Published online May 26, 2020. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v12.i5.220

Peer-review started: March 1, 2020

First decision: April 3, 2020

Revised: April 8, 2020

Accepted: May 5, 2020

Article in press: May 5, 2020

Published online: May 26, 2020

Processing time: 84 Days and 14.5 Hours

Cardiac lipomas are rare benign tumors commonly found in the right atrium or left ventricle. Patients are usually asymptomatic, and clinical presentation depends on location and adjacent structures impairment. Right ventricle lipomas are scarce in the literature. Moreover, the previous published cases were reported in over 18-year-old patients.

We report a giant right ventricle lipoma discovered incidentally in a 17-year-old female while performing preoperative work-up. The diagnosis was confirmed by histopathological examination, and a conservative approach was performed.

Multimodal cardiac imaging and histopathological examination are required for a definitive diagnosis. The therapeutic approach depends on clinical presentation.

Core tip: We describe an extremely rare case of cardiac lipoma raising from the right ventricle in a young patient aged less than 18-years-old. It was discovered incidentally while performing preoperative workup. Variable cardiac imaging modalities such as transthoracic echocardiogram, cardiac computed tomography-scan, positron emission tomography-scan and cardiac magnetic resonance were used. Then, the diagnosis was confirmed by histopathological examination.

- Citation: Elenizi K, Matta A, Alharthi R, Campelo-Parada F, Lhermusier T, Bouisset F, Elbaz M, Carrié D, Roncalli J. Incidental discovery of right ventricular lipoma in a young female associated with ventricular hyperexcitability: An imaging multimodality approach. World J Cardiol 2020; 12(5): 220-227

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v12/i5/220.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v12.i5.220

A lipoma is a benign fat tissue tumor that can grow in most body parts. However, cardiac lipomas occur exclusively in adults[1,2]. These tumors are commonly asymptomatic and discovered incidentally while performing cardiac investigations for other disease or diagnosed on autopsies. Large size or huge lipoma may cause symptoms via mass effect on the adjacent structures such as coronary arteries provoking angina and left ventricle causing heart failure. Cardiac lipomas arising from the myocardium are more likely to induce arrhythmia by infiltrating the electrical circuit. Indeed, clinical presentation depends on location and size of cardiac lipomas. We present a right ventricular lipoma that was found incidentally during a preoperative work-up in a young patient with excessive premature ventricular contractions detected afterwards.

We report a case of giant cardiac lipoma in a 17-year-old female previously healthy while performing preoperative work-up for tonsillectomy.

A 17-year-old female with a known case of Prader-Willi syndrome since childhood was hospitalized for a preoperative tonsillectomy evaluation. She was referred for surgery due to several episodes of infective tonsillitis (> 6) in the last year. Physical exam was unremarkable for cardiopulmonary findings. The patient was asymptomatic with normal hemodynamic parameters. Laboratory studies revealed normal white blood cell count and C-reactive protein and electrolyte panel with normal renal and liver function. Electrocardiogram showed regular sinus rhythm with T waves inversion in all territories. Subsequently, Holter electrocardiogram found repetitive polymorphic ventricular contraction. Afterwards, an electrocardiogram stress test was performed with suboptimal results due to many premature ventricular contractions originating from the apex and inferior wall.

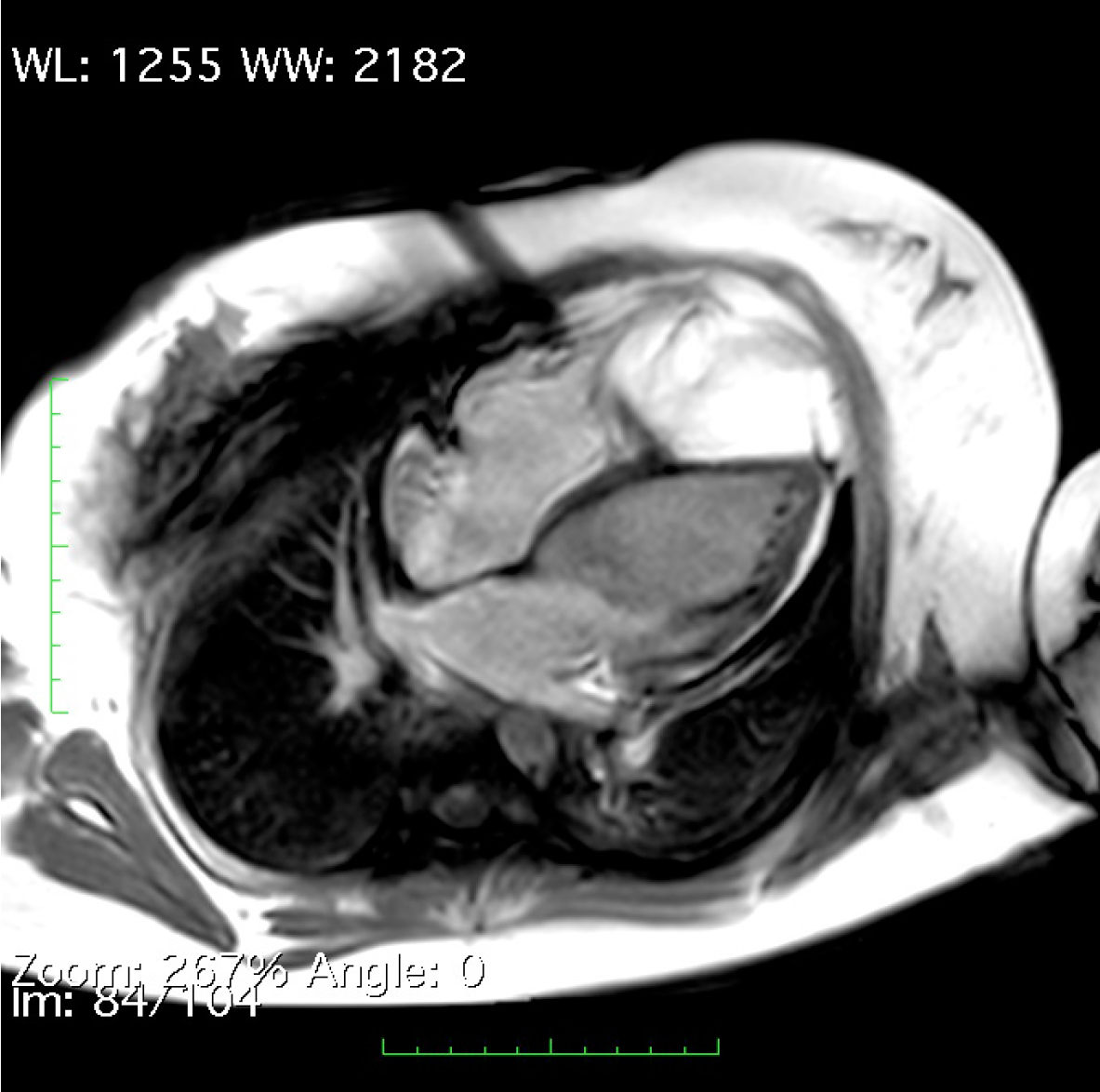

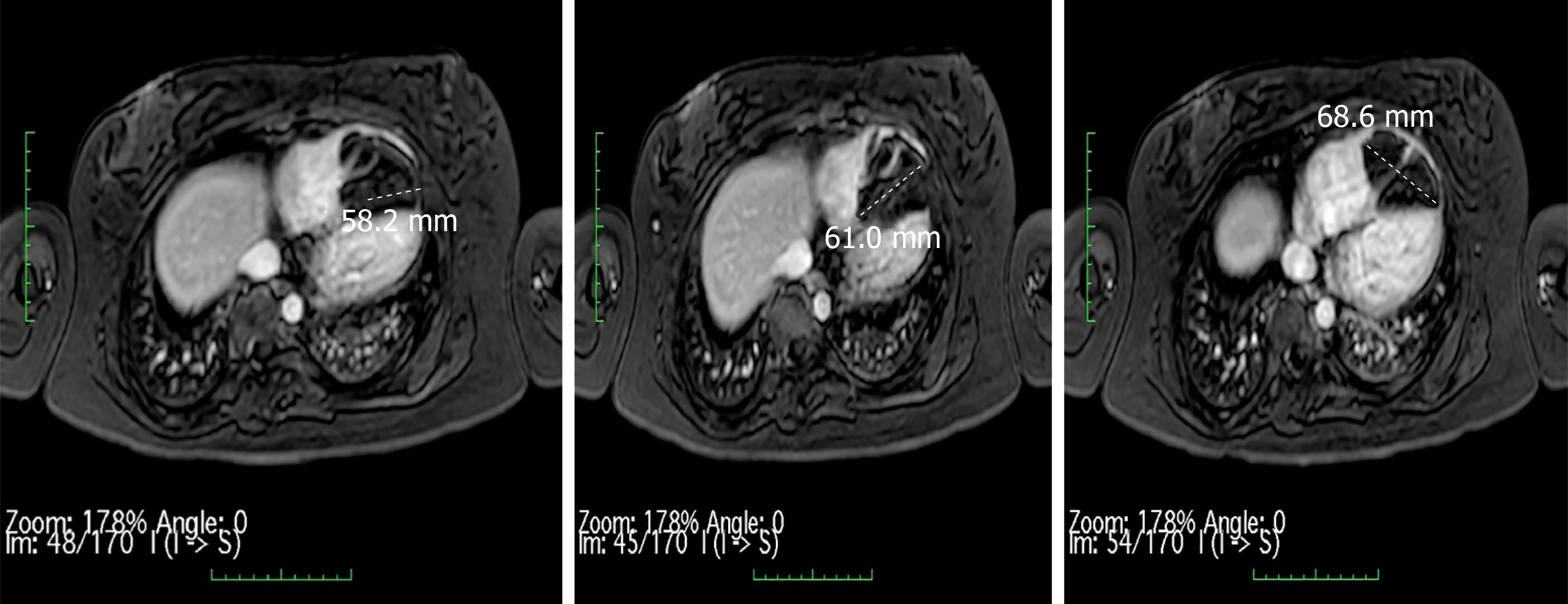

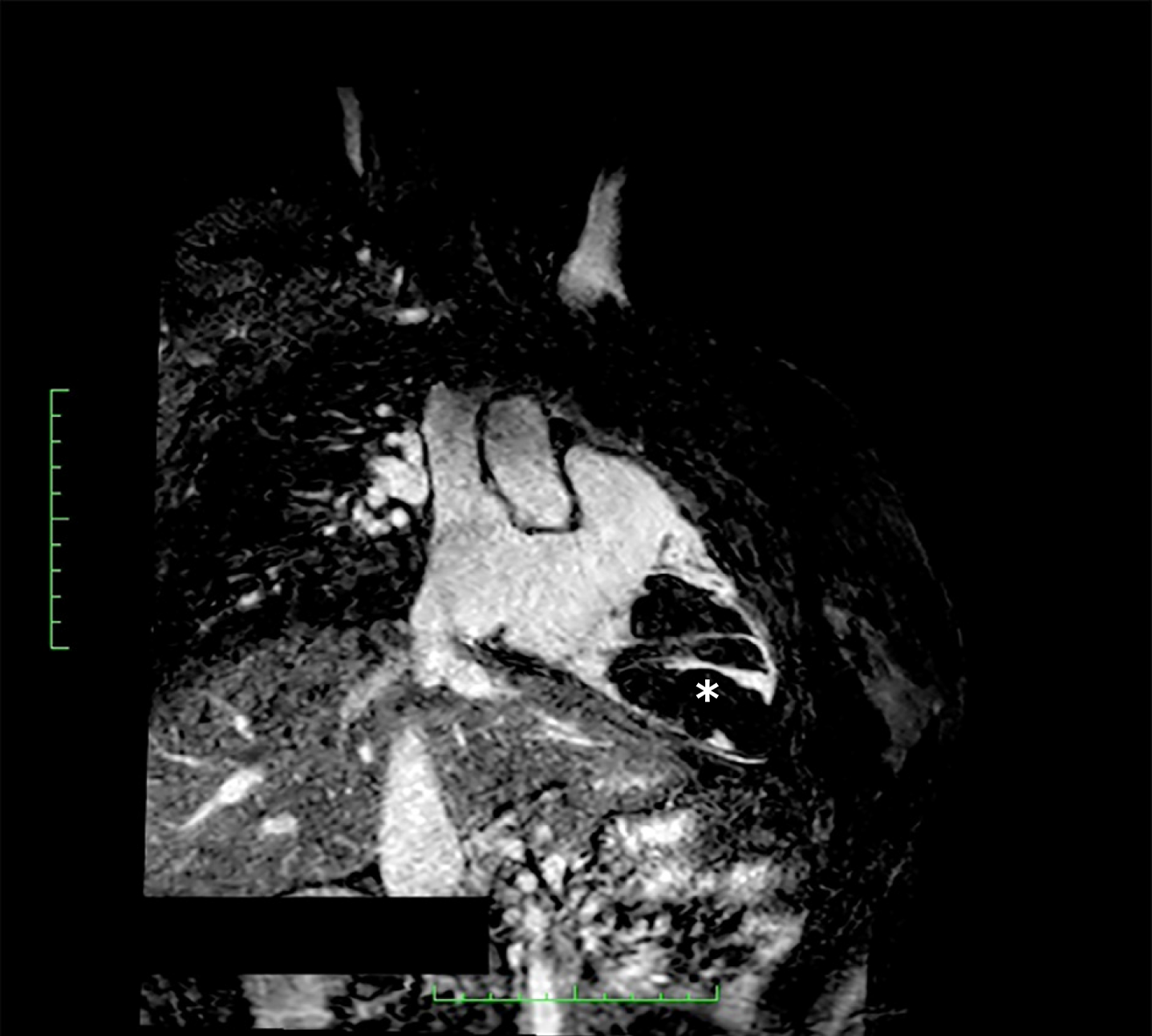

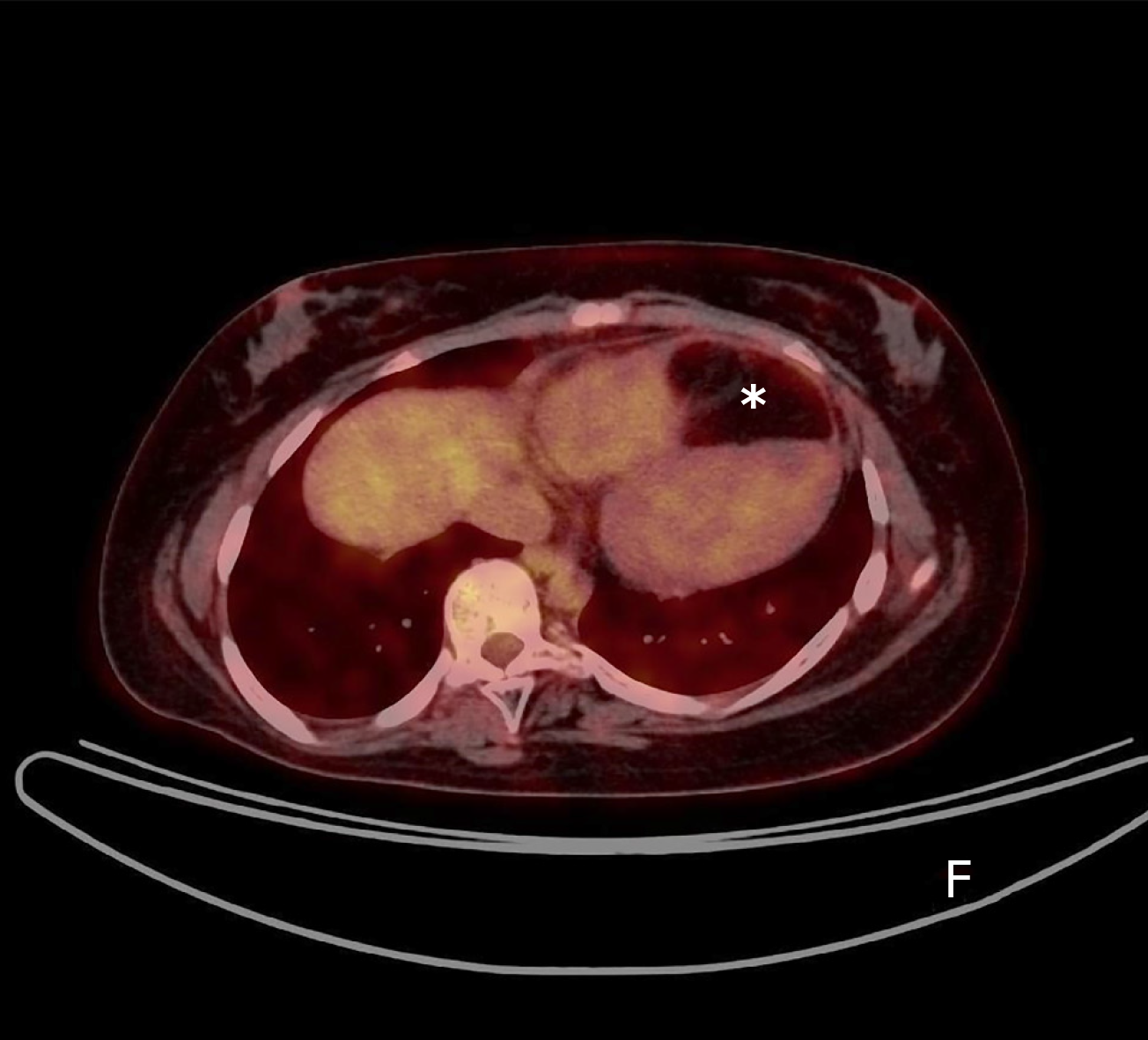

As a result, we proceeded with transthoracic echocardiogram, which revealed a giant mass located apically in the right ventricle and extended to the epicardium measuring transversally 8.4 cm on its maximal diameter (Figure 1). Computed tomography scan showed a well-circumscribed and homogenously hypodense mass obscuring the apical right ventricle (Figure 2). Searching for the etiology, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the diagnostic modality of choice, showed a right ventricular septate mass with fat signal transmission and homogenous contours that had normal gadolinium enhancement protruding to the apical epicardium without extracardiac structures involved The patient had normal biventricular function (Figures 3-7). In order to differentiate primary from secondary cardiac tumors and to search for secondary localizations, we performed a positron emission tomography scan that showed a nonfunctional mass (Figure 8).

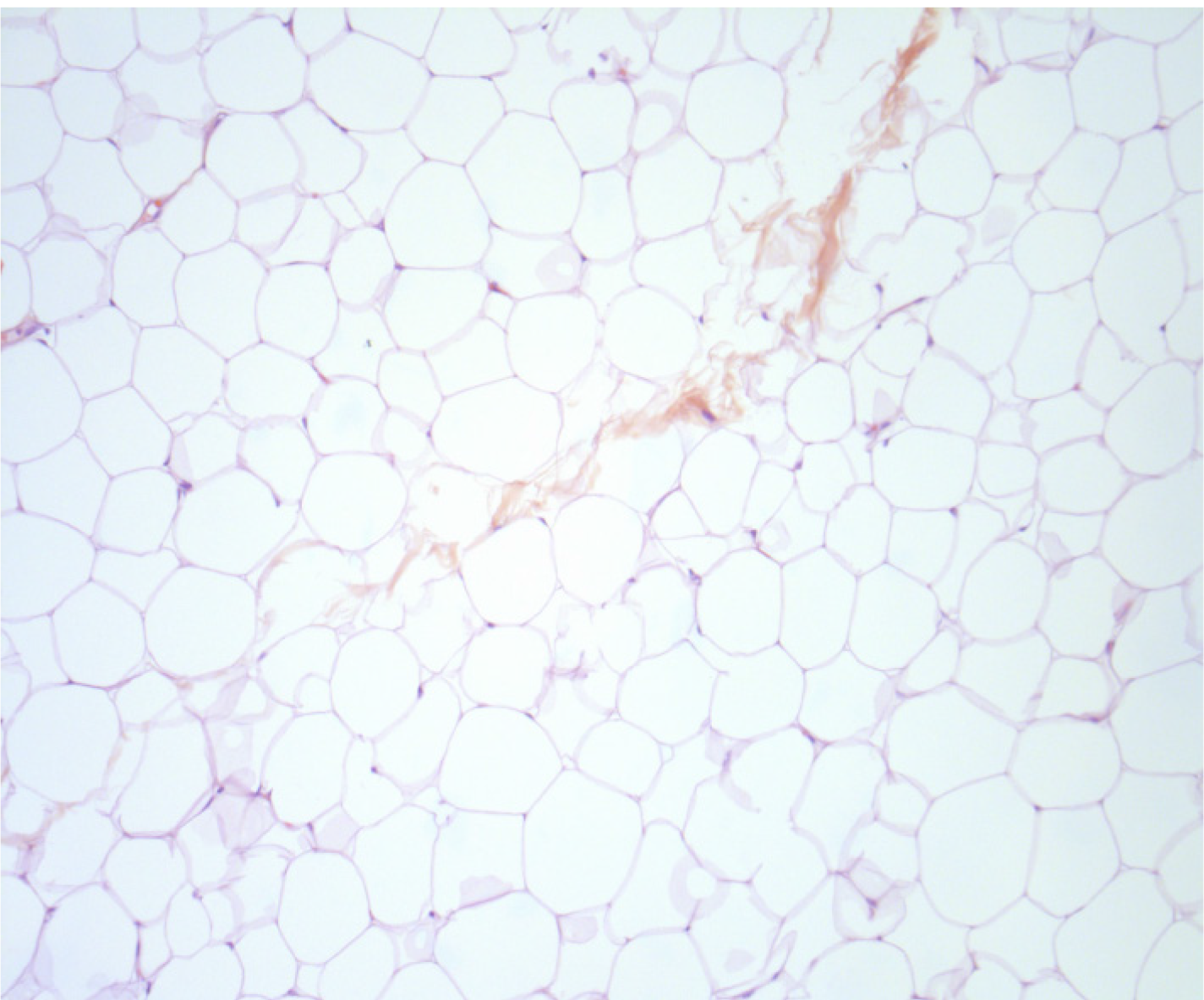

Afterwards, percutaneous myocardial biopsy was done, and histopathological examination showed adipose tissue without malignant features confirming cardiac lipoma (Figure 9).

Right ventricular lipoma.

After a multidisciplinary decision, surgical excision was avoided as the patient was asymptomatic with no hemodynamic instability or ventricular function impairment. The patient started sotalol to reduce the risk of ventricular arrhythmia in the presence of documented excessive premature ventricular contractions in view of reported ventricular arrhythmias in cardiac lipomas patients.

Patient was discharged with regular follow-up.

Cardiac lipomas are rare[3,4] and found mostly in asymptomatic patients[5,6]. A review of articles related to cardiac lipomas shows that interatrial septum is the most common position for lipomas and lipomatous hypertrophy[7]. They have a predilection for the right atrium and left ventricle but can originate in any part of the heart. However, right ventricle involvement is rare[8,9]. They also have a predilection for the pericardium, but it may originate from all three layers of cardiac tissue[10]. Symptoms depend mostly on anatomical location and mass effect to adjacent structures causing hemodynamic compromise or conduction abnormalities, which can ultimately lead to heart failure[11].

Various imaging modalities can accurately determine localization, size and shape and most importantly differentiate lipomas from liposarcomas.

Transthoracic echocardiogram is usually the first exam to be done due to high accessibility with a high safety profile. Intracavitary cardiac lipomas are usually hyperechogenic while pericardial lipomas are hypoechogenic[12]. It is not known if this variability in echogenicity is related to the position of the lipoma. In our case it is isoechogenic. Heterogenic and large size lipomas are suspicious for liposarcomas.

On computed tomography scans, lipomas typically appear as well-circumscribed and homogenously hypodense masses, which was seen in our patient. Calcifications raise the suspicion for liposarcomas[13], but differentiation with certainty between them is only assured by histopathology.

MRI is very utile in delineating contours and distinguishing characteristics with specificity reaching as high as 100%. In addition, MRI is helpful in discriminating any atypical features and in better visualizing adjacent structure invasion. Malignant features include the presence of septa > 2 mm, intralesional nodules and the inhomogeneity of the signal.

Lipomas usually have a homogenous signal with high signal intensity appearing white on T1-weighted sequence and a low signal intensity appearing dark on T2-weighted sequence. An important sequence for diagnosing lipomas is named pre- and post-fat-saturated T1-weighted Fast spin-echo sequences, which shows signal dropout on fat saturation sequence confirming the diagnosis of a fat-containing mass. It is worth mentioning that cardiac lipomas do not show delayed gadolinium enhancement. THRIVE protocol is an optimized fast T1 weighted 3-dimensional imaging technique combining sensitivity encoding, large volume coverage and uniform fat suppression for better quantification. Another incredible tool for achieving rapid and high signal-to-noise ratio imaging is balanced turbo field-echo steady-state free precession MR technique, which has been applied successfully to cardiac MRI[14].

The role of positron emission tomography scans is to differentiate benign cardiac tumors from malignant primary tumors or metastasis with high sensitivity[15]. It evaluates functional characteristics of soft tissue masses. Lipomas have consistently low fluorodeoxyglucose as they are hypodense and hypometabolic as demonstrated in our case. However, it is important to emphasize that lipomatous hypertrophy of the septum may be metabolically active on positron emission tomography scan as it contains brown fat. Lastly, myocardial biopsy with histopathological examination remains the definitive diagnostic method showing in our case the adipose tissue with no suspect elements of malignancy.

Benign cardiac lipomas are associated with a good long-term prognosis, and furthermore a good outcome is observed in 95% of patients after surgical excision. As cardiac lipomas are rare, no guidelines have been established to define surgical intervention indications. However, there is a consensus that surgical resection needs to be considered in symptomatic patients. The data concerning prognosis of patients treated conservatively are lacking due to the rarity of cardiac lipomas. Our patient is followed regularly with no documented abnormal clinical signs or appearance of warning symptoms necessitating surgical intervention at the present time.

Multiple imaging modalities and histopathological exam are the mainstay for confirming the diagnosis of cardiac lipomas. In most patients, surgical intervention is limited for cases with associated symptoms, life-threating arrhythmias and flow obstruction leading to congestive heart failure or myocardial ischemia. As evidence is still lacking for cardiac lipomas, decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country/Territory of origin: France

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kirnap M, Xie H S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Liu MY

| 1. | Ashar K, van Hoeven KH. Fatal lipoma of the heart. Am J Cardiovasc Pathol. 1992;4:85-90. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Roberts WC. Primary and secondary neoplasms of the heart. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:671-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wu S, Teng P, Zhou Y, Ni Y. A rare case report of giant epicardial lipoma compressing the right atrium with septal enhancement. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;10:150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Singh S, Singh M, Kovacs D, Benatar D, Khosla S, Singh H. A rare case of a intracardiac lipoma. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;9:105-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang H, Hu J, Sun X, Wang P, Du Z. An asymptomatic right atrial intramyocardial lipoma: a management dilemma. World J Surg Oncol. 2015;13:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Steger CM. Intrapericardial giant lipoma displacing the heart. ISRN Cardiol. 2011;2011:243637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fang L, He L, Chen Y, Xie M, Wang J. Infiltrating Lipoma of the Right Ventricle Involving the Interventricular Septum and Tricuspid Valve: Report of a Rare Case and Literature Review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e2561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rajiah P, To AC, Tan CD, Schoenhagen P. Multimodality imaging of an unusual case of right ventricular lipoma. Circulation. 2011;124:1897-1898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Grande AM, Minzioni G, Pederzolli C, Rinaldi M, Pederzolli N, Arbustini E, Viganò M. Cardiac lipomas. Description of 3 cases. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 1998;39:813-815. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Puvaneswary M, Edwards JR, Bastian BC, Khatri SK. Pericardial lipoma: ultrasound, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Australas Radiol. 2000;44:321-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Verberkmoes NJ, Kats S, Tan-Go I, Schönberger JP. Resection of a lipomatous hypertrophic interatrial septum involving the right ventricle. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2007;6:654-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ragland MM, Tak T. The role of echocardiography in diagnosing space-occupying lesions of the heart. Clin Med Res. 2006;4:22-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kassop D, Donovan MS, Cheezum MK, Nguyen BT, Gambill NB, Blankstein R, Villines TC. Cardiac Masses on Cardiac CT: A Review. Curr Cardiovasc Imaging Rep. 2014;7:9281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Plein S, Bloomer TN, Ridgway JP, Jones TR, Bainbridge GJ, Sivananthan MU. Steady-state free precession magnetic resonance imaging of the heart: comparison with segmented k-space gradient-echo imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;14:230-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rahbar K, Seifarth H, Schäfers M, Stegger L, Hoffmeier A, Spieker T, Tiemann K, Maintz D, Scheld HH, Schober O, Weckesser M. Differentiation of malignant and benign cardiac tumors using 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:856-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |