Published online Jun 27, 2013. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v5.i6.210

Revised: May 22, 2013

Accepted: June 1, 2013

Published online: June 27, 2013

Processing time: 78 Days and 17.5 Hours

A retained bile duct stone after operation for cholelithiasis still occurs and causes symptoms such as biliary colic and obstructive jaundice. An endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), followed by stone extraction, are usually an effective treatment for this condition. However, these procedures are associated with severe complications including pancreatitis, bleeding, and duodenal perforation. Nitrates such as glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) and isosorbide dinitrate (ISDN) are known to relax the sphincter of Oddi. In 6 cases in which a retained stone was detected following cholecystectomy, topical nitrate drip infusion via cystic duct tube (C-tube) was carried out. Retained stones of 2-3 mm diameter and no dilated common bile duct in 3 patients were removed by drip infusion of 50 mg GTN or 10 mg ISDN, which was the regular dose of intravenous injection. Three other cases failed, and EST in 2 cases and endoscopic biliary balloon dilatation in 1 case were performed. One patient developed an adverse event of nausea. Severe complications were not observed. We consider the topical nitrate drip infusion via C-tube to be old but safe, easy, and inexpensive procedure for retained bile duct stone following cholecystectomy, inasmuch as removal rate was about 50% in our cases.

Core tip: In 6 cases in which a retained stone was detected following cholecystectomy, topical nitrate drip infusion via cystic duct tube (C-tube) was carried out. Retained stones of 2-3 mm diameter with no dilated common bile duct in 3 patients were removed by drip infusion of glyceryl trinitrate or isosorbide dinitrate. Three other cases failed, and endoscopic sphincterotomy in 2 cases and endoscopic biliary balloon dilatation in 1 case were performed. The topical nitrate drip infusion via C-tube is old but safe, easy, and inexpensive procedure for retained stone following cholecystectomy, inasmuch as removal rate was about 50% in our cases.

- Citation: Shoji M, Sakuma H, Yoshimitsu Y, Maeda T, Nakai M, Ueda H. Topical nitrate drip infusion using cystic duct tube for retained bile duct stone: A six patients case series. World J Gastrointest Surg 2013; 5(6): 210-215

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v5/i6/210.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v5.i6.210

Common bile duct (CBD) stones are identified in approximately 4%-20% of symptomatic patients who had undergone cholecystectomies[1,2]. When a routine intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) is not performed in patients without symptoms, 0.9% of patients following cholecystectomy will present a retained stone, requiring intervention[3]. This means that most choledocholithiasis remain silent or pass spontaneously into the duodenum and some may present with complications including biliary obstruction, acute pancreatitis, and cholangitis in the future. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) or endoscopic papillary balloon dilation (EPBD) is a well-established therapeutic procedure for the extraction of a retained stone. However, this is an invasive examination and associated with specific complications such as acute pancreatitis, hemorrhage, and duodenal perforation, or even death. Its morbidity and mortality rates are up to 10.0% and 0.4%, respectively[1]. Moreover, after EST, the function of sphincter of Oddi (SO) is destroyed and the loss of this physiologic barrier between duodenum and biliary tract results in duodenocholedochal reflux and bacterial colonization of the biliary tract. Then, the presense of bacteria in the biliary system causes late complications including recurrence of stones, recurrent ascending cholangitis and even malignancy[4].

It is preferable to select a safer procedure for a retained stone so as to reduce early or late complications. When the existence of a retained stone is suspected, a cystic duct tube (C-tube) is surgically inserted into the cystic duct and the CBD can be drained via the cystic duct, and the retained stone can be managed, if necessary, in the postoperative period. It has been reported that topical application of nitrate effectively relaxes SO and should be taken into account for the removal of a retained stone[5]. Therefore, a topical nitrate drip infusion procedure using a cystic duct tube was tested on 6 patients with retained stones after cholecystectomies.

We report 6 patients after cholecystectomy with retained stones, who experienced the topical nitrate drip infusion procedure using a C-tube. The main characteristics of each are summarized in Table 1.

| Characteristics | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 |

| Age (yr) | 76 | 69 | 37 | 75 | 64 | 69 |

| Sex | Man | Man | Woman | Woman | Woman | Man |

| Diagnosis | Acute cholecystitis | Acute cholecystitis | Choledocholithiasis | Choledocholithiasis | Choledocholithiasis | Acute cholecystitis |

| Preoperative drainage | – | EST | – | – | – | – |

| Surgical method | Open | Laparoscopic | Laparoscopic | Laparoscopic | Laparoscopic | Open |

| IOC defect | – | – | + | + | – | – |

| Stone diameter (mm) | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 6 |

| CBD diameter (mm) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 12 |

| Nitrate | GTN 50 mg + NS 200/2 h | GTN 50 mg + NS 500/5 h | ISDN 10 mg + NS 500/3 h | GTN 10 mg + NS 500/3 h | ISDN 5 mg + NS 250/3 h | GTN 50 mg + NS 250/2.5 h |

| Trial | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 4 |

| Stone removal | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Complication | – | – | – | Nausea | – | – |

| 2nd procedure | – | – | – | EST | EST | EPBD |

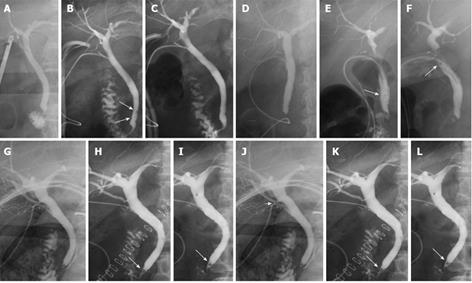

A 76-year-old man complained of epigastralgia and jaundice. He had undergone distal partial gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y reconstruction for early gastric cancer 3 years ago. Computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) did not show choledocholithiasis. Then, an open cholecystectomy was performed. The brown pigment stones and purulent exudate were seen in the gallbladder. IOC could not identify a filling defect (Figure 1A), but it was probable that a retained stone existed and a C-tube was placed. On postoperative day (POD) 7, cholangiography demonstrated a 2 mm-diameter stone (Figure 1B). Infusions of 50 mg of GTN and 200 mL of normal saline were given using a C-tube for 2 h. He had an episode of biliary colic and on the next day the retained stone disappeared (Figure 1C). He was discharged on POD 13.

A 69-year-old man was referred to us complaining of abdominal pain and fever. He had a past history of cerebral hemorrhage and left hemiplegia. Since CT revealed severe acute cholangitis due to cholecystocholedocholithiasis, he needed biliary drainage. EST with stone extraction was performed. After 2 mo, he had recurrent biliary tract symptoms. CT identified recurrent CBD stones. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed. IOC could not identify a filling defect (Figure 1D), but a retained stone was suspected and a C-tube was placed. On POD 9, cholangiography showed 2 mm-diameter stones at distal CBD (Figure 1E). Infusions of 50 mg of GTN and 500 mL of normal saline were given three times and the retained stones were removed on POD 15 (Figure 1F). He needed postoperative rehabilitation and was discharged on POD 31.

A 37-year-old woman presented with abdominal pain. CT scan revealed stones in the gallbladder and distal CBD. For this, laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed. IOC demonstrated a 3 mm-diameter filling defect. However, since the CBD was not dilated, laparoscopic CBD exploration was not carried out. A C-tube was placed percutaneously. The brown pigment stones were seen in the gallbladder. On POD 4, when cholangiography via C-tube identified the retained stone, 10 mg of isosorbide dinitrate and 500 mL of normal saline were topically infused via a C-tube. The following day the retained stone was removed and she was discharged on POD 11.

A 75-year-old woman was positive for fecal occult blood test and total colonoscopy detected early sigmoid colon cancer. CT revealed stones in the gallbladder and distal CBD. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and sigmoidectomy were performed at the same time. IOC demonstrated a 5 mm-diameter filling defect. Diameter of the CBD was 8 mm, and extraction of the stone was not carried out. On POD 5, cholangiography via C-tube identified the retained stone, and 10 mg of GTN and 500 mL of normal saline were topically infused. Because she complained of nausea, the treatment was stopped. Nausea disappeared as soon as the drip infusion stopped. On POD 8, EST was performed and the retained stone was extracted. She needed rehabilitation for poor performance status and was discharged on POD 28.

A 64-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with fever and liver dysfunction. CT/MRCP revealed no evidence of a CBD stone. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed. There were about 200 brown pigment stones in the gallbladder. IOC could not show a filling defect, but contrast media did not flow into the duodenum (Figure 1G). A C-tube was placed, and cholangiography showed a 3 mm-diameter floating stone on POD 5 (Figure 1H). Infusions of 5 mg of ISDN and 250 mL of normal saline were given 6 times, but the stone was not removed (Figure 1I). EST was performed on POD 9. The stone faded away and the C-tube was removed. She was discharged on POD 15.

A 69-year-old man presented with abdominal pain and anorexia. He underwent a carotid endarterectomy and had been treated with an antiplatelet agent. Transabdominal ultrasonography and CT revealed gallstones, pericholecystic fluid, and gallbladder wall thickening. He was diagnosed as acute cholecystitis, and open cholecystectomy was performed. Since an injury to posterior superior bile duct was suspected by IOC (white arrow head) (Figure 1J), a C-tube was placed. On POD 7, cholangiography showed a 6 mm-diameter retained stone at distal CBD without biliary leak (Figure 1K). Infusions of 50 mg of GTN and 250 mL of normal saline were given 4 times, but the stone could not be removed (Figure 1L). EPBD and extraction of stone with rendezvous technique using a C-tube was performed on POD 11. He was discharged without complication on POD 19.

In our cases, the rate of removing retained stones by topical nitrate drip infusion using the C-tube was 50%. In three successful patients, the diameter of retained stone was 2-3 mm and CBD was not dilated. All of them were asymptomatic postoperatively. Infusion trial ranged from 1-3 times. On the other hand, the procedure failed in three patients. The diameter of retained stone was 3-6 mm and CBD had a range of 6-12 mm. Infusion trial ranged from 1-6 times. Topical application of GTN and ISDN was used intravenously at the regular dose and there were no side effects such as hypotension and headache. One patient developed an adverse event of nausea but severe complications were not observed. EST in 2 cases and EPBD in 1 case were performed as second procedures.

Spontaneous stone migration occurred in 21% of patients with choledocholithiasis within one month and 83% of those were asymptomatic. The size of a retained stone (dichotomized at 8 mm) is the only independent factor to predict migration through duodenum[6]. However, Whether migration depends on the relationship between a size of a retained stone and a diameter of CBD has not been reported. Gallstones with a diameter up to 5 mm can migrate in CBD and trigger acute pancreatitis, cholangitis, and hepatic abscess[7]. In patients with retained stones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, 35% of these passed calculi spontaneously within 6 wk of operation without ERCP, while 65% of these had persistent bile duct stones retrieved by endoscopic intervention[8]. Therefore, it is difficult to manage a retained stone with no dilated CBD after cholecystectomy.

Recently, before surgery, MRCP and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) have been used to accurately estimate the biliary system without cannulating the ducts. Both MRCP and EUS have sensitivity and specificity of over 90%[1,2]. However, when a retained bile duct stone is less than

4 mm or CBD is dilated more than 10 mm, detection by both ERCP and MRCP may not be possible[9]. Small stones can cause acute biliary pancreatitis. At the time of surgery, IOC is an effective procedure of identifying a retained bile duct stone. Laparoscopic IOC has a sensitivity of 80.0%-92.8%, and specificity of 76.2%-97.0%[1]. There is a time lag between preoperative examinations and the operation, and IOC can reflect bile duct stones in real time. During an operation, when it was suspected in a series of examinations that a patient still had CBD stones, the surgeon needs to select an operative stone extraction (laparoscopic/open or transcystic duct/choledochostomy) or pre/postoperative ERCP. There is no difference in performance for morbidity and mortality when laparoscopic choledochotomy and perioperative ERCP are compared. However, hospital stay is shorter for patients who had undergone laparoscopic choledochotomy[2]. EPBD had less infections over the short and long-term[10] and less stone recurrence over the long term than EST[11]. However, Disario et al[12] had reported that EPBD showed an increase of morbidity rates and death for pancreatitis when compared with EST for biliary stone extraction.

For years, the T-tube has been used to decompress the biliary duct and avoid biliary complications in the postoperative period. It also makes postoperative cholangiography possible, and if a retained stone is detected, the stone can be extracted by choledochoscopy via the T-tube. However, the T-tube causes complications up to 10% such as bile peritonitis due to T-tube dislocation, which can lead to re-operation and even death, and requires a prolonged hospital stay. Recently, it was reported that primary closure might be effective for T-tube drainage after choledochotomy in preventing postoperative complications[13]. In contrast, the C-tube, which is placed in the CBD via the cystic duct has the advantages of easier surgical technique, less complication and shorter hospital stay. It is possible that postoperative direct cholangiography repeatedly performed on various conditions such as contrast media concentration and posture of a patient would show the same results as the T-tube.

The non-operative elimination of a retained stone has long been tried because repeated surgery is undesirable. Staritz et al[5,14] first reported that GTN effectively decreased papillary baseline pressure, relaxed SO muscle, and facilitated bile flow into duodenum. GTN had no influence on SO motility. Also, sublingual application of GTN facilitated endoscopic extraction of CBD stones. GTN is a donor of nitric oxide, which is one important element of a non-adrenergic non-cholinergic pathway to the SO[15]. Luman et al[16] reported that topical application of 5 or 10 mg of GTN reduced tonic and phasic contractions of SO without side effects. Wehrmann et al[17] reported that topical application of 10 mg of GTN or 10 mg of ISDN evoked a profound inhibition of SO motility, and the effect of ISDN was longer than of GTN. Both GTN and ISDN were not accompanied with adverse effects. In two meta-analyses[18,19], prophylactic GTN administered by either sublingual or transdermal route was useful for prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis. The main adverse events of nitrate were hypotension and headache. However, they were easily managed by conventional treatment. We consider the adverse events are rare because blood concentration of a drug in a topical application is lower than in an intravenous administration.

It is estimated that the incidence of choledocholithiasis is 15%-40% in patients over 60 years old compared with 8%-15% in those under 60 years old undergoing open cholecystectomy for cholelithiasis[20]. Among patients at high-risk (high age, surgically altered anatomy as in patient 1, and antiplatelet agents treatment as in patient 6), which are increasing in recent years, the non-invasive procedure for retained stone is preferable. Also, in the patients with no dilated CBD who had undergone a choledochotomy postoperative bile duct stricture tends to occur, which is a life-threatening complication requiring expertise on the part of surgeon, radiologist, and gastroenterologist[21]. Representative medical treatments for retained stones are gallstone resolution and extracorporeal shock waves. Presently however, results have not been clear-cut in clinical practice. A recent study suggested that direct peroral cholangioscopy can remove a retained stone without complication[22].

Hence, inasmuch as the topical nitrate drip infusion via C-tube is an old procedure, it is safe, easy, and inexpensive for a retained bile duct stone following cholecystectomy. The removal rate is admittedly not so high, about 50% in our cases. In particular, it is effective in cases in which stone diameter is smaller than 6 mm or CBD is not dilated. There are two principal mechanisms by which topical nitrate infusion removes retained stones. First, nitrates relax SO. Topical dose of nitrates can be as effective as an intravenous dose. Secondly, flow of a drip infusion can drain the retained stone after dilatation of SO with nitrates. Main adverse events are recognized such as biliary colic and nausea in patient 4 and pancreatitis can occur from blockage of pancreatic exocrine secretions by retained stones. When infusing a topical nitrate, the patient remains under careful supervision. If not successful, the C-tube is useful for the rendezvous technique and clearance by ERCP with EST or EPBD as in patient 6.

In conclusion, our cases demonstrated the potential effectiveness of topical nitrate drip infusion using a C-tube for a retained stone when stone size is small and CBD is not dilated. An indication for a kind and dose of nitrate, and volume and speed of drip infusion should be taken into consideration. However, this is the small sample size and more studies including randomized control trials are required in the future. These may show there is an advantage of the topical nitrate drip infusion using a C-tube for retained stone before an endoscopic procedure.

P- Reviewers Chong VH, Leitman IM, Zippi M S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Lu YJ

| 1. | Williams EJ, Green J, Beckingham I, Parks R, Martin D, Lombard M. Guidelines on the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Gut. 2008;57:1004-1021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Frossard JL, Morel PM. Detection and management of bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:808-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Horwood J, Akbar F, Davis K, Morgan R. Prospective evaluation of a selective approach to cholangiography for suspected common bile duct stones. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92:206-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Seo DB, Bang BW, Jeong S, Lee DH, Park SG, Jeon YS, Lee JI, Lee JW. Does the bile duct angulation affect recurrence of choledocholithiasis? World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4118-4123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Staritz M, Poralla T, Ewe K, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH. Effect of glyceryl trinitrate on the sphincter of Oddi motility and baseline pressure. Gut. 1985;26:194-197. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Frossard JL, Hadengue A, Amouyal G, Choury A, Marty O, Giostra E, Sivignon F, Sosa L, Amouyal P. Choledocholithiasis: a prospective study of spontaneous common bile duct stone migration. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:175-179. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Frossard JL, Steer ML, Pastor CM. Acute pancreatitis. Lancet. 2008;371:143-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 524] [Cited by in RCA: 512] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Collins C, Maguire D, Ireland A, Fitzgerald E, O’Sullivan GC. A prospective study of common bile duct calculi in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: natural history of choledocholithiasis revisited. Ann Surg. 2004;239:28-33. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Moon JH, Cho YD, Cha SW, Cheon YK, Ahn HC, Kim YS, Kim YS, Lee JS, Lee MS, Lee HK. The detection of bile duct stones in suspected biliary pancreatitis: comparison of MRCP, ERCP, and intraductal US. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1051-1057. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Weinberg BM, Shindy W, Lo S. Endoscopic balloon sphincter dilation (sphincteroplasty) versus sphincterotomy for common bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD004890. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Tanaka S, Sawayama T, Yoshioka T. Endoscopic papillary balloon dilation and endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones: long-term outcomes in a prospective randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:614-618. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Disario JA, Freeman ML, Bjorkman DJ, Macmathuna P, Petersen BT, Jaffe PE, Morales TG, Hixson LJ, Sherman S, Lehman GA. Endoscopic balloon dilation compared with sphincterotomy for extraction of bile duct stones. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1291-1299. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Zhu QD, Tao CL, Zhou MT, Yu ZP, Shi HQ, Zhang QY. Primary closure versus T-tube drainage after common bile duct exploration for choledocholithiasis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396:53-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Staritz M, Poralla T, Dormeyer HH, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH. Endoscopic removal of common bile duct stones through the intact papilla after medical sphincter dilation. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:1807-1811. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Kaufman HS, Shermak MA, May CA, Pitt HA, Lillemoe KD. Nitric oxide inhibits resting sphincter of Oddi activity. Am J Surg. 1993;165:74-80. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Luman W, Pryde A, Heading RC, Palmer KR. Topical glyceryl trinitrate relaxes the sphincter of Oddi. Gut. 1997;40:541-543. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Wehrmann T, Schmitt T, Stergiou N, Caspary WF, Seifert H. Topical application of nitrates onto the papilla of Vater: manometric and clinical results. Endoscopy. 2001;33:323-328. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Bai Y, Xu C, Yang X, Gao J, Zou DW, Li ZS. Glyceryl trinitrate for prevention of pancreatitis after endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. Endoscopy. 2009;41:690-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chen B, Fan T, Wang CH. A meta-analysis for the effect of prophylactic GTN on the incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis and on the successful rate of cannulation of bile ducts. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Esber EJ, Sherman S. The interface of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1996;6:57-80. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Lillemoe KD. Current management of bile duct injury. Br J Surg. 2008;95:403-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lee YN, Moon JH, Choi HJ, Min SK, Kim HI, Lee TH, Cho YD, Park SH, Kim SJ. Direct peroral cholangioscopy using an ultraslim upper endoscope for management of residual stones after mechanical lithotripsy for retained common bile duct stones. Endoscopy. 2012;44:819-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |