Published online Sep 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i9.598

Peer-review started: April 5, 2016

First decision: May 23, 2016

Revised: July 14, 2016

Accepted: July 29, 2016

Article in press: August 1, 2016

Published online: September 27, 2016

Processing time: 180 Days and 5.4 Hours

Acute severe ulcerative colitis (UC) is a highly morbid condition that requires both medical and surgical management through the collaboration of gastroenterologists and colorectal surgeons. First line treatment for patients presenting with acute severe UC consists of intravenous steroids, but those who do not respond require escalation of therapy or emergent colectomy. The mortality of emergent colectomy has declined significantly in recent decades, but due to the morbidity of this procedure, second line agents such as cyclosporine and infliximab have been used as salvage therapy in an attempt to avoid emergent surgery. Unfortunately, protracted medical therapy has led to patients presenting for surgery in a poorer state of health leading to poorer post-operative outcomes. In this era of multiple medical modalities available in the treatment of acute severe UC, physicians must consider the advantages and disadvantages of prolonged medical therapy in an attempt to avoid surgery. Colectomy remains a mainstay in the treatment of severe ulcerative colitis not responsive to corticosteroids and rescue therapy, and timely referral for surgery allows for improved post-operative outcomes with lower risk of sepsis and improved patient survival. Options for reconstructive surgery include three-stage ileal pouch-anal anastomosis or a modified two-stage procedure that can be performed either open or laparoscopically. The numerous avenues of medical and surgical therapy have allowed for great advances in the treatment of patients with UC. In this era of options, it is important to maintain a global view, utilize biologic therapy when indicated, and then maintain an appropriate threshold for surgery. The purpose of this review is to summarize the growing number of medical and surgical options available in the treatment of acute, severe UC.

Core tip: The numerous avenues of medical and surgical therapy have allowed for great advances in the treatment of patients with ulcerative colitis. In this era of options, it is important to maintain a global view, utilize corticosteroids and rescue therapy when indicated, and then maintain an appropriate threshold for surgery. Colectomy remains a viable and often life-saving treatment and should not be viewed as the “therapy of last resort”.

- Citation: Andrew RE, Messaris E. Update on medical and surgical options for patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis: What is new? World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(9): 598-605

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i9/598.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i9.598

Acute severe ulcerative colitis (UC) is an exacerbation of a chronic condition characterized by inflammation of the colonic mucosa extending from the rectum proximally to varying portions of the large intestine. UC is a highly morbid condition that requires both medical and surgical management. Prior to the 1950’s and the implementation of urgent colectomy and systemic steroids, mortality rates were as high as 70% in patients with severe UC[1]. In recent years, mortality rates have dropped to less than 1% with the combination of medical therapy, rescue therapy, and timely total abdominal colectomy (TAC) when indicated[2,3]. Despite the introduction of rescue therapies such as cyclosporine (calcineurin inhibitor) and infliximab [tumor necrosis factor (TNF) monoclonal antibody] in the treatment regimen of patients with severe UC, colectomy rates have remained stable (27%) for the past thirty years[4].

Historically, severe UC has been defined as the passage of at least six daily bloody stools, along with any of the following signs of systemic disease: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate > 30 mm/h, temperature > 37.8 °C, pulse rate > 90/min and hemoglobin < 10.5 g/dL (truelove and witts criteria)[5]. Lichtiger created a scoring system for severe UC based on frequency of stools, nocturnal diarrhea, blood in stool, fecal incontinence, and abdominal pain[6]. These criteria play a significant role in the decision to escalate therapy or proceed to colectomy in patients with severe disease. Rates of TAC within the first five years of disease range from 9%-35%, even with medical therapy[7]. With a growing number of options available to both gastroenterologists and surgeons in the management of UC, treatment is becoming more individualized and variable. The following review provides a description of current medical and surgical management of acute severe UC.

Patients presenting with signs of acute severe UC require immediate admission to the hospital. They must have regular monitoring of vital signs and urine output as well as a comprehensive laboratory workup. Initial tests on admission should include a comprehensive metabolic panel, pre-albumin, albumin, complete blood count, and inflammatory markers [erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein (CRP)][5]. A tuberculin skin test should also be performed on that admission in preparation for possible treatment with immunosuppressant or biologic agents. Abdominal imaging should be obtained to evaluate for colonic dilation (greater than 5.5 cm) on plain X-ray or computed tomography scan, and the patient should be monitored for fever, leukocytosis and other signs of systemic sepsis that accompany toxic megacolon[8,9].

Stool cultures and a clostridium difficile assay must be obtained to exclude infectious pseudomembranous colitis, and the frequency and consistency of bowel movements should be recorded.

Patients should take nothing by mouth and should be fluid resuscitated to a goal of 0.5 mL/kg per hour of urine output. The administration of intravenous fluids and the correction of electrolyte imbalances prevent dehydration and worsening of colonic dysmotility and dilatation[10]. All patients who are not bleeding should be given thromboembolic prophylaxis due to the increased risk of thrombosis in the setting of systemic inflammation. In addition, the patient should undergo flexible sigmoidoscopy to confirm the diagnosis of acute severe UC and to obtain biopsies to rule out cytomegalovirus colitis[11].

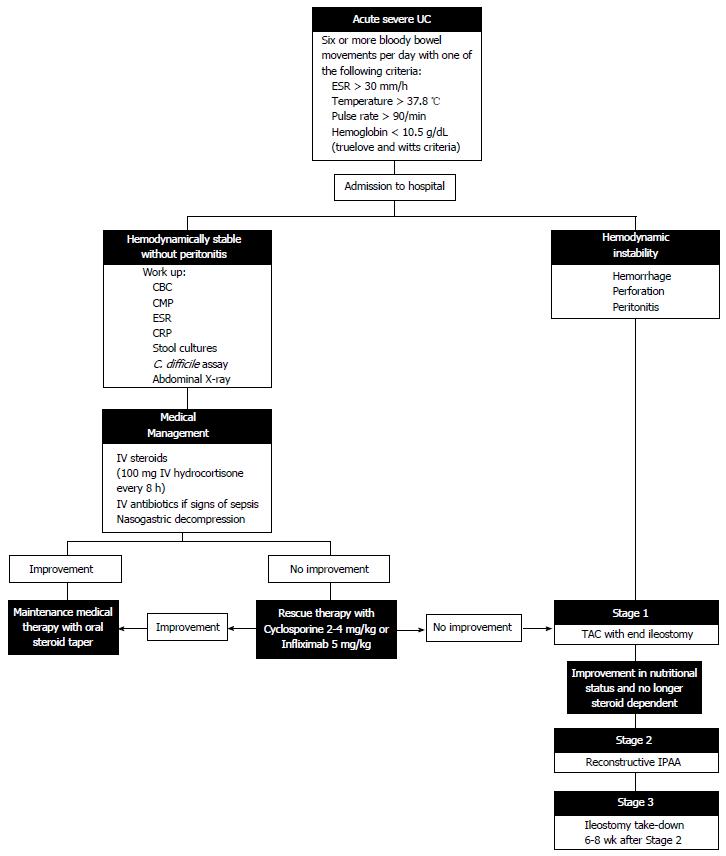

Patients with acute severe UC require constant reassessment, with antibiotic administration in the setting of infection, total parenteral nutrition in the setting of malnutrition, and escalation of therapy to medication non-responders. Kedia et al[12] proposed an algorithm for reassessing patient steroid response at days 1, 3 and 4-7 in which incomplete responders and non-responders either advance to rescue therapy or proceed to colectomy. In this algorithm, the Oxford criteria (> 8 stools/d or > 3 stools/d with a CRP > 45 mg/L) are used to determine the need for escalation of therapy[13]. With careful attention to the patient’s physical condition and severity of illness, the appropriate medical or surgical therapy can be selected to target the individual’s ever-changing disease (Figure 1).

Corticosteroids were introduced in the management of UC in the 1950’s, though the first clinical trial proving their efficacy was not published until the 1970’s[5,14]. For the past 40 years, intravenous corticosteroids (methylprednisolone 60 mg/d or hydrocortisone 100 mg/8 h) for a 7-10 d course have been a cornerstone in the treatment of acute severe UC[4,14]. A large review and meta-analysis reported the response to IV steroids to be 67% with short term colectomy rate of 29%[4].

Rescue therapies made their first appearance in the medical management of UC in the 1990’s with the introduction of cyclosporine. Infliximab followed soon after as an alternative therapy with a different side-effect profile that could also serve as a salvage therapy in the setting of UC refractory to corticosteroids.

Cyclosporine (2-4 mg/kg) has been shown to induce remission in 60%-80% of patients with acute severe colitis, but colectomy rates at four months remain close to 50% unless the patient is successfully bridged to maintenance therapy[6,15,16]. The role of infliximab in the treatment of non-acute, moderate-to-severe UC has been reported in the Active Ulcerative Colitis Trials 1 and 2, with response rates between 61% and 69%[17]. Infliximab (5 mg/kg) has also been shown to significantly decrease rate of colectomy at three months for patients with severe to moderate attacks of UC[18]. In an Italian trial by Kohn et al[19] there was an 85% response rate to infliximab with no colectomy in the 2 mo following hospital admission for acute severe UC and 67% at 23 mo. Multiple studies have compared infliximab and cyclosporine as rescue therapy for acute severe UC with no significant difference between the two therapies. Colectomy rates were similar at three and twelve months between patients receiving infliximab (31% and 41%) and cyclosporine (30% and 44%)[20,21]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis compared infliximab and cyclosporine as rescue therapy and found no significant difference in 3 or 12 mo colectomy rates among three randomized trials but reported significantly increased response to treatment and lower 12 mo colectomy rate among 12 non-randomized studies[22].

While immunosuppressant and biologic agents have become established means of treating severe UC, there is conflicting evidence on the use of sequential therapy. Reports of the use of infliximab after failing steroids and cyclosporine have shown a 30% colectomy rate[23]. A review of 10 studies in which rescue therapies were used sequentially for treatment of acute severe UC demonstrated colectomy rates of 28% at 3 mo and 42% at 12 mo with a 23% rate of adverse events-lower than previously reported in the literature[24]. At this time, the selection of a rescue therapy agent, cyclosporine vs infliximab vs one agent following the other, is based primarily on physician comfort and experience, along with patient tolerance of side effects and susceptibility to infection.

Although not currently the standard of care, vedolizumab, an integrin antibody, has been shown to induce steroid-free remission in approximately one third of UC patients who have failed anti-TNF therapy[25]. Further investigation is required before recommendations can be made for its use in the treatment of acute severe UC.

Other agents such as thiopurines and methotrexate play a role in maintenance therapy and steroid dose reduction, but these drugs have shown no significant success as induction therapy to achieve remission in patients with active UC[26,27].

The role of antibiotics in the treatment of acute severe UC remains limited because even in severe UC there is no proven therapeutic benefit to oral or intravenous metronidazole, tobramycin, ciprofloxacin or vancomycin[28-30]. Only in the setting of active infection or for pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis do 2012 ECCO guidelines recommend that antibiotics be administered[31].

Although tremendous advances have been made in the medical treatment of UC, colectomy remains a cornerstone in the management of this disease. Overall, the rates of colectomy have not significantly changed since the addition of rescue therapies to the armamentarium of gastroenterologists. Predictors of the need for second-line treatment or colectomy are numerous, but several variables, including severity of disease, stool frequency, CRP, hyopoalbuminemia (< 3 mg/dL), and radiographic evidence of colonic dilation (> 5.5 cm), all can be used in early identification of the need for escalation of therapy[32-34]. A more recent scoring system also includes the need for blood transfusions or parenteral nutrition as predictors of need for colectomy[35].

Due to the growing number of medical therapies for severe UC, patients are being referred for colectomy later after multiple attempts at medical salvage. These patients present in a poorer state of health, malnourished and anemic, and the delay is not without consequences.

Patients who undergo an operation after receiving high dose steroids or who are malnourished often have increased surgical complications[36]. Post-operative complications include anastomotic leak, stricture, fistulae, and bowel obstruction. One study reported the rate of post-operative complications to be over three times higher, with the rate of sepsis being 13 times higher, in patients undergoing three-stage ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) after treatment with infliximab[37]. Similarly, significantly higher rates of major complications were found in patients undergoing longer duration of medical therapy (> 8 d) in a group of 80 patients with severe UC followed over the course of 7 years[13].

The importance of continuous reassessment of the need for surgery is emphasized due to the mortality benefits of a well-timed or elective operation; mortality rates three years after elective colectomy (3.7%) are significantly lower than after admission without surgery (13.6%) or with emergent surgery (13.2%) in patients with acute severe UC[38].

Surgical management of UC in the setting of failed medical therapy involves the performance of a TAC with an optional IPAA in two or three stages[3]. In a three-stage approach, the initial operation involves a subtotal or TAC with creation of an end ileostomy. The stapled or hand-sewn rectosigmoid stump can be sutured as a mucous fistula to the distal aspect of the abdominal wall incision, may be closed and sutured to the subcutaneous tissue, or may be left unattached in the pelvis. The primary reason for creation of a mucous fistula or placement of the long rectal stump in the subcutaneous tissue is to avoid rectal stump breakdown and leakage with subsequent pelvic sepsis, especially in cases of severe inflammation and thickening of tissue[39]. The drawback to a mucous fistula lies in patient dissatisfaction that may occur with persistent discharge during the long-term recovery period[40]. The manner in which the rectosigmoid is closed depends mainly upon patient anatomy and surgeon preference, but transanal rectal decompression is commonly performed following all techniques[3]. TAC with end ileostomy as the first stage allows for immediate diversion of the fecal stream, avoids the dangers of a pelvic dissection or anastomosis in a critically ill patient, and allows for preservation of the rectum with the possible diagnosis of Crohn’s colitis rather than UC.

The second stage of the procedure involves pouch formation with diverting ileostomy. Restorative procto–colectomy with IPAA is an elective operation performed in the absence of toxicity or severe malnutrition. Although proximal diversion does not prevent pelvic sepsis in the setting of IPAA, diverting ileostomy has been shown to lessen complications related to anastomotic leakage[41,42]. The procedure can be technically challenging and involves identification of the rectal stump with full mobilization to the level of the levator ani muscles, proctectomy, and construction of a J-shaped pouch through a side-to-side anastomosis of the distal 40 cm of terminal ileum[43]. Although several pouch designs have been promoted over the years, including the S-pouch and the W-pouch, the J-pouch has endured due to its relatively simple construction and equivalent or superior outcomes to other designs[43,44]. The IPAA may be stapled or hand-sewn but fewer complications and better long-term quality of life have been reported in patients undergoing stapled anastomosis[45].

The third stage of the procedure involves takedown of the diverting ileostomy and reestablishment of intestinal continuity. This final step should only be performed after water-soluble contrast enema has demonstrated patency and anastomotic integrity of the pouch.

In rare cases (5%), patients present with rectal sparing disease, and TAC with end ileostomy remains the first step to patient recovery[46]. Only in these specific cases has ileorectal anastomosis as an alternative to pouch formation been described for reconstruction of the gastrointestinal tract[47].

Although colectomy and pouch formation may be and are routinely performed as one procedure, this operation is reserved for UC patients who are healthy, well-nourished, off steroids and not experiencing an acute flare[41]. Performing a three stage procedure allows for healthier, better nourished patients at the time of surgery[48]. Some centers have attempted to abbreviate the hospital course of acute severe UC patients by performing a modified two-stage procedure (colectomy followed by IPAA and ileostomy takedown). Zittan et al[49] demonstrated significantly lower rates of anastomotic leak (4.6% vs 15.7%) when comparing modified 2-stage IPAA to the traditional 2-stage procedure (colectomy with pouch formation followed by ileostomy takedown). Swenson et al[50] demonstrated equivalent patient outcomes with significantly lower hospital cost in patients with resolved severe colitis after colectomy who underwent a modified two-stage IPAA vs a three-stage procedure. The cost of medical therapy is not only affected by the operation performed but also by the timing of the procedure. In a comparison of patients with severe UC undergoing early colectomy with IPAA vs standard medical therapy, Park et al[51] reported a cost analysis showing a $90000 increase in cost to patients who received prolonged medical salvage therapy with very little improvement in quality of life.

A laparoscopic approach to TAC in severe UC patients provides a reasonable alternative to the open approach and has been shown to be equally safe and feasible in comparison[52]. While the laparoscopic approach has the advantage of reducing post-operative pain, time to stoma function, and overall hospital stay, it also leads to longer operative time and may be more technically demanding for the surgeon[53,54].

Although the ileal pouch does allow many patients to have a more normal life-style and defecation pattern, the procedure is not without enduring consequences. A recent study from the Cleveland Clinic published long-term outcomes of 74 patients who underwent IPAA and were followed over a 20-year period. Pouch-specific complications included pouchitis (45%), stricture (16%), fistula (30%), obstruction (20%), and change of diagnosis to Crohn’s (28%). Long-term consequences of the procedure also included frequent stooling requiring anti-diarrheal medication (44%) and difficulty conceiving (25% and all women)[44]. Pouch failure rates at 10 and 20 years have been reported to be 9% and 14%, although a 2016 study reported a failure rate of 2.4%, indicating that pouch outcomes may be improving[44,55,56]. The three stage approach with proximal diversion may be associated with better outcomes as it reduces the impact that complications such as pelvic sepsis or anastomotic leak have on the ultimate quality of the pouch[41].

While a substantial number of UC patients do elect to undergo IPAA after TAC, this procedure is not mandatory, and many choose to forgo the pouch completely. A Swedish cohort study of over 2000 patients who underwent colectomy for inflammatory bowel disease showed that less than half (43%) of the patients underwent reconstructive surgery over a ten year period[57]. A 2015 review of UC patients with an end ileostomy or IPAA demonstrated equivalent improvement in quality of life at 1 year with the majority of the benefit related to the control of disease symptoms[58].

The optimal treatment algorithm in the management of severe UC remains controversial. The purpose of this review is to summarize the current medical and surgical options available in the treatment of acute, severe UC.

First line treatment for patients presenting with acute severe UC consists of intravenous steroids, but those who do not respond require escalation of therapy or emergent colectomy. The mortality of emergent colectomy has declined significantly in recent decades, but due to the morbidity of this procedure, second line agents such as cyclosporine and infliximab have been used as rescue therapy in an attempt to avoid emergent surgery. In this era of multiple medical modalities available in the treatment of acute severe UC, it is imperative that physicians consider the advantages and disadvantages of prolonged medical therapy in an attempt to avoid surgery. Colectomy remains a mainstay in the treatment of severe ulcerative colitis not responsive to corticosteroids and rescue therapy, and timely referral for surgery allows for improved post-operative outcomes with lower risk of sepsis and improved patient survival.

Options for reconstructive surgery include three-stage IPAA or a modified two-stage procedure. The three-stage procedure offers the advantage of a healthier, well-nourished patient, but the two-stage procedure offers fewer in-hospital days and decreased overall cost.

The numerous avenues of medical and surgical therapy have allowed for great advances in the treatment of patients with UC. In this era of options, it is important to maintain a global view, utilize rescue therapy when indicated, and then maintain an appropriate threshold for surgery. Colectomy remains a viable and often life-saving treatment and should not be viewed as the “therapy of last resort”.

We would like to acknowledge Lisa McCully, Projects Specialist, for her assistance in designing Figure 1.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Madnani MA, Matowicka-Karna J S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Hardy TL, Bulmer E. Ulcerative Colitis: A Survey of Ninety-five Cases. Br Med J. 1933;2:812-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dayan B, Turner D. Role of surgery in severe ulcerative colitis in the era of medical rescue therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3833-3838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Brown SR, Haboubi N, Hampton J, George B, Travis SP. The management of acute severe colitis: ACPGBI position statement. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10 Suppl 3:8-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Turner D, Walsh CM, Steinhart AH, Griffiths AM. Response to corticosteroids in severe ulcerative colitis: a systematic review of the literature and a meta-regression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:103-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 495] [Cited by in RCA: 451] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Truelove SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. Br Med J. 1955;2:1041-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1832] [Cited by in RCA: 1868] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, Gelernt I, Bauer J, Galler G, Michelassi F, Hanauer S. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1841-1845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1217] [Cited by in RCA: 1174] [Article Influence: 37.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, Binder V. Colorectal cancer risk and mortality in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1444-1451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Trudel JL, Deschênes M, Mayrand S, Barkun AN. Toxic megacolon complicating pseudomembranous enterocolitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:1033-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Seah D, De Cruz P. Review article: the practical management of acute severe ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:482-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gan SI, Beck PL. A new look at toxic megacolon: an update and review of incidence, etiology, pathogenesis, and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2363-2371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Criscuoli V, Casà A, Orlando A, Pecoraro G, Oliva L, Traina M, Rizzo A, Cottone M. Severe acute colitis associated with CMV: a prevalence study. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:818-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kedia S, Ahuja V, Tandon R. Management of acute severe ulcerative colitis. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2014;5:579-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Randall J, Singh B, Warren BF, Travis SP, Mortensen NJ, George BD. Delayed surgery for acute severe colitis is associated with increased risk of postoperative complications. Br J Surg. 2010;97:404-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Truelove SC, Jewell DP. Intensive intravenous regimen for severe attacks of ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 1974;1:1067-1070. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Cheifetz AS, Stern J, Garud S, Goldstein E, Malter L, Moss AC, Present DH. Cyclosporine is safe and effective in patients with severe ulcerative colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:107-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Fornaro R, Caratto M, Barbruni G, Fornaro F, Salerno A, Giovinazzo D, Sticchi C, Caratto E. Surgical and medical treatment in patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis. J Dig Dis. 2015;16:558-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Reinisch W, Olson A, Johanns J, Travers S, Rachmilewitz D, Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2462-2476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2744] [Cited by in RCA: 2886] [Article Influence: 144.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 18. | Järnerot G, Hertervig E, Friis-Liby I, Blomquist L, Karlén P, Grännö C, Vilien M, Ström M, Danielsson A, Verbaan H. Infliximab as rescue therapy in severe to moderately severe ulcerative colitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1805-1811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 774] [Cited by in RCA: 768] [Article Influence: 38.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kohn A, Daperno M, Armuzzi A, Cappello M, Biancone L, Orlando A, Viscido A, Annese V, Riegler G, Meucci G. Infliximab in severe ulcerative colitis: short-term results of different infusion regimens and long-term follow-up. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:747-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chang KH, Burke JP, Coffey JC. Infliximab versus cyclosporine as rescue therapy in acute severe steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013;28:287-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Croft A, Walsh A, Doecke J, Cooley R, Howlett M, Radford-Smith G. Outcomes of salvage therapy for steroid-refractory acute severe ulcerative colitis: ciclosporin vs. infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:294-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Narula N, Marshall JK, Colombel JF, Leontiadis GI, Williams JG, Muqtadir Z, Reinisch W. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis: Infliximab or Cyclosporine as Rescue Therapy in Patients With Severe Ulcerative Colitis Refractory to Steroids. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:477-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chaparro M, Burgueño P, Iglesias E, Panés J, Muñoz F, Bastida G, Castro L, Jiménez C, Mendoza JL, Barreiro-de Acosta M. Infliximab salvage therapy after failure of ciclosporin in corticosteroid-refractory ulcerative colitis: a multicentre study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:275-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Narula N, Fine M, Colombel JF, Marshall JK, Reinisch W. Systematic Review: Sequential Rescue Therapy in Severe Ulcerative Colitis: Do the Benefits Outweigh the Risks? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1683-1694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Amiot A, Grimaud JC, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Filippi J, Pariente B, Roblin X, Buisson A, Stefanescu C, Trang-Poisson C, Altwegg R. Effectiveness and Safety of Vedolizumab Induction Therapy for Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;Epub aheaad of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Khan HM, Mehmood F, Khan N. Optimal management of steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2015;8:293-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bressler B, Marshall JK, Bernstein CN, Bitton A, Jones J, Leontiadis GI, Panaccione R, Steinhart AH, Tse F, Feagan B. Clinical practice guidelines for the medical management of nonhospitalized ulcerative colitis: the Toronto consensus. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:1035-1058.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chapman RW, Selby WS, Jewell DP. Controlled trial of intravenous metronidazole as an adjunct to corticosteroids in severe ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1986;27:1210-1212. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Nitzan O, Elias M, Peretz A, Saliba W. Role of antibiotics for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1078-1087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Khan KJ, Ullman TA, Ford AC, Abreu MT, Abadir A, Marshall JK, Talley NJ, Moayyedi P. Antibiotic therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:661-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Dignass A, Lindsay JO, Sturm A, Windsor A, Colombel JF, Allez M, D’Haens G, D’Hoore A, Mantzaris G, Novacek G. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 2: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:991-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 728] [Cited by in RCA: 702] [Article Influence: 54.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ho GT, Mowat C, Goddard CJ, Fennell JM, Shah NB, Prescott RJ, Satsangi J. Predicting the outcome of severe ulcerative colitis: development of a novel risk score to aid early selection of patients for second-line medical therapy or surgery. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:1079-1087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Travis SP, Farrant JM, Ricketts C, Nolan DJ, Mortensen NM, Kettlewell MG, Jewell DP. Predicting outcome in severe ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1996;38:905-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 502] [Cited by in RCA: 519] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Lindgren SC, Flood LM, Kilander AF, Löfberg R, Persson TB, Sjödahl RI. Early predictors of glucocorticosteroid treatment failure in severe and moderately severe attacks of ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:831-835. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Ananthakrishnan AN, McGinley EL, Binion DG, Saeian K. Simple score to identify colectomy risk in ulcerative colitis hospitalizations. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1532-1540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Markel TA, Lou DC, Pfefferkorn M, Scherer LR, West K, Rouse T, Engum S, Ladd A, Rescorla FJ, Billmire DF. Steroids and poor nutrition are associated with infectious wound complications in children undergoing first stage procedures for ulcerative colitis. Surgery. 2008;144:540-545; discussion 545-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Mor IJ, Vogel JD, da Luz Moreira A, Shen B, Hammel J, Remzi FH. Infliximab in ulcerative colitis is associated with an increased risk of postoperative complications after restorative proctocolectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:1202-1207; discussion 1202-1210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Roberts SE, Williams JG, Yeates D, Goldacre MJ. Mortality in patients with and without colectomy admitted to hospital for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: record linkage studies. BMJ. 2007;335:1033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Pellino G, Sciaudone G, Candilio G, Canonico S, Selvaggi F. Rectosigmoid stump washout as an alternative to permanent mucous fistula in patients undergoing subtotal colectomy for ulcerative colitis in emergency settings. BMC Surg. 2012;12 Suppl 1:S31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Brady RR, Collie MH, Ho GT, Bartolo DC, Wilson RG, Dunlop MG. Outcomes of the rectal remnant following colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10:144-150. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Fazio VW, Kiran RP, Remzi FH, Coffey JC, Heneghan HM, Kirat HT, Manilich E, Shen B, Martin ST. Ileal pouch anal anastomosis: analysis of outcome and quality of life in 3707 patients. Ann Surg. 2013;257:679-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 528] [Article Influence: 44.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Wong NY, Eu KW. A defunctioning ileostomy does not prevent clinical anastomotic leak after a low anterior resection: a prospective, comparative study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:2076-2079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Sagar PM, Taylor BA. Pelvic ileal reservoirs: the options. Br J Surg. 1994;81:325-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Shannon A, Eng K, Kay M, Blanchard S, Wyllie R, Mahajan L, Worley S, Lavery I, Fazio V. Long-term follow up of ileal pouch anal anastomosis in a large cohort of pediatric and young adult patients with ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51:1181-1186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Kirat HT, Remzi FH, Kiran RP, Fazio VW. Comparison of outcomes after hand-sewn versus stapled ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in 3,109 patients. Surgery. 2009;146:723-729; discussion 729-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Joo M, Odze RD. Rectal sparing and skip lesions in ulcerative colitis: a comparative study of endoscopic and histologic findings in patients who underwent proctocolectomy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:689-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 47. | Scoglio D, Ahmed Ali U, Fichera A. Surgical treatment of ulcerative colitis: ileorectal vs ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13211-13218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Bikhchandani J, Polites SF, Wagie AE, Habermann EB, Cima RR. National trends of 3- versus 2-stage restorative proctocolectomy for chronic ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:199-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Zittan E, Wong-Chong N, Ma GW, McLeod RS, Silverberg MS, Cohen Z. Modified Two-stage Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis Results in Lower Rate of Anastomotic Leak Compared with Traditional Two-stage Surgery for Ulcerative Colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:766-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Swenson BR, Hollenbeak CS, Poritz LS, Koltun WA. Modified two-stage ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: equivalent outcomes with less resource utilization. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:256-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Park KT, Tsai R, Perez F, Cipriano LE, Bass D, Garber AM. Cost-effectiveness of early colectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastamosis versus standard medical therapy in severe ulcerative colitis. Ann Surg. 2012;256:117-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Watanabe K, Funayama Y, Fukushima K, Shibata C, Takahashi K, Sasaki I. Hand-assisted laparoscopic vs. open subtotal colectomy for severe ulcerative colitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:640-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Messenger DE, Mihailovic D, MacRae HM, O’Connor BI, Victor JC, McLeod RS. Subtotal colectomy in severe ulcerative and Crohn’s colitis: what benefit does the laparoscopic approach confer? Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:1349-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Gu J, Stocchi L, Remzi FH, Kiran RP. Total abdominal colectomy for severe ulcerative colitis: does the laparoscopic approach really have benefit? Surg Endosc. 2014;28:617-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Meagher AP, Farouk R, Dozois RR, Kelly KA, Pemberton JH. J ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for chronic ulcerative colitis: complications and long-term outcome in 1310 patients. Br J Surg. 1998;85:800-803. [PubMed] |

| 56. | Dafnis G. Early and late surgical outcomes of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis within a defined population in Sweden. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:842-849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Nordenvall C, Myrelid P, Ekbom A, Bottai M, Smedby KE, Olén O, Nilsson PJ. Probability, rate and timing of reconstructive surgery following colectomy for inflammatory bowel disease in Sweden: a population-based cohort study. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:882-890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Murphy PB, Khot Z, Vogt KN, Ott M, Dubois L. Quality of Life After Total Proctocolectomy With Ileostomy or IPAA: A Systematic Review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2015;58:899-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |