Published online May 27, 2015. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v7.i5.71

Peer-review started: January 2, 2015

First decision: January 20, 2015

Revised: March 2, 2015

Accepted: April 10, 2015

Article in press: April 14, 2015

Published online: May 27, 2015

Processing time: 138 Days and 17.6 Hours

AIM: To evaluate whether lymph node pick up by separate stations could be an indicator of patients submitted to appropriate surgical treatment.

METHODS: One thousand two hundred and three consecutive gastric cancer patients submitted to radical resection in 7 general hospitals and for whom no information was available on the extension of lymphatic dissection were included in this retrospective study.

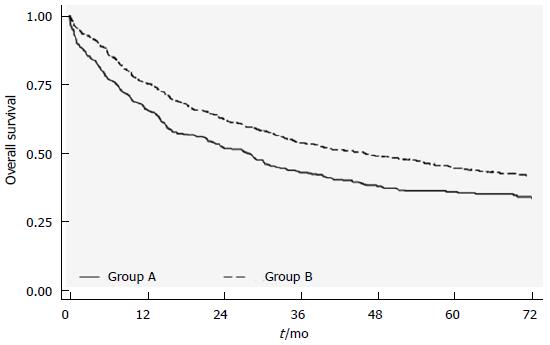

RESULTS: Patients were divided into 2 groups: group A, where the stomach specimen was directly formalin-fixed and sent to the pathologist, and group B, where lymph nodes were picked up after surgery and fixed for separate stations. Sixty-two point three percent of group A patients showed < 16 retrieved lymph nodes compared to 19.4% of group B (P < 0.0001). Group B (separate stations) patients had significantly higher survival rates than those in group A [46.1 mo (95%CI: 36.5-56.0) vs 27.7 mo (95%CI: 21.3-31.9); P = 0.0001], independently of T or N stage. In multivariate analysis, group A also showed a higher risk of death than group B (HR = 1.24; 95%CI: 1.05-1.46).

CONCLUSION: Separate lymphatic station dissection increases the number of retrieved nodes, leads to better tumor staging, and permits verification of the surgical dissection. The number of dissected stations could potentially be used as an index to evaluate the quality of treatment received.

Core tip: Lymph node retrieval in the operating theater after surgical resection is a common practice in Eastern Asia. When applied in the west, the procedure permits a higher number of lymph nodes to be detected, thus improving tumor staging. In the present multicenter study in which the participating centers used different surgical procedures, patients who were submitted to accurate lymph node pick up showed better survival than those were not. Although we are aware that this procedure cannot improve survival, we believe that it can identify patients submitted to a more accurate treatment.

- Citation: Morgagni P, Nanni O, Carretta E, Altini M, Saragoni L, Falcini F, Garcea D. Lymph node pick up by separate stations: Option or necessity? World J Gastrointest Surg 2015; 7(5): 71-77

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v7/i5/71.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v7.i5.71

Lymph node dissection has always been a subject of great debate. The extension of surgical lymphatic dissection[1], N stage definition in TNM or N ratio classifications[2-4], and the surgeon or pathologist’s role in lymph node pick up are widely discussed issues, especially when few lymph nodes are retrieved, as frequently occurs in Western countries. In fact, although a low number of detected lymph nodes may indicate a lack of accuracy by the pathologist, it may also reflect limited surgical lymphatic dissection.

The accuracy of lymph node retrieval has an important impact on staging, and the number of retrieved lymph nodes is generally reported in multicenter studies to underline the kind of lymphatic dissection performed[5,6]. Moreover, the number of positive lymph nodes is related to the overall number of dissected lymph nodes and is considered a significant prognostic factor[2,4,5,7-10].

The main aim of this study was to verify whether immediate pick up and collection of lymph nodes by separate stations in a fresh gastric cancer specimen can improve the number of lymph nodes retrieved. We also evaluated whether an increased number of separate lymphatic stations sent for histological examination can identify patients adequately treated from a surgical point of view. Such an approach leads to better staging and facilitates the choice of subsequent cancer treatments.

This retrospective study was carried out on 1203 consecutive gastric cancer patients radically resected during the period 2004-2008 in Area Vasta Romagna (AVR), a catchment area of 1100000 inhabitants with a high gastric cancer incidence compared to other Italian regions and western populations. Information on patients was retrieved from the hospital discharge records (HDR) of the seven main AVR hospitals. Patients were identified using the ICD-9 codes of the International Classification of Diseases. Focusing on a radical surgical approach, the sample was limited to patients with a primary diagnosis code of stomach cancer (151.x) and primary or secondary procedure codes of partial gastrectomy (43.6, 43.7, 43.81, 43.89) or total gastrectomy (43.91, 43.99)[11]. Data from the HDR database were merged in a deterministic record-linkage procedure with those from the Regional Death Registry and histological referrals. Prior to the analysis, data were anonymized, assigning a unique identifier code to each patient. Access to data was granted by the Regional Health Authority and the Department of Healthcare Management of AVR hospitals. The study was conducted in compliance with Italian legislation on privacy (Art.20-21, DL 196/2003) and approved by the Ethics Committee of each of the centers participating in the study.

Data from the pathological report of selected patients were reviewed by a surgeon (PM) and the following information was collected in a common database: exact number of lymph nodes removed; dissected stations sent to the pathologist; tumor size; site and macroscopic classification according to Japanese guidelines[2]; Lauren classification; microscopic resection line infiltration; total number of dissected and pathological lymph nodes; and T and N stage according to 7th UICC classification[3].

Patients with documented macroscopic metastases submitted to palliative treatments were excluded from the study, while those with only microscopic involvement not identified by surgeons were included. No information was available on the extension of surgical lymph node dissection and there were no common surgical or pathological guidelines for the 7 general hospitals. After surgery, patients underwent treatment in accordance with the guidelines of the hospital they attended.

Patients were subdivided into two groups to evaluate the correlation between the number of lymphatic stations picked up and the number of lymph nodes retrieved. In group A, only one formalin-fixed specimen per patient was sent to the pathologist who picked up lymph nodes separately from the greater and lesser curvature. Group B comprised patients for whom at least one more lymphatic station was separately removed on fresh stomach specimens and immediately fixed in formalin. Special attention was paid to pathological reports in which more than 6 separate stations were evaluated because in some cases this may indicate that some kind of lymphadenectomy has been performed. Patients with ≥ 16 lymph nodes dissected were considered as correctly classified on the basis of the new UICC TNM staging system[3].

The potential impact of the number of dissected specimens on survival was investigated by performing a separate sensitivity analysis for patients correctly staged with < 16 or ≥ 16 dissected lymph nodes. Overall survival was considered as outcome measure up to the last follow up on 31st December 2011.

We compared patient and tumor characteristics in the two groups using percentages and the χ2 test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate long-term survival between groups of patients and the log-rank test was used to compare survival curves. Taking into account all the information collected for the study, we calculated the adjusted hazard ratios and 95%CI using a Cox regression model to evaluate the impact on survival of the number of stations sent to the pathologist and the number of lymph nodes removed. Given the nature of the study design and the endpoints, a prior sample size was not calculated. All tests were two-sided with a significance level of < 0.05. No multiplicity test correction was done. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 software for Windows.

One thousand two hundred and three pathological reports of patients submitted to radical resection for gastric cancer from 2004 to 2008 were retrieved from the 7 AVR general hospital databases. Ninety-one (7.6%) patients were excluded because the pathological report described gastric diseases other than cancer or surgical procedures other than radical gastrectomy. Clinical and pathological characteristics of the remaining 1112 patients are presented in Table 1. No significant differences were observed between either group of patients in terms of Charlson comorbidity index, type of gastrectomy performed, infiltrated margins and Lauren classification. Conversely, a significant difference was found with respect to age, gender, T or N stage and number of retrieved lymph nodes.

| All patients(n = 1112) | Group A(n = 401) | Group B(n = 711) | P | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 448 (40.29) | 144 (35.91) | 304 (42.76) | 0.0254 |

| Male | 664 (59.71) | 257 (64.09) | 407 (57.24) | |

| Age (yr) | ||||

| ≤ 75 | 621 (55.85) | 176 (43.89) | 445 (62.59) | < 0.0001 |

| > 75 | 491 (44.15) | 225 (56.11) | 266 (37.41) | |

| Charlson score | ||||

| 0 | 869 (78.15) | 312 (77.80) | 557 (78.34) | 0.5067 |

| 1 | 195 (17.54) | 68 (16.96) | 127 (17.86) | |

| ≥ 2 | 48 (4.32) | 21 (5.24) | 27 (3.80) | |

| Procedure | ||||

| Partial gastrectomy | 674 (60.61) | 257 (64.09) | 417 (58.65) | 0.0746 |

| Total gastrectomy | 438 (39.39) | 144 (35.91) | 294 (41.35) | |

| Lymph nodes | ||||

| N0 | 426 (38.45) | 72 (43.22) | 254 (35.77) | 0.0126 |

| N1 | 176 (15.88) | 67 (16.83) | 109 (15.35) | |

| N2 | 180 (16.25) | 65 (16.33) | 115 (16.20) | |

| N3a | 200 (18.05) | 63 (15.83) | 137 (19.30) | |

| N3b | 126 (11.37) | 31 (7.79) | 95 (13.38) | |

| Missing | 4 | 3 | 1 | |

| No. lymph nodes removed | ||||

| < 16 | 389 (34.98) | 250 (62.34) | 139 (19.55) | < 0.0001 |

| ≥ 16 | 723 (65.02) | 151 (37.66) | 572 (80.45) | |

| T | ||||

| T1 | 232 (20.86) | 80 (19.95) | 152 (21.38) | 0.008 |

| T2 | 162 (14.57) | 59 (14.71) | 103 (14.49) | |

| T3 | 317 (28.51) | 94 (23.44) | 223 (31.36) | |

| T4 | 401 (36.06) | 168 (41.90) | 233 (32.77) | |

| Margin | 25 | 156 | ||

| Infiltrated | 76 (8.16) | 28 (7.45) | 48 (8.65) | 0.5111 |

| Not infiltrated | 855 (91.84) | 348 (92.55) | 507 (91.35) | |

| Missing | 181 | |||

| Lauren classification | ||||

| Intestinal | 807 (74.24) | 291 (75.58) | 516 (73.50) | 0.4532 |

| Diffuse/mixed | 280 (25.76) | 94 (24.42) | 186 (26.50) | |

| Missing | 25 | 16 | 9 | |

Group A comprised 401 patients and group B, 711 patients. Considering the number of dissected lymph nodes in the 2 groups, 62.3% of group A patients could not be adequately staged with the TNM classification because of insufficient lymph node retrieval (< 16 lymph nodes). Conversely, in group B (separate dissection), an insufficient number of lymph nodes was retrieved in only 19.4% of patients. This difference was significant (P < 0.0001). As the difference in the number of lymph nodes removed (< 16 vs≥ 16) was not statistically significant in multivariate analysis, this variable was removed from the model by a stepwise procedure (Table 2).

| Parameter | HR | 95%CI | P | ||

| No. specimens sent to pathologist | Group A vs Group B | 1.239 | 1.053 | 1.458 | 0.0098 |

| Gender | M vs F | 1.235 | 1.046 | 1.457 | 0.0127 |

| Age, yr | > 75 vs ≤ 75 | 2.190 | 1.858 | 2.582 | < 0.0001 |

| T | 2 vs 1 | 1.202 | 0.843 | 1.715 | 0.3087 |

| 3 vs 1 | 1.957 | 1.438 | 2.663 | < 0.0001 | |

| 4 vs 1 | 3.410 | 2.518 | 4.618 | < 0.0001 | |

| N | + vs - | 2.166 | 1.753 | 2.676 | < 0.0001 |

| Type of procedure | Total vs partial | 1.327 | 1.132 | 1.556 | 0.0005 |

| Lauren classification | Diffuse-mixed vs intestinal | 1.256 | 1.051 | 1.500 | 0.0119 |

An overall survival of 35.6 mo (95%CI: 31.7-42.7) was observed for the entire case series, with a median follow up of 69 mo. With respect to the number of removed stations, the separate specimen group B showed significantly higher survival rates than the A group [46.1 mo (95%CI: 36.5-56.0) vs 27.7 mo (95%CI: 21.3-31.9); P = 0.0001] (Figure 1). Furthermore, in the multivariate model, which included all the available prognostic factors, group A patients showed a higher risk of death than those in group B (HR = 1.24; 95%CI: 1.05-1.46). Of note, the 264 patients in the latter group for whom more than 6 separate stations (4 more than in group A) were considered showed the best survival rates with a median survival of 56.7 mo (95%CI: 44.43-56.7; P < 0.0001).

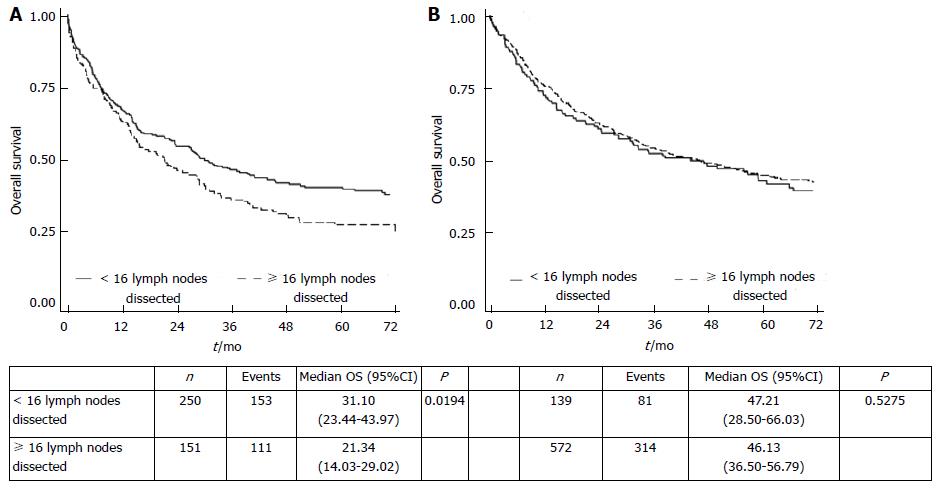

In group A, overall survival was significantly higher in patients with < 16 lymph nodes retrieved than in those with ≥ 16 lymph nodes, whereas in the separate specimen group B no difference was observed between patients with < 16 or ≥ 16 lymph nodes (Figure 2). The number of positive lymph nodes in group A patients with ≥ 16 lymph nodes retrieved was twofold higher that of negative lymph nodes (P < 0.001). In contrast, group B patients with ≥ 16 retrieved lymph nodes did not show such a different distribution of positive lymph nodes (P = 0.067) (Table 3). However, in multivariate analysis the interaction term between group and number of lymph nodes retrieved was not statistically significant, indicating no difference in the risk of death between patients with < 16 or ≥ 16 lymph nodes in either group.

The extension of lymphadenectomy and the number of lymph nodes to remove for correct gastric cancer staging is still matter of great debate. The UICC TNM 7th edition classification considers 16 lymph nodes as the minimum number required for N staging[3], independently of lymphatic station dissection. The N ratio classification states that fewer nodes suffice, but even though lower sensitivity has been reported when fewer lymph nodes are dissected, the most effective minimum number has yet to be defined[4].

Lymph node dissection has finally been acknowledged as a crucial practice in the west and several studies have reported better results for patients treated with D2 dissection[12,13]. However, an important problem associated with the type of lymphadenectomy performed is that of non compliance (less extensive dissection than specified) and contamination (more extensive dissection than specified)[14]. All these factors must be taken into consideration when a multicenter study is proposed in order to standardize patients operated on in different institutions and to facilitate the comparison of results.

Increasing interest is being shown in the creation of large international databases to collect information on patients undergoing surgical treatment in different countries. Although an interesting initiative, the different approach taken to lymphadenectomy in different countries could represent a problem. The most widely proposed index to verify the quality of lymphadenectomy and the extension of lymph node dissection is the number of retrieved lymph nodes[5,6], but this alone is probably not enough to confirm the correctness of treatment. In their 1998 multicenter study, Estes et al[15] observed a significant survival benefit for patients who had a post-surgery histology report clearly supporting a curative resection compared to those whose histologic documentation was insufficient to support such a conclusion.

The present work focused on patients who were part of a previous retrospective cohort study[16] carried out in 7 hospitals within the same area where there are no common surgical or pathological guidelines. We evaluated the relationship between the number of retrieved lymph nodes, number of dissected lymphatic stations and survival without, however, having any information on surgical lymphadenectomy. Whilst there were some dissimilarities between the 2 groups, i.e., group B included younger patients, more T3 than T4 cases and higher lymph node involvement than group A, all patients were considered radically resected and comparable. We also assessed whether the pathological report could represent a sort of surgical quality index.

The first interesting result from our study was that an insufficient number of lymph nodes was obtained in the majority of group A patients. The removal of only one fixed specimen is normal practice in D0 dissection and several authors have reported that D0 and D1 dissections frequently do not permit correct staging[17]. Although we cannot be certain whether a low number of collected lymph nodes was due to insufficient lymphadenectomy or to difficult retrieval from formalin-fixed specimens, we can confirm that an increased number of picked up lymph node stations was correlated with a higher number of retrieved lymph nodes.

In 2006, Coburn et al[18] observed better survival rates in radically resected patients when a higher number of lymph nodes were collected. This result was confirmed for all stages but was more evident for stages I and II. Survival rates in Coburn’s study were positively modified by stage migration when the number of lymph nodes was > 15, but multivariate analysis also suggested an independent role for the number of nodes retrieved[18]. In our study, although patients with ≥ 16 lymph nodes removed showed better survival in univariate analysis, this was not confirmed in multivariate analysis.

Another interesting result from our study was the correlation between the number of dissected lymph node stations and survival. The survival rate of group B patients who had at least one more lymphatic station separately removed was significantly higher than that of group A (P < 0.0001) and increased when 6 or more separate stations were dissected. A description of > 2 stations in the pathological report was identified as an independent prognostic factor in multivariate analysis. Interestingly, this finding was independent of N stage and consequently was not influenced by the Will Rogers phenomenon. Multivariate analysis did not confirm the same independent role of the “> 2 stations” variable when < or ≥ 6 stations were considered [HR = 1.23; P = 0.075 (95%CI: 0.97-1.54)].

The dissection of separate stations only represents a technical procedure and cannot be considered as a therapeutic option designed to improve survival. However, this type of dissection of fresh specimens probably identifies patients treated in centers of excellence in gastric cancer. Thus, survival rates could potentially be improved by lymphadenectomy rather than by post-surgical procedures, and the number of dissected stations could be used as a quality index in multicenter studies.

Notably, group A patients with ≥ 16 lymph nodes removed showed significantly worse survival rates than those with < 16 lymph nodes resected. This may have been due to the different distribution of positive lymph nodes in patients with ≥ 16 lymph nodes retrieved in the two study groups. We found a higher number of positive lymph nodes in the ≥ 16 lymph node group, probably because pathological lymph nodes are often larger and easier to remove (Table 3). Although these patients were better staged because an adequate number of lymph nodes were available for TNM classification, they had a poorer prognosis. This suggests that the number of retrieved lymph nodes alone cannot identify correctly treated patients from a surgical point of view. An adequate number of dissected stations must be removed.

Separate lymphatic station dissection of fresh specimens increases the number of nodes retrieved, permitting better staging. This procedure, common in centers specializing in the treatment of gastric cancer, permits a greater quality control of lymphadenectomy and provides more standardized data for large databases. In our experience, ≥ 16 lymph nodes retrieved identified patients with a poor prognosis when stations were not picked up separately, suggesting that the number of lymph nodes removed cannot itself be considered as a quality indicator. Unfortunately, this is a retrospective study and no information was available on the extension of the lymphadenectomy performed or on postoperative therapy. However, our statistical analyses confirmed the above correlations. Thus, although separate station dissection in fresh specimens is a time-consuming procedure and not yet a requisite of the TNM classification, its potential importance cannot be ignored.

The following are acknowledged as co-authors: Francesco Buccoliero, MD, Surgical Unit and Evandro Nigrisoli, Pathlogy Unit, Bufalini Hospital, Cesena; Pier Sante Zattini, Surgical Unit Lugo General Hospital; Filippo Pierangeli, Surgical Unit, Infermi Hospital, Faenza; Giorgio Maria Verdecchia, Advanced Oncological Surgery Unit and Luigi Serra, Pathology Unit, Morgagni-Pierantoni Hospital, Forlì; Paolo Soliani, Surgical Unit and Giuseppe Lanzanova, Pathology Unit, Santa Maria delle Croci Hospital, Ravenna; Gianfranco Francioni, Surgical Unit and Massimo Brisigotti, Pathology Unit, Degli Infermi Hospital, Rimini; Gianluca Garulli, Surgical Unit, Ceccarini Hospital, Riccione, Italy.

Lymph node dissection is performed as part of the surgical resection of gastric cancer to stage lymphatic diffusion. In Eastern Asia, separate station lymph node dissection is routinely carried out in the operating theatre immediately after tumor resection, whereas in the West stomach specimens are formalin-fixed en bloc and sent to the pathologist for evaluation.

In the area of gastric cancer, the current research hotspot is how to improve staging accuracy.

Lymph node pick up by separate stations could be an indicator of patients treated at centers of excellence in gastric cancer.

Accurate lymph node pick up by separate stations leads to better tumor staging and facilitates the choice of subsequent treatments.

Lymph node pick up is a procedure performed by a surgeon or pathologist after surgical resection to detect all the lymph nodes in the removed specimen.

An interesting article in its field, focusing on lymph node dissection by separate stations which is a common procedure in East Asia. This manuscript demonstrates that patients with separate lymph node station have better survival than those without.

P- Reviewer: Coccolini F, Huang KH, Mocellin S S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Seevaratnam R, Bocicariu A, Cardoso R, Mahar A, Kiss A, Helyer L, Law C, Coburn N. A meta-analysis of D1 versus D2 lymph node dissection. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15 Suppl 1:S60-S69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1723] [Cited by in RCA: 1897] [Article Influence: 135.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sobin LH, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumors. 7th ed. New York: John Wiley and Sons 2009; . |

| 4. | Marchet A, Mocellin S, Ambrosi A, Morgagni P, Garcea D, Marrelli D, Roviello F, de Manzoni G, Minicozzi A, Natalini G. The ratio between metastatic and examined lymph nodes (N ratio) is an independent prognostic factor in gastric cancer regardless of the type of lymphadenectomy: results from an Italian multicentric study in 1853 patients. Ann Surg. 2007;245:543-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 287] [Cited by in RCA: 314] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Degiuli M, Sasako M, Calgaro M, Garino M, Rebecchi F, Mineccia M, Scaglione D, Andreone D, Ponti A, Calvo F. Morbidity and mortality after D1 and D2 gastrectomy for cancer: interim analysis of the Italian Gastric Cancer Study Group (IGCSG) randomised surgical trial. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:303-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kodera Y, Fujiwara M, Ohashi N, Nakayama G, Koike M, Morita S, Nakao A. Laparoscopic surgery for gastric cancer: a collective review with meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:677-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Roviello F, Rossi S, Marrelli D, Pedrazzani C, Corso G, Vindigni C, Morgagni P, Saragoni L, de Manzoni G, Tomezzoli A. Number of lymph node metastases and its prognostic significance in early gastric cancer: a multicenter Italian study. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94:275-280; discussion 274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Morgagni P, Garcea D, Marrelli D, de Manzoni G, Natalini G, Kurihara H, Marchet A, Vittimberga G, Saragoni L, Roviello F. Does resection line involvement affect prognosis in early gastric cancer patients An Italian multicentric study. World J Surg. 2006;30:585-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Marrelli D, De Stefano A, de Manzoni G, Morgagni P, Di Leo A, Roviello F. Prediction of recurrence after radical surgery for gastric cancer: a scoring system obtained from a prospective multicenter study. Ann Surg. 2005;241:247-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Seevaratnam R, Bocicariu A, Cardoso R, Yohanathan L, Dixon M, Law C, Helyer L, Coburn NG. How many lymph nodes should be assessed in patients with gastric cancer A systematic review. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15 Suppl 1:S70-S88. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm. |

| 12. | Songun I, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, Sasako M, van de Velde CJ. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: 15-year follow-up results of the randomised nationwide Dutch D1D2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:439-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1140] [Cited by in RCA: 1309] [Article Influence: 87.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Roviello F, Marrelli D, Morgagni P, de Manzoni G, Di Leo A, Vindigni C, Saragoni L, Tomezzoli A, Kurihara H. Survival benefit of extended D2 lymphadenectomy in gastric cancer with involvement of second level lymph nodes: a longitudinal multicenter study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:894-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bunt AM, Hermans J, Boon MC, van de Velde CJ, Sasako M, Fleuren GJ, Bruijn JA. Evaluation of the extent of lymphadenectomy in a randomized trial of Western- versus Japanese-type surgery in gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:417-422. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Estes NC, MacDonald JS, Touijer K, Benedetti J, Jacobson J. Inadequate documentation and resection for gastric cancer in the United States: a preliminary report. Am Surg. 1998;64:680-685. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Altini M, Carretta E, Morgagni P, Carradori T, Ciotti E, Prati E, Garcea D, Amadori D, Falcini F, Nanni O. Is a clear benefit in survival enough to modify patient access to the surgery service A retrospective analysis in a cohort of gastric cancer patients. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:159-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | de Manzoni G, Verlato G, Roviello F, Morgagni P, Di Leo A, Saragoni L, Marrelli D, Kurihara H, Pasini F. The new TNM classification of lymph node metastasis minimises stage migration problems in gastric cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:171-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Coburn NG, Swallow CJ, Kiss A, Law C. Significant regional variation in adequacy of lymph node assessment and survival in gastric cancer. Cancer. 2006;107:2143-2151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |