Published online Mar 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i3.202

Peer-review started: December 17, 2015

First decision: January 4, 2016

Revised: January 17, 2016

Accepted: February 16, 2016

Article in press: February 17, 2016

Published online: March 27, 2016

Processing time: 95 Days and 20.2 Hours

Pancreatic cystic neoplasms have been increasingly recognized recently. Comprising about 16% of all resected pancreatic cystic neoplasms, serous cystic neoplasms are uncommon benign lesions that are usually asymptomatic and found incidentally. Despite overall low risk of malignancy, these pancreatic cysts still generate anxiety, leading to intensive medical investigations with considerable financial cost to health care systems. This review discusses the general background of serous cystic neoplasms, including epidemiology and clinical characteristics, and provides an updated overview of diagnostic approaches based on clinical features, relevant imaging studies and new findings that are being discovered pertaining to diagnostic evaluation. We also concisely discuss and propose management strategies for better quality of life.

Core tip: Pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCNs) have been more frequently recognized clinically in recent years and serous cystic neoplasms (SCNs) account for a large proportion of all PCN cases. Recent reviews have paid much attention to general aspects of PCNs and have discussed various subtypes of PCNs, but there is still a lack of comprehensive review exclusively focused on SCNs. This review attempts to provide a concise overview and outlook of pancreatic SCN and propose management strategies.

- Citation: Zhang XP, Yu ZX, Zhao YP, Dai MH. Current perspectives on pancreatic serous cystic neoplasms: Diagnosis, management and beyond. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(3): 202-211

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i3/202.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i3.202

Pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCNs) are increasingly being recognized incidentally with widespread use of advanced imaging techniques, including computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS). According to the most recent WHO classification[1], PCNs comprise serous cystic neoplasms (SCNs), mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs), intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) and solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPENs). SCNs account for nearly 16% of surgically resected PCNs and > 30% of all clinically diagnosed PCNs[2-4], hence, they have become of concern and have posed a challenge to primary care clinicians and general practitioners. Not surprisingly, SCNs harbor some already known epidemiological characteristics. SCNs largely affect women (approximately 75% of all cases), and the mean age of patients who underwent pancreatic surgery for SCNs was 56 years in Europe, 58 years in Asia and 62 years in the United States[5,6]. SCNs tend to be larger if they occur in male patients[4]. In contrast with other premalignant or malignant PCNs (MCNs, IPMNs and SPENs), SCNs are usually benign, and the malignant variant serous cystadenocarcinoma is rare. To date, only approximately 30 cases of serous cystadenocarcinoma are reported in the literature[7]. Therefore, correct diagnosis is needed to avoid unnecessary surgical interventions and exclude other malignancies.

Morphologically, SCNs can be divided into four subtypes: Microcystic, macrocystic or oligocystic (< 10% of cases), mixed form (micro-macrocystic) and a solid variant form[8]. SCNs may arise in any part of the pancreas and occasionally can spread throughout the organ. The majority of SCNs are the microcystic lesions, which occur predominantly in the body and tail of the pancreas, whereas the oligocystic lesions normally arise from the head of the pancreas[9,10]. When multiple lesions are identified, Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL)-disease-associated pancreatic cysts should be taken into consideration[11]. VHL disease is a genetic disease, driven by mutation of the VHL tumor suppressor gene located on chromosome 3, which leads to development of several tumors, primarily hemangioblastoma of the central nervous system, retinal hemangioblastoma, renal cell carcinoma, adrenal pheochromocytoma and pancreatic tumors, mainly represented by pancreatic endocrine tumors and cystic tumors[12]. It is reported that SCNs are involved in 2.7%-9.5% of patients with VHL disease[13].

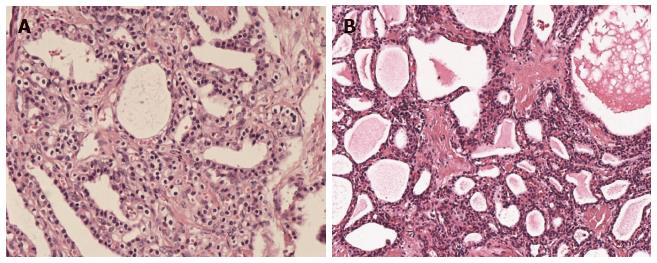

Histologically, SCN cystic walls are lined with cubic flat epithelia consisting of glycogen-rich, watery-fluid-producing cells[14] (Figure 1). The cytoplasm is either clear or eosinophilic and the nuclei are normally centrally located, small and hyperchromatic; mitoses are not commonly found[15]. Although some controversy still exists, it is widely accepted that SCNs originate from the centroanicar cells[16]. They normally express cytokeratins AE1/AE3, CAM 5.2, CK7, CK8, CK18 and CK19, epithelial membrane antigen, α-inhibin, and mucin 6[16,17].

According to a study led by Tseng et al[4], approximately 47% of patients with SCN were asymptomatic and diagnosed incidentally. As for symptoms, they are not specific and often attributed to mass effects or to infiltration of adjacent structures. Abdominal pain (25%), palpable mass (10%) and jaundice (7%) are the main clinical manifestations. It also has been shown that when lesions are > 4 cm, symptoms do occur more frequently if compared to lesions < 4 cm (72% vs 22%, P < 0.001)[4], which is in line with several studies reported elsewhere[18,19]. A more recent multinational study of 2622 cases of SCN revealed that patients could present with nonspecific abdominal pain (27%), pancreaticobiliary symptoms (9%), diabetes mellitus (5%), or other symptoms (4%), with the remaining patients being asymptomatic (61%)[20].

Given that SCNs are usually benign and asymptomatic, better surveillance and management strategies for these cysts call for accurate preoperative diagnosis. CT, MRI and EUS are three most commonly used imaging techniques for revealing SCNs. A recent study stated that the accuracy of preoperative diagnosis of PCN remains low, reaching approximately 60%, and in light of the exact diagnosis by pathology, surgical resection, most of which were Whipple resections, should not have been performed in approximately 8% of patients[21]. In another study cohort, 9% of PCN patients underwent pancreatic resection for a non-neoplastic condition[22], which further demonstrated the difficulty in differentiation between benign and premalignant lesions and that better preoperative diagnosis is urgently needed. Pancreatic cysts are readily identified in up to 20% of MRI studies, and 3% of CT scans[23,24]. Both CT and MRI predict the presence of malignancy in pancreatic cysts with 73%-79% accuracy[25]. In addition to routine radiological studies, EUS has emerged as a useful tool because it provides high-resolution imaging of the pancreas through the lumen of the stomach or duodenum and helps obtain detailed information of the cystic lesions, such as wall, margins, internal structures and parenchyma[26,27]. In a recent prospective cross-sectional study of the prevalence of incidental pancreatic cysts during routine outpatient EUS, the prevalence of incidental pancreatic cyst was 9.4% and most were < 1 cm[28]. The accuracy of EUS to differentiate benign from malignant neoplastic tumors and from non-neoplastic cysts remains debatable. Some studies have stated an accuracy of > 90%, while others have expressed doubt, especially when there is a lack of evidence of a solid mass or invasive tumor[29-31]. Despite this debate, another major advantage of EUS is its ability to collect fluid from cystic lesions via fine-needle aspiration (FNA) for cytological and biochemical analysis, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), amylase, and KRAS mutations[32].

Compared to other cystic neoplasms, accurate preoperative diagnosis of SCNs seems more feasible. As mentioned before, SCNs can be divided into four subtypes: Microcystic, macrocystic or oligocystic (< 10% of cases), mixed form (micro-macrocystic) and solid variant form[8]. VHL-disease-associated pancreatic cysts should be considered when other cystic lesions exist. A Japanese multicenter study of 172 SCNs diagnosed by resection and typical imaging findings noted highest diagnostic accuracy for microcystic SCN (85%), with lower diagnostic rates (17%-50%) for macrocystic and mixed types. CT alone is approximately 23% accurate at diagnosing SCN[33]. Diffusion-weighted MRI has proved to be a powerful tool with 100% sensitivity and 97% specificity for differentiating mucinous cysts from SCNs[34]. The pathognomonic central scar, which is formed by central coalescence of the septa and commonly contains foci of calcification on imaging, is present in only approximately 30% of these cysts[35].

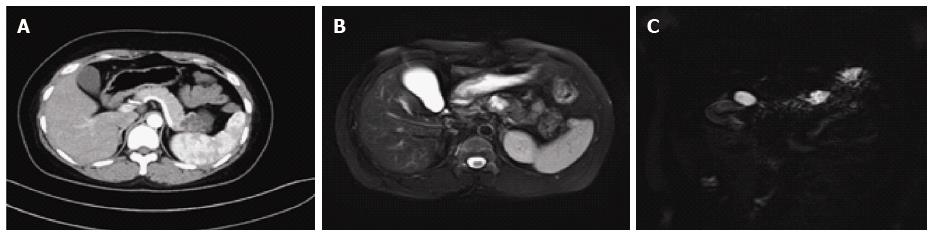

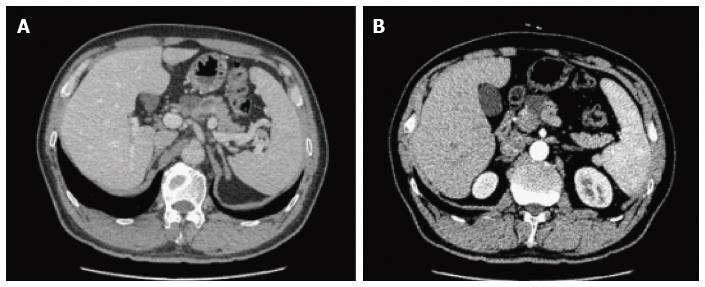

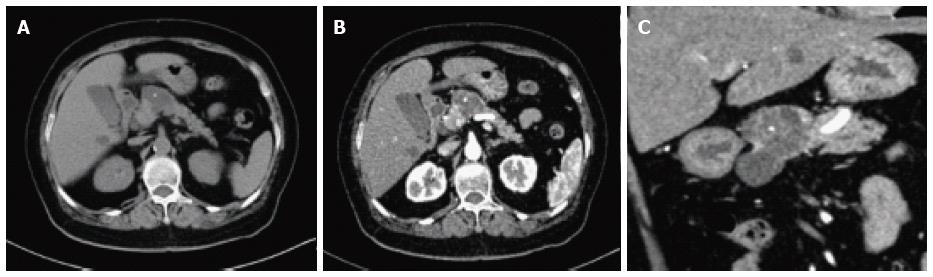

On CT/MRI, microcystic SCN typically appears as an isolated, lobulated, well-marginated, multilocular lesion, comprising a cluster of multiple (usually > 6) small cysts separated by a thin septum[26,36] (Figure 2). Each of the small cysts is usually < 2 cm[37]. Occasionally, the “honeycomb” pattern, characterized by numerous, sub-centimeter cysts appears as a solid mass on CT (Figure 3), but has high signal intensity when T2-weighted MRI is applied[37]. Macrocystic SCN is characterized by a limited number of cysts, usually < 6, showing a diameter > 2 cm, or even one single cyst[38] (Figure 4). This subtype can be seen in approximately 10% of all cases of SCN but poses difficulty for differentiating it from MCN and branch-duct (BD)-IPMN, based on the findings of CT or MRI[39]. In addition, if a patient has a reported history of pancreatitis, pseudocyst should be considered[40]. The mixed micro-macrocystic type is depicted as a combination of the above two types of lesions. As for the solid variant, it consists of small cysts separated by multiple, thick fibrous septa[41]. VHL-disease-associated pancreatic cysts, which can occur in 50%-80% of the patients with VHL disease, and are occasionally misdiagnosed as macrocystic SCNs, tend to form multiple lesions and are even diffuse throughout the pancreas[42,43].

Generally, microcystic SCNs on EUS are imaged as numerous (> 6) small (< 1-2 cm) fluid-filled cysts with thin-walled septa and possibly calcification of the central septum[44,45] (Figure 5). The honeycomb variants are interspersed within dense fibrous septa, with or without central fibrosis or calcification[46,47]. The less common oligocystic SCNs usually contain larger (> 2 cm) cysts[48]. However, the solid variant, which is defined when lesions are predominantly solid (< 10% cystic portion) and might resemble a ductal carcinoma on CT, contains numerous tiny cysts (1-2 mm) and appears as a hypoechoic mass on EUS[49].

Management and surveillance of SCNs depend on correct preoperative diagnosis. One major concern is potential misdiagnosis of a malignancy or premalignancy as a benign SCN, which was more frequent in the past; it was reported in seven of 28 patients in one study and in two of 49 patients in another[50,51]. Among SCNs, macrocystic SCNs are frequently undistinguishable from MCNs and BD-IPMNs. BD-IPMNs may also present in a polycystic pattern, similar to microcystic SCNs[52]. Typically, unlike IPMNs, SCNs are characterized by lack of communication with the main pancreatic duct. However, the absence of communication does not allow for the exclusion of IPMN, although this absence may favor the diagnosis of MCN over SCN[53,54]. In contrast to MCNs, which usually exhibit a smooth oval shape and varied signal intensity (depending on the fluid viscosity of each lobule), macrocystic SCNs typically present with a thin wall and lobulated contours and can be found in the head of the pancreas[55]. A central calcified scar is virtually pathognomonic for SCNs (Figure 6), whereas peripheral calcifications are frequently observed in MCNs[56]. Many solid variant SCNs show arterial hypervascularity on imaging studies and are frequently misdiagnosed as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (pNETs)[57-59]. A recent study found that the frequency of hypervascular solid-appearing SCNs was 7.3% among surgically confirmed SCNs and unenhanced CT and MR features can help to differentiate solid variant SCNs from pNETs[60].

Despite various potential complications of EUS-FNA, such as bleeding caused by injury of the subepithelial vascular plexus of SCNs, pancreatitis, infection, and even the seeding of malignant cells along the tract of the needle have been suggested[61-63], EUS-FNA-related morbidity and mortality rates have remained low[64] and the widespread use of EUS-FNA has yielded a wealth of information for cytological, chemical and molecular analysis of SCNs.

A 22- or 25-gauge needle is often used when aspirating cyst fluid during EUS-FNA. SCNs usually contain little fluid and the fluid usually contains few cellular components, and FNA cytological analysis has an unreliable sensitivity of only 30%-40%[65]. For chemical analysis, assessment of tumor markers such as CEA, carbohydrate antigen (CA)19-9, CA15-3, CA72-4, and enzymes like amylase and lipase is often carried out, although it has proved of limited diagnostic value[66]. Fluid from SCNs universally has low CEA levels. A level < 5 ng/mL is 95% specific for SCN, pseudocyst or pNET[67]. However, an elevated CEA level favors a mucinous lesion, although the exact cut-off level is still in debate. It is also important to mention that the CEA threshold varies in different centers, ranging from 5 ng/mL to > 100 ng/mL[68]. When a classic CEA cut-off level of 192 ng/mL is applied, it yields 73% sensitivity and 84% specificity for mucinous cysts[69]. An amylase level < 250 U/L favors diagnosis of SCN over pseudocyst, with a sensitivity of 44%, specificity of 98% and overall accuracy of 65%[68]. Other than CEA and amylase, recent studies have revealed that levels of cystic fluid metabolites glucose and kynurenine are markedly elevated in SCNs compared to MCNs, which aids the diagnosis of SCNs[70,71]. Although large prospective studies are warranted to validate these promising results, they shed light on a new path to seek better biomarkers. Molecular analysis of cystic fluid has gained in interest in recent years, in parallel with the advent of new techniques on sequencing. DNA analysis of KRAS mutations may help identify mucinous cysts with 54% sensitivity and 100% specificity, as demonstrated in a study containing 142 surgically resected cysts. When CEA and KRAS analysis were collectively applied, the sensitivity climbed to 83% while the specificity dropped to 85%[72]. More interestingly, data from whole-exome sequencing of PCNs revealed that the application of a panel of five genes (VHL, RNF43, KRAS, GNAS and CTNNB1) allowed correct distinction of mucinous from nonmucinous cysts. All eight SCNs had intragenic mutations of VHL or loss of heterozygosity in or adjacent to VHL and did not contain mutations of the other four genes. Furthermore, point mutations of VHL gene were detected in cystic fluid analysis in half of the SCNs. Nevertheless, IPMNs had alterations of RNF43, GNAS or KRAS and never had VHL or CTNNB1 mutations. MCNs always harbored KRAS or RNF43 mutations but never contained GNAS, CTNNB1 or VHL mutations[73]. Another study stated that GNAS mutations were present in 10% of their cases of SCN, which was still significantly lower than in IPMNs[74]. Thereafter, the identification of GNAS mutation may help discrimination of SCN from IPMN. Another mainstay of research of cystic molecular analysis gives insights into miRNAs. A panel of four miRNAs comprised miR-31-5p, miR-483-5p, miR-99a-5p and miR-375 has been developed to differentiate SCNs accurately from mucinous lesions, with 90% sensitivity and 100% specificity[75]. While promising, these results were based on surgically archived specimens but not on cystic fluid, therefore, validation in cystic fluid samples should be addressed in future studies to fit these findings better in preoperative scenarios.

As mentioned before, most SCNs follow a benign course and malignant SCNs (serous cystadenocarcinoma) are rare (< 1% of all cases). According to an investigation of 193 SCNs, along with a literature review, the clinicopathological characteristics of solid and macrocystic SCN variants are similar to those of their microcystic counterpart, and there are no deaths that are directly attributable to dissemination/malignant behavior of SCNs[76]. It is also recommended to consider and manage SCNs as benign neoplasms initially[77]. For this reason, correct preoperative diagnosis of SCNs could spare many unnecessary interventions and guide optimal management strategies. Currently, there is no universal consensus on the best management strategy, but it is widely accepted that not every single case should be surgically resected, regardless of how advanced surgical technology has been developed, and symptomatic, local invasive or potential malignant SCNs should be resected[37,54,78]. It is also advised that resection should be considered for large (> 4 cm), rapidly growing SCNs, given that such SCNs are more likely to cause symptoms[4,33]. However, it is difficult for a clinician to predict whether and when an incidentally found asymptomatic SCN will grow to cause symptoms. One older study claimed that a more rapid growth rate of approximately 1.98 cm/year was observed in cysts > 4 cm, whereas the growth rate was approximately 0.12 cm/year in cysts < 4 cm[4]. A more recent multicenter study failed to confirm those results. In that same study, a rate of growth of 6.2% per year or a doubling time of 12 years was calculated for the nonresected SCNs, while resected SCNs grew faster (17% per year for a doubling time of 4.5 years)[18]. In addition, there is also a paucity of knowledge about the relationship between growth rate and potential malignancy[7]. Obviously, symptoms do occur when fast-growing SCNs are left unresected[79]. It is tempting to conclude that initial size is neither associated with malignant transformation, nor proportionally related to developing symptoms. However, growth rate is more powerful to predict if and when the symptoms occur. Thus, the growth rate should be weighed when considering if an SCN should be subjected to surgical intervention. One multinational study stated that, in patients followed beyond 1 year (n = 1271), size increased in 37% (growth rate: 4 mm/year), was stable in 57%, and decreased in 6%, hence, surgical treatment should be proposed only in cases in which diagnosis remains uncertain after complete work-up[20].

Surgery is considered curative. Despite increasing experience and advanced surgical techniques, pancreatic surgery holds a perioperative morbidity of 15%-30% and a mortality rate of 1%-2%, even in high-volume centers[3]. The indications for surgical intervention are as follows: (1) presence of symptoms; (2) Uncertain diagnosis. MCNs and IPMNs can mimic SCNs on radiology scans, especially macrocytic SCNs. When premalignant MCNs and IPMNs cannot be excluded, the lesions can be managed as IPMNs when the cysts are < 4 cm[80] and are advised to be surgically removed accordingly following the International consensus in 2012 and the European consensus in 2013[81,82]; and (3) growth rate of the neoplasm. As discussed above, large SCNs are not correlated with an increased risk of malignancy. Also, growth rate is not linked with initial size. The notion that any cyst > 4 cm or even > 5 cm be resected should be abandoned. In this regard, clinicians need to remain cautious when neoplasms grow rapidly, and make decisions on a case-by-case basis, including patient’s age, comorbidity and tumor location. Large SCNs can always be closely observed first and then sent for surgery once they grow faster and cause unrelieved symptoms.

From an anatomical point of view, surgical resection of an SCN largely depends on the location of the lesion. As a result of the benign nature of SCN, as a general rule, it is recommended that pancreatic functions are protected and preserved as much as possible for better outcome and quality of life. If SCNs are localized in the pancreatic head, pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy or Begar procedure is often carried out. If SCNs are located in the body or tail of the pancreas, spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy should be the first choice. For patients whose SCNs are located in the neck of the pancreas, central segmental pancreatectomy is an alternative procedure, preserving islet cell mass and reducing the risk of iatrogenic insulin-dependent diabetes. Enucleation is not recommended because greater morbidity (up to 35%) and associated complications such as pancreatic fistula[83] have been reported.

As mentioned above, clinicians are encouraged to manage SCNs in a conservative manner, which means that, initially, these lesions do not require surgery but serial follow-up when radiological diagnosis is certain and symptoms are absent. However, to date, the best follow-up strategy has not been standardized. Some advocate follow-up imaging every 12 mo, while others suggest biennial surveillance[84,85]. The European consensus in 2013 suggests that asymptomatic nonresected patients should enter a follow-up program, initially repeated after 3-6 mo, and then individualized depending on growth rate[81]. Once SCNs are resected, no further surveillance imaging is needed.

Comprising about 16% of all resected PCNs, SCNs are uncommon benign lesions that are asymptomatic and found incidentally. Despite overall low risk of malignancy, the presence of these pancreatic cysts still generates anxiety, leading to extensive medical investigation with considerable financial cost to health care systems. CT and MRI alone are not powerful enough to characterize cystic pancreatic lesions fully, and more specifically, to differentiate macrocystic SCNs from MCNs. However, EUS, with or without addition of FNA, adds more diagnostic value to conventional imaging techniques. CEA, although not perfect, plays a role in differentiating pancreatic cystic lesions. New cystic fluid markers from chemical and molecular analyses are just beginning to emerge, paving a new way to future research. As for treatment and management strategy, surgery should be limited only to symptomatic SCNs and lesions that show aggressive behavior, while the majority of patients should be strictly monitored and followed up by serial imaging. Further investigations on best follow-up strategy are warranted. Patients would benefit from multidisciplinary management and receive precise medical advice once gastroenterology, surgery, pathology and radiology are all involved in individual patient care as a team. As such, patient care based on a multidisciplinary team is encouraged if applicable.

We would like to thank Ya-Tong Li for draft proofreading. All images in this review were provided by Department of Radiology & Department of Pathology, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, China.

P- Reviewer: Beltran MA, Kleeff J, Talukdar R S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press 2010; 48-58. |

| 2. | Compagno J, Oertel JE. Microcystic adenomas of the pancreas (glycogen-rich cystadenomas): a clinicopathologic study of 34 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1978;69:289-298. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Galanis C, Zamani A, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, Lillemoe KD, Caparrelli D, Chang D, Hruban RH, Yeo CJ. Resected serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: a review of 158 patients with recommendations for treatment. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:820-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tseng JF, Warshaw AL, Sahani DV, Lauwers GY, Rattner DW, Fernandez-del Castillo C. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: tumor growth rates and recommendations for treatment. Ann Surg. 2005;242:413-419; discussion 419-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bassi C, Salvia R, Molinari E, Biasutti C, Falconi M, Pederzoli P. Management of 100 consecutive cases of pancreatic serous cystadenoma: wait for symptoms and see at imaging or vice versa? World J Surg. 2003;27:319-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Le Borgne J, de Calan L, Partensky C. Cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas of the pancreas: a multiinstitutional retrospective study of 398 cases. French Surgical Association. Ann Surg. 1999;230:152-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Strobel O, Z’graggen K, Schmitz-Winnenthal FH, Friess H, Kappeler A, Zimmermann A, Uhl W, Büchler MW. Risk of malignancy in serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Digestion. 2003;68:24-33. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Roggin KK, Chennat J, Oto A, Noffsinger A, Briggs A, Matthews JB. Pancreatic cystic neoplasm. Curr Probl Surg. 2010;47:459-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chatelain D, Hammel P, O’Toole D, Terris B, Vilgrain V, Palazzo L, Belghiti J, Lévy P, Ruszniewski P, Fléjou JF. Macrocystic form of serous pancreatic cystadenoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2566-2571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sperti C, Pasquali C, Perasole A, Liessi G, Pedrazzoli S. Macrocystic serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: clinicopathologic features in seven cases. Int J Pancreatol. 2000;28:1-7. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Tanno S, Obara T, Sohma M, Tanaka T, Izawa T, Fujii T, Nishino N, Ura H, Kohgo Y. Multifocal serous cystadenoma of the pancreas. A case report and review of the literature. Int J Pancreatol. 1998;24:129-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Walther M, Chew EY, Libutti SK, Linehan WM, Oldfield EH. von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet. 2003;361:2059-2067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1083] [Cited by in RCA: 1012] [Article Influence: 46.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Girelli R, Bassi C, Falconi M, De Santis L, Bonora A, Caldiron E, Sartori N, Salvia R, Briani G, Pederzoli P. Pancreatic cystic manifestations in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Int J Pancreatol. 1997;22:101-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Belsley NA, Pitman MB, Lauwers GY, Brugge WR, Deshpande V. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: limitations and pitfalls of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Cancer. 2008;114:102-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Salvia R, Crippa S, Partelli S, Malleo G, Marcheggiani G, Bacchion M, Butturini G, Bassi C. Pancreatic cystic tumours: when to resect, when to observe. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2010;14:395-406. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Buisine MP, Devisme L, Degand P, Dieu MC, Gosselin B, Copin MC, Aubert JP, Porchet N. Developmental mucin gene expression in the gastroduodenal tract and accessory digestive glands. II. Duodenum and liver, gallbladder, and pancreas. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:1667-1676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kosmahl M, Wagner J, Peters K, Sipos B, Klöppel G. Serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: an immunohistochemical analysis revealing alpha-inhibin, neuron-specific enolase, and MUC6 as new markers. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:339-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | El-Hayek KM, Brown N, O’Rourke C, Falk G, Morris-Stiff G, Walsh RM. Rate of growth of pancreatic serous cystadenoma as an indication for resection. Surgery. 2013;154:794-800; discussion 800-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fukasawa M, Maguchi H, Takahashi K, Katanuma A, Osanai M, Kurita A, Ichiya T, Tsuchiya T, Kin T. Clinical features and natural history of serous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2010;10:695-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jais B, Rebours V, Malleo G, Salvia R, Fontana M, Maggino L, Bassi C, Manfredi R, Moran R, Lennon AM. Serous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas: a multinational study of 2622 patients under the auspices of the International Association of Pancreatology and European Pancreatic Club (European Study Group on Cystic Tumors of the Pancreas). Gut. 2016;65:305-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Del Chiaro M, Segersvärd R, Pozzi Mucelli R, Rangelova E, Kartalis N, Ansorge C, Arnelo U, Blomberg J, Löhr M, Verbeke C. Comparison of preoperative conference-based diagnosis with histology of cystic tumors of the pancreas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1539-1544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Salvia R, Malleo G, Marchegiani G, Pennacchio S, Paiella S, Paini M, Pea A, Butturini G, Pederzoli P, Bassi C. Pancreatic resections for cystic neoplasms: from the surgeon’s presumption to the pathologist’s reality. Surgery. 2012;152:S135-S142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Laffan TA, Horton KM, Klein AP, Berlanstein B, Siegelman SS, Kawamoto S, Johnson PT, Fishman EK, Hruban RH. Prevalence of unsuspected pancreatic cysts on MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:802-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 724] [Cited by in RCA: 658] [Article Influence: 38.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lee KS, Sekhar A, Rofsky NM, Pedrosa I. Prevalence of incidental pancreatic cysts in the adult population on MR imaging. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2079-2084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 420] [Cited by in RCA: 436] [Article Influence: 29.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kim YC, Choi JY, Chung YE, Bang S, Kim MJ, Park MS, Kim KW. Comparison of MRI and endoscopic ultrasound in the characterization of pancreatic cystic lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:947-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sahani DV, Kadavigere R, Saokar A, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Brugge WR, Hahn PF. Cystic pancreatic lesions: a simple imaging-based classification system for guiding management. Radiographics. 2005;25:1471-1484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Khashab MA, Kim K, Lennon AM, Shin EJ, Tignor AS, Amateau SK, Singh VK, Wolfgang CL, Hruban RH, Canto MI. Should we do EUS/FNA on patients with pancreatic cysts? The incremental diagnostic yield of EUS over CT/MRI for prediction of cystic neoplasms. Pancreas. 2013;42:717-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sey MS, Teagarden S, Settles D, McGreevy K, Coté GA, Sherman S, McHenry L, LeBlanc JK, Al-Haddad M, DeWitt JM. Prospective Cross-Sectional Study of the Prevalence of Incidental Pancreatic Cysts During Routine Outpatient Endoscopic Ultrasound. Pancreas. 2015;44:1130-1133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ahmad NA, Kochman ML, Lewis JD, Ginsberg GG. Can EUS alone differentiate between malignant and benign cystic lesions of the pancreas? Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3295-3300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Brugge WR. The role of EUS in the diagnosis of cystic lesions of the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:S18-S22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Papanikolaou IS, Adler A, Neumann U, Neuhaus P, Rösch T. Endoscopic ultrasound in pancreatic disease--its influence on surgical decision-making. An update 2008. Pancreatology. 2009;9:55-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lee LS, Saltzman JR, Bounds BC, Poneros JM, Brugge WR, Thompson CC. EUS-guided fine needle aspiration of pancreatic cysts: a retrospective analysis of complications and their predictors. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:231-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Khashab MA, Shin EJ, Amateau S, Canto MI, Hruban RH, Fishman EK, Cameron JL, Edil BH, Wolfgang CL, Schulick RD. Tumor size and location correlate with behavior of pancreatic serous cystic neoplasms. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1521-1526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Schraibman V, Goldman SM, Ardengh JC, Goldenberg A, Lobo E, Linhares MM, Gonzales AM, Abdala N, Abud TG, Ajzen SA. New trends in diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging as a tool in differentiation of serous cystadenoma and mucinous cystic tumor: a prospective study. Pancreatology. 2011;11:43-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Shah AA, Sainani NI, Kambadakone AR, Shah ZK, Deshpande V, Hahn PF, Sahani DV. Predictive value of multi-detector computed tomography for accurate diagnosis of serous cystadenoma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2739-2747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Macari M, Finn ME, Bennett GL, Cho KC, Newman E, Hajdu CH, Babb JS. Differentiating pancreatic cystic neoplasms from pancreatic pseudocysts at MR imaging: value of perceived internal debris. Radiology. 2009;251:77-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sakorafas GH, Smyrniotis V, Reid-Lombardo KM, Sarr MG. Primary pancreatic cystic neoplasms revisited. Part I: serous cystic neoplasms. Surg Oncol. 2011;20:e84-e92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Khurana B, Mortelé KJ, Glickman J, Silverman SG, Ros PR. Macrocystic serous adenoma of the pancreas: radiologic-pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:119-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kim SY, Lee JM, Kim SH, Shin KS, Kim YJ, An SK, Han CJ, Han JK, Choi BI. Macrocystic neoplasms of the pancreas: CT differentiation of serous oligocystic adenoma from mucinous cystadenoma and intraductal papillary mucinous tumor. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:1192-1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Cohen-Scali F, Vilgrain V, Brancatelli G, Hammel P, Vullierme MP, Sauvanet A, Menu Y. Discrimination of unilocular macrocystic serous cystadenoma from pancreatic pseudocyst and mucinous cystadenoma with CT: initial observations. Radiology. 2003;228:727-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Hol L, Signoretti M, Poley JW. Management of pancreatic cysts: a review of the current guidelines. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2015;61:87-99. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Hammel PR, Vilgrain V, Terris B, Penfornis A, Sauvanet A, Correas JM, Chauveau D, Balian A, Beigelman C, O’Toole D. Pancreatic involvement in von Hippel-Lindau disease. The Groupe Francophone d’Etude de la Maladie de von Hippel-Lindau. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1087-1095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Mohr VH, Vortmeyer AO, Zhuang Z, Libutti SK, Walther MM, Choyke PL, Zbar B, Linehan WM, Lubensky IA. Histopathology and molecular genetics of multiple cysts and microcystic (serous) adenomas of the pancreas in von Hippel-Lindau patients. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:1615-1621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Michael H, Gress F. Diagnosis of cystic neoplasms with endoscopic ultrasound. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12:719-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Brugge WR. Role of endoscopic ultrasound in the diagnosis of cystic lesions of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2001;1:637-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Mathieu D, Guigui B, Valette PJ, Dao TH, Bruneton JN, Bruel JM, Pringot J, Vasile N. Pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Radiol Clin North Am. 1989;27:163-176. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Warshaw AL, Compton CC, Lewandrowski K, Cardenosa G, Mueller PR. Cystic tumors of the pancreas. New clinical, radiologic, and pathologic observations in 67 patients. Ann Surg. 1990;212:432-443; discussion 444-445. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Gouhiri M, Soyer P, Barbagelatta M, Rymer R. Macrocystic serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: CT and endosonographic features. Abdom Imaging. 1999;24:72-74. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Sun HY, Kim SH, Kim MA, Lee JY, Han JK, Choi BI. CT imaging spectrum of pancreatic serous tumors: based on new pathologic classification. Eur J Radiol. 2010;75:e45-e55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Curry CA, Eng J, Horton KM, Urban B, Siegelman S, Kuszyk BS, Fishman EK. CT of primary cystic pancreatic neoplasms: can CT be used for patient triage and treatment? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:99-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Procacci C, Biasiutti C, Carbognin G, Accordini S, Bicego E, Guarise A, Spoto E, Andreis IA, De Marco R, Megibow AJ. Characterization of cystic tumors of the pancreas: CT accuracy. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1999;23:906-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Di Cataldo A, Palmucci S, Latino R, Trombatore C, Cappello G, Amico A, La Greca G, Petrillo G. Cystic pancreatic tumors: should we resect all of them? Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2014;18:16-23. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Taouli B, Vilgrain V, O’Toole D, Vullierme MP, Terris B, Menu Y. Intraductal papillary mucinous tumors of the pancreas: features with multimodality imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002;26:223-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Farrell JJ. Prevalence, Diagnosis and Management of Pancreatic Cystic Neoplasms: Current Status and Future Directions. Gut Liver. 2015;9:571-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Goh BK, Tan YM, Yap WM, Cheow PC, Chow PK, Chung YF, Wong WK, Ooi LL. Pancreatic serous oligocystic adenomas: clinicopathologic features and a comparison with serous microcystic adenomas and mucinous cystic neoplasms. World J Surg. 2006;30:1553-1559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Choi JY, Kim MJ, Lee JY, Lim JS, Chung JJ, Kim KW, Yoo HS. Typical and atypical manifestations of serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: imaging findings with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:136-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Yamaguchi M. Solid serous adenoma of the pancreas: a solid variant of serous cystadenoma or a separate disease entity? J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:178-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Yasuda A, Sawai H, Ochi N, Matsuo Y, Okada Y, Takeyama H. Solid variant of serous cystadenoma of the pancreas. Arch Med Sci. 2011;7:353-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Hayashi K, Fujimitsu R, Ida M, Sakamoto K, Higashihara H, Hamada Y, Yoshimitsu K. CT differentiation of solid serous cystadenoma vs endocrine tumor of the pancreas. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:e203-e208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Park HS, Kim SY, Hong SM, Park SH, Lee SS, Byun JH, Kim JH, Kim HJ, Lee MG. Hypervascular solid-appearing serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas: Differential diagnosis with neuroendocrine tumours. Eur Radiol. 2015;Sep 2; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Fasanella KE, McGrath K. Cystic lesions and intraductal neoplasms of the pancreas. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;23:35-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | O’Toole D, Palazzo L, Arotçarena R, Dancour A, Aubert A, Hammel P, Amaris J, Ruszniewski P. Assessment of complications of EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:470-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Varadarajulu S, Eloubeidi MA. Frequency and significance of acute intracystic hemorrhage during EUS-FNA of cystic lesions of the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:631-635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Wang KX, Ben QW, Jin ZD, Du YQ, Zou DW, Liao Z, Li ZS. Assessment of morbidity and mortality associated with EUS-guided FNA: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:283-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 329] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Frossard JL, Amouyal P, Amouyal G, Palazzo L, Amaris J, Soldan M, Giostra E, Spahr L, Hadengue A, Fabre M. Performance of endosonography-guided fine needle aspiration and biopsy in the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1516-1524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Lee LS. Incidental Cystic Lesions in the Pancreas: Resect? EUS? Follow? Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2014;12:333-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Khalid A, Brugge W. ACG practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2339-2349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | van der Waaij LA, van Dullemen HM, Porte RJ. Cyst fluid analysis in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions: a pooled analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:383-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 456] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Brugge WR, Lewandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrowski E, Centeno BA, Szydlo T, Regan S, del Castillo CF, Warshaw AL. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1330-1336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1016] [Cited by in RCA: 901] [Article Influence: 42.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Park WG, Wu M, Bowen R, Zheng M, Fitch WL, Pai RK, Wodziak D, Visser BC, Poultsides GA, Norton JA. Metabolomic-derived novel cyst fluid biomarkers for pancreatic cysts: glucose and kynurenine. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:295-302.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Zikos T, Pham K, Bowen R, Chen AM, Banerjee S, Friedland S, Dua MM, Norton JA, Poultsides GA, Visser BC. Cyst Fluid Glucose is Rapidly Feasible and Accurate in Diagnosing Mucinous Pancreatic Cysts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:909-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Nikiforova MN, Khalid A, Fasanella KE, McGrath KM, Brand RE, Chennat JS, Slivka A, Zeh HJ, Zureikat AH, Krasinskas AM. Integration of KRAS testing in the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions: a clinical experience of 618 pancreatic cysts. Mod Pathol. 2013;26:1478-1487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Wu J, Jiao Y, Dal Molin M, Maitra A, de Wilde RF, Wood LD, Eshleman JR, Goggins MG, Wolfgang CL, Canto MI. Whole-exome sequencing of neoplastic cysts of the pancreas reveals recurrent mutations in components of ubiquitin-dependent pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:21188-21193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 551] [Cited by in RCA: 482] [Article Influence: 34.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Lee LS, Doyle LA, Houghton J, Sah S, Bellizzi AM, Szafranska-Schwarzbach AE, Conner JR, Kadiyala V, Suleiman SL, Banks PA. Differential expression of GNAS and KRAS mutations in pancreatic cysts. JOP. 2014;15:581-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Lee LS, Szafranska-Schwarzbach AE, Wylie D, Doyle LA, Bellizzi AM, Kadiyala V, Suleiman S, Banks PA, Andruss BF, Conwell DL. Investigating MicroRNA Expression Profiles in Pancreatic Cystic Neoplasms. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2014;5:e47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Reid MD, Choi HJ, Memis B, Krasinskas AM, Jang KT, Akkas G, Maithel SK, Sarmiento JM, Kooby DA, Basturk O. Serous Neoplasms of the Pancreas: A Clinicopathologic Analysis of 193 Cases and Literature Review With New Insights on Macrocystic and Solid Variants and Critical Reappraisal of So-called “Serous Cystadenocarcinoma”. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:1597-1610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Sakorafas GH, Sarr MG. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas; what a clinician should know. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:507-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Antonini F, Fuccio L, Fabbri C, Macarri G, Palazzo L. Management of serous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9:115-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Garcea G, Ong SL, Rajesh A, Neal CP, Pollard CA, Berry DP, Dennison AR. Cystic lesions of the pancreas. A diagnostic and management dilemma. Pancreatology. 2008;8:236-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Crippa S, Salvia R, Warshaw AL, Domínguez I, Bassi C, Falconi M, Thayer SP, Zamboni G, Lauwers GY, Mino-Kenudson M. Mucinous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas is not an aggressive entity: lessons from 163 resected patients. Ann Surg. 2008;247:571-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 340] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Del Chiaro M, Verbeke C, Salvia R, Klöppel G, Werner J, McKay C, Friess H, Manfredi R, Van Cutsem E, Löhr M. European experts consensus statement on cystic tumours of the pancreas. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:703-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Tanaka M, Fernández-del Castillo C, Adsay V, Chari S, Falconi M, Jang JY, Kimura W, Levy P, Pitman MB, Schmidt CM. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12:183-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1714] [Cited by in RCA: 1614] [Article Influence: 124.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Pyke CM, van Heerden JA, Colby TV, Sarr MG, Weaver AL. The spectrum of serous cystadenoma of the pancreas. Clinical, pathologic, and surgical aspects. Ann Surg. 1992;215:132-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Wargo JA, Fernandez-del-Castillo C, Warshaw AL. Management of pancreatic serous cystadenomas. Adv Surg. 2009;43:23-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Tseng JF. Management of serous cystadenoma of the pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:408-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |