Revised: November 30, 2013

Accepted: January 13, 2014

Published online: February 26, 2014

Processing time: 239 Days and 1.8 Hours

Cardiac metastases are among the topics with limited systematic reviews. Theoretically, the heart can be infiltrated by any malignancy with the ability to spread to distant structures. Thus far, no specific tumors are known to have a predilection for the heart, but some do metastasize more often than others, for example, melanoma and primary mediastinal tumors. We report a case of cardiac metastasis from a diffuse large B cell lymphoma in a young man. The peculiarity of this case is that besides the involvement of right ventricle and atrium, the tricuspid valve was also infiltrated. Valvular metastasis is rarely reported in the medical literature.

Core tip: This manuscript describes a case of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma involving the heart, in particular affecting the tricuspid valve. The clinical features in this case are clearly illustrated. The peculiarity of this case report is that besides the involvement of the right ventricle and atrium, the tricuspid valve was also infiltrated. Secondary valvular metastasis is unusual and the patient remained in remission after a course of chemotherapy.

- Citation: Abdullah HN, Nowalid WKWM. Infiltrative cardiac lymphoma with tricuspid valve involvement in a young man. World J Cardiol 2014; 6(2): 77-80

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v6/i2/77.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v6.i2.77

Primary cardiac tumors are extremely uncommon, with a reported prevalence of 0.001% to 0.28%[1]. On the other hand, the incidence of secondary cardiac tumors is not as low as expected, ranging from 2% to 18.3%[2]. There is growing awareness of the pathological and clinical effects of cardiac metastasis. Although metastatic heart tumors occur comparatively more frequently than primary tumors of the heart, they rarely gain clinical attention. Antemortem diagnosis of cardiac metastasis is seldom made because more than 90% are clinically silent[1]. Besides, the signs of cardiac involvement may be overlooked when the tumors are advanced with widespread involvement of other organs. The clinical manifestations may be due to the valvular involvement or diminished cardiac function, which can be similar to a primary cardiac tumor, although intramural growth of secondary cardiac tumors is unusual. In addition, cardiac rhythm disturbances, conduction defects, syncope, distant embolism and pericardial effusion can occur. Not uncommonly, cardiac infiltration contributes to the mechanism of death in the affected person. The ability to metastasize to the heart depends on several factors, including the biological characteristics and histological subtype of the primary neoplasm, as well as the functional status of the cardiovascular system[2,3]. Myocardial contractility may have a dual effect of both hindering and promoting the formation of cardiac metastasis; good contraction hinders the spreading of intramural tumor metastasis by facilitating lymph and blood drainage and therefore displacing any cardiac tumor-produced emboli, but on the other hand it helps neoplastic cells diffuse along the epicardial surface. Poor myocardial contractility would therefore create an opposite mechanism[2].

A 46-year-old man was admitted with symptomatic decompensated heart failure. He complained of progressive bilateral pitting edema with dyspnea on exertion and reduced effort tolerance of 3 wk duration. However, he denied orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. He had anorexia and weight loss for the past 3 mo. He had a 5 year history of hypertension which was well-controlled with oral antihypertensives. He had multiple admissions for angina but the coronary angiogram showed no stenosis. His previous echocardiography examination was normal. He was not a smoker. There was no family history of hematogenous malignancy or exposure to radiation at a young age.

He was thin with obvious muscle wasting. His conjunctiva was pink and there was no jaundice. The jugular venous pressure was elevated and he had gross leg edema. There was multiple small shotty cervical lymphadenopathy as well as several others in the axillary and inguinal region. The apex beat was displaced but the heart sounds were normal. There was no sign of cardiac tamponade. The chest examination was insignificant. There was no hepatosplenomegaly and ascites.

The hemoglobin level was 125 g/L. The total white cell count was 8.7 × 109/L and the platelet count was 360 × 109/L. The liver function test was normal with serum albumin of 47.1 g/L and serum globulin of 35.7 g/L. Serum transaminases were normal. The renal profile was impaired with calculated GFR of 27.5 mL/min per 1.73 m2. Serum lactate dehydrogenase was 268 U/L. Other hematology parameters were within normal range.

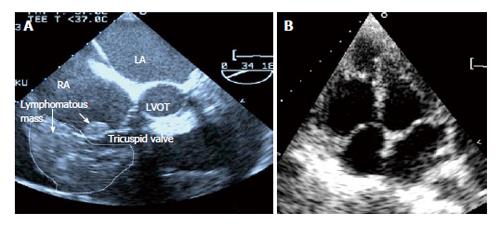

The transthoracic echocardiogram showed global pericardial effusion measuring 1.2-1.8 cm. The left ventricular function was 63% with mild tricuspid incompetence. An incidental finding of a right atrium and right ventricular mass was also made. An infiltrating tumor was also seen on the annulus of the anterior tricuspid valve and endocardium. The right ventricle was dilated with poor function. The right ventricle and atrium was not collapsing in systole to suggest cardiac tamponade. A repeat transesophageal echocardiography confirmed the diagnosis (Figure 1A).

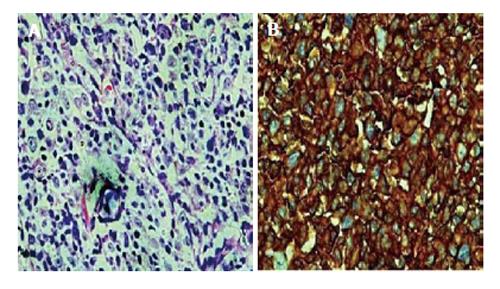

Biopsy of the left axillary lymph node was performed and the histopathological examination showed diffuse malignant, large lymphoid cells consisting of centroblasts, immunoblasts and large centrocyte-like cells with occasional multinucleated cells. The large lymphoid cells were positive for CD20, weakly positive for Bcl-2 and negative for T-cell markers CD3 and CD5, and CD10. The diagnosis was diffuse large B-cell Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Figure 2). Computed tomography of the neck, thorax and abdomen showed multiple supra and infra-diaphragmatic enlarged lymph nodes which were suggestive of lymphoma.

The patient underwent 7 cycles of monthly chemotherapy consisting of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and prednisolone (R-CHOP). He acquired clinical remission after the chemotherapy and has remained well for the past 4 years. Clinically, there was resolution of the multiple lymphadenopathies and a repeat transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography showed complete resolution of the tumor bulk with disappearance of the tumor infiltration on the tricuspid valve leaflet (Figure 1B). A fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (CT/FDG-PET) scan done 6 mo after the completion of chemotherapy showed no evidence of active lymphoma. The patient has remained in good health 4 years after the diagnosis and currently still under our follow up.

Cardiac metastases refer to distant spread of tumor to any structures of the cardiovascular system, including the pericardium, epicardium, myocardium, endocardium, great vessels and coronary arteries, as well as tumors affecting the heart cavities or producing intramural neoplastic thrombi. Cardiac metastases are commoner than a primary tumor of the heart. The incidence from autopsy study varies between 2% and 18.3%[1]. Common primary tumors are bronchus and breast cancers, although lymphomas, leukemia and malignant melanoma may sometimes give rise to cardiac metastasis[4]. In a recent study from Italy by Bussani et al[2], the tumors that commonly metastasize to the heart are pleural mesothelioma (48.4%), melanoma (27.8%), lung adenocarcinoma (21%), undifferentiated carcinoma (19.5%), lung squamous cell carcinoma (18.2%), breast carcinoma (15.5%), ovarian carcinoma (10.3%), lymphoproliferative neoplasm (9.4%), bronchoalveolar carcinomas (9.8%), gastric carcinoma (8%), renal carcinomas (7.3%) and pancreatic carcinoma (6.4%)[2]. The prevalence was somewhat different from an earlier study[4].

Tumors can spread to the heart via four mechanisms, including direct tumor extension, hematogenous spread, retrograde lymphatic system dissemination and intracavitary diffusion via either the inferior vena cava or pulmonary vein. The different mechanisms result in specific involvement of the structure in the heart. In our patient, we postulated that the initial metastases involved the myocardium via one of the mechanisms above and later spread to the pericardium, resulting in moderate pericardial effusion.

Cardiac involvement in lymphoma is rare but in a recent autopsy study of malignant lymphoma, cardiac metastasis was found in 16% of the cases[3]. Neoplastic infiltration by lymphoma typically tends to replace the myocardial tissue. Large areas of the heart are replaced by homogenous grayish white tissue with the typical “fish-meat” appearance. Despite the massive involvement of the myocardial contractile tissue, cardiac symptoms may be absent or non-specific. In the few existing cases in the medical literature, the heart seems to be more often involved in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, whereas the pericardium is more often metastasized by Hodgkin’s lymphoma[5].

Clinical presentations of cardiac metastasis by lymphoma are extremely variable. They are determined by the location, size, growth rate, degree of invasiveness and friability of the neoplasm. The tumor can block the blood flow or valvular structures, leading to cardiac and valvular dysfunction. The involvement of the tricuspid valve in our patient did not give rise to severe tricuspid regurgitation and the right ventricle metastasis rather contributed to the right heart failure. Invasion of the electrical pathways can cause arrhythmias and pericardial seeding may lead to malignant pericardial effusion or tamponade. The tumor may also cause distant embolization. In addition, sudden death may occur as a result of myocardial rupture, ventricular arrhythmias or acute myocardial infarction. Constitutional symptoms include fever, weight loss, palpitations, dyspnea and poor appetite. Lymphomatous infiltration of the heart may remain clinically silent and is often not detected until death occur[6].

Lymphomatous cardiac metastases are usually small and multiple, although a single large tumor mass is also observed. Focal or diffuse tumor infiltrations of the pericardium, myocardium or endocardium have been observed in lymphoma as well. In contrary to leukemic infiltration, lymphoma depositions are usually grossly discernible. The right side of the heart has been found to be more frequently involved than the left heart. This was apparent in our patient where the tumor mass was located in the right atrium and at the atrioventricular junction. Heart valves are unusual targets for tumor metastases and thus tricuspid valve involvement, as seen in our patient, is uncommon. Thus far, there is only one reported case of valvular involvement due to “neoplastic” thrombotic endocarditis by Bussani et al[7]. In our patient, the tricuspid valve involvement is most likely due to direct tumor metastasis as it completely resolved with chemotherapy, without the need for anticoagulation. Although one may argue that the valvular lesion could be due to vegetation and thrombus, they are often associated with other complications such as atrial fibrillation, ventricular aneurysm, cardiomyopathy or infective endocarditis. In the absence of these complications in our patient, the possibility of thrombosis and vegetation is less likely.

A multimodality imaging may be used to diagnose a cardiac metastasis. A plain chest radiograph lacks sensitivity and specificity as an initial diagnostic tool. Transthoracic echocardiography may be the first non-invasive screening tool but the restricted acoustic window remains a significant limitation, making transesophageal echocardiography a more sensitive technique. Computed tomography adequately demonstrates morphology, location and extent of a cardiac neoplasm with a larger view, while magnetic resonance signal intensity with contrast enhancement results in superior images identifying anatomy, blood flow, cardiac function and tissue characterization of the mass. CT/ FDG-PET scan has recently been reported to be useful in monitoring the disease response to chemotherapy[8,9].

Treatment options are usually aggressive chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy but the results are usually dismal. This may be due to late diagnosis or the aggressiveness of the tumor. Thus far, there is no evidence that surgical resection improves survival and furthermore it is often difficult to resect such tumors. The commonest type is B-cell lymphoma which usually responds well to chemotherapy. Chemotherapy regimens such as R-CHOP have been shown to be effective and prolong survival in the few reported cases[10]. Without therapy, the median survival of patients is often less than 6 mo, while patients treated with chemotherapy or radiation have median survival of about 1 year. Our patient underwent 7 cycles of chemotherapy with the R-CHOP regime. The patient remained in clinical remission when he was last seen in the clinic recently.

In conclusion, cardiac involvement in lymphomatous infiltration is rare but early diagnosis is crucial in improving the prognosis. The institution of effective chemotherapy may cure the disease, avert invasive debulking surgery and maintain long term clinical remission.

A 46-year-old man was admitted with symptomatic decompensated heart failure.

The peculiarity of this case is that besides the involvement of right ventricle and atrium, the tricuspid valve was also infiltrated.

The transthoracic echocardiogram showed global pericardial effusion measuring 1.2-1.8 cm.

The patient underwent 7 cycles of monthly chemotherapy consisting of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin and prednisolone (R-CHOP).

Chemotherapy regimens such as R-CHOP have been shown to be effective and prolong survival in the few reported cases.

The institution of effective chemotherapy may cure the disease, avert invasive debulking surgery and maintain long term clinical remission.

The manuscript describes a case of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma involving the heart, in particular affecting the tricuspid valve. Clinical features were clearly illustrated.

P- Reviewers: Lo AWI, Vermeersch P S- Editor: Zhai HH L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Al-Mamgani A, Baartman L, Baaijens M, de Pree I, Incrocci L, Levendag PC. Cardiac metastases. Int J Clin Oncol. 2008;13:369-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bussani R, De-Giorgio F, Abbate A, Silvestri F. Cardiac metastases. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:27-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 370] [Cited by in RCA: 469] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chinen K, Izumo T. Cardiac involvement by malignant lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of 25 autopsy cases based on the WHO classification. Ann Hematol. 2005;84:498-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | BISEL HF, Wroblewski F, Ladue JS. Incidence and clinical manifestations of cardiac metastases. J Am Med Assoc. 1953;153:712-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Moore JA, DeRan BP, Minor R, Arthur J, Fraker TD. Transesophageal echocardiographic evaluation of intracardiac lymphoma. Am Heart J. 1992;124:514-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cho JG, Ahn YK, Cho SH, Lee JJ, Chung IJ, Park MR, Kim HJ, Jeong MH, Park JC, Kang JC. A case of secondary myocardial lymphoma presenting with ventricular tachycardia. J Korean Med Sci. 2002;17:549-551. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Bussani R, Silvestri F. Neoplastic thrombotic endocarditis of the tricuspid valve in a patient with carcinoma of the thyroid. Report of a case. Pathol Res Pract. 1999;195:121-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mato AR, Morgans AK, Roullet MR, Bagg A, Glatstein E, Litt HI, Downs LH, Chong EA, Olson ER, Andreadis C. Primary cardiac lymphoma: utility of multimodality imaging in diagnosis and management. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:1867-1870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | O’Mahony D, Peikarz RL, Bandettini WP, Arai AE, Wilson WH, Bates SE. Cardiac involvement with lymphoma: a review of the literature. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma. 2008;8:249-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nonami A, Takenaka K, Kamezaki K, Miyamoto T, Harada N, Nagafuji K, Teshima T, Harada M. Successful treatment of primary cardiac lymphoma by rituximab-CHOP and high-dose chemotherapy with autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2007;85:264-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |