Published online Oct 26, 2019. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v11.i10.244

Peer-review started: June 6, 2019

First decision: July 30, 2019

Revised: August 29, 2015

Accepted: September 13, 2019

Article in press: September 13, 2019

Published online: October 26, 2019

Processing time: 242 Days and 7.5 Hours

Mortality and cause of death data are fundamental to health policy development. Civil Registration and Vital Statistics systems are the ideal data source, but the system is still under development in Indonesia. A national Sample Registration System (SRS) has provided nationally representative mortality data from 128 sub-districts since 2014. Verbal autopsy (VA) is used in the SRS to obtain causes of death. The quality of VA data must be evaluated as part of the SRS data quality assessment.

To assess the strength of evidence used in the assignment of Ischaemic Heart Disease (IHD) as causes of death from VA.

The sample frame for this study is the 4,070 deaths that had IHD assigned as the underlying cause in the SRS 2016 database. From these, 400 cases were randomly selected. A data extraction form and data entry template were designed to collect relevant data about IHD from VA questionnaires. A standardised categorisation was designed to assess the strength of evidence used to infer IHD as a cause of death. A pilot test of 50 cases was carried out. IBM SPSS software was used in this study.

Strong evidence of IHD as a cause of death was assigned based on surgery for coronary heart disease, chest pain and two out of: sudden death, history of heart disease, medical diagnosis of heart disease, or terminal shortness of breath. More than half (53%) of the questionnaires contained strong evidence. For deaths outside health facilities, VA questionnaires for male deaths contained acceptable evidence in significantly higher proportions as compared to those for female deaths. (P < 0.001). Nearly half of all IHD deaths were concentrated in the 50-69 year age group (48.40%), and a further 36.10% were aged 70 years or more. Nearly two-thirds of the deceased were male (58.40%). Smoking behaviour was found in 44.11% of IHD deaths, but this figure was 73.82% among males.

More than half of the VA questionnaires from the study sample were found to contain strong evidence to infer IHD as the cause of death. Results from medical records such as electrocardiograms, coronary angiographies, and load tests could have improved the strength of evidence and contributed to IHD cause of death diagnosis.

Core tip: In many countries in Southeast Asia, systems for recording mortality and causes of death are under development. In such settings, due to large proportions of deaths happening outside of health facilities, verbal autopsy interviews with families of the deceased are often used to ascertain the cause of death. However, there is a need to evaluate the quality of cause of death estimation from the verbal autopsy. This study specifically addresses the assignment of ischemic heart disease as a cause of death, concluding that a significant proportion of deaths were assigned this cause using strong evidence.

- Citation: Zhang W, Usman Y, Iriawan RW, Lusiana M, Sha S, Kelly M, Rao C. Evaluating the quality of evidence for diagnosing ischemic heart disease from verbal autopsy in Indonesia. World J Cardiol 2019; 11(10): 244-255

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v11/i10/244.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v11.i10.244

Sustained, accurate and timely data on mortality and cause of death patterns, especially the leading causes of death, is essential for local, national and global public health policy development, evaluation, and research[1,2]. The optimal method of obtaining data on mortality and causes of death is to have an attending physician complete a medical certificate of cause of death with the support of detailed clinical documents and to register these deaths in a universal Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) system[3,4]. Efficient CRVS systems are still under development in many countries in the Asia-Pacific region, including Indonesia. As an interim step towards strengthening CRVS systems, Indonesia has established a national Sample Registration System (SRS)[5], similar to other countries in the region with large populations, such as India, China, and Bangladesh[6-8]. The aim of the Indonesian national SRS is to register deaths in a nationally representative sample of 128 sub-districts across the country and to estimate indicators of total and cause-specific mortality for health policy and program evaluation. Despite potential limitations in data availability, as well as quality since its inception in 2014, the Indonesian SRS has consistently reported ischemic heart disease (IHD) among the observed leading causes of death in the sample population from 2014-2016[9]. Therefore, it is important to evaluate the reliability of the Indonesian SRS in determining IHD as an underlying cause of death.

Since most deaths in Indonesia occur at home without medical attention, there is limited potential to implement medical certification of cause of death in the SRS. Under these circumstances, an alternative process termed verbal autopsy (VA) is used to ascertain the cause of death in the Indonesian SRS. VA involves a retrospective interview with the deceased’s relatives or primary caregivers, who are familiar with the illness and circumstances preceding death[10]. The interview is carried out by trained interviewers after a certain interval following the death. The questionnaire collects information about pre-existing disease suffered by the deceased, symptoms and clinical events during the illness preceding death, as well as details of interactions with health facilities before death, as reported by the respondent. Based on the answers from the interview, the cause of death is inferred through physician review of completed questionnaires, who then assign probable cause(s) for each death, or the cause of death is inferred using computerised algorithms[10]. The World Health Organi-zation (WHO) has recognised VA as a viable alternative for ascertaining causes of death for population health assessments, where medical certification of cause of death by attending physicians is not available, and has recommended international standards for this methodology[11]. As in Indonesia, there is now a movement in other settings with low-performing vital statistics systems to integrate VA into routine data collection[12].

The diagnoses from VA can be influenced by many factors, such as the design of questionnaires, interviewer skills, characteristics of respondents (including proximity to the deceased), recall period for the interview, and method used for ascertaining causes of death[13]. Given these potential sources of bias, the WHO has recommended the conduct of scientific studies to assess the quality of causes of death from VA[14,15]. Hence, this study was designed to evaluate the quality of evidence used to assign IHD as a cause of death from VA, in order to determine the reliability of IHD mortality estimates from the Indonesian SRS. The study also evaluated potential differences in the quality of evidence according to age group, gender, and place of death of the deceased, in order to develop recommendations to strengthen VA data quality from ongoing SRS operations.

In general, the optimal method to validate VA methods is to compare the underlying cause of death derived from the VA to the reference diagnosis of the underlying cause for the same death, as derived from a pathological autopsy or the next best alternative, medical records for the deceased[16,17]. In view of the limited availability of pathological autopsies or medical records for community deaths in Indonesia, this study was designed to evaluate the quality of evidence that was available from VA questionnaires, to formulate the diagnosis of ischaemic heart disease as the underlying cause of death from VA. For this purpose, the study reviewed a sample of VA questionnaires for content related to IHD, in terms of medical history, symptoms, and signs of terminal illness, and details of clinical events and treatment as recorded in the questionnaire. VA data quality was analysed according to three categories of strong, acceptable, and weak evidence, a methodology that is conceptually similar to that used in studies to evaluate the quality of evidence for medical certification of causes of death[18-20].

A cross-sectional study was designed to evaluate the quality of evidence recorded in a sample of VA questionnaires for which IHD was diagnosed as the underlying cause of death from the SRS in 2016. Overall, 30,633 deaths were registered in the 2016 SRS, of which 4,070 deaths had IHD assigned as the underlying cause of death, and this group forms the sampling frame for this study[9]. There was no prior information on the expected proportion of VA cases with strong evidence to support an IHD diagnosis. Hence, to maximise our sample size, we hypothesised that about 50% of VA questionnaires would have strong evidence, and it was estimated that a random sample of 384 questionnaires would be required to estimate this proportion at the 95% confidence level, within a 5% tolerable margin of error[21].

A total of 400 VA questionnaires with IHD as the underlying cause of death were randomly selected from the sampling frame. At first, the sample was tested and found to be representative of the whole sampling frame by age and sex. A data extraction form was used to collect required information of interest from the sampled VA questionnaires for the variables listed in Table 1. A brief explanation of the relevance of these variables for evaluating quality of evidence from VA will help place this study into context. In general, the variables presented in Table 1 were either used to assess the quality of evidence or to analyse the determinants or predictors of data quality. The place of death, whether at home or in the hospital, could influence the availability of specific information on the terminal illness, specifically with regard to the details of treatment and diagnosis. The relationship of the respondent could determine their proximity to the deceased, and therefore their knowledge of the terminal illness and events. The length of the recall period between the death and the interview could also affect the quality of information. The past medical history and specific details of symptoms, signs and events during the terminal illness serve as primary data for reviewing physicians to formulate diagnoses.

| Data category | Data variables |

| General information of deceased | Age / sex |

| Place of death (health facilities/home) | |

| Relationship with respondent | |

| Recall period of interview | |

| Structured questions | Previous medical history (heart disease, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, etc.) |

| Signs and symptoms of terminal illness | |

| Risk factors | |

| Use of health services | |

| Cause of death provided by health staff | |

| Open sections | Respondent’s free-flowing narrative of the course of illness and terminal events |

| Information from available health records | |

| Physician reviewer’s case summary |

The questionnaires also provide important information from three sections that record information in unstructured formats. Firstly, respondents describe their recollec-tions of the symptoms and clinical events during the terminal illness leading to death, in their own words. This section is referred to as the open narrative section. Secondly, the questionnaire also records information on the use of health services and any supporting information from other health records, such as hospital discharge state-ments, laboratory or imaging test reports, or drug prescriptions, among others. Finally, the questionnaire has a section in which the reviewing physician documents a summary of his impressions from the questionnaire review, which provides a basis for his/her assignment of causes of death. In some instances, this section could include information based on the reviewing physician’s prior knowledge of the deceased and the terminal illness. Information from these three sections was trans-cribed and translated by local SRS staff, which were used in ascertaining quality of evidence.

The study team identified several key symptoms and other elements of information potentially available from VA interviews that could be used to diagnose IHD. The key symptoms include chest pain, terminal shortness of breath, and sudden death. History of heart disease in the deceased is also important evidence to support the diagnosis of IHD as the cause of death. A history of hypertension is also considered as a risk factor associated with cardiovascular disease mortality. A special variable termed “medical diagnosis” was created from the data, which was rated positive if either IHD was recorded as the cause of death reported by health staff for deaths in hospitals, or if IHD was recorded as a cause by the reviewing physician in the case summary. The study team developed three categories to assess the strength of evidence for the diagnosis of IHD, based on a combination of clinical history, symptoms and diagnostic information, as available. Each case was assigned a category of strength of evidence, the criteria for which are listed in Table 2.

| Category | Criteria | Cases | Proportion |

| Strong | (1) Surgery for coronary heart disease (1%); (2) Terminal chest pain and two of: (A) Sudden death; (B) History of heart disease; (C) Medical diagnosis of heart disease3; (D) Terminal shortness of breath. | 213 | 53% |

| Medium | (1) Terminal chest pain alone; (2) Sudden death AND either: (A) History of heart disease OR; (B) Medical diagnosis of heart disease; (3) Only medical diagnosis of heart disease. | 87 | 22% |

| Weak | (1) Only history of heart disease; (2) Only symptomatic evidence (without chest pain): (A) Sudden death; (B) Hypertension; (C) Shortness of breath. | 98 | 24.5% |

| Nil | No evidence for the cause of death. | 2 | 0.5% |

| TOTAL | 400 | 100 |

Firstly, this study calculated the distribution of IHD deaths in the study sample by sex, age, place of death (inside or outside health facilities), previous medical history, and presence of risk factors. Data quality consistency between open narratives and structured questions in the questionnaire was measured as an indicator to assess the quality of the VA interview.

Next, this study calculated the frequency and proportion of cases assigned to each category of strength of evidence. Further, the distribution of the strength of evidence was evaluated by sex, age, place of death (hospital or home), the relationship of the respondent with the deceased, and whether the respondent resided with the deceased during the course of death. IBM SPSS statistical software was used in this study to calculate chi-square values and p-values to detect the statistical significance of variation in the strength of evidence by socio-demographic information, place of death and the relationship between respondents and the deceased.

The study data were also evaluated for consistency as an indicator of data quality. In general, the open narrative section is likely to include specific elements of information, such as the occurrence of chest pain, terminal shortness of breath, and previous history of heart disease or hypertension, all of which are also directly enquired by the structured questions. Consistency of such information across both the open-ended sections as well as the structured questions can reflect the quality of the interview, as well as justify the need for both sections in the questionnaire if the information is present only in one source. This study has examined this consistency by comparing information for key variables between the structured questions and open narratives in the same questionnaire.

Ethical approval for the overall SRS study has been obtained from the Indonesian Ministry of Health. The study proposed here also obtained ethical approval from both the Australia National University Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol number 2018/493) and the Ethics Board of NIHRD, Indonesia.

As mentioned in the Methods, the study sample was tested and found to be representative of the overall IHD deaths in the SRS 2016 data. Table 3 demonstrates that more than half of the deaths were among males (58.40%), and nearly half of all IHD deaths were concentrated in the 50-69 year age-group (48.40%), in approximately the same gender ratio, and a further 36.10% were aged 70 years or more. More than twice the number of deaths occurred at home than in a health facility, while male deaths were more likely to have occurred in health facilities than female deaths, which could have an influence on gender diffe-rentials in the quality of available evidence. Similarly, about half of all cases had a previous history of heart disease, again with males more likely to have such history compared to females. Among the risk factors of importance, about 40.35% of IHD deaths had a prior history of hypertension. Overall, 44.11% of the deceased had a positive history of smoking, but more importantly, almost three-fourths of the male IHD deaths had ever smoked. The average recall period for interviews was about four months, which is within the recommendations for VA.

| Variable | Female | Male | Total | Chi-square | P value | ||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | P | ||

| Age | |||||||||

| < 30 | 2 | 1.2 | 3 | 1.3 | 5 | 1.3 | - | - | |

| 30-49 | 27 | 16.3 | 30 | 12.9 | 57 | 14.3 | - | 1.000 | |

| 50-69 | 70 | 42.2 | 123 | 52.8 | 193 | 48.4 | - | 1.000 | |

| 70+ | 67 | 40.4 | 77 | 33.0 | 144 | 36.1 | - | 1.000 | |

| All ages | 166 | 41.6 | 233 | 58.4 | 399 | 100 | |||

| Place of death | |||||||||

| Health facilities1 | 46 | 28.0 | 80 | 34.3 | 126 | 31.6 | - | - | |

| Home2 | 118 | 72.0 | 153 | 65.7 | 271 | 67.9 | 1.8 | 0.185 | |

| Medical history | |||||||||

| Hypertension | 74 | 44.6 | 87 | 37.3 | 161 | 40.4 | - | - | |

| Heart disease | 73 | 44.0 | 133 | 57.9 | 206 | 51.6 | 4.2 | 0.041a | |

| Diabetes | 20 | 12.0 | 30 | 12.1 | 50 | 12.5 | - | 0.516 | |

| Risk factors | |||||||||

| Smoking | 4 | 66.7 | 172 | 93.0 | 176 | 44.1 | - | - | |

| Alcohol | 2 | 33.3 | 13 | 7.0 | 15 | 3.8 | - | 0.072 | |

| Recall period in days | |||||||||

| Mean | 110 | 123 | - | - | |||||

| Median | 102 | 114 | 0 | 0.998 | |||||

Table 2 presents the distribution of IHD deaths according to the various categories of strength of diagnostic evidence. Only 4 cases mentioned a previous history of cardiac surgery associated with terminal cardiac symptoms, which represented the strongest possible evidence for IHD. In addition to these four cases, a substantial number of questionnaires included definitive information on terminal chest pain along with other symptoms, positive history, or a medical diagnosis of IHD, as defined in the Methods section. Together, these cases accounted for more than half the sample being assigned to the category of strong diagnostic evidence for IHD from VA.

In another 22% of cases, there was evidence that was reasonably suggestive of IHD, either in the form of terminal chest pain, or a combination of history of sudden death with previous heart disease or a medical diagnosis. While less convincing than the criteria defined for the category of strong evidence, we chose to allocate these cases to the “medium” strength of evidence category. For the remaining cases, the VA questionnaires only included minimal information either in the form of isolated clinical features such as sudden death, terminal shortness of breath, or previous history of heart disease or hypertension. In all these cases, the questionnaires did not contain any information suggestive of any other potential cause of death, but the absence of specific evidence of IHD necessitates these cases to be assigned the category of weak evidence. In two of the sampled cases, there was no symptom suggestive of any cause of death and were hence clearly incorrectly assigned to be caused by IHD.

We further analysed the data to evaluate the demographic and other factors that could be associated with the strength of evidence for the diagnosis of IHD. For this analysis, we combined the deaths from “strong” and “medium” evidence into one category termed “acceptable” evidence and compared it with those from the “weak” evidence category, as shown in Table 4. The analysis showed that while there was no association between strength of evidence and age at death, acceptable evidence to diagnose IHD was significantly associated with the occurrence of deaths in hospitals. Acceptable evidence was also positively associated with deaths in males as compared to deaths in females (Table 4), but a stratified analysis (Table 5) showed that this association was statistically significant only for male deaths that occurred at home (P = 0.005). More pertinent was the finding that there was a significant likelihood of recording better evidence if the respondent belonged to the same generation as the deceased (spouse or sibling), as compared to either a parent or offspring of the deceased being from a different generation. Paradoxically, acceptable evidence was significantly associated with longer recall periods (> 90 d), a finding that was also observed in the same population for a similar study conducted to assess the quality of evidence for VA diagnoses of cerebrovascular disease.

| Variable | Category | Evidence | Chi-square | P value | |||

| Acceptable | Weak | χ2 | P | ||||

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Sex of deceased | |||||||

| Male | 189 | 81.5 | 43 | 18.5 | - | - | |

| Female | 110 | 66.7 | 55 | 33.3 | 11.4 | < .001a | |

| Age of deceased | |||||||

| 30-69 | 191 | 76.4 | 59 | 23.6 | - | - | |

| 70+ | 106 | 74.1 | 37 | 25.9 | 0.3 | 0.627 | |

| Place of death | |||||||

| Hospital | 111 | 87.4 | 16 | 12.6 | - | - | |

| Home | 188 | 69.9 | 81 | 30.1 | 14.3 | < 0.001a | |

| Relationship between respondent and deceased | |||||||

| Spouse/sibling | 109 | 86.5 | 17 | 13.5 | - | - | |

| Parent/offspring | 126 | 69.6 | 55 | 30.4 | 11.8 | < 0.001a | |

| Respondent living with the deceased | |||||||

| Yes | 223 | 76.4 | 69 | 23.6 | - | - | |

| No | 69 | 70.4 | 29 | 29.6 | 0.2 | 0.281 | |

| Recall period | |||||||

| > 90 d | 172 | 80.0 | 43 | 20.0 | - | - | |

| ≤ 90 d | 122 | 70.1 | 52 | 29.9 | 4.4 | 0.036a | |

| Deaths in health facilities | Acceptable evidence | Weak evidence | Chi-square | ||||

| n | % | n | % | χ2 | P value | ||

| Male | 72 | 90.0 | 8 | 10.0 | - | - | |

| Female | 38 | 82.6 | 8 | 17.4 | - | 0.271 | |

| Deaths outside health facilities | |||||||

| Male | 117 | 77.0 | 35 | 23.0 | - | - | |

| Female | 71 | 60.7 | 46 | 39.3 | - | 0.005a | |

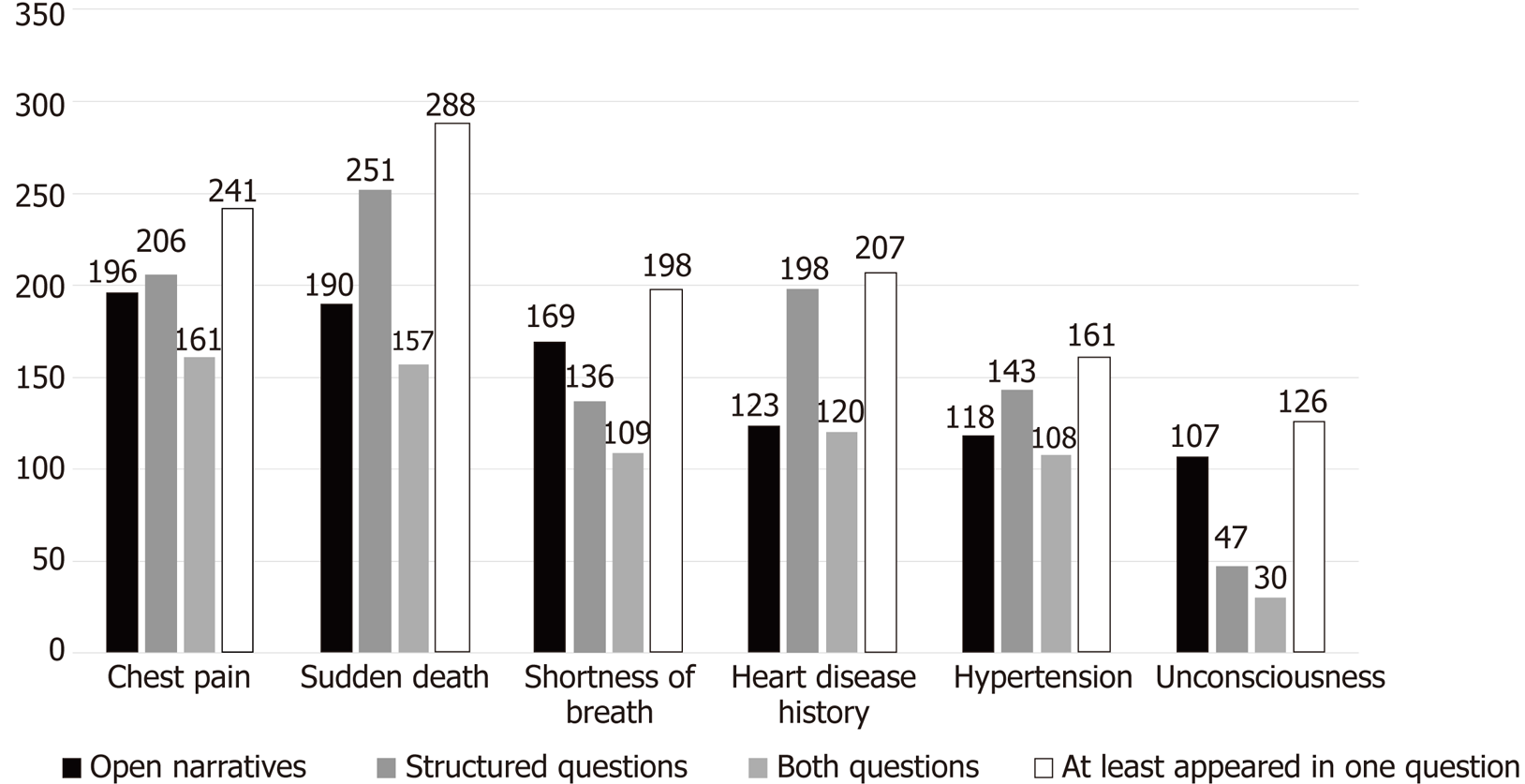

This study also analysed the availability and consistency of information across different sections of VA questionnaires. Figure 1 displays the frequencies of positive responses to several key variables from either or both the structured questions and open text sections of the questionnaire. Overall, there was the consistency of information across the two sources within the questionnaire in only 60%-70% of deaths for all of the key variables. The symptoms of chest pain, sudden death, and previous history of heart disease and hypertension were all reported more frequently in response to structured questions. In contrast, the symptoms of shortness of breath and unconsciousness were reported more often in the open text sections. A positive response in at least one source was used in assigning the category of strength of supporting evidence for each case.

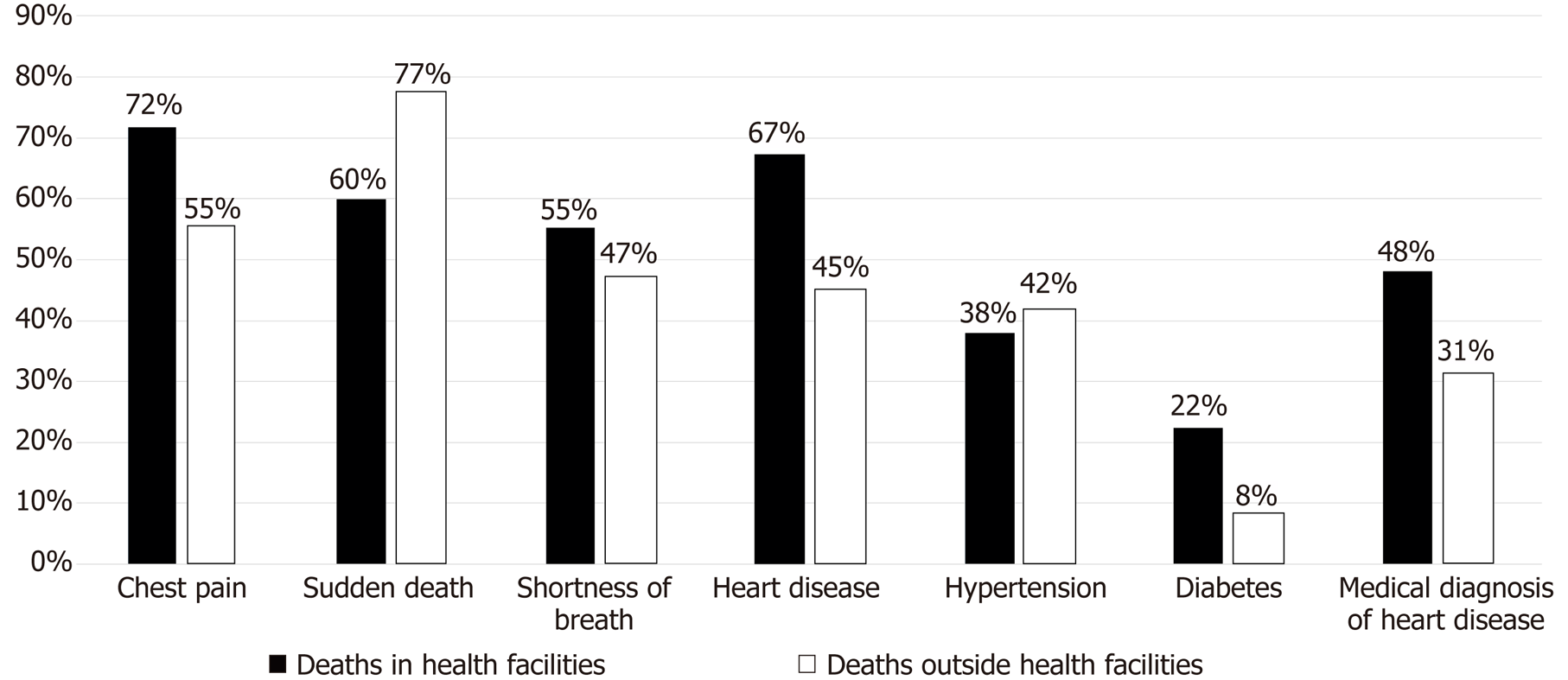

Another factor that could influence the quality of information in the VA questionnaires is whether the death took place in a health facility or at home. Figure 2 displays the proportions of deaths in these two locations for which a positive response was provided for certain key symptoms, as well as for the constructed variable “medical diagnosis of heart disease” (see Methods). As per usual expectation, respondents for deaths in health facilities provide higher levels of positive responses, indicative of increased awareness of the clinical features of the terminal illness, likely communicated by the health care staff. This is also evident in the higher proportions of cases with a medical diagnosis of heart disease, as recorded in the questionnaire. All of these observations support the general finding of significantly higher levels of acceptable evidence for deaths in hospitals, as reported in Table 4.

VA is currently being promoted as a viable option for deriving information on causes of death in countries where medical certification of cause of death is unavailable or limited[21]. Despite methodological limitations of VA in terms of its reliance on second-hand information from the deceased’s relatives, which follows a considerable recall period, causes of death from VA are increasingly being used for national mortality estimation[22,23]. IHD is estimated to be among the top five leading causes of death in the world, as well as in Indonesia. To our knowledge, this study provides the first ever empirical assessment of the quality of evidence available to infer a diagnosis of ischaemic heart disease as the underlying cause of death from VA. Our study identified that more than half (53%) of sample questionnaires from the Indonesian SRS contained strong evidence about IHD. Furthermore, another 22% of cases included sufficient evidence to support a diagnosis of IHD. For the remaining one fourth of the sample, although the evidence used to assign IHD was weak, there was no evidence in the questionnaires to indicate an alternative VA-based cause of death. Overall, our study findings indicate that VA protocols employed in the Indonesian SRS generate evidence of sufficient quality for diagnosing IHD as an underlying cause of death, but with some room for improvement.

More detailed analyses identified that there was a significant likelihood for acceptable diagnostic evidence of IHD from VA for deaths that occurred in health facilities, among male deaths at home, or for which the respondents were from the same generation as the deceased. The availability of strong evidence for hospital deaths is generally plausible and readily understood, owing to the potential for family members to receive direct medical information about the illness from medical staff, which was observed for both male and female deaths. However, for deaths at home, there was a significantly higher proportion of male deaths with acceptable evidence compared to female deaths. In general, it was also observed that the quality of evi-dence was uniformly better from wives as respondents, in comparison with hus-bands as respondents (data not shown). This could be a reason for the gender diffe-rentials in the quality of evidence. More detailed qualitative research is required to ascertain the reasons for this difference in response patterns. Also, the finding that respon-dents from the same generation (either a spouse or sibling) as the deceased are associated with better quality of VA evidence as compared to either the parents or offspring (a different generation) of the deceased is important. This finding suggests that for adult deaths, interviewers should actively seek and preferably conduct the VA with a spouse or sibling, rather than other adult relatives who may not pay the sa-me attention to details of the terminal illness or the health care received by the deceased.

From a diagnostic perspective, IHD poses particular challenges, in that its cardinal symptom - acute chest pain - is essentially subjective in nature, as compared to the directly observable unilateral paralysis in cases of cerebrovascular stroke. The subjective nature of the occurrence, intensity, and duration of chest pain makes it challenging for VA respondents to report this symptom, as evidenced from its reporting in only about 60% of deaths. This is further compounded by the incidence of sudden death in IHD, which is mostly due to cardiac causes as compared to cerebrovascular stroke[24]. In the SRS VA protocol, the structured question on ‘sudden death’ enquires about the occurrence of death in an individual without any serious illness in the period immediately preceding 24 h. The response to this question also has a degree of subjectivity, which gets further blurred by the length of the recall period. Also, there needs to be clarity in the interviewer’s understanding of the phenomenon of sudden death, and (s)he should be able to clearly convey this concept to the respondent, in order to elicit and record the correct response. In our study sample, sudden death was reported in over 70% of cases. In the absence of a medical certificate of cause of death, we considered that a verbal confirmation of chest pain and sudden death is highly suggestive of the cause being IHD. A third important element in our diagnostic criteria was the availability of a “medical diagnosis”, as defined in the methods. The SRS interview protocol gives strict instruction to interviewers to not ask leading questions naming specific causes when recording the open narrative, or the structured questions on health care access, or diagnoses provided by healthcare staff. Further, a diagnosis of IHD recorded in the VA reviewing physician’s summary is either based on his opinion from the questionnaire review or from prior knowledge of the deceased’s clinical history. Hence, taken together, these three elements - chest pain, sudden death, and a medical diagnosis - formed the core criteria for strong evidence in support of an IHD diagnosis. Other categories of evidence included less specific features for IHD.

In terms of the availability of direct clinical information, only four cases reported a previous history of cardiac surgery. Also, there was no information from the health records section providing diagnostic evidence from previous hospital discharge documents, electrocardiograms, laboratory or imaging test reports, or drug prescriptions, which could have aided us in evaluating the strength of evidence. Such information was not available, even though a third of the study sample deaths occurred in hospitals, for which the only useful information from the health records section was from the cause of death communicated by the health staff. A recent study in Vietnam identified that clinical discharge records are valuable evidence for deaths in individuals who accessed health facilities but died within a month following discharge[25]. A likely reason for the absence of this information in Indonesia is the cultural practice of disposing all medical documents and health care materials belonging to the deceased at the time of or soon after the funeral. Future community sensitization events about the VA program could appeal for such documentation to be preserved and made available during VA enquiries.

The findings on the availability and consistency of information from different sections of the VA questionnaire also have important implications for VA implementation. The two main questionnaire components comprising the open text sections and structured questions offer opportunities to record similar information for certain key variables potentially. This provision has been made in the questionnaires to accommodate an observed inherent variability in response patterns during VA interviews, as demonstrated both in our study (Figure 1) as well as in a similar study that only assessed such variation in the reporting of paralysis in deaths from cerebrovascular stroke in Vietnam[26]. Some respondents require prompting through structured questions to elicit all relevant information, while others are more comfortable with giving information in their own words and are non-committal or even inattentive during the structured questions. The open narrative section in questionnaires has generally been found to be very important in determining the cause of death, similar to studies conducted elsewhere[27,28]. Constructing a timeline that puts the history of disease, individual symptoms, signs, and chronology of clinical events together can help characterise the events leading to death, if the respondents were familiar with the deceased. In the Indonesian VA physician review protocol, reviewers are also trained to utilise the information from all sections of the questionnaire to construct such a summary, in order to guide their diagnostic decisions. In many instances, it is likely that physician reviewers would be able to diagnose causes of death largely from the open narratives, although they should always seek corroborating information from the structured questions. Ultimately, better consistency of information across both sources increases confidence in the veracity of information available to formulate diagnoses.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates a process for reviewing the quality of evidence in VA questionnaires, in the context of assigning ischaemic heart disease as the underlying cause of death. While acceptable evidence was available for three-fourths of the cases in our study sample, several measures could be taken to improve overall data quality. Firstly, the questionnaire could be modified to elicit more detail in regard to the designation and/or qualification of health staff (doctors, nurses, or paramedics) who provided an opinion as to the cause of death for events in health facilities. This would enable more accurate use of this information in deciding the level of evidence. Secondly, communities should be sensitised to the benefit of retaining and sharing available health care documents within the household with the local health centre staff, instead of casual disposal following the final rites. Thirdly, the SRS program could initiate activities to liaise with secondary and tertiary hospitals in cities and major towns in the proximity of SRS sites, from where some cause of death-related data may be obtained for facility deaths. Eventually, medical certification of the cause of death scheme could be introduced in these hospitals, to improve the overall quality of evidence for mortality statistics from the SRS. Also, further qualitative research could help design improved community interactions to access the most appropriate respondent, as well as improved interviewing techniques to strengthen VA data quality. These study methods for ischaemic heart disease could be used as a model to investigate the quality of evidence for other major causes of death such as cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, tuberculosis, and chronic lung disease, among others, in Indonesia as well as other settings where VA is routinely implemented. Periodic evaluation of the quality of VA evidence is essential to improve the empirical use of VA data for mortality and cause of death measurements for health policy, monitoring, and evaluation.

Mortality and cause of death data are the basis for health policy and research. The Civil Registration and Vital Statistics (CRVS) system is the ideal source of data, but the CRVS in Indonesia is still under development. Since 2014, the National Sample Registration System (SRS) has provided nationally representative mortality data from 128 sub-districts. Verbal autopsy (VA) is used in SRS to obtain the cause of death.

The evidence available from the VA to diagnose causes of death must be assessed to establish the reliability and utility of SRS data. The diagnosis of VA may be influenced by many factors, such as questionnaire design, interviewer skills, characteristics of respondents (including proximity to the deceased), recall period for interviews, and methods for determining the cause of death. Given these potential sources of bias, the World Health Organization recommends conducting scientific research to assess the quality of VA’s cause of death, hence necessitating this study.

This study was designed to assess the quality of evidence used to diagnose Ischaemic Heart Disease (IHD) as a cause of death from VA. The study also sought to evaluate various factors that could influence the quality of evidence, such as age and gender of the deceased, place of death, relationship of the respondent, and recall period.

The study sample comprised a random sample of 400 deaths out of a total of 4,070 cases diagnosed from IHD in the SRS data for 2016. A data extraction form and data entry template were designed to collect relevant IHD data from VA questionnaires. A standardised classification was designed to IHD cases to categories with strong, medium and weak evidence. Strong evidence of IHD was defined to include surgery for coronary heart disease, or the history of chest pain along with two additional characteristics among sudden death; history of heart disease; the medical diagnosis of heart disease; or terminal shortness of breath. Statistical analysis was conducted to assess the frequency of cases with different levels of evidence, as well as to identify associations between case characteristics and levels of evidence.

Nearly half of all IHD deaths were concentrated in the 50-69 age group (48.40%), and another 36.10% were 70-years-old or older. Two-thirds of the deceased were male (58.40%). VA questionnaires for about three-quarters of all cases contained strong or medium evidence to diagnose IHD. Quality of evidence was significantly associated with the occurrence of deaths in hospitals, with male deaths at home, and with deaths for which the respondent belonged to the same generation as the deceased.

VA diagnoses of IHD was found to be based on acceptable evidence in the majority of cases in the study sample. Attention is required to improve recording of information during VA interviews, particularly in regard to correct interpretation of responses for symptoms and signs, and more importantly, clinical details from interactions with health services. Such studies should be conducted for other leading causes of death in Indonesia, as well as across space and time.

The study assessed levels and determinants of the quality of diagnostic evidence to assign Ischaemic Heart Disease as a cause of death from VA methods in Indonesia. The study results provided perspectives on VA data collection processes, evidence patterns guiding VA diagnosis, and the influence of various circumstances of the death event and household interview on the overall quality of evidence from VA.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Cardiac and cardiovascular systems

Country of origin: Australia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ueda H S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Ruzicka LT, Lopez AD. The use of cause-of-death statistics for health situation assessment: national and international experiences. World Health Stat Q. 1990;43:249-258. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Mahapatra P, Shibuya K, Lopez AD, Coullare F, Notzon FC, Rao C, Szreter S; Monitoring Vital Events. Civil registration systems and vital statistics: successes and missed opportunities. Lancet. 2007;370:1653-1663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | World Health Organization. Strengthening civil registration and vital statistics through innovative approaches in the health sector. Geneva; 2014. Report No: WHO/HIS/HSI/2014/1. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/protection/files/Strengthening_Civil_Registration_and_Vital_Statistics_Systems_through_Innovative_Approaches_in_the_Health_Sector.pdf. |

| 4. | Rao C. Breathing life into mortality data collection. Science. 2011;333:1702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pratiwi ED, Kose S. Development of an Indonesian sample registration system: A longitudinal study. The Lancet. 2013;381:S118. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Vital Statistics (Sample Registration System) Division. Sample Registration System New Delhi: Vital Statistics Division, Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India; 2007. Available from: http://www.censusindia.gov.in/Vital_Statistics/SRS/Sample_Registration_System.aspx. |

| 7. | Yang G, Hu J, Rao KQ, Ma J, Rao C, Lopez AD. Mortality registration and surveillance in China: History, current situation and challenges. Popul Health Metr. 2005;3:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bangladeh Bureau of Statistics. Report on Bangladesh Sample Vital Registration System 2010. Dhaka: Statistics Division: Ministry of Planning; 2012; Available from: http://203.112.218.65:8008/WebTestApplication/userfiles/Image/LatestReports/SVRS-10.pdf. |

| 9. | Usman Y, Iriawan R, Rosita T, Lusiana M, Kosen S, Kelly M, Forsyth S, Rao C, Indonesia’s sample registration system in 2018: A work in progress. JPSS. 2019;27:39-52. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fottrell E, Byass P. Verbal autopsy: methods in transition. Epidemiol Rev. 2010;32:38-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | World Health Organization. Verbal autopsy standards: ascertaining and attributing cause of death. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007; Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/verbalautopsystandards/en/index3.html. |

| 12. | de Savigny D, Riley I, Chandramohan D, Odhiambo F, Nichols E, Notzon S, AbouZahr C, Mitra R, Cobos Muñoz D, Firth S, Maire N, Sankoh O, Bronson G, Setel P, Byass P, Jakob R, Boerma T, Lopez AD. Integrating community-based verbal autopsy into civil registration and vital statistics (CRVS): system-level considerations. Glob Health Action. 2017;10:1272882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chandramohan D, Maude GH, Rodrigues LC, Hayes RJ. Verbal autopsies for adult deaths: issues in their development and validation. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23:213-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Joshi R, Kengne AP, Neal B. Methodological trends in studies based on verbal autopsies before and after published guidelines. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:678-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nichols EK, Byass P, Chandramohan D, Clark SJ, Flaxman AD, Jakob R, Leitao J, Maire N, Rao C, Riley I, Setel PW; WHO Verbal Autopsy Working Group. The WHO 2016 verbal autopsy instrument: An international standard suitable for automated analysis by InterVA, InSilicoVA, and Tariff 2.0. PLoS Med. 2018;15:e1002486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Misganaw A, Mariam DH, Araya T, Aneneh A. Validity of verbal autopsy method to determine causes of death among adults in the urban setting of Ethiopia. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ganapathy SS, Yi Yi K, Omar MA, Anuar MFM, Jeevananthan C, Rao C. Validation of verbal autopsy: determination of cause of deaths in Malaysia 2013. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Moriyama IM, Dawber TR, Kannel WB. Evaluation of diagnostic information supporting medical certification of deaths from cardiovascular disease. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1966;19:405-419. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Moriyama IM, Baum WS, Haenszel WM, Mattison BF. Inquiry into diagnostic evidence supporting medical certifications of death. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1958;48:1376-1387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rao C, Yang G, Hu J, Ma J, Xia W, Lopez AD. Validation of cause-of-death statistics in urban China. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:642-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kirkwood BR, Sterne JA. Calculation of required sample size. Essential Medical Statistics. Massachusetts: Blackwell Science Ltd 2003; 413-428. |

| 22. | Garenne M, Fauveau V. Potential and limits of verbal autopsies. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. Available from: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/84/3/editorial30306html/en/. |

| 23. | Jha P, Gajalakshmi V, Gupta PC, Kumar R, Mony P, Dhingra N, Peto R; RGI-CGHR Prospective Study Collaborators. Prospective study of one million deaths in India: rationale, design, and validation results. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hoa NP, Rao C, Hoy DG, Hinh ND, Chuc NT, Ngo DA. Mortality measures from sample-based surveillance: evidence of the epidemiological transition in Viet Nam. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:764-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Adabag AS, Luepker RV, Roger VL, Gersh BJ. Sudden cardiac death: epidemiology and risk factors. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:216-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tran HT, Nguyen HP, Walker SM, Hill PS, Rao C. Validation of verbal autopsy methods using hospital medical records: a case study in Vietnam. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gupta S, Khieu TQ, Rao C, Anh N, Hoa NP. Assessing the quality of evidence for verbal autopsy diagnosis of stroke in Vietnam. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2012;3:267-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Polprasert W, Rao C, Adair T, Pattaraarchachai J, Porapakkham Y, Lopez AD. Cause-of-death ascertainment for deaths that occur outside hospitals in Thailand: application of verbal autopsy methods. Popul Health Metr. 2010;8:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |