 43 percent of patients vs 8 percent receiving placebo (P = 0.004)[60].

Anti-TNF therapy, which includes monoclonal antibodies that are given intravenously [Infliximab (chimeric – murine/human)] or subcutaneously [Adalimumab and Certolizumab pegol (human)], has shown good results in the multidisciplinary management of perianal CD. Most patients who receive anti-TNF therapy receive concomitant immunomodulators. This combination has been poorly studied, specifically in perianal CD, but may be associated with less perianal complications and increased fistula healing[61]. What must be taken into consideration is that most studies evaluating anti-TNF therapy in the setting of perianal CD are of small numbers that involve heterogeneous patient groups with short follow-up. These studies also use varying definitions of fistula healing, disease improvement and “response”.

Infliximab alone: Present et al[62] reported that three infusions of infliximab resulted in closure of perianal fistulas in 46 percent of patients over 3 mo follow-up. A large study from Hungary including 148 patients with CD reported a perianal fistula closure rate of 49 percent at a mean of 3 mo follow-up[63]. A multicenter Italian study evaluating the impact of infliximab alone in 188 patients with perianal CD reported an initial response in 76 percent of patients with a 44 percent fistula closure rate[64]. Ng et al[65] prospectively evaluated the response to infliximab therapy with MRI in 34 patients with perianal Crohn’s fistulas. At six months, 58 percent of patients showed fistula closure, with 37 percent showing good clinical response.

Infliximab plus surgery: Regueiro et al[66] demonstrated an improved clinical response and less fistula recurrence when patients had EUA and seton placement before starting infliximab compared to patients who received infliximab alone. Topstad et al[38] also achieved improved outcomes with combined seton drainage, infliximab infusion, and immunosuppressives in 29 patients. At a mean follow-up of nine months, 67 percent of patients showed a complete response. Hyder et al[67] evaluated long-term healing rates with this approach in 22 patients. At a median follow-up of 21 mo, the authors only observed an 18% fistula closure rate. Van der Hagen et al[68] developed a multistep multidisciplinary approach that involved EUA with seton placement, fecal diversion when fistulas and abscesses recurred, infliximab therapy in case of persistent proctitis, and definitive fistula surgery. At a mean follow-up of 23 mo, fistula healing occurred in 90 percent of patients who received infliximab (9/10) compared to 71 percent in those who did not (5/7).

At the University of Minnesota, Gaertner et al[39] evaluated the outcomes of 226 patients who underwent operative treatment for perianal Crohn’s fistulas, with 79 of these patients also receiving preoperative infliximab. Fistula healing rates were similar regardless of infliximab therapy (59% vs 60%). However, patients who underwent surgery plus infliximab healed faster than those who did not receive infliximab (6.5 mo vs 12.1 mo; P < 0.0001), and seton placement plus infliximab infusion resulted in significantly improved fistula healing rates compared to seton placement alone (P = 0.001). Regardless of infliximab therapy, lay-open fistulotomy was the operation with the best healing rates. Active proctitis did not significantly impact healing after fistula surgery.

Adalimumab alone: Adalimumab has shown similar efficacy to infliximab in randomized controlled trials. In the CHARM (Crohn’s trial of the fully Human Antibody Adalimumab for Remission Maintenance) study, 113 patients with perianal Crohn’s fistulas received induction adalimumab; with subsequent maintenance adalimumab or placebo[69]. Evaluation at 26 wk showed complete fistula closure in 30 percent of patients treated with adalimumab, with improved outcomes at 56 wk compared to placebo (33% vs 13%). The durability of these results have been confirmed at two years follow-up[70]. In the CLASSIC-1 (Clinical Assessment of Adalimumab Safety and Efficacy Studied as an Induction Therapy in Crohn’s disease) trial, adalimumab was compared to placebo with the aim to evaluate short-term outcomes[71]. Thirty-two of 299 patients had perianal fistulas and no significant differences were observed in fistula healing.

Adalimumab has also been used in patients who have failed to respond to other anti-TNF agents, specially infliximab. In the GAIN (Gauging Adalimumab efficacy in Infliximab Nonresponders) trial, CD patients who were intolerant or who had lost response to infliximab received adalimumab or placebo[72]. Forty-five of 325 patients had perianal fistulas and no significant differences in fistula healing were found between placebo and adalimumab. Based on these results, most physicians consider that a second biological agent has minimal efficacy in patients who have already failed anti-TNF therapy.

Adalimumab plus surgery: As the experience with anti-TNF therapy expands, many authors have reported on a combined approach with adalimumab and local anorectal procedures. Tozer et al[73] reviewed the outcomes of 41 consecutive patients with fistulizing perianal CD treated with infliximab (n = 32) or adalimumab (n = 9), and followed radiologically with MRI. Fifty-eight percent of all patients (66% infliximab and 43% adalimumab) demonstrated remission or response at three years. Fistula healing, as demonstrated by MRI, lagged behind clinical healing by a median of 12 mo. All patients who achieved radiological healing maintained fistula closure while on anti-TNF therapy but only 43 percent maintained fistula closure after cessation of anti-TNF agents. El-Gazzaz et al[74] reviewed the Cleveland Clinic experience with combined anti-TNF therapy and anorectal surgery in 218 patients. Mean follow-up was 3.2 years. Two hundred and eighteen patients underwent operative treatment, 101 with anti-TNF therapy (74 infliximab and 27 adalimumab). Patient groups were comparable in demographic data and CD history but operative treatment was significantly heterogeneous. Patients who received combined anti-TNF therapy and surgery had significant overall improvement compared to patients who underwent surgery alone (36% vs 71%, P = 0.001).

Local anti-TNF therapy: Local injections of anti-TNF agents have also been attempted in fistulizing perianal CD, specifically in patients with contraindications to systemic treatment and resistance to infliximab. Poggioli et al[75] performed three to 12 local injections of infliximab (15-20 mg) adjacent to both internal and external openings and fistulous tract in 15 patients. Fistula closure occurred in ten patients at a mean follow-up of 18 mo. Asteria et al[76] achieved clinical response in six of eleven patients treated with local infliximab. Four of the eleven remained healed at a median of ten months of follow-up.

Tonelli et al[77] reviewed the outcomes of 12 patients with fistulizing perianal CD who underwent local injection of Adalimumab. Each patient received a median of seven (range, 4-16) injections. At a mean follow-up of 17.5 mo, 75 percent of patients (9 of 12) no longer had fistula drainage, and three patients (25%) showed clinical improvement. No adverse side effects were noted.

Certolizumab pegol: Certolizumab pegol is a humanized monoclonal antibody directed against TNF alpha. The antibody is fused with polyethylene glycol, which does not cross the placenta, so it should be safe in pregnancy. In 2008, the Food and Drug Administration approved Certolizumab pegol for the treatment of CD. Schreiber et al[78] evaluated its impact in patients with fistulizing CD. Patients with fistulizing CD from a randomized controlled study (PRECiSE 2, n = 108) comparing certolizumab pegol vs placebo were further randomized (if a good initial response was noted) to certolizumab pegol (n = 28) or placebo (n = 30) every four weeks until 24 wk. The majority of patients (55/58) had perianal fistulas. At week 26, fistula closure occurred in 36 percent of patients in the certolizumab pegol group compared to 17 percent of patients receiving placebo (P = 0.038).

If the attempt to heal a fistula has significant impact on a patient’s quality of life, operative treatment should be undertaken. Currently, the majority of operations for fistulizing perianal CD are performed in conjunction with medical therapy (immunomodulators or anti-TNF agents), and because this approach has been covered above, this section will focus on operative indications and efficacy of the most popular surgical techniques.

Most low, simple fistulas can be treated by fistulotomy. Healing rates from 80 to 100 percent have been reported with this technique[27,31,79,80]. Despite careful patient selection, an occasional fistulotomy wound may result in a chronic ulcer. In this situation, medical treatment is preferred as further operations have been associated with recurrent infection, fistula, and sphincter damage.

If partial sphincter division would compromise fecal continence, one can choose between minimally invasive techniques and anorectal repairs. Minimally invasive techniques include fibrin glue injection and collagen plug insertion. These techniques have no significant effect on fecal continence, are well tolerated by the patient, can be repeated, and are associated with fistula healing rates between 38 and 71 percent[81-84]. Fistula recurrence is common and occurs in approximately 50 to 70 percent of patients[81-84]. Video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT) and local injection of adipose-derived stem cells are recently described minimally invasive techniques that have been employed in patients with fistulizing perianal CD[85,86]. VAAFT involves performing fistuloscopy to identify the etiologic crypt and rule-out secondary tracts and then excise the internal opening. After this, the fistula tract is fulgurated. Stem cell therapy is a novel and promising approach for the treatment of chronic inflammatory conditions, and its use in fistulizing perianal CD has increased in Europe. Fistula healing rates between 30 and 82 percent have been reported with these techniques but the long-term safety and outcomes have not been adequately studied in the Crohn’s population. Overall, studies assessing the efficacy of minimally invasive techniques for Crohn’s perianal fistulas tend to be of small patient numbers, non-comparative and heterogeneous patient groups, retrospective nature, and with short duration of follow-up.

The most commonly employed anorectal operation for transsphincteric Crohn’s fistulas is a rectal advancement flap. This procedure has been associated with incontinence rates between five and nine percent but has not been associated with an increased risk for proctectomy[87]. Contraindications include significant proctitis, a cavitating ulcer or anal stenosis. Crohn’s fistula healing rates reported in the literature average 64 percent[87]. A recently described technique, ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) which involves the identification and ligation/transection of the fistula tract in the intersphincteric plane, is being increasingly employed in patients with transsphincteric Crohn’s fistulas[88]. This technique also has minimal to no repercussion on fecal continence but does involve a perianal wound. Although encouraging results have been reported in complex fistulas of cryptoglandular origin, experience in CD patients is limited[89,90].

In the setting of a large anal canal ulcer or severe stricture, an endorectal advancement flap can be performed in selective patients[91]. After the ulcer or stricture is excised, a full-thickness circumferential sleeve is mobilized and a formal rectoanal anastomosis is performed in combination with a diverting loop ileostomy.

After obstetric trauma, CD is the second most common cause of rectovaginal fistula (RVF)[92], occurring in five to 23 percent of CD patients[93-95]. The majority of RVF’s in the setting of CD are low and transsphincteric, and arise from rectal ulceration or infection of anterior anal glands[94,96].

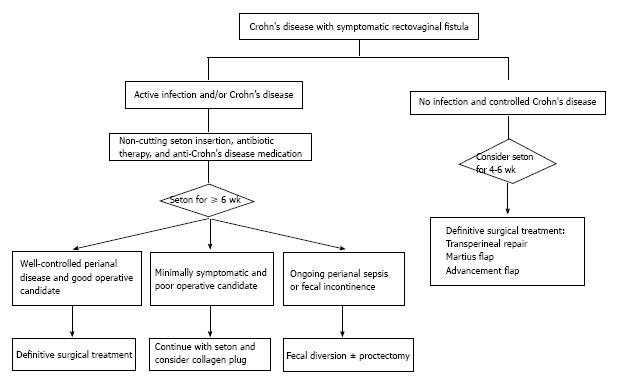

The management of RVF in CD is challenging. Treatment depends on the degree of symptoms, CD activity, and the anatomy of the fistulous tract (Figure 2). Minimally symptomatic patients may not require any treatment[7,94,97,98]. However, carefully selected symptomatic patients should be treated with a step-wise multidisciplinary approach. Drainage of local infection, seton placement and medical therapy are the initial steps before any attempts at fistula closure[92,94].

Patient selection is very important. Women with extensive anorectal CD are not good candidates for definitive fistula operations without first eradicating local infection and controlling the activity of underlying CD. Contrast to what has been reported in non-CD patients, a previous failed repair does not dictate a worse outcome with a subsequent operation. Healing rates reported after secondary operations are similar to those seen after a first attempt repair (29%-54%)[99-101]. Fecal diversion to protect a repair is also controversial. Penninckx et al[99] evaluated the impact of fecal diversion and parenteral nutrition in 32 consecutive patients undergoing RVF repair and did not find any significant role for either of these interventions. However, when O’Leary et al[102] selectively used fecal diversion in a step-wise approach that included initial seton placement and delayed repair, fistula healing occurred in 80 percent of patients. A diverting stoma does not ensure fistula healing and should only be performed in complex and recurrent cases.

Most of current treatment algorithms include combined medical and operative treatment. Present et al[103] found that 6-mercaptopurine was more effective than placebo, when combined with surgery (31% vs 6%). Most RVF’s recurred after discontinuation of 6-mercaptopurine. Similar results were observed with cyclosporine in two studies that included a total of six patients with RVF[104,105].

El-Gazzaz et al[106] evaluated long-term outcomes in 65 women with Crohn’s RVF´s who underwent a variety of different procedures. At a median follow-up of 47 mo, 46 percent healed. Multivariate analysis showed that immunomodulators were associated with successful healing (P = 0.009); and smoking and steroids were associated with failure (P = 0.04).

The efficacy of infliximab in RVF and CD has been controversial[38,62,66-68,107-109]. In the ACCENT II study[109], the initial response rate to infliximab was 64 percent. Rectovaginal fistula closure was maintained for longer with maintenance infliximab compared to placebo (46 wk vs 33 wk). Gaertner et al[110] reviewed the outcomes of 51 patients with Crohn’s RVF’s who underwent combined medical and operative treatment, 26 received preoperative infliximab. At a mean follow up of 38.6 mo, 27 fistulas (53%) healed. Transperineal repair was the operation with the highest healing rate regardless of infliximab therapy. Preoperative fecal diversion, active proctitis and infliximab therapy did not significantly impact fistula healing.

The definition of fistula healing tends to raise controversy when reviewing the RVF literature and seems to be influenced by the type of treatment, method of evaluation, and follow-up period. Rasul et al[111] assessed RVF healing by endoanal ultrasound in patients who clinically healed with infliximab therapy. Only five of 35 women demonstrated improvement but none showed fistula closure on ultrasound. Bell et al[112] found good correlation between clinical assessment and MRI in seven of ten patients treated with infliximab. Only two of these patients had RVF.

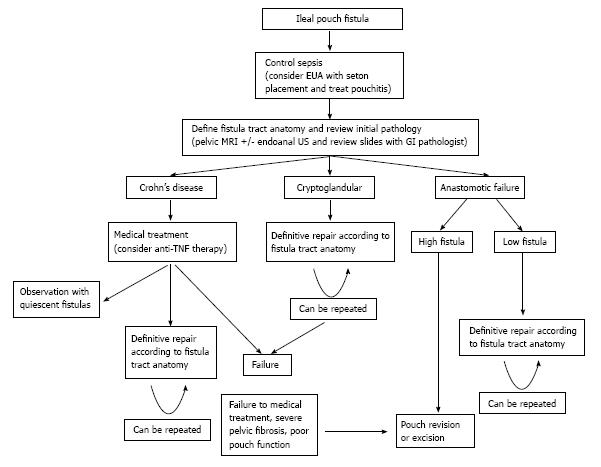

Patients who develop CD after restorative proctocolectomy with ileoanal anastomosis are at particularly high risk of developing pouch-anal fistulas. Although preoperative colorectal pathology, operative technique, and postoperative pelvic sepsis have also been identified as risk factors, CD is considered the most common[113-115]. Several operative techniques have been described to control pelvic and perianal sepsis and ultimately eliminate the fistula tract[116-120], but because of the low incidence of these fistulas, the optimal management continues to be controversial (Figure 3). Gaertner et al[121] reviewed the outcomes of 25 patients who presented with symptomatic ileal pouch fistulas over a 22-year period. Fistulas were classified as pouch-anal (48%), pouch-vaginal (28%), complex (16%), and pouch-perineal (8%). The most common etiology was CD. Overall fistula closure with a variety of local anorectal and abdominal procedures was 64 percent at a median follow-up of 29 mo. Postoperative pelvic sepsis, fecal diversion, and anti-TNF therapy did not significantly impact fistula healing. Three patients (12%) required pouch excision with end ileostomy.

In 1934, Rosser[122] first described carcinoma associated with a chronic perianal fistula. Fistula-associated adenocarcinoma is a rare but increasingly reported malignancy[18,21,123-131] that is commonly found in CD patients with chronic anal fistulas[18,21]. This malignancy is frequently associated with chronic, complex fistulas and can be particularly difficult to diagnose. High clinical suspicion is crucial to avoid any delay in diagnosis and treatment. Chronic infection and inflammation (i.e., CD and radiation) are the most frequently associated risk factors but even when the diagnosis is suspected clinically, confirmation requires EUA with biopsy. Misdiagnosis commonly occurs in elderly patients and patients with long-standing anorectal disease. Once the diagnosis of cancer has been established, EAUS and MRI are recommended for staging[132].

Mucinous adenocarcinoma is the most common malignancy reported in long-standing perianal fistulas. It is typically a slow growing, locally aggressive neoplasm that mainly spreads via the inguinal lymphatic’s[133]. Outcomes are good when malignancy is diagnosed early[131,133-136]. Oncologic resection remains the standard treatment option. Abdominoperineal resection is the most frequently employed operation[131,137,138]. The role of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in the treatment of this neoplasm has not been well studied, probably because of its rarity, but results are promising[21,131]. Neoadjuvant therapy may play a significant role to improve outcomes but remains investigational.

Gaertner et al[131] identified 14 patients with fistula-associated anal adenocarcinoma. The most common presentation was persistent perianal fistula (n = 9). Ten patients (71%) had CD. Abdominoperineal resection was performed in eleven patients, seven following neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. At a mean follow-up of 64 mo, ten patients were alive without evidence of disease and four patients died with metastatic disease. All seven patients who received neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy had a complete pathologic response. In a systematic review by Iesalnieks et al[21], a total of 23 publications including 65 patients with fistula-associated adenocarcinoma and CD were reviewed. Abdominoperineal resection was performed in 56 patients with an overall 3-year survival rate of 54 percent.

We recommend that tissue from refractory, recurrent and chronic anal fistula tracts, regardless of their etiology, should be submitted for pathologic evaluation. All patients with long-standing perianal CD should undergo cancer surveillance. Although the impact of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy remains controversial, oncologic resection continues to be the standard treatment option for fistula-associated adenocarcinoma.

Proctectomy is appropriate in patients in whom repeated medical and operative strategies fail. Historically, it is required in ten to 20 percent of patients with perianal CD[6], and is commonly associated with perineal wound breakdown, chronic open wounds and sinus formation in up to half of patients[139,140]. In our experience, intersphincteric proctectomy (when feasible) and the use of rectus abdominal and gracilis flaps can help with avoiding these complications.

A low Hartmann’s procedure is an alternative approach that may result in a healed perineum in up to 60 percent of patients with perianal CD[141]. Despite this approach, Guillem et al[142] reported a 54 percent completion proctectomy rate in 28 patients who underwent rectal exclusion, plus an additional nine patients had persistent active disease at the rectal stump.

The appropriate treatment of fistulizing perianal CD must be individualized to each patient. The primary goals are to ameliorate symptoms and prevent complications. Overall, a less aggressive approach is preferred as many patients will require repetitive operations that can often result in outcomes that are worse than the disease itself.

Based on the current literature, multidisciplinary treatment includes: eradication of infection, assessment of CD status and fistula tract(s), medical therapy, and selective operative management. The first phase of treatment is to drain the perianal infection. This typically involves an EUA, seton drainage and a short course of antibiotics. The second phase consists of endoscopically evaluating the extent of CD and delimiting the anatomy of the fistula tract with EUA and either EAUS or MRI, or both. During this phase, medical therapy with immunomodulators and anti-TNF agents is typically initiated but if the fistula is thought to be of cryptoglandular etiology, CD medications are rarely required.

The third phase should ideally involve healing of the perianal pathology. Many patients who have minimal symptoms elect to continue with a non-cutting seton or removal and expect healing in some cases. On many occasions a non-cutting seton may actually act as a cutting seton, specially in low superficial fistula tracts. The extensive range of operations highlights the complexity of operative treatment. These include a variety of minimally invasive techniques and anorectal operations. Sphincter injury and fecal incontinence should be the main concern with any anorectal operation. The operative approach depends on the anatomy of the fistula tract, CD status, and the patients’ functional status. Attempts to heal a fistula in the setting of active infection and proctitis are likely to fail. If the patient’s symptoms persist or increase despite adequate medical and surgical treatment, a diverting stoma or proctectomy should be considered.

P- Reviewer: Liu HM, Perakath B S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Gabriel WB. Results of an Experimental and Histological Investigation into Seventy-five Cases of Rectal Fistulæ. Proc R Soc Med. 1921;14:156-161. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Crohn BB, Ginzberg L, Oppenheimer GD. Regional ileitis: a pathologic and clinical entity. JAMA. 1932;99:1323. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1080] [Cited by in RCA: 809] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bissell AD. Localized Chronic Ulcerative Ileitis. Ann Surg. 1934;99:957-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Morson BC, Lockhart-Mummery HE. Anal lesions in Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 1959;2:1122-1123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hellers G, Bergstrand O, Ewerth S, Holmström B. Occurrence and outcome after primary treatment of anal fistulae in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1980;21:525-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 349] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sandborn WJ, Fazio VW, Feagan BG, Hanauer SB. AGA technical review on perianal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1508-1530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 435] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Schwartz DA, Loftus EV, Tremaine WJ, Panaccione R, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:875-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 739] [Cited by in RCA: 712] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lockhart-Mummery HE. Symposium. Crohn’s disease: anal lesions. Dis Colon Rectum. 1975;18:200-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Williams DR, Coller JA, Corman ML, Nugent FW, Veidenheimer MC. Anal complications in Crohn‘s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:22-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gray BK, Lockhartmummery HE, Morson BC. Crohn’s disease of the anal region. Gut. 1965;6:515-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cosnes J, Cattan S, Blain A, Beaugerie L, Carbonnel F, Parc R, Gendre JP. Long-term evolution of disease behavior of Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8:244-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 981] [Cited by in RCA: 979] [Article Influence: 42.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Roberts PL, Schoetz DJ, Pricolo R, Veidenheimer MC. Clinical course of Crohn‘s disease in older patients. A retrospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:458-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Beaugerie L, Seksik P, Nion-Larmurier I, Gendre JP, Cosnes J. Predictors of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:650-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 630] [Cited by in RCA: 639] [Article Influence: 33.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rankin GB, Watts HD, Melnyk CS, Kelley ML. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study: extraintestinal manifestations and perianal complications. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:914-920. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Gelbmann CM, Rogler G, Gross V, Gierend M, Bregenzer N, Andus T, Schölmerich J. Prior bowel resections, perianal disease, and a high initial Crohn’s disease activity index are associated with corticosteroid resistance in active Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1438-1445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Makowiec F, Jehle EC, Starlinger M. Clinical course of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1995;37:696-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sjödahl RI, Myrelid P, Söderholm JD. Anal and rectal cancer in Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis. 2003;5:490-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ky A, Sohn N, Weinstein MA, Korelitz BI. Carcinoma arising in anorectal fistulas of Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:992-996. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Connell WR, Sheffield JP, Kamm MA, Ritchie JK, Hawley PR, Lennard-Jones JE. Lower gastrointestinal malignancy in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1994;35:347-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Weedon DD, Shorter RG, Ilstrup DM, Huizenga KA, Taylor WF. Crohn’s disease and cancer. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:1099-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 340] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Iesalnieks I, Gaertner WB, Glass H, Strauch U, Hipp M, Agha A, Schlitt HJ. Fistula-associated anal adenocarcinoma in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1643-1648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wolff BG, Culp CE, Beart RW, Ilstrup DM, Ready RL. Anorectal Crohn’s disease. A long-term perspective. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:709-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Solomon MJ. Fistulae and abscesses in symptomatic perianal Crohn’s disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1996;11:222-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Makowiec F, Jehle EC, Becker HD, Starlinger M. Perianal abscess in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:443-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Singh B, McC Mortensen NJ, Jewell DP, George B. Perianal Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 2004;91:801-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Pritchard TJ, Schoetz DJ, Roberts PL, Murray JJ, Coller JA, Veidenheimer MC. Perirectal abscess in Crohn’s disease. Drainage and outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:933-937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sohn N, Korelitz BI, Weinstein MA. Anorectal Crohn’s disease: definitive surgery for fistulas and recurrent abscesses. Am J Surg. 1980;139:394-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Giovannini M, Bories E, Moutardier V, Pesenti C, Guillemin A, Lelong B, Delpéro JR. Drainage of deep pelvic abscesses using therapeutic echo endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2003;35:511-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Schratter-Sehn AU, Lochs H, Vogelsang H, Schurawitzki H, Herold C, Schratter M. Endoscopic ultrasonography versus computed tomography in the differential diagnosis of perianorectal complications in Crohn’s disease. Endoscopy. 1993;25:582-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Williams JG, Rothenberger DA, Nemer FD, Goldberg SM. Fistula-in-ano in Crohn’s disease. Results of aggressive surgical treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:378-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Halme L, Sainio AP. Factors related to frequency, type, and outcome of anal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:55-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sangwan YP, Schoetz DJ, Murray JJ, Roberts PL, Coller JA. Perianal Crohn’s disease. Results of local surgical treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:529-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Faucheron JL, Saint-Marc O, Guibert L, Parc R. Long-term seton drainage for high anal fistulas in Crohn’s disease--a sphincter-saving operation? Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:208-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Pearl RK, Andrews JR, Orsay CP, Weisman RI, Prasad ML, Nelson RL, Cintron JR, Abcarian H. Role of the seton in the management of anorectal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:573-577; discussion 573-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Thornton M, Solomon MJ. Long-term indwelling seton for complex anal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:459-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Buchanan GN, Owen HA, Torkington J, Lunniss PJ, Nicholls RJ, Cohen CR. Long-term outcome following loose-seton technique for external sphincter preservation in complex anal fistula. Br J Surg. 2004;91:476-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Eitan A, Koliada M, Bickel A. The use of the loose seton technique as a definitive treatment for recurrent and persistent high trans-sphincteric anal fistulas: a long-term outcome. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1116-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Topstad DR, Panaccione R, Heine JA, Johnson DR, MacLean AR, Buie WD. Combined seton placement, infliximab infusion, and maintenance immunosuppressives improve healing rate in fistulizing anorectal Crohn’s disease: a single center experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:577-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Gaertner WB, Decanini A, Mellgren A, Lowry AC, Goldberg SM, Madoff RD, Spencer MP. Does infliximab infusion impact results of operative treatment for Crohn’s perianal fistulas? Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1754-1760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Edwards CM, George BD, Jewell DP, Warren BF, Mortensen NJ, Kettlewell MG. Role of a defunctioning stoma in the management of large bowel Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1063-1066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Tozer P. Dendritic cell homing and immune cell function in Crohn’s anal fistulae. Gut. 2011;60:A220-1. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 42. | Buchanan GN, Halligan S, Bartram CI, Williams AB, Tarroni D, Cohen CR. Clinical examination, endosonography, and MR imaging in preoperative assessment of fistula in ano: comparison with outcome-based reference standard. Radiology. 2004;233:674-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Schaefer O, Lohrmann C, Langer M. Assessment of anal fistulas with high-resolution subtraction MR-fistulography: comparison with surgical findings. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2004;19:91-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Beets-Tan RG, Beets GL, van der Hoop AG, Kessels AG, Vliegen RF, Baeten CG, van Engelshoven JM. Preoperative MR imaging of anal fistulas: Does it really help the surgeon? Radiology. 2001;218:75-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Buchanan GN, Halligan S, Williams AB, Cohen CR, Tarroni D, Phillips RK, Bartram CI. Magnetic resonance imaging for primary fistula in ano. Br J Surg. 2003;90:877-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Sachar DB, Bodian CA, Goldstein ES, Present DH, Bayless TM, Picco M, van Hogezand RA, Annese V, Schneider J, Korelitz BI. Is perianal Crohn’s disease associated with intestinal fistulization? Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1547-1549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Marks CG, Ritchie JK, Lockhart-Mummery HE. Anal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 1981;68:525-527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Orkin BA, Telander RL. The effect of intra-abdominal resection or fecal diversion on perianal disease in pediatric Crohn’s disease. J Pediatr Surg. 1985;20:343-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Dejaco C, Harrer M, Waldhoer T, Miehsler W, Vogelsang H, Reinisch W. Antibiotics and azathioprine for the treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:1113-1120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Bernstein LH, Frank MS, Brandt LJ, Boley SJ. Healing of perineal Crohn’s disease with metronidazole. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:599. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Turunen UM, Färkkilä MA, Hakala K, Seppälä K, Sivonen A, Ogren M, Vuoristo M, Valtonen VV, Miettinen TA. Long-term treatment of ulcerative colitis with ciprofloxacin: a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1072-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Brandt LJ, Bernstein LH, Boley SJ, Frank MS. Metronidazole therapy for perineal Crohn’s disease: a follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:383-387. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Thia KT, Mahadevan U, Feagan BG, Wong C, Cockeram A, Bitton A, Bernstein CN, Sandborn WJ. Ciprofloxacin or metronidazole for the treatment of perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:17-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Turunen U, Farkkila M, Seppala K. What is New and What is Established in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Proceedings of the Athens International Meeting on Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Athens, 19–23 April, 1989. Longterm treatment of peri-anal or fistulous Crohn’s disease with ciprofloxacin. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24:144. |

| 55. | Solomon M, McLeod R, O’Connor B, Steinhart A, Greenberg G, Cohen Z. Combination ciprofloxacin and metronidazole in severe perineal Crohn’s disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 1993;7:571-573. |

| 56. | Pearson DC, May GR, Fick GH, Sutherland LR. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine in Crohn disease. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:132-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 721] [Cited by in RCA: 628] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Hinterleitner TA, Petritsch W, Aichbichler B, Fickert P, Ranner G, Krejs GJ. Combination of cyclosporine, azathioprine and prednisolone for perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Z Gastroenterol. 1997;35:603-608. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Egan LJ, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ. Clinical outcome following treatment of refractory inflammatory and fistulizing Crohn’s disease with intravenous cyclosporine. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:442-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Gurudu SR, Griffel LH, Gialanella RJ, Das KM. Cyclosporine therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: short-term and long-term results. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29:151-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Sandborn WJ, Present DH, Isaacs KL, Wolf DC, Greenberg E, Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Mayer L, Johnson T, Galanko J. Tacrolimus for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:380-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Sokol H, Seksik P, Carrat F, Nion-Larmurier I, Vienne A, Beaugerie L, Cosnes J. Usefulness of co-treatment with immunomodulators in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with scheduled infliximab maintenance therapy. Gut. 2010;59:1363-1368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, Hanauer SB, Mayer L, van Hogezand RA, Podolsky DK, Sands BE, Braakman T, DeWoody KL. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1398-1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1969] [Cited by in RCA: 1839] [Article Influence: 70.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Miheller P, Lakatos PL, Horváth G, Molnár T, Szamosi T, Czeglédi Z, Salamon A, Czimmer J, Rumi G, Palatka K. Efficacy and safety of infliximab induction therapy in Crohn’s Disease in Central Europe--a Hungarian nationwide observational study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Orlando A, Colombo E, Kohn A, Biancone L, Rizzello F, Viscido A, Sostegni R, Benazzato L, Castiglione F, Papi C. Infliximab in the treatment of Crohn’s disease: predictors of response in an Italian multicentric open study. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:577-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Ng SC, Plamondon S, Gupta A, Burling D, Swatton A, Vaizey CJ, Kamm MA. Prospective evaluation of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy guided by magnetic resonance imaging for Crohn’s perineal fistulas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2973-2986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Regueiro M, Mardini H. Treatment of perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease with infliximab alone or as an adjunct to exam under anesthesia with seton placement. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2003;9:98-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Hyder SA, Travis SP, Jewell DP, McC Mortensen NJ, George BD. Fistulating anal Crohn’s disease: results of combined surgical and infliximab treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1837-1841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | van der Hagen SJ, Baeten CG, Soeters PB, Russel MG, Beets-Tan RG, van Gemert WG. Anti-TNF-alpha (infliximab) used as induction treatment in case of active proctitis in a multistep strategy followed by definitive surgery of complex anal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: a preliminary report. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:758-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, Hanauer SB, Panaccione R, Schreiber S, Byczkowski D, Li J, Kent JD. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn’s disease: the CHARM trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:52-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1598] [Cited by in RCA: 1620] [Article Influence: 90.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Colombel JF, Schwartz DA, Sandborn WJ, Kamm MA, D’Haens G, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, Panaccione R, Schreiber S, Li J. Adalimumab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2009;58:940-948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak RN, Lukas M, MacIntosh D, Panaccione R, Wolf D, Pollack P. Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn’s disease: the CLASSIC-I trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:323-333; quiz 591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1153] [Cited by in RCA: 1194] [Article Influence: 62.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, Hanauer SB, Colombel JF, Panaccione R, D’Haens G, Li J, Rosenfeld MR, Kent JD. Adalimumab induction therapy for Crohn disease previously treated with infliximab: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:829-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 706] [Cited by in RCA: 731] [Article Influence: 40.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Tozer P, Ng SC, Siddiqui MR, Plamondon S, Burling D, Gupta A, Swatton A, Tripoli S, Vaizey CJ, Kamm MA. Long-term MRI-guided combined anti-TNF-α and thiopurine therapy for Crohn’s perianal fistulas. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1825-1834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | El-Gazzaz G, Hull T, Church JM. Biological immunomodulators improve the healing rate in surgically treated perianal Crohn’s fistulas. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:1217-1223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Poggioli G, Laureti S, Pierangeli F, Rizzello F, Ugolini F, Gionchetti P, Campieri M. Local injection of Infliximab for the treatment of perianal Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:768-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Asteria CR, Ficari F, Bagnoli S, Milla M, Tonelli F. Treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease by local injection of antibody to TNF-alpha accounts for a favourable clinical response in selected cases: a pilot study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1064-1072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Tonelli F, Giudici F, Asteria CR. Effectiveness and safety of local adalimumab injection in patients with fistulizing perianal Crohn’s disease: a pilot study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:870-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Schreiber S, Lawrance IC, Thomsen OØ, Hanauer SB, Bloomfield R, Sandborn WJ. Randomised clinical trial: certolizumab pegol for fistulas in Crohn’s disease - subgroup results from a placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:185-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Fry RD, Shemesh EI, Kodner IJ, Timmcke A. Techniques and results in the management of anal and perianal Crohn’s disease. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989;168:42-48. [PubMed] |

| 80. | Levien DH, Surrell J, Mazier WP. Surgical treatment of anorectal fistula in patients with Crohn’s disease. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989;169:133-136. [PubMed] |

| 81. | Lindsey I, Smilgin-Humphreys MM, Cunningham C, Mortensen NJ, George BD. A randomized, controlled trial of fibrin glue vs. conventional treatment for anal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1608-1615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Grimaud JC, Munoz-Bongrand N, Siproudhis L, Abramowitz L, Sénéjoux A, Vitton V, Gambiez L, Flourié B, Hébuterne X, Louis E. Fibrin glue is effective healing perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2275-2281, 2281.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Vitton V, Gasmi M, Barthet M, Desjeux A, Orsoni P, Grimaud JC. Long-term healing of Crohn’s anal fistulas with fibrin glue injection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1453-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | O’Riordan JM, Datta I, Johnston C, Baxter NN. A systematic review of the anal fistula plug for patients with Crohn’s and non-Crohn’s related fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:351-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | de la Portilla F, Alba F, García-Olmo D, Herrerías JM, González FX, Galindo A. Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived stem cells (eASCs) for the treatment of complex perianal fistula in Crohn’s disease: results from a multicenter phase I/IIa clinical trial. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:313-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Schwandner O. Video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT) combined with advancement flap repair in Crohn’s disease. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:221-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Soltani A, Kaiser AM. Endorectal advancement flap for cryptoglandular or Crohn’s fistula-in-ano. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:486-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Vergara-Fernandez O, Espino-Urbina LA. Ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract: what is the evidence in a review? World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6805-6813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Abcarian AM, Estrada JJ, Park J, Corning C, Chaudhry V, Cintron J, Prasad L, Abcarian H. Ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract: early results of a pilot study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2012;55:778-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Ellis CN. Outcomes with the use of bioprosthetic grafts to reinforce the ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (BioLIFT procedure) for the management of complex anal fistulas. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:1361-1364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 91. | Marchesa P, Hull TL, Fazio VW. Advancement sleeve flaps for treatment of severe perianal Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1695-1698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Saclarides TJ. Rectovaginal fistula. Surg Clin North Am. 2002;82:1261-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Platell C, Mackay J, Collopy B, Fink R, Ryan P, Woods R. Anal pathology in patients with Crohn’s disease. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996;66:5-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Radcliffe AG, Ritchie JK, Hawley PR, Lennard-Jones JE, Northover JM. Anovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:94-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Galandiuk S, Kimberling J, Al-Mishlab TG, Stromberg AJ. Perianal Crohn disease: predictors of need for permanent diversion. Ann Surg. 2005;241:796-801; discussion 801-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | McClane SJ, Rombeau JL. Anorectal Crohn’s disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81:169-183, ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Tuxen PA, Castro AF. Rectovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1979;22:58-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Morrison JG, Gathright JB, Ray JE, Ferrari BT, Hicks TC, Timmcke AE. Results of operation for rectovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:497-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Penninckx F, Moneghini D, D’Hoore A, Wyndaele J, Coremans G, Rutgeerts P. Success and failure after repair of rectovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease: analysis of prognostic factors. Colorectal Dis. 2001;3:406-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Lowry AC, Thorson AG, Rothenberger DA, Goldberg SM. Repair of simple rectovaginal fistulas. Influence of previous repairs. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:676-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | MacRae HM, McLeod RS, Cohen Z, Stern H, Reznick R. Treatment of rectovaginal fistulas that has failed previous repair attempts. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:921-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | O’Leary DP, Milroy CE, Durdey P. Definitive repair of anovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1998;80:250-252. [PubMed] |

| 103. | Present DH, Korelitz BI, Wisch N, Glass JL, Sachar DB, Pasternack BS. Treatment of Crohn’s disease with 6-mercaptopurine. A long-term, randomized, double-blind study. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:981-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 802] [Cited by in RCA: 706] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Present DH, Lichtiger S. Efficacy of cyclosporine in treatment of fistula of Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:374-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Hanauer SB, Smith MB. Rapid closure of Crohn’s disease fistulas with continuous intravenous cyclosporin A. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:646-649. [PubMed] |

| 106. | El-Gazzaz G, Hull T, Mignanelli E, Hammel J, Gurland B, Zutshi M. Analysis of function and predictors of failure in women undergoing repair of Crohn’s related rectovaginal fistula. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:824-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Talbot C, Sagar PM, Johnston MJ, Finan PJ, Burke D. Infliximab in the surgical management of complex fistulating anal Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:164-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Van Assche G, Vanbeckevoort D, Bielen D, Coremans G, Aerden I, Noman M, D’Hoore A, Penninckx F, Marchal G, Cornillie F. Magnetic resonance imaging of the effects of infliximab on perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:332-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, Chey WY, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Kamm MA, Korzenik JR, Lashner BA, Onken JE. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1581] [Cited by in RCA: 1553] [Article Influence: 74.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Gaertner WB, Madoff RD, Spencer MP, Mellgren A, Goldberg SM, Lowry AC. Results of combined medical and surgical treatment of recto-vaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:678-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Rasul I, Wilson SR, MacRae H, Irwin S, Greenberg GR. Clinical and radiological responses after infliximab treatment for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:82-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Bell SJ, Halligan S, Windsor AC, Williams AB, Wiesel P, Kamm MA. Response of fistulating Crohn’s disease to infliximab treatment assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:387-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Meagher AP, Farouk R, Dozois RR, Kelly KA, Pemberton JH. J ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis: complications and long-term outcome in 1310 patients. Br J Surg. 1998;85:800-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 402] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Fleshman JW, Cohen Z, McLeod RS, Stern H, Blair J. The ileal reservoir and ileoanal anastomosis procedure. Factors affecting technical and functional outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:10-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Keighley MR, Grobler SP. Fistula complicating restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg. 1993;80:1065-1067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Ozuner G, Hull T, Lee P, Fazio VW. What happens to a pelvic pouch when a fistula develops? Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:543-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Zinicola R, Wilkinson KH, Nicholls RJ. Ileal pouch-vaginal fistula treated by abdominoanal advancement of the ileal pouch. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1434-1435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Wexner SD, Rothenberger DA, Jensen L, Goldberg SM, Balcos EG, Belliveau P, Bennett BH, Buls JG, Cohen JM, Kennedy HL. Ileal pouch vaginal fistulas: incidence, etiology, and management. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:460-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 119. | Tulchinsky H, Cohen CR, Nicholls RJ. Salvage surgery after restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg. 2003;90:909-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 120. | Cohen Z, Smith D, McLeod R. Reconstructive surgery for pelvic pouches. World J Surg. 1998;22:342-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Gaertner WB, Witt J, Madoff RD, Mellgren A, Finne CO, Spencer MP. Ileal pouch fistulas after restorative proctocolectomy: management and outcomes. : Poster presentation at the Annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, Phoenix, Arizona 2013; . |

| 122. | Rosser C. The relation of fistula-in-ano to cancer of the anal canal. Am Proct Soc. 1934;35:65-71. |

| 123. | Korelitz BI. Carcinoma arising in Crohn’s disease fistulae: another concern warranting another type of surveillance. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2337-2339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 124. | Anthony T, Simmang C, Lee EL, Turnage RH. Perianal mucinous adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 1997;64:218-221. [PubMed] |

| 125. | Erhan Y, Sakarya A, Aydede H, Demir A, Seyhan A, Atici E. A case of large mucinous adenocarcinoma arising in a long-standing fistula-in-ano. Dig Surg. 2003;20:69-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 126. | Marti L, Nussbaumer P, Breitbach T, Hollinger A. [Perianal mucinous adenocarcinoma. A further reason for histological study of anal fistula or anorectal abscess]. Chirurg. 2001;72:573-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 127. | Navarra G, Ascanelli S, Turini A, Lanza G, Gafà R, Tonini G. Mucinous adenocarcinoma in chronic anorectal fistula. Chir Ital. 1999;51:413-416. [PubMed] |

| 128. | Papapolychroniadis C, Kaimakis D, Giannoulis K, Berovalis P, Karamanlis E, Haritanti A, Leukopoulos A, Kokkonis G, Masoura OM, Dimitriadis A. A case of mucinous adenocarcinoma arising in long-standing multiple perianal and presacral fistulas. Tech Coloproctol. 2004;8 Suppl 1:s138-s140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 129. | Patrinou V, Petrochilos J, Batistatou A, Oneniadum A, Venetsanou-Petrochilou C. Mucinous adenocarcinoma arising in chronic perianal fistulas. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:175-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 130. | Schaffzin DM, Stahl TJ, Smith LE. Perianal mucinous adenocarcinoma: unusual case presentations and review of the literature. Am Surg. 2003;69:166-169. [PubMed] |

| 131. | Gaertner WB, Hagerman GF, Finne CO, Alavi K, Jessurun J, Rothenberger DA, Madoff RD. Fistula-associated anal adenocarcinoma: good results with aggressive therapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1061-1067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 132. | Spencer JA, Ward J, Beckingham IJ, Adams C, Ambrose NS. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging of perianal fistulas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:735-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 133. | Lee SH, Zucker M, Sato T. Primary adenocarcinoma of an anal gland with secondary perianal fistulas. Hum Pathol. 1981;12:1034-1037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 134. | Getz SB, Ough YD, Patterson RB, Kovalcik PJ. Mucinous adenocarcinoma developing in chronic anal fistula: report of two cases and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:562-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 135. | Tarazi R, Nelson RL. Anal adenocarcinoma: a comprehensive review. Semin Surg Oncol. 1994;10:235-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 136. | Zaren HA, Delone FX, Lerner HJ. Carcinoma of the anal gland: case report and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 1983;23:250-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 137. | Basik M, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Penetrante R, Petrelli NJ. Prognosis and recurrence patterns of anal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 1995;169:233-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 138. | Nelson RL, Prasad ML, Abcarian H. Anal carcinoma presenting as a perirectal abscess or fistula. Arch Surg. 1985;120:632-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 139. | Cohen JL, Stricker JW, Schoetz DJ, Coller JA, Veidenheimer MC. Rectovaginal fistula in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:825-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 140. | Yamamoto T, Bain IM, Allan RN, Keighley MR. Persistent perineal sinus after proctocolectomy for Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:96-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |