Published online Jul 27, 2010. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v2.i7.247

Revised: February 22, 2010

Accepted: February 27, 2010

Published online: July 27, 2010

Abdominal wall actinomycosis is a rare disease frequently associated with the presence of an intra uterine device. We report on a case of a 47-year-old woman who had used an intrauterine device for many years and had removed it about a month prior to the identification of an abdominal wall abscess caused by Actinomyces israelii. The abscess mimicked a malignancy and the patient underwent a demolitive surgical treatment. The diagnosis was obtained only after histopathological examination. Postoperatively, the patient developed an infection of the wound which was treated with daily medication. The combination of long-term high dose antibiotic therapy with surgery led to successful treatment.

- Citation: Acquaro P, Tagliabue F, Confalonieri G, Faccioli P, Costa M. Abdominal wall actinomycosis simulating a malignant neoplasm: Case report and review of the literature. World J Gastrointest Surg 2010; 2(7): 247-250

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v2/i7/247.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v2.i7.247

In developed countries, actinomycosis is a relatively rare disease that is mainly caused by Actinomyces israelii. Actinomyces israelii is an anaerobic, gram positive organism that is normally present in the oral cavity, throughout the gastrointestinal tract, female genital tract and the bronchus. Actinomycosis occurs most frequently in the cervical facial (50%-65%), abdominal (20%) and thoracic (15%) regions. The diagnosis is difficult because it can mimic a malignancy. We report on a case of primary abdominal wall actinomycosis and review the literature.

A 47-year-old woman in apparently good health was admitted to the emergency room complaining about a constant non specific lower abdominal pain in the left iliac fossa and hypogastrium for the last month. She had no intestinal or urinary symptoms. Previous medical history included the use of an intrauterine device (IUD). She did not remember either the duration or the date of withdrawal. At admission, the clinical exam revealed a large painless, non pulsatile and fixed mass measuring about 7 cm in diameter in the left iliac fossa and hypogastrium. The laboratory exams revealed mild leucocytosis (WHC) 15 200 cell/L but tumor markers (Carcinoembryonic antigen and carcinoma antigen 125) were within normal range.

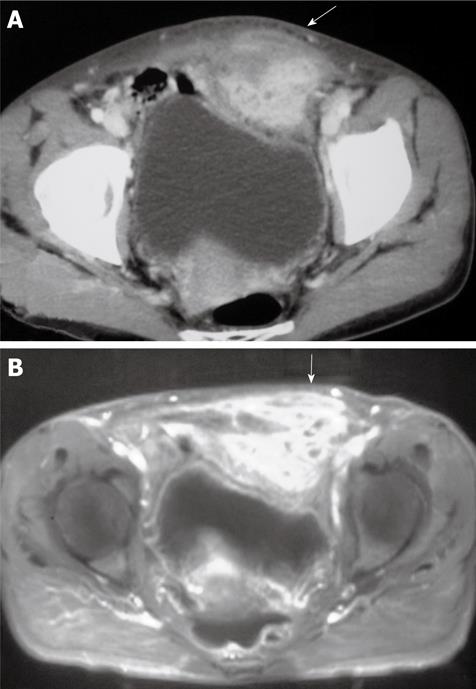

The gynecologic clinical exam revealed no abnormalities. Computed tomography (CT) scan showed the presence of a 6 cm × 5 cm solid mass that originated from the left inferior portion of the rectus muscle of the abdominal wall with prevalent interior growth towards the peritoneal cavity and involvement of the anterior bladder space of Retzius. The anterior left portion of the bladder was compressed without being infiltrated. Inferiorly, the mass extended to the Mount of Venere. The magnetic resonance image (MRI) gave no further information. The diagnostic image suggested that the mass was a muscle neoplasia (Figure 1).

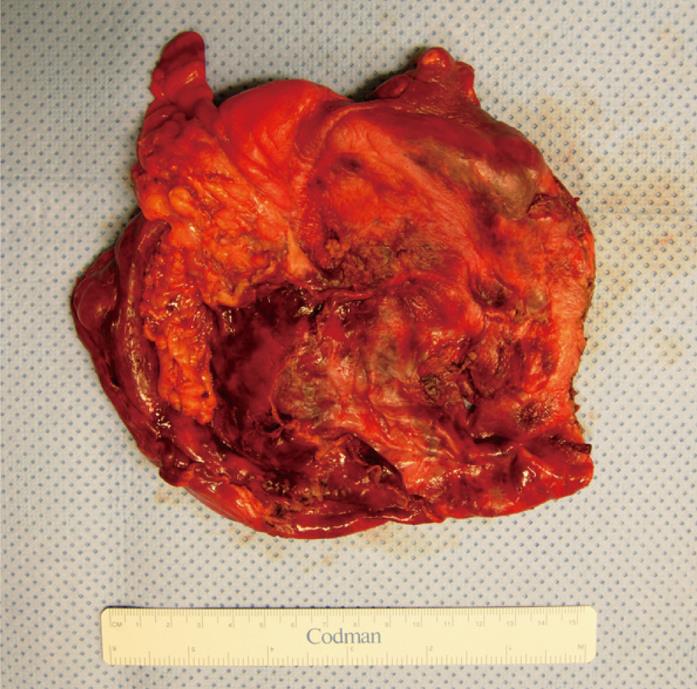

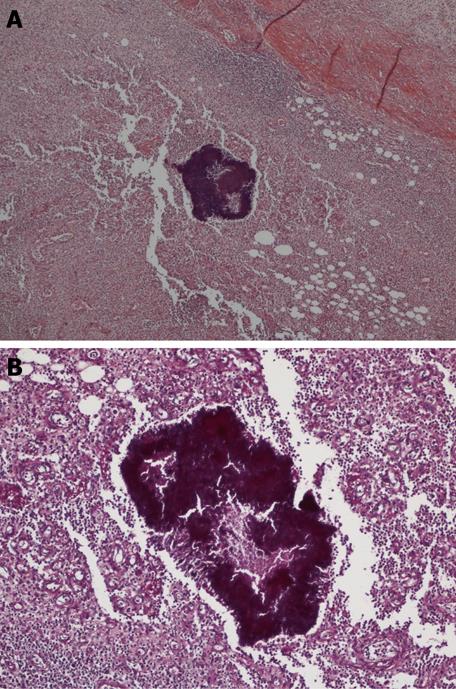

At laparotomy, there was a large mass that originated from the distal portion of the anterior abdominal wall muscle and had dense adhesion to the anterior wall of the urinary bladder, the greater omentum and the sigmoid colon. A careful adhesiolysis was done and the mass isolated with complete excision. Unfortunately, a small portion of the bladder wall was removed en-bloc. The bladder injury was repaired with a re-absorbable continuous suture. To remove the mass, an extensive demolition of the anterior abdominal wall was done; therefore a dual mesh was placed to close the abdominal wall (Figure 2). The histopathological examination showed an extended abscess (6 cm × 8 cm × 3 cm) of the left abdominal rectal muscle with acute inflammation of the serosa of the bladder wall and the parietal peritoneum. In the abscess cavity there was a presence of Actinomyces israelii (Figure 3).

The post-operative recovery was regular except for a wound infection that was treated with daily medication. She had an endovenous antibiotic for 1 wk and then an oral antibiotic for 2 wk.

In developed countries actinomycosis is a rare disease. Actinomycosis is a chronic, supporative pseudotumoral disease caused by an anaerobic gram positive organism which is most frequently Actinomyces israelii. Other species identified that can cause diseases in humans are: A. Bovis, A. Ericksonii, A. Naeslundii, A. Viscosus and A. Odontolyticus[1].

In many cases, abdominal-pelvic actinomycosis is associated with an IUD[2-6]. The manifestation may occur at the time of insertion or withdrawal. However, a review of the literature also reveals some cases of actinomycosis many years after IUD removal.

The presence of actinomycosis in the normal vaginal flora is disputable. Colonization with actinosmyces of the female genital tract is considered rare in women who do not have an IUD[7].

Actinomyces israelii infects 1.65% to 11.6% of IUD users and infection is more common in women who have had an IUD for more than four years[8].

There is no doubt that long-term use of an IUD represents a risk factor for pelvic actinomycosis and potentially for secondary dissemination to a distant site such as in the abdominal wall[7].

Although in the past there were many hypotheses on the pathophysiology of abdomen-pelvic actinomycosis, this is now clearly defined. Actinomyces israelii is considered a saprophyte in various organs of the human body and in particular situations such as a mucosal lesion or low oxygen level it becomes a pathogen[9,10]. This condition allows the penetration of actinomyces through the mucosa and initiates an inflammatory response leading to the formation of pseudotumors and an abscess. The abscess grows slowly and becomes symptomatic when it fistulizes with nearby structures or perforates. In our case, the abscess fistulated into the urinary bladder and omentum. Some predisposing events are: appendicitis, diverticulitis, perforated gastric ulcers, previous bowel surgery, cholecystectomy, pancreatitis, endoscopic manipulation, trauma, immunosuppression and loss of gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy[3,4,9-12].

Actinomycosis abscess can affect the colon, ileum, uterus and tract, liver, abdominal wall, pancreas, greater omentum, retroperitoneum and kidney. In the literature there are not many reports of actinomyces abscess of the abdominal wall. The abdominal wall can be the expression of a primary local infection or secondary to one of the above described events.

Primary abdominal wall localization is rare; up to 2004 only nine cases have been reported in the English medical literature[13,14].

In our case, the patient reported the use of an IUD in the past with no information about how many years she used it or when it was removed.

Independently of its etiology, clinical symptoms are not specific and vary from case to case. A review of literature reveals a wide range of clinical presentation from chronic pseudotumoral to acute abdomen symptoms when complications occur such as perforation and fistulization. In most cases, clinical and diagnostic exams are not able to identify the disease and therefore the treatment becomes complex.

Hematological laboratory exams show elevated non specific inflammatory markers and serology is not diagnostic[4]. CT, ultrasound and MRI are able to confirm the presence of an abscess or pseudotumor mass but not distinguish between neoplasm, endometriosis, pelvic-peritonitis, a bowel inflammatory disease such as Crohn’s disease, sigmoiditis, complicated appendicitis or tuberculosis[2,3].

Pre-operative microbiological culture from a sample is not always possible. Firstly, the clinical presentation of the disease may be acute or the sample can not be obtained with percutaneous methods. Secondly, actinomyces is a gram-positive, slow growing, non-acid-fast, anaerobic, filamentous bacterium that requires specific incubation of fresh material and takes 1 wk to grow[15]. The culture is negative in 76% of cases[2,3]. Therefore, excision biopsy for histopathological examination is frequently needed.

The most difficult task for the management of actinomycosis is to reach a diagnosis before a surgical approach. Preoperative diagnosis is difficult because of non-specific clinical, laboratory and imaging findings. In many cases the diagnosis is during surgical exploration or after extensive and difficult debulking with a high risk of lesion to nearby structures such as the bowel, ureters or bladder. In our case, during surgical removal of the abscess a small bladder lesion and an extensive excision of the rectum muscle were verified.

Diagnosis is provided by anatomopathology illustrating characteristic sulphur granules containing filaments in 50% of the cases[16]. These granules are PAS and Grocott positive.

However, this is not strictly a pathognomonic sign because other species such as Staphylococci, Nocardia, Aspergillus and Streptomyces can also produce sulphur granules[17-19].

Correct preoperative diagnosis is rare. However, if promptly achieved, the gold standard treatment consists of prolonged high-dose intravenous antibiotic therapy, in particular penicillin.

Exclusive antibiotic treatment has been reported to be successful for some cases of pelvic abscesses and abdominal wall lesions[7].

However, in many cases surgery is necessary, especially when the abscess is large or there are some perforative complications such as peritonitis. Similarly, compression on the urinary tract or bowel is an indication for surgical treatment.

Surgery is also necessary when there is no benefit and general health conditions deteriorate after a week of antibiotic treatment or it is not possible to exclude a potential malignancy.

In the presence of a pelvic-abdominal mass, laparoscopy is a less invasive approach that can have a diagnostic and therapeutic function, minimizing the risk of mutilating surgery with better control of the inflammatory infection. However, in selected cases where there is an extensive inflammatory invasion, laparoscopy cannot be applied with safety.

Peer reviewers: Tatsuo Kanda, Assistant Professor, MD, PhD, Division of Digestive and General Surgery, Niigata University, Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Niigata 951-8510, Japan; Lberto Zaniboni, MD, UO di Oncologia, Fondazione Poliambulanza, Via Bissolati 57, Brescia 25124, Italy

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Yang C

| 1. | Hamid D, Baldauf JJ, Cuenin C, Ritter J. Treatment strategy for pelvic actinomycosis: case report and review of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2000;89:197-200. |

| 2. | Sergent F, Marpeau L. Abdominopelvic actinomycosis: a tumoral syndrome due to bacterial infection. J Chir. 2004;14:150-156. |

| 3. | Filipović B, Milinić N, Nikolić G, Ranthelović T. Primary actinomycosis of the anterior abdominal wall: case report and review of the literature. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:517-520. |

| 4. | Das N, Lee J, Madden M, Elliot CS, Bateson P, Gilliland R. A rare case of abdominal actinomycosis presenting as an inflammatory pseudotumour. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:483-484. |

| 5. | Groot G, Rivers L, Smith T, Urbanski P, Boyle C. Abdominal wall actinomycosis associated with use of an intrauterine device: a case report. Can J Surg. 1991;34:450-453. |

| 6. | Pearlman M, Frantz AC, Floyd WS, Faro S. Abdominal wall Actinomyces abscess associated with an intrauterine device. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1991;36:398-402. |

| 7. | Lunca S, Bouras G, Romedea NS, Pertea M. Abdominal wall actinomycosis associated with prolonged use of an intrauterine device: a case report and review of the literature. Int Surg. 2005;90:236-240. |

| 8. | Dogan NU, Salman MC, Gultekin M, Kucukali T, Ayhan A. Bilateral actinomyces abscesses mimicking pelvic malignancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;94:58-59. |

| 9. | Kodali U, Mallavarapu R, Goldberg MJ. Abdominal actinomycosis presenting as lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2003;35:451-453. |

| 10. | Harsch IA, Benninger J, Niedobitek G, Schindler G, Schneider HT, Hahn EG, Nusko G. Abdominal actinomycosis: complication of endoscopic stenting in chronic pancreatitis? Endoscopy. 2001;33:1065-1069. |

| 11. | Yamada H, Kondo S, Kamiya J, Nagino M, Miyachi M, Kanai M, Hayata A, Washizu J, Nimura Y. Computed tomographic demonstration of a fish bone in abdominal actinomycosis: report of a case. Surg Today. 2006;36:187-189. |

| 12. | Ramia JM, Mansilla A, Villar J, Muffak K, Garrote D, Ferron JA. Retroperitoneal actinomycosis due to dropped gallstones. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:345-349. |

| 13. | Khalid K, Qazi SA, Al-Saleh KA. Primary actinomycosis of the abdominal wall. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:229-233. |

| 14. | Owen K, Flannery MT, Elaini AB, Rivera J. Actinomycotic tumor of the abdominal wall. South Med J. 2004;97:175-177. |

| 15. | Nasu K, Matsumoto H, Yoshimatsu J, Miyakawa . Ureteral and sigmoid obstruction caused by pelvic actinomycosis in an Intrauterine Contraceptive Device User. Gyne and obstetric Invest. 2002;54:228-230. |

| 16. | Pitot D, De Moor V, Demetter P, Place S, Gelin M, El Nakadi I. Actinomycotic abscess of the anterior abdominal wall: a case report and literature review. Acta Chir Belg. 2008;108:471-473. |

| 17. | Cintron JR, Del Pino A, Duarte B, Wood D. Abdominal actinomycosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1996;39:105-108. |

| 18. | Weese WC, Smith IM. A study of 57 cases of actinomycosis over a 36-year period. A diagnostic 'failure' with good prognosis after treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1975;135:1562-1568. |

| 19. | Wagenlehner FM, Mohren B, Naber KG, Männl HF. Abdominal actinomycosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:881-885. |