Published online Aug 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i8.107558

Revised: April 23, 2025

Accepted: June 23, 2025

Published online: August 27, 2025

Processing time: 153 Days and 0.6 Hours

An inflammatory fibrotic polyp (IFP) of the gastrointestinal tract is generally considered benign and noninvasive. An IFP in the duodenum is very rare. Here we report the case of an aggressive and infiltrative duodenal IFP resembling a malignancy and the patient subsequently underwent surgery. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of duodenal IFP invading the subserosa.

A 50-year-old female patient presented with recurrent epigastric pain for more than 1 month. Gastroscopy revealed a mass in the duodenal bulb involving the pylorus. Endoscopic ultrasound suggested that the lesion was a hypoechoic mass involving the muscularis propria, and duodenal bulb stromal tumor was con

This duodenal IFP invading subserosa indicates that IFP has specific invasion characteristics, and accurate diagnosis is critical to avoid inadequate treatment.

Core Tip: An inflammatory fibrotic polyp (IFP) of the gastrointestinal tract is generally considered benign and noninvasive. An IFP in the duodenum is very rare. Here we report the case of a mass in the duodenal bulb involving the pylorus. Based on imaging and endoscopic findings, a duodenal stromal tumor was considered. The patient underwent surgery, with a pathologic diagnosis of duodenal IFP and tumor invasion of the subserosa, which indicated that IFP is also specifically invasive. Due to the special location of duodenal IFP, accurate diagnosis should be made so as to avoid excessive surgical treatment.

- Citation: Zhang FM, Ning LG, Wang JJ, Zhu HT, Feng MB, Chen HT. Invasive inflammatory fibrotic polyp of the duodenum: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(8): 107558

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i8/107558.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i8.107558

Inflammatory fibrotic polyp (IFP) is a rare gastrointestinal polypoid lesion. Recent studies have confirmed that IFP is not an inflammatory response, but has a tumorous nature[1]. Its pathogenesis remains unclear. Pathologically, it is characterized by the specific arrangement of fibrous tissue and vascular infiltration, as well as eosinophil infiltration. At present, IFP is considered a benign tumor, and there are no reports of malignant transition. However, a recent study has also reported a case in which a gastric IFP invaded the muscularis propria and extended to the subserosa, suggesting that IFP may have invasive potential. IFP usually occurs in the stomach, but can occur throughout the gastrointestinal tract. A duodenal IFP is very rare. Here, we report a case of duodenal IFP located in the duodenal bulb involving the pylorus, which resembled a malignant lesion based on both morphological and radiographic findings.

Repeated upper abdominal pain for more than a month.

One month ago, the patient experienced upper abdominal pain, accompanied by abdominal distension and loss of appetite, without radiating back pain, nausea, vomiting, chest tightness, black stool or diarrhea. A gastroscopy at a local hospital identified a mass in the duodenal bulb involving the pylorus. Pathological examination showed necrotic tissue, a small amount of fibrous tissue, and inflammatory cell infiltration with degeneration and necrosis in the fibrous tissue.

The patient had no history of hypertension, diabetes, or other major organ diseases such as cardiopulmonary disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, etc.

There was no significant personal or family history.

Physical examinations revealed no obvious abnormalities.

Laboratory tests, including complete blood count, biochemistry, tumor markers, stool occult blood examination, etc., showed no abnormalities.

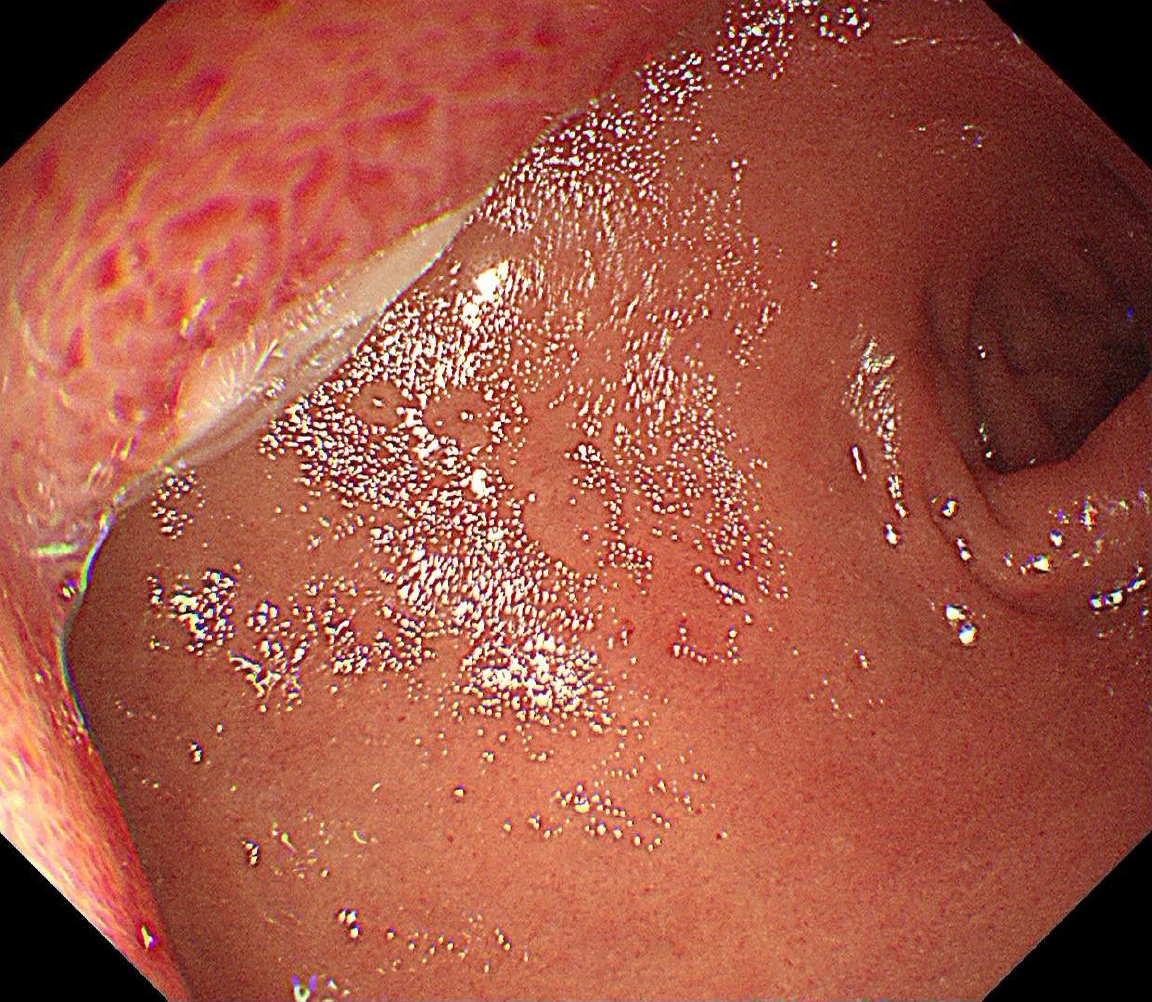

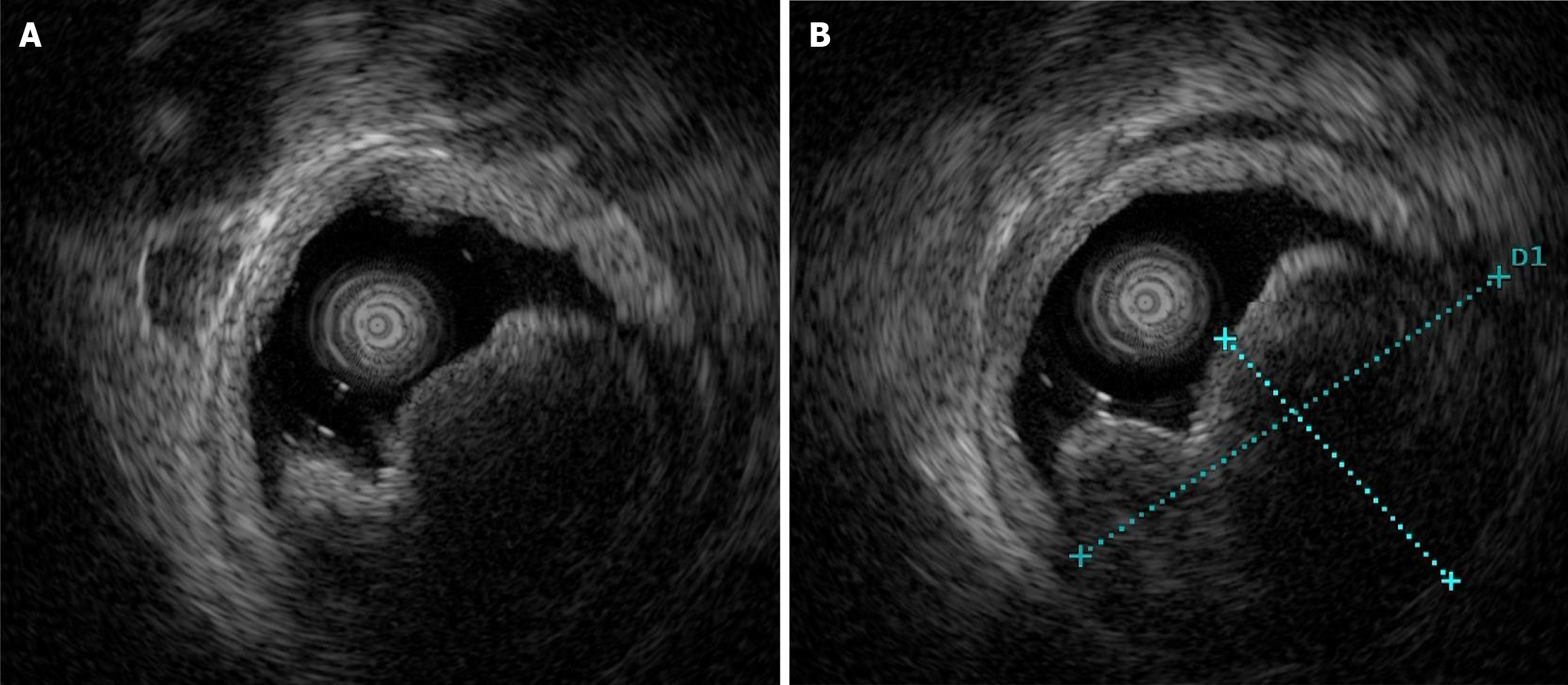

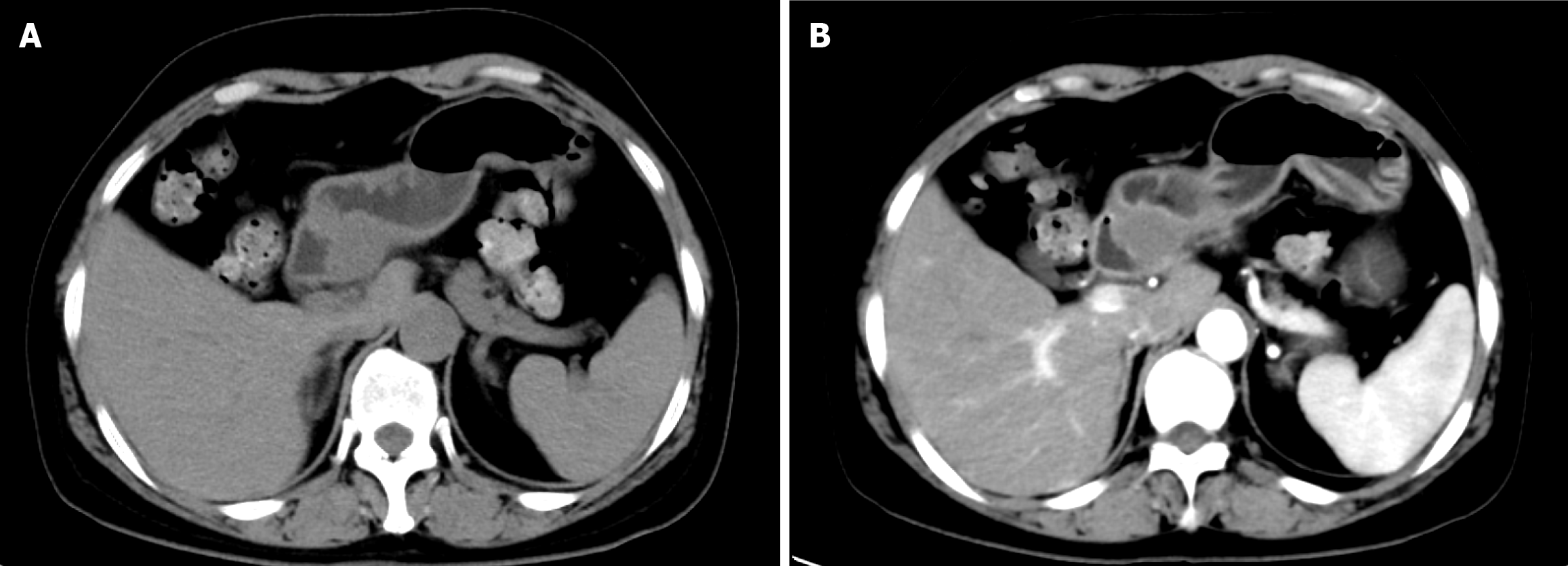

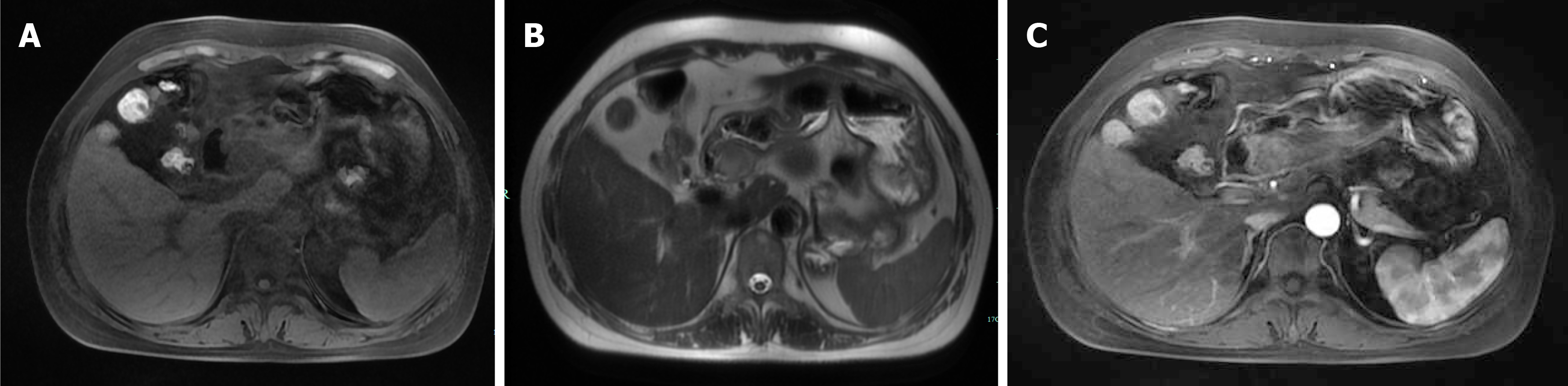

Gastroscopy showed a mucosal bulge in the duodenal bulb involving the pylorus, and the surface of the lesion was congested (Figure 1). Pathological results of the biopsy tissue showed mucosal ulcers and mild spindle cell hyperplasia beside the necrotic tissue, thus, a tumor could not be excluded. The source was not indicated due to minimal tissue in the immunohistochemistry sections. Ultrasonography (12 MHz) was able to demonstrate that the lesion was a hypoechoic mass, the normal hierarchy had disappeared and was replaced by a hypoechoic uniform structure which involved the muscularis propria, and the serosal layer was basically complete (Figure 2A). The lesion was approximately 37.1 mm × 24.5 mm in size (Figure 2B). Computed tomography (CT) revealed an oval lesion with a clear border, which grew into the lumen and showed soft tissue density during plain scan with CT values of 37 HU (Figure 3A). The lesion showed moderate sustained enhancement during the enhanced scanning period, with CT values of 48 HU during the arterial phase (Figure 3B). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed an oval lesion with a clear edge in the duodenal bulb, showing a high signal on T2 weighted imaging (T2WI; Figure 4A) and an equal signal on T1 weighted imaging (T1WI; Figure 4B). Following enhancement, the lesion showed significant enhancement, with foci of low signal internally (Figure 4C).

Based on the clinical history, CT and MRI findings, gastroscopy and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) features and pathological results, the patient was diagnosed with a duodenal stromal tumor.

After full communication with the patient and her family members, surgical treatment was suggested. Intraoperative exploration revealed that the mass was located in the duodenal bulb (gastroduodenal junction), was approximately 30 mm × 30 mm in size, the serosal surface was not significantly pale, several lymph nodes were visible around the stomach, and no obvious metastatic lesions were found. The intraoperative frozen pathology results suggested that the origin was non-gastrointestinal epithelium, and the upper and lower resection margins were negative. Laparoscopic distal gastrectomy + D1 lymph node dissection + gastrojejunostomy (Billroth II) + Braun enteric anastomosis were performed. Postoperatively, electrocardiographic monitoring was given, the patient was put on a fasting diet, and fluid replacement was carried out. Esomeprazole sodium injection at a dose of 40 mg twice a day was administered to protect the stomach, and Cefuroxime at a dose of 1.5 g twice a day was administered intravenously for anti-infection treatment.

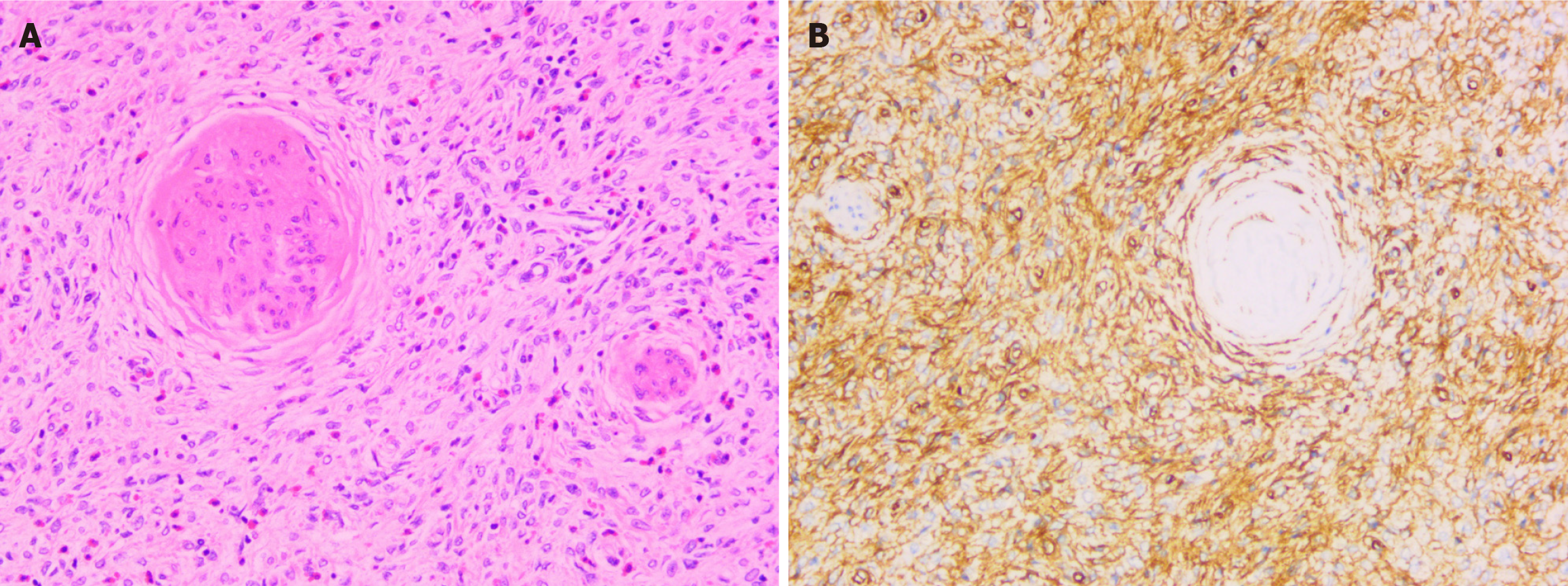

The patient's operation was uneventful without complications. Postoperatively, the patient's vital signs, including body temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, and respiration rate, were stable. The surgical wound showed no signs of infection, bleeding, or exudation, and the patient had no uncomfortable symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or abdominal distension. Five days after surgery, the patient was discharged. The pathological results of the distal gastrectomy specimen showed that the duodenal mass involved the pylorus and was approximately 38 mm × 32 mm × 28 mm in size. The surface mucosa was smooth, and the section was gray-white and yellow with a soft texture. Pathology of the surgical specimens showed that the tumor cells were spindle, polygonal, arranged in bundles, mixed with eosinophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells, with rare nuclear mitoses, and involved the subserosa (Figure 5A). Immunohistochemical staining revealed diffuse strongly positive CD34 with proliferating spindle cells growing "onion-skin-like" around small vessels (Figure 5B), focally positive for smooth muscle actin (SMA) and Cyclin D1, negative for CD117, and discovered on GIST-1 (DOG-1), S100 protein, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). The Ki-67 proliferation index in the lesion cells was 3%. The pathologist suggested that platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α (PDGFR-α) gene testing was feasible if necessary. The patient refused the PDGFR-α genetic testing because it was expensive. Eight months after surgery, gastroscopy revealed residual gastritis and anastomostomatitis, with no lesion recurrence. The patient recovered well after surgery and had no recurrence at the 27-month follow-up. The timeline information in this case is presented in Table 1.

| Time | Event |

| July 2, 2022 | Visit the outpatient department |

| July 7, 2022 | Endoscopic ultrasonography examination |

| July 12, 2022 | Enhanced abdominal computed tomography examination |

| July 13, 2022 | Gastric magnetic resonance imaging examination |

| July 14, 2022 | Admission to hospital, gastroscopy examination |

| July 20, 2022 | The pathological result of the gastroscopy is reported back |

| July 23, 2022 | Surgery |

| July 28, 2022 | The pathological result of the operation is reported back |

| August 1, 2022 | Discharge |

| March 27, 2023 | Have a follow-up gastroscopy examination |

IFP was first described in 1949 by Vanek[1] and was once called "gastrointestinal submucosal granuloma with eosinophilic infiltration". There is a debate regarding whether IFP is a true neoplastic lesion, and many scholars have proposed hypotheses. However, after the discovery of frequent activating mutations in the exons 12 and 18 of the PDGFR-α gene in IFP, the neoplastic nature of IFP was clarified[2]. Subsequent research has also confirmed this finding[3-6]. Besides, there are some reports of recurrent and familial IFP supporting a genetic background[7,8].

Macroscopically, IFPs originate from the mucosa and submucosa, mainly characterized by vascular and fibroblast proliferation with an inflammatory response, mainly eosinophil infiltration. Spindle cells often form a whirlpool-like arrangement around blood vessels, known as the characteristic "onion-skin" change[9,10]. Immunohistochemically, IFPs are always positive for vimentin, CD34, and SMA and negative for CD117, Bcl-2, DOG-1, Desmin, S-100, creatine kinase, neuron-specific enolase, factor VIII, and ALK[9,11]. In this case, tumor cells were spindle, polygonal, and arranged in bundles, mixed with eosinophils, lymphocytes and plasma cells, with rare nuclear mitoses, and involved the subserosa. Immunohistochemical staining revealed diffuse strongly positive for CD34 with proliferating spindle cells growing "onion-skin-like" around small vessels, focally positive for SMA and Cyclin D1, and negative for CD117, DOG-1, S100 protein, and ALK. The Ki-67 proliferation index in the lesion cells was 3%.

IFP is mainly found in the stomach, most commonly in the gastric antrum and rarely in the duodenum. A review of IFPs in the small intestine showed that the most common site for IFP in the small intestine was the ileum (77.9%), followed by the jejunum (13%) and least in the duodenum (6.5%)[12]. In 2022, Yi et al[13] summarized 12 cases of duodenal IFP reported in the literature (incomplete clinical data in some cases) and found that 6 cases were elderly patients, 2 were children with age of onset ranging from 3 to 66 years, median age was 52.5 years, and 4 females and 3 males. Three IFPs were in the duodenal bulb, one in the descending part and three at the level of the duodenum. There were polyps in five cases and a mass in four cases. All IFPs were single, and had a maximum diameter of 1.25-12.5 cm. Patients with duodenal IFPs are usually asymptomatic or are accidentally found during endoscopy or laparotomy procedures performed for other reasons. Some present with non-specific features of abdominal pain or upper gastrointestinal blood loss. Other symptoms, such as chronic diarrhea, vomiting, alterations in bowel habits, or weight loss, are less frequent[14,15]. In the present case, the patient was admitted to hospital due to epigastric pain for more than 1 month. The lesion was located in the duodenal bulb and showed a mass-like appearance under gastroscopy. EUS showed a hypoechoic mass, the normal hierarchy had disappeared and was replaced by a hypoechoic uniform structure involving the muscularis propria, the serosal layer was basically complete, and the tumor was approximately 37.1 mm × 24.5 mm.

The relevant radiological literature on duodenal IFP is limited. A study analyzed the CT findings of 14 cases of IFP, and found that 13 IFPs were round, oval or polypoid, and one was irregular, 12 had indistinct margins and 2 had clear margins, and all the lesions grew into the lumen. There were little calcification, cysts, and bleeding inside the lesion. All lesions presented as slightly hypodense on plain scan, with a CT value of 18.42 ± 3.65 HU. The lesions showed moderate and continuous enhancement following enhanced CT and that the density gradually became uniform over time. CT values at the arterial, venous, and delayed stages were 28.27 ± 5.28 HU, 41.56 ± 7.47 HU, and 50.26 ± 6.78 HU, respectively[16,17]. In our case, CT revealed an oval lesion with a clear border, which had grown into the lumen and showed soft tissue density during a plain scan with CT values of 37 HU; the lesion showed moderate sustained enhancement in the enhanced scanning period, with CT values of 48 HU and 70 HU during the arterial and venous phases, respectively. There are few reports on the MRI findings in IFP. Righetti et al[18] shared a case of duodenal IFP in a 3-year-old patient, and abdominal MRI detected homogeneous enhancement of the mass after contrast administration. In our case, MRI revealed an oval lesion with clear edges in the duodenal bulb, which showed a high signal on T2WI and an isointense signal on T1WI. Following enhancement, the lesion was significantly enhanced with foci of low signal internally.

IFP of the gastrointestinal tract typically presents as a solitary polypoid or sessile intramural lesion under endoscopy, with a smooth or eroded mucosal surface[19-21]. One case of invasive IFP of the stomach reported by Harima et al[22] showed a relatively large submucosal elevated lesion under endoscopy, the mucosal surface was congested and accompanied by granular changes, and it was located at the prepyloric antrum, causing obstruction of the gastric outlet. Histopathological examination revealed the tumor extended to the subserosal layer. Kawai et al[23] reported a case of gastric IFP located at the fornix of the stomach. Endoscopy revealed a polypoid lesion consisting of irregular ridges with ulceration there. Histopathological examination revealed the lesion was located in the submucosal layer. The lesion in our case was located in the duodenal bulb and showed a mass-like appearance under gastroscopy, and histopathological examination revealed that the tumor involved the subserosal layer. These three cases of invasive IFP did not present with the conventional endoscopic manifestations. The possible reasons for these special endoscopic manifestations are as follows. Tumor cells have proliferative and invasive characteristics, and they may break through the original tissue layers and grow towards the surrounding or deeper tissues. Growing downward and involving the subserosal layer is a manifestation of its invasiveness, which is in line with the general laws of tumor growth and invasion. Different origins may lead to differences in their clinical manifestations and growth patterns. For example, IFP originating from the deep submucosal tissue is more likely to grow towards the subserosal layer, while IFP originating from the deep mucosa may preferentially grow towards the mucosal and submucosal layers. Factors such as the patient's immune status, underlying diseases, and the local microenvironment of the gastrointestinal tract may all have an impact on the growth and invasiveness of IFP. However, it is necessary to conduct a comprehensive analysis and clarify the exact causes by in-depth pathological studies, genetic testing, and other means.

Previous researchers summarized the EUS characteristics of 10 cases of gastric IFP, and found that the most common EUS features were an indistinct margin and a hypoechoic, homogeneous echo pattern[24]. Some IFPs also present as medium-low-echo, medium-high-echo or low echo lesions with high echo areas, with heterogeneous echo and distinct margins[24,25]. In the present case, EUS demonstrated that the lesion was a hypoechoic mass, that the normal hierarchy had disappeared and was replaced by a hypoechoic uniform structure involving the muscularis propria, and the serosal layer was basically complete, which suggests that the appearance of duodenal IFP under EUS is diverse.

In order to relieve symptoms and resolve diagnostic uncertainty, complete resection is the treatment of choice for IFPs. Endoscopic polypectomy is the ideal technique if the lesion is polypoidal and accessible, as is usually the case in the stomach and colon. Duodenal IFP is very rare. Of the 12 cases of duodenal IFP summarized in the literature[13], 2 cases underwent partial bowel resection, 3 cases underwent EUS mass resection, 1 case underwent mass resection by laparotomy, another case underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy due to unclear preoperative diagnosis, and all cases had good postoperative recovery and no recurrence during follow-up. In our case, based on the clinical history, CT and MRI findings, gastroscopy and EUS features, and pathological results, the possibility of malignancy could not be ruled out. Therefore, surgical treatment was performed and there was no recurrence eight months after surgery. IFPs of the gastrointestinal tract are generally considered benign and rarely recur or metastasize. However, if they are not completely resected, there is a risk of recurrence[26].

This is the first reported case of duodenal IFP with subserosal involvement. According to the findings of CT, MRI, gastroscopy, and EUS before surgery, the possibility of duodenal stromal tumor could not be completely excluded. Therefore, the patient underwent surgery, and the pathological result after the surgery confirmed the diagnosis of duodenal IFP. Duodenal IFP is extremely rare. Under endoscopy, it often presents as a solitary polypoid or sessile, intramural lesion. However, its endoscopic manifestations are atypical, which increase the uncertainty of diagnosis or misleads clinicians. The duodenum has a special location, and surgery may sometimes lead to complications, having a significant impact on the patient. Endoscopists need to enhance their understanding of IFP. When the pathological results after endoscopic biopsy do not suggest malignancy, deep biopsy or EUS-guided puncture can be used to further clarify the diagnosis. Although the surgery for this patient was successful, there were no obvious postoperative complications, and the patient was in good condition during the follow-up period, it would have been better if other means were attempted preoperatively to further confirm the diagnosis.

We present the first case report of an invasive duodenal IFP. Based on the present case, IFP may be considered not only neoplastic but also potentially invasive. Due to the special location of duodenal IFP, accurate understanding of duodenal IFP and its invasive characteristics is critical to avoid inadequate treatment.

We sincerely appreciate the patients and their families for their cooperation in information acquisition, treatment, and follow-up.

| 1. | Vanek J. Gastric submucosal granuloma with eosinophilic infiltration. Am J Pathol. 1949;25:397-411. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Schildhaus HU, Cavlar T, Binot E, Büttner R, Wardelmann E, Merkelbach-Bruse S. Inflammatory fibroid polyps harbour mutations in the platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRA) gene. J Pathol. 2008;216:176-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Schildhaus HU, Büttner R, Binot E, Merkelbach-Bruse S, Wardelmann E. [Inflammatory fibroid polyps are true neoplasms with PDGFRA mutations]. Pathologe. 2009;30 Suppl 2:117-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lasota J, Wang ZF, Sobin LH, Miettinen M. Gain-of-function PDGFRA mutations, earlier reported in gastrointestinal stromal tumors, are common in small intestinal inflammatory fibroid polyps. A study of 60 cases. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:1049-1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yamashita K, Arimura Y, Tanuma T, Endo T, Hasegawa T, Shinomura Y. Pattern of growth of a gastric inflammatory fibroid polyp with PDGFRA overexpression. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E171-E172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Daum O, Hatlova J, Mandys V, Grossmann P, Mukensnabl P, Benes Z, Michal M. Comparison of morphological, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic features of inflammatory fibroid polyps (Vanek's tumors). Virchows Arch. 2010;456:491-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Anthony PP, Morris DS, Vowles KD. Multiple and recurrent inflammatory fibroid polyps in three generations of a Devon family: a new syndrome. Gut. 1984;25:854-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Allibone RO, Nanson JK, Anthony PP. Multiple and recurrent inflammatory fibroid polyps in a Devon family ('Devon polyposis syndrome'): an update. Gut. 1992;33:1004-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu TC, Lin MT, Montgomery EA, Singhi AD. Inflammatory fibroid polyps of the gastrointestinal tract: spectrum of clinical, morphologic, and immunohistochemistry features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:586-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pantanowitz L, Antonioli DA, Pinkus GS, Shahsafaei A, Odze RD. Inflammatory fibroid polyps of the gastrointestinal tract: evidence for a dendritic cell origin. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:107-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Unal Kocabey D, Cakir E, Dirilenoglu F, Bolat Kucukzeybek B, Ekinci N, Akder Sari A. Analysis of clinical and pathological findings in inflammatory fibroid polyps of the gastrointestinal system: A series of 69 cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2018;37:47-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ivaniš N, Tomas V, Vranić L, Lovasić F, Ivaniš V, Žulj M, Šuke R, Štimac D. Inflammatory Fibroid Polyp of the Small Intestine: A Case Report and Systematic Literature Review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2020;29:455-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yi L, Wang C, Zhang Q, Hao ZF, Wang J, Wu WX, Zhang XH. [Inflammatory fibroid polyp of duodenum:report of a case and review of literature]. Zhenduan Binglixue Zazhi. 2022;4:331-335. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Nerli RB, Jali SM, Guntaka AK, Malur PR, Anita B, Hiremath MB. Giant inflammatory fibroid polyp of the terminal ileum presenting with lower urinary tract symptoms: Case report. Indian J Cancer. 2014;51:541-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | El Hajj II, Sharara AI. Jejunojejunal intussusception caused by an inflammatory fibroid polyp. Case report and review of the literature. J Med Liban. 2007;55:108-111. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Liang XH, Chai YJ, Zhou Q, Ke XA, Han L, Zhou JL. [CT findings of gastrointestinal in flammatory fibrous polyps]. Zhongguo Yixue Yingxiang Jishu. 2019;35:312-314. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Liang XH, Zhou Q, Ke XA, Han L, Zhou JL. [Comparison on CT signs of gastric stromal tumor and inflammatory fibrous polyp]. Zhongguo Yixue Yingxiang Jishu. 2019;35:376-380. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Righetti L, Parolini F, Cengia P, Boroni G, Cheli M, Sonzogni A, Alberti D. Inflammatory fibroid polyps in children: A new case report and a systematic review of the pediatric literature. World J Clin Pediatr. 2015;4:160-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wysocki AP, Taylor G, Windsor JA. Inflammatory fibroid polyps of the duodenum: a review of the literature. Dig Surg. 2007;24:162-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Akbulut S. Intussusception due to inflammatory fibroid polyp: a case report and comprehensive literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5745-5752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Morales-Fuentes GA, de Ariño-Suárez M, Zárate-Osorno A, Rodríguez-Jerkov J, Terrazas-Espitia F, Pérez-Manauta J. Vanek's polyp or inflammatory fibroid polyp. Case report and review of the literature. Cir Cir. 2011;79:242-245, 263. [PubMed] |

| 22. | 22 Harima H, Kimura T, Hamabe K, Hisano F, Matsuzaki Y, Sanuki K, Itoh T, Tada K, Sakaida I. Invasive inflammatory fibroid polyp of the stomach: a case report and literature review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kawai A, Matsumoto H, Haruma K, Kanzaki T, Sugawara Y, Akiyama T, Hirai T. Rare case of gastric inflammatory fibroid polyp located at the fornix of the stomach and mimicking gastric cancer: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2020;6:292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Matsushita M, Hajiro K, Okazaki K, Takakuwa H. Gastric inflammatory fibroid polyps: endoscopic ultrasonographic analysis in comparison with the histology. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:53-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Aydin A, Tekin F, Gunsar F, Tuncyurek M. Gastric inflammatory fibroid polyp. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:802-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zinkiewicz K, Zgodzinski W, Dabrowski A, Szumilo J, Cwik G, Wallner G. Recurrent inflammatory fibroid polyp of cardia: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:767-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |