Published online Aug 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i8.109432

Revised: June 3, 2025

Accepted: July 10, 2025

Published online: August 27, 2025

Processing time: 107 Days and 3.6 Hours

In the treatment of rectal cancer, a temporary loop ileostomy (TLI) is created after low anterior resection to protect bowel function in the postoperative period. De

To compare early and late closure of TLIs and demonstrate that early stoma closure can be performed without increasing morbidity.

This study included patients who underwent TLI for rectal cancer, with data collected prospectively between June 2016 and October 2024 and analyzed re

A total of 270 TLIs were created (70.9%). Of these, 120 (44.4%) were closed in the late period (group A), and 150 (55.6%) were closed in the early period (group B). There was no statistically significant difference between group A and group B in terms of demographic and clinicopathological characteristics (P > 0.05). Peri

No statistically significant difference was found between early and late loop ileostomy closure in terms of perioperative and postoperative morbidity. Early closure accelerated patients’ psychological and social recovery.

Core Tip: This retrospective study compares early (group A: 10-14 days) and late (group B: 3-6 months) closure of diverting loop ileostomies (DLI) in patients who underwent surgery for rectal cancer, aiming to demonstrate the feasibility of early stoma closure without increasing morbidity. The results showed no significant differences in morbidity or mortality between the two groups. However, early DLI closure was associated with faster psychological and social recovery in patients.

- Citation: Özcan P, Düzgün Ö. Comparison of complication rates after early and late closure of loop ileostomies: A retrospective cohort study. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(8): 109432

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i8/109432.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i8.109432

In the treatment of rectal cancer, a temporary loop ileostomy (TLI) is created after low anterior resection (LAR) to protect bowel function in the postoperative period. The timing of TLI closure has a significant impact on the patient’s recovery process and the occurrence of complications[1]. Although the role of TLI in preventing anastomotic leakage after colo

In clinical practice, after creation of a TLI, a waiting period of approximately 3-6 months is required until the completion of adjuvant therapy. This waiting period presents significant challenges due to costs, psychosocial distress, and medical complications[4]. In some cases, TLI may become permanent, which can lead to certain patients avoiding surgery or chemotherapy due to the presence of a stoma. Thus, prolonged TLI closure is a concern for patients as it is associated with increased complication rates[5].

In oncological surgical practice, medical oncological treatments like chemotherapy should ideally begin within an average of 3 weeks after surgery. However, in cases where pathology reports are delayed, TLI closure might be considered during this waiting period. It has been reported that early TLI closure may lead to faster recovery and shorter hospital stays, whereas late TLI closure may increase complications due to the impact of the immune system’s recovery process and the potential for prolonged stoma-related issues with delayed closure[6]. In this context, various studies have shown that patients who undergo early TLI closure achieve better outcomes[7,8].

In this study, we compared early (10-14 days) and late (3-6 months) TLI closure in patients undergoing surgery for rectal cancer. The results demonstrated that early TLI closure can be more advantageous for patients by preventing stoma-related complications (e.g., parastomal hernia, dermatitis, and stoma appliance costs) and preserving quality of life (by reducing anxiety and depression), thereby supporting the implementation of early stoma closure in clinical practice.

Patients who underwent surgery for rectal cancer at the Surgical Oncology Clinic of the University of Health Sciences, Ümraniye Training and Research Hospital (Istanbul, Türkiye) between June 2016 and October 2024 were analyzed. Data were evaluated retrospectively. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the University of Health Sciences, Ümraniye Training and Research Hospital (approval No. 2022/366).

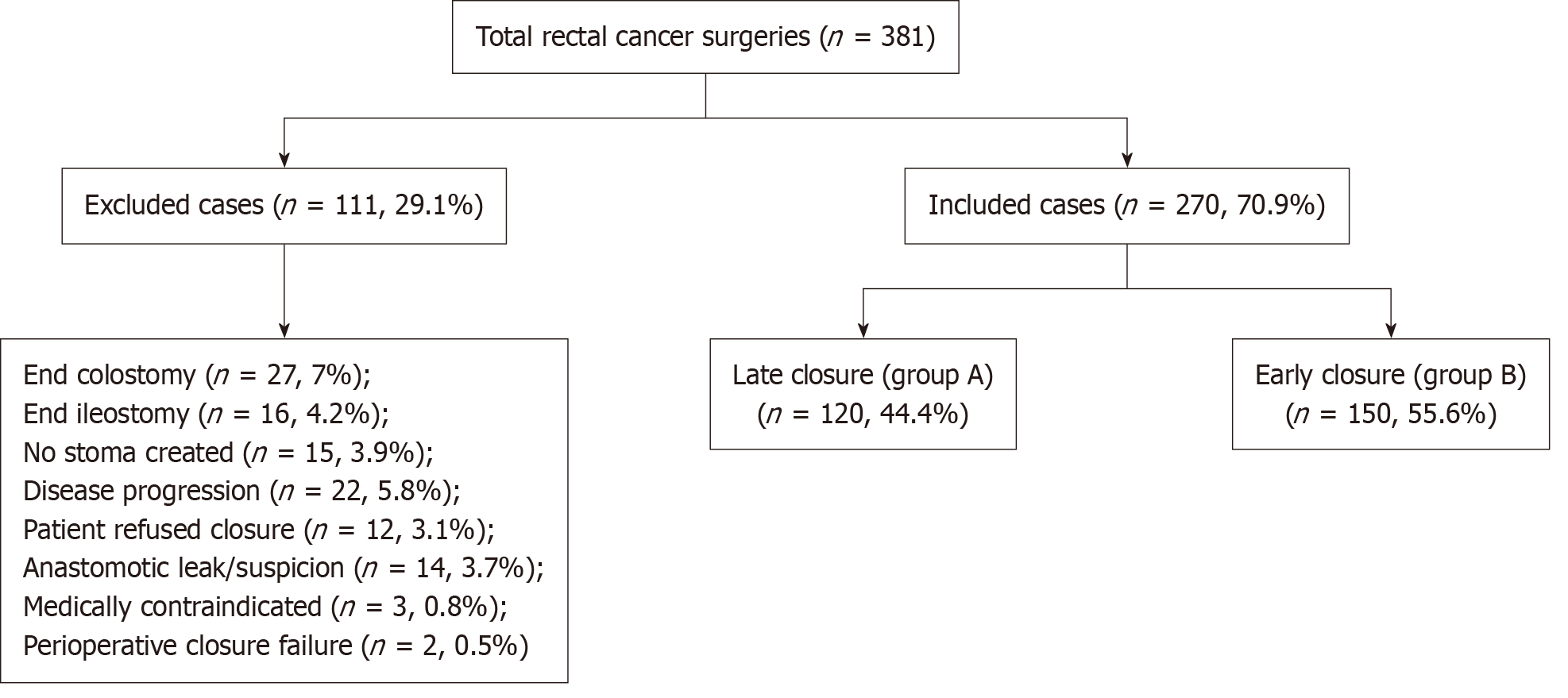

The study included patients over 18 years of age who underwent protective TLI for rectal cancer. The patients were randomly assigned into two separate groups without the application of any selection criteria or risk stratification. Group A (3-6 months) included those who underwent TLI closure between June 2016 and October 2022, and group B (10-14 days) included those who underwent TLI closure between October 2022 and 2024 (Figure 1).

The demographic data of the patients, namely, whether they received neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy, rectoscopic findings, length of hospital stay after rectal surgery, rectosigmoid anastomosis control findings, timing of stoma closure (early vs late), operative time, blood loss, and anastomotic techniques used were analyzed. Additionally, stoma site infec

After the rectal surgery, patients were discharged with a TLI. In group B, stomas were evaluated for closure between days 10 and 14, while in group A, colorectal anastomoses were assessed via rectosigmoidoscopy at 3-6 months after adjuvant therapy. Patients with colorectal anastomotic leakage underwent reoperation for colorectal or coloanal anastomosis. Patients with intact colorectal anastomoses were hospitalized for TLI closure between days 10 and 14.

Surgery was performed under general anesthesia, laryngeal mask anesthesia, or epidural anesthesia. After elliptical incision and stoma dematuration, the ileal segments were mobilized. Side-to-side ileoileal anastomosis was performed using two GIA staplers (MedtronicTM, Mansfield, MA, United States) and the anastomoses were reinforced with 3/0 Vicryl sutures. The fascial layer of tissue was closed using a single, looped No. 1 polydioxanone suture, while the subcutaneous tissue was reinforced with 2/0 Vicryl sutures. No drains were placed in the surgical site. Metal staples were used to close the skin incision, marking the completion of the surgery. Postoperatively, 250 cc of liquid nutrition was initiated at 6 hours. On postoperative day 2, R1 (clear liquid diet) was introduced, followed by R2 (soft-liquid diet) on day 3, and R3 (low-residue solid diet) on days 4 or 5. Patients were planned for discharge after achieving defecation. During follow-ups in the surgical outpatient clinic, the stoma site incisions were monitored through physical examination and reviewing laboratory parameters. For patients in group B, who underwent early closure, postoperative and oncological outcomes were evaluated over a 12-month follow-up period.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Continuous variables were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed continuous variables are presented as the mean ± SD, while non-normally distributed variables are presented as the median and range (minimum-maximum). Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between group A (late stoma closure) and group B (early stoma closure) were conducted using the independent samples t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables, depending on the distribution. The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used for comparison of categorical variables. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Between June 2016 and October 2024, a total of 381 patients underwent surgery for rectal cancer in our clinic. Of these, 27 (7%) had an end colostomy, 16 (4.2%) had an end ileostomy, 15 (3.9%) did not require a stoma, 22 (5.8%) did not undergo stoma closure due to disease progression, 12 (3.1%) refused stoma closure, 14 (3.7%) had anastomotic leakage or suspicion of leakage, 3 (0.8%) had medical contraindications, and 2 (0.5%) could not have their stomas closed intraoperatively. A total of 111 patients (29.1%) were excluded from the study.

The total number of TLIs created was 270 (70.9%), of which 120 (44.4%) were closed in the late period (group A), and 150 (55.6%) were closed in the early period (group B). No significant difference was found between group A and group B in terms of demographic and clinicopathological characteristics (P > 0.05) (Table 1). Although there were more elderly patients and patients with advanced-stage disease in group B, this difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The median time from rectal resection to stoma closure was 11 days (range: 7-14 days) in group B, compared to 164 days (range: 92-493 days) in group A. The extended duration of late stoma closures up to 493 days is attributed to variability in clinical decision-making and patient-related factors. These delays are associated with adjuvant treatments, postoperative complications, and healthcare system limitations. Prolonged stoma duration increases the risk of complications such as parastomal hernia, dehydration, and reduced quality of life, underscoring the importance of individualized patient management and the need to standardize the timing of stoma closure.

| Parameter | 1Group A | 2Group B | P value |

| Patients | 120 (44.4) | 150 (55.6) | |

| Age, mean (range) | 60 (31-80) | 58 (30-77) | > 0.05 |

| Female/male sex | 70 (58.3)/80 (41.7) | 65 (43)/55(57) | > 0.05 |

| Neoadjuvant therapy | 88 (73.3) | 107 (71.3) | > 0.05 |

| Adjuvant therapy | 102 (90) | 140 (93.3) | > 0.05 |

| Rectoscopy | 120 (100) | 150 (100) | |

| Stage of disease | > 0.05 | ||

| 1 | 7 (5.8) | 12 (8) | |

| 2 | 25 (20.8) | 31 (20.6) | |

| 3 | 85 (70.8) | 102 (68) | |

| 4 | 3 (2.5) | 5 (3.4) |

Perioperative findings (anesthesia method, operative time, blood loss, and surgical technique) were similar between the two groups and were not statistically significant (P > 0.05) (Table 2). All anastomoses were performed using the side-to-side ileoileostomy technique with a GIA stapler, and no other surgical technique was used. In both groups, epidural anesthesia, laryngeal mask airway (LMA), or general anesthesia methods were applied. In group B, anesthesia was administered as follows: Epidural in 30 cases (20%), LMA in 101 cases (67.3%), and general anesthesia in 19 cases (12.6%). In group A, the distribution was similar: Epidural in 25 cases (20.8%), LMA in 80 cases (66.6%), and general anesthesia in 15 cases (12.5%). Adhesions were observed in 15 cases (10%) in group B and 10 cases (8.3%) in group A, but the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). The median time to first passage of flatus after surgery was the third postope

| Feature | 1Group A | 2Group B | P value |

| Time to stoma closure in days, mean (range) | 164 (92-493) | 10 (7-14) | < 0.001 |

| Amount of bleeding in mL, mean (range) | 10 (0-200) | 10 (0-150) | > 0.05 |

| Operation time in minutes, mean (range) | 45 (16-58) | 48 (15-60) | > 0.05 |

| Stapler use | 120 (100%) | 150 (100) | |

| Anesthesia type | > 0.05 | ||

| Epidural | 25 (20.8) | 30 (20) | |

| Laryngeal mask | 80 (66.6) | 101 (67.3) | |

| General | 15 (12.5) | 19 (12.6) | |

| Adhesions | 10 (8.3) | 15 (10) | > 0.05 |

| Time to flatus in days, mean (range) | 3 (1-5) | 3 (1-5) | > 0.05 |

| Time to pass feces in days, mean (range) | 5 (4-8) | 4 (3-7) | > 0.05 |

| ICU stay in days | 0 | 0 | |

| Total stay at the hospital after stoma closure in days, mean (range) | 5 (4-24) | 4.4 (3-12) | > 0.05 |

| Readmission | 13 (10.8) | 1 (0.66) | < 0.05 |

According to the Clavien-Dindo complication classification, 2 patients in each group developed abscesses requiring percutaneous drainage under ultrasound guidance. Anastomotic leakage occurred in 3 cases (2.5%) in group A and 4 cases (2.4%) in group B, necessitating reoperation. In group B, 1 patient underwent redo ileoileostomy through the stoma incision, while 3 patients required laparotomy for redo ileoileostomy. In group A, 1 patient underwent redo ileoileostomy through the stoma incision, while 2 patients required laparotomy. Additionally, 1 patient in group A required a new LI (Table 3). There was no statistically significant difference in complication rates as primary outcome between two groups. Quality of life as a secondary outcome was higher in the early closure group and this difference was statistically signi

Readmission due to dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, or acute kidney failure was required in 1 case (0.66%) in group B, compared to 13 cases (10.8%) in group A (P < 0.05). Clavien-Dindo complications were observed in 22 cases (14.3%) in group B and 15 cases (12.4%) in group A, with no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05). No mortality was observed in either group within the first 30 days.

Prolonged hospital stay was observed more frequently in patients of advanced age, those with complications, and particularly in patients with late stoma closure. However, a statistically significant association was only found between prolonged hospital stay and readmission rates (P < 0.05).

Anastomotic leakage following LAR is one of the most severe complications in colorectal surgery, with reported inci

Despite these benefits, TLI can also lead to stoma-related complications such as parastomal hernia, peristomal skin irritation, and dehydration. These physical issues, along with the psychological and financial burdens associated with living with a stoma, can negatively impact patients’ quality of life. Given these concerns, the timing of stoma reversal has become an important subject of clinical research. Recent studies have demonstrated that early TLI closure performed within 10 to 14 days postoperatively is both safe and feasible in carefully selected patients. Moreover, early closure has been shown to significantly reduce the risk of stoma-related complications and decrease the economic impact of pro

In patients with an LI, especially during the early postoperative period, high stoma output frequently leads to signi

The timing of TLI closure is a critical concern for colorectal surgeons, as it significantly influences postoperative recovery, complication rates, and overall quality of life. The standard practice for determining the optimal timing of wound closure timing is typically 4-6 months after the completion of adjuvant oncological treatment, or 2-3 months for those who do not undergo chemotherapy or radiotherapy[5-19]. The standard practice for determining the optimal timing of wound closure after cancer treatment involves a period of recovery from adjuvant treatment, typically 4-6 months after completing chemotherapy or radiation or 2-3 months if no adjuvant therapies were used. Although many patients prefer early TLI closure due to the physical and psychological burden of a stoma, surgeons often delay the procedure until after adjuvant chemotherapy to minimize the risk of anastomotic complications and ensure adequate oncologic surveillance.

Clinical evidence suggests that early TLI closure may confer several advantages. In early closure cases, patients tend to have shorter hospital stays, earlier return to normal activities, and improved psychological outcomes[6-20]. A prospective study by Alves et al[21] of 186 patients reported that ileostomy closure at 8 days post-LAR was associated with reduced postoperative morbidity and shorter hospitalization compared to conventional late closure at 60 days[21]. Similarly, Danielsen et al[22] conducted a multicenter randomized controlled trial (n = 127) and concluded that early TLI closure within 8-13 days postoperatively is safe and feasible in selected patients.

By contrast, late TLI closure is associated with a higher incidence of complications including surgical site infections, anastomotic leakage, and increased technical difficulty due to intra-abdominal adhesions[8]. These adhesions can sig

Despite growing interest in early closure protocols, there is currently no universal consensus regarding the optimal timing. Hussein et al[23] retrospectively analyzed 500 patients with TLI, of whom 455 underwent closure, categorizing them into ≤ 2 months, 2-4 months, and > 4 months post-formation. Their findings showed no statistically significant differences in complication rates, suggesting that closure within 2 months may be feasible and safe in properly selected individuals. Blanco et al[24] also emphasized the safety of early reversal in a cohort of 145 patients, provided that patients are carefully screened for risk factors.

Furthermore, Menegaux et al[25] presented a prospective non-randomized study supporting closure within 10 days postoperatively, while Bakx et al[26] demonstrated that closure within 1-3 weeks could be achieved with low morbidity and no mortality in selected patients. In addition, randomized controlled trials by Lasithiotakis et al[27] and Kłęk et al[28] found that early TLI closure was not associated with higher rates of postoperative complications, further supporting its safety in appropriate cases.

Taken together, the evidence suggests that early TLI closure can lead to positive outcomes when performed on carefully selected patients with adequate clinical and radiological evaluation. However, the decision should remain individualized, taking into account factors such as nutritional status, adjuvant therapy, anastomotic integrity, and patient preference.

However, Bausys et al[29] in their single-center randomized controlled trial comparing early and late closure, found that early closure of TLI within 30 days was neither safe nor feasible in patients with rectal cancer. The authors observed a significantly higher postoperative complication incidence compared to standard closure after 90 days, and serious complications (Clavien-Dindo grade IIIa or higher) were only seen after early TLI closure, leading to early termination of the study. Perez et al[30] recommended that TLI closure should be performed no earlier than 2 months to reduce compli

In our study, we did not observe significant differences between early and late closure in terms of perioperative and postoperative complications. However, we did find that the early closure group experienced a more comfortable psychological and social recovery, as observed with the EORTC QLQ-C30 (version 3). Our results suggest that early TLI closure positively affects patients’ psychological recovery processes and improves quality of life. Additionally, faster physical and psychological recovery allows patients to return to their social lives sooner, improving quality of life and reducing the risk of psychological issues, such as depression, in the postoperative period.

TLI closure presents several challenges, particularly the complications that arise following the procedure. Common complications include anastomotic leaks, strictures, ileus, wound infections, parastomal hernias, electrolyte imbalances, psychological issues requiring support, and difficulties with social integration. Early TLI closure has been associated with a decrease in stoma-related complications such as skin irritation, stoma ulcers, and leakage from the appliance. Additionally, TLI can negatively affect kidney function, especially in elderly patients with hypertension. As a result, reducing the duration of ileostomy use remains a potential advantage for many patients.

Previous randomized controlled trials have shown that in carefully selected patients, TLI can be safely closed within 8 days to 14 days after surgery. In general, if a patient is deemed unsuitable for early closure, it is recommended to postpone until day 90. Sauri et al[31] found no significant differences in postoperative complication rates between early and late closure groups (26.8% vs 22.7%; P = 0.44). The most common complications identified were bowel obstruction and superficial surgical site infections, with a higher rate of superficial infections in the early closure group (11.3% vs 7.7%; P = 0.002). In our study, while we observed a higher rate of wound infections in the early closure group, this difference was not statistically significant.

Williams et al[32] identified bowel obstruction as the most common complication after TLI closure, with the incidence reaching up to 29%. Danielsen et al[22] reported that the early closure group experienced fewer complications than the late closure group, particularly noting that in the 6 month to 12 month range, the late closure group had more serious complications compared to the early group. However, they found no statistically significant difference in the incidence of serious complications (Clavien-Dindo grade IIIa or higher) between the two groups. Tramontano et al[33], in a compara

Alves et al[21] reported that wound infections occurred significantly more frequently in the early period (closure of ileostomy 8 days after ileostomy creation) compared to the late period (closure of ileostomy 60 days after ileostomy creation) (19% vs 5%, respectively; P = 0.007). Fukudome et al[34] in their prospective randomized study of 20 patients, found that the incidence of clinically asymptomatic, radiologically detected colorectal anastomotic leakage was 14.2%, and surgical site infection occurred in 42.8% of the patients. The study was terminated prematurely after 13 patients, and the authors concluded that asymptomatic anastomotic leaks were frequent with a low success rate and high complication rate for early stoma closure within 2 weeks. Therefore, the authors concluded that early stoma closure should not be routinely recommended after LAR. In our study, we detected dissection difficulties in the early period, with rates up to 10%. However, we found that this difficulty was not statistically significant compared to the late period group (P > 0.05).

The main limitation of our study was its retrospective nature, which may lead to selection bias and the absence of randomization. Additionally, there was heterogeneity in treatment protocols, including variations in radiotherapy both short-course and long-course and systemic chemotherapy regimens (e.g., FOLFOX, FOLFIRI, FOLFIRINOX, and the addition of bevacizumab).

In this study, no statistically significant difference was found between early and late closure of TLI regarding peri

| 1. | Snijders HS, Wouters MW, van Leersum NJ, Kolfschoten NE, Henneman D, de Vries AC, Tollenaar RA, Bonsing BA. Meta-analysis of the risk for anastomotic leakage, the postoperative mortality caused by leakage in relation to the overall postoperative mortality. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38:1013-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sherman KL, Wexner SD. Considerations in Stoma Reversal. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017;30:172-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Sarma DR, East J, Zaman S, Mankotia R, Thompson CV, Torrance AW, Peravali R. Meta-analysis of temporary loop ileostomy closure during or after adjuvant chemotherapy following rectal cancer resection: the dilemma remains. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34:1151-1159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Farag S, Rehman S, Sains P, Baig MK, Sajid MS. Early vs delayed closure of loop defunctioning ileostomy in patients undergoing distal colorectal resections: an integrated systematic review and meta-analysis of published randomized controlled trials. Colorectal Dis. 2017;19:1050-1057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ahmadi-Amoli H, Rahimi M, Abedi-Kichi R, Ebrahimian N, Hosseiniasl SM, Hajebi R, Rahimpour E. Early closure compared to late closure of temporary ileostomy in rectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial study. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2023;408:234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mrak K, Uranitsch S, Pedross F, Heuberger A, Klingler A, Jagoditsch M, Weihs D, Eberl T, Tschmelitsch J. Diverting ileostomy versus no diversion after low anterior resection for rectal cancer: A prospective, randomized, multicenter trial. Surgery. 2016;159:1129-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ahmad NZ, Abbas MH, Khan SU, Parvaiz A. A meta-analysis of the role of diverting ileostomy after rectal cancer surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36:445-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee KH, Kim HO, Kim JS, Kim JY. Prospective study on the safety and feasibility of early ileostomy closure 2 weeks after lower anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2019;96:41-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 24843] [Article Influence: 1183.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang L, Chen X, Liao C, Wu Q, Luo H, Yi F, Wei Y, Zhang W. Early versus late closure of temporary ileostomy after rectal cancer surgery: a meta-analysis. Surg Today. 2021;51:463-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cheng Z, Dong S, Bi D, Wang Y, Dai Y, Zhang X. Early Versus Late Preventive Ileostomy Closure Following Colorectal Surgery: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis With Trial Sequential Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Dis Colon Rectum. 2021;64:128-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Podda M, Coccolini F, Gerardi C, Castellini G, Wilson MSJ, Sartelli M, Pacella D, Catena F, Peltrini R, Bracale U, Pisanu A. Early versus delayed defunctioning ileostomy closure after low anterior resection for rectal cancer: a meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of safety and functional outcomes. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2022;37:737-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Emile SH, Horesh N, Garoufalia Z, Gefen R, Ray-Offor E, Wexner SD. Outcomes of Early Versus Standard Closure of Diverting Ileostomy After Proctectomy: Meta-analysis and Meta-regression Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Ann Surg. 2024;279:613-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mirande MD, Bews KA, Brady JT, Colibaseanu DT, Shawki SF, Perry WR, Behm KT, Mathis KL, McKenna NP. Does timing of ileostomy closure impact postoperative morbidity? Colorectal Dis. 2025;27:e70088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Werner JM, Kupke P, Ertl M, Opitz S, Schlitt HJ, Hornung M. Timing of Closure of a Protective Loop-Ileostomy Can Be Crucial for Restoration of a Functional Digestion. Front Surg. 2022;9:821509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gessler B, Haglind E, Angenete E. A temporary loop ileostomy affects renal function. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:1131-1135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Al Khaldi SS, Al Harbi R, Albastaki S, Al Turki N, Ashari L, Alhassan K, Abduljabbar A, Hibbert D, Almughamsi A, Al Homoud S, Alsanea N. Deterioration in renal function after stoma creation: a retrospective review from a Middle Eastern tertiary care center. Ann Saudi Med. 2023;43:76-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vogel I, Shinkwin M, van der Storm SL, Torkington J, A Cornish J, Tanis PJ, Hompes R, Bemelman WA. Overall readmissions and readmissions related to dehydration after creation of an ileostomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech Coloproctol. 2022;26:333-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Matsumoto Y, Aisu N, Kajitani R, Nagano H, Yoshimatsu G, Hasegawa S. Complications associated with loop ileostomy: analysis of risk factors. Tech Coloproctol. 2024;28:60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ayaz-Alkaya S. Overview of psychosocial problems in individuals with stoma: A review of literature. Int Wound J. 2019;16:243-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Alves A, Panis Y, Lelong B, Dousset B, Benoist S, Vicaut E. Randomized clinical trial of early versus delayed temporary stoma closure after proctectomy. Br J Surg. 2008;95:693-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Danielsen AK, Park J, Jansen JE, Bock D, Skullman S, Wedin A, Marinez AC, Haglind E, Angenete E, Rosenberg J. Early Closure of a Temporary Ileostomy in Patients With Rectal Cancer: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2017;265:284-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hussein NL, Stevenson AP, Lawton CF, Elmayan A, Hillis EE, Burton JH, Fuhrman G. An Analysis of the Timing for Closure of a Diverting Loop Ileostomy. Am Surg. 2023;89:3870-3872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Blanco Terés L, Cerdán Santacruz C, Correa Bonito A, Delgado Búrdalo L, Rodríguez Sánchez A, Bermejo Marcos E, García Septiem J, Martín Pérez E. Early diverting stoma closure is feasible and safe: results from a before-and-after study on the implementation of an early closure protocol at a tertiary referral center. Tech Coloproctol. 2024;28:32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Menegaux F, Jordi-Galais P, Turrin N, Chigot JP. Closure of small bowel stomas on postoperative day 10. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:713-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bakx R, Busch OR, van Geldere D, Bemelman WA, Slors JF, van Lanschot JJ. Feasibility of early closure of loop ileostomies: a pilot study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:1680-1684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lasithiotakis K, Aghahoseini A, Alexander D. Is Early Reversal of Defunctioning Ileostomy a Shorter, Easier and Less Expensive Operation? World J Surg. 2016;40:1737-1740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kłęk S, Pisarska M, Milian-Ciesielska K, Cegielny T, Choruz R, Sałówka J, Szybinski P, Pędziwiatr M. Early closure of the protective ileostomy after rectal resection should become part of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocol: a randomized, prospective, two-center clinical trial. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2018;13:435-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bausys A, Kuliavas J, Dulskas A, Kryzauskas M, Pauza K, Kilius A, Rudinskaite G, Sangaila E, Bausys R, Stratilatovas E. Early versus standard closure of temporary ileostomy in patients with rectal cancer: A randomized controlled trial. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120:294-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Perez RO, Habr-Gama A, Seid VE, Proscurshim I, Sousa AH Jr, Kiss DR, Linhares M, Sapucahy M, Gama-Rodrigues J. Loop ileostomy morbidity: timing of closure matters. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1539-1545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sauri F, Sakr A, Kim HS, Alessa M, Torky R, Zakarneh E, Yang SY, Kim NK. Does the timing of protective ileostomy closure post-low anterior resection have an impact on the outcome? A retrospective study. Asian J Surg. 2021;44:374-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Williams L, Armstrong MJ, Finan P, Sagar P, Burke D. The effect of faecal diversion on human ileum. Gut. 2007;56:796-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Tramontano S, Sarno G, Iacone B, Luciano A, Giordano A, Bracale U. Early versus late closure of protective loop ileostomy: functional significant results in a preliminary analysis. Minerva Surg. 2024;79:435-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Fukudome I, Maeda H, Okamoto K, Yamaguchi S, Fujisawa K, Shiga M, Dabanaka K, Kobayashi M, Namikawa T, Hanazaki K. Early stoma closure after low anterior resection is not recommended due to postoperative complications and asymptomatic anastomotic leakage. Sci Rep. 2023;13:6472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |