Published online Jul 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i7.107046

Revised: April 24, 2025

Accepted: May 28, 2025

Published online: July 27, 2025

Processing time: 131 Days and 23.7 Hours

Emphysematous gastritis (EG) is a rare and serious condition that has fatal consequences. Although its clinical presentation is not specific, radiological ima

An 88-year-old male with multiple comorbidities presented to our center with abdominal pain and increased stoma output as chief complaints. Upon further investigation he was found to have EG. Despite the high mortality risk without intervention, the patient and family declined operative intervention.

This case report underscored the challenges of managing a critically ill elderly patient with a history of multiple comorbidities and extensive abdominal sur

Core Tip: Emphysematous gastritis is a rare gastrointestinal emergency that can be life-threatening. It occurs when gas accumulates in the stomach wall due to gas-producing bacteria or ischemia. The patient reported in this case received successful non-surgical management despite having multiple health comorbidities and a history of several abdominal surgeries, reflecting the high mortality risk associated with emphysematous gastritis. This medical presentation underscored the importance of early diagnosis and demonstrated how non-operative therapy can be advantageous for elderly patients who are high risk.

- Citation: Alshahwan N, Alqarzaie AA, Aldeligan SH, Alqusiyer AA, Alnumay A, Mashbari H, Alkanhal A. Successful conservative management of emphysematous gastritis in an elderly patient with multiple comorbidities: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(7): 107046

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i7/107046.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i7.107046

In the English medical literature, there have only been less than 100 reported cases of emphysematous gastritis (EG), which is a severe and rare form of gastritis characterized by the presence of intramural gas in the gastric wall produced by gas-forming organisms[1]. This condition was first introduced in 1889 by Eug Fraenkel who named it “gastritis acuta emphysematosa”[2]. Clinical presentation of this condition is not specific but typically presents with abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and hematemesis. Predisposing risks include comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, renal failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) usage, recent abdominal surgery, alcohol, and gastric ulcers[2,3]. This disease entity has a significant risk of mortality of up to 60%[1]. Therefore, a high suspicious index is important for prompt detection and management.

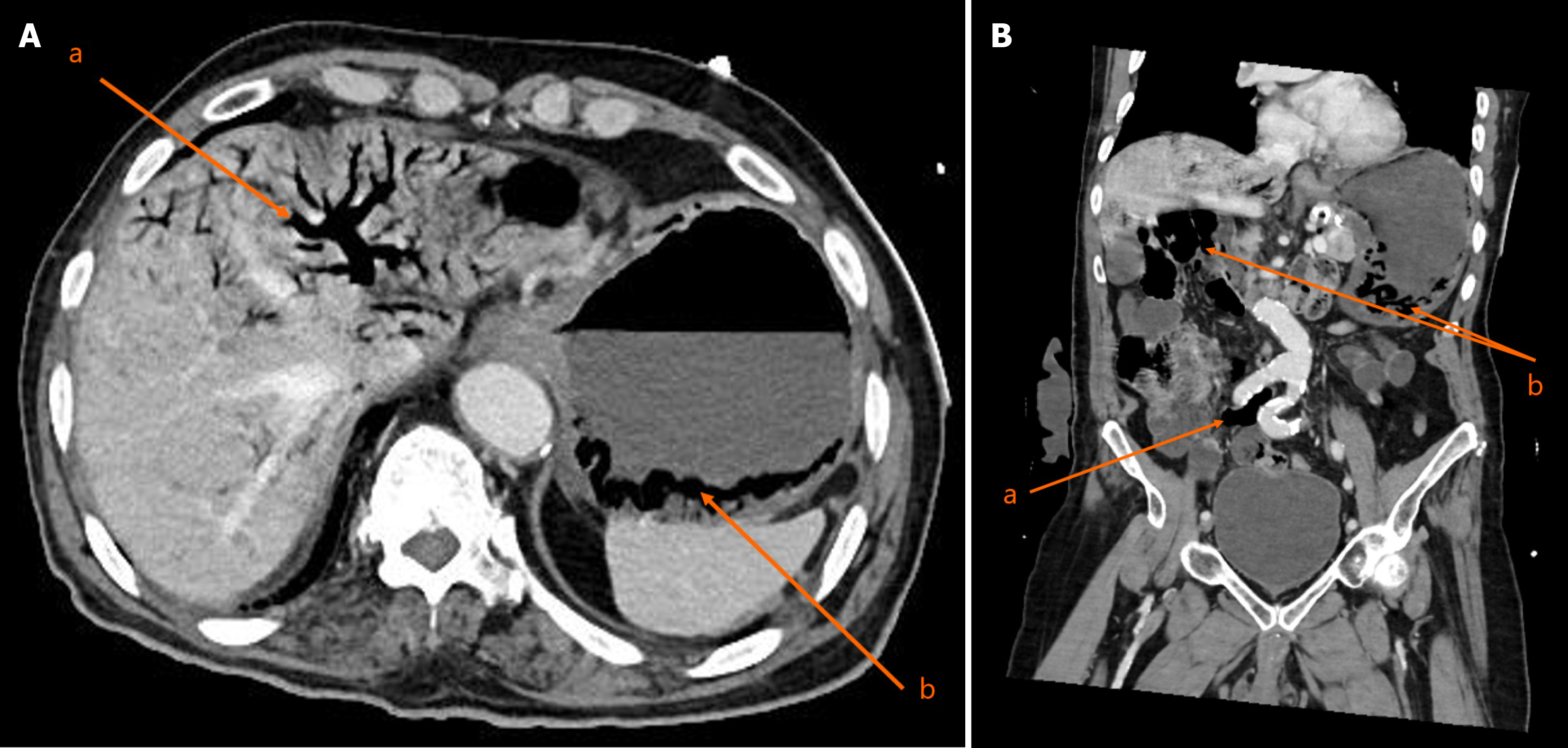

Furthermore, there is no consensus on the preferred imaging modality. However, contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) offers the best information in detecting and evaluating EG. CT classical findings include air within the stomach wall, thickened mucosal folds, and pneumatosis portalis[1,4]. In this case report we presented a challenging case of an elderly male with multiple comorbidities who presented to our emergency department (ED) with non-specific abdominal symptoms. He was diagnosed with EG and was managed conservatively.

An 88-year-old male presented to the ED complaining of epigastric abdominal pain, multiple episodes of vomiting, and a significant increase in stoma output from its baseline.

The patient had the abdominal pain and stoma output changes in the prior 24 h, and the pain became severe enough to seek medical intervention.

The patient had a history of chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage IV, hypertension, dyslipidemia, benign prostatic hyperplasia, diabetes mellitus type 2, and bilateral knee osteoarthritis. Surgical history was significant for exploratory laparotomy, right hemicolectomy with end ileostomy and creation of mucus fistula, and Graham patch repair due to duodenal perforation and hepatic flexure ischemia in 2019 (5 years before this presentation). Ten years prior to presentation the patient underwent laparoscopic left inguinal and umbilical hernia repair.

There was no personal or family history.

Upon assessment the patient was afebrile and hypotensive (blood pressure below 90 mmHg), with epigastric tenderness. Furthermore, the total output of the stoma was maroon-colored, and the nasogastric tube output was similar to coffee grounds.

The patient’s laboratory results in the ED revealed metabolic acidosis with pH of 7.2 and no leukocytosis. Table 1 represents the details of the patients vital and significant laboratory findings upon initial assessment.

| Characteristic | Value |

| Blood pressure | 88/65 mmHg |

| Heart rate | 50 beats/min |

| Respiratory rate | 19 breaths/min |

| Oxygen saturation | 95% in room air |

| pH | 7.2 |

| HCO3 | 17 mmol/L |

| PCO2 | 45 mmHg |

| Lactate | 1.50 mmol/L |

| WBC count | 5.3 × 10-9/L |

| Hemoglobin | 13.5 g/dL |

| Creatinine | 193 μmol/L |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 16 mmol/L |

The patient was resuscitated with isotonic crystalloid, and the decision to proceed with contrast-enhanced CT was made. The CT scan with intravenous (IV) contrast revealed gastric dilatation with decreased wall enhancement and intramural gas along with air in the short gastric veins, extensive pneumatosis portalis, and air in the superior mesenteric vein. However, the arteries were patent. These observations were indicative of EG and possible gastric ischemia. Also, there was a distal ileal short segment wall thickening with decreased enhancement and mesenteric IV gas, representing small bowel ischemia. However, there was no intraabdominal free air or free fluid (Figure 1).

The final diagnosis was EG due to ischemia.

Despite initial resuscitation he was in severe metabolic acidosis: pH 7.12; HCO3 13 mmol/L; pCO2 46 mmHg; and lactate 3 mmol/L. Given these findings we offered the patient and the family surgical exploration with a high risk for morbidity and mortality. However, the patient and his family refused the operative intervention despite the explained high risk of the patient mortality without surgical intervention. Intensive care unit team consultation for admission and close observation was made, given the high-risk condition. The intensive care unit team decided not to admit the patient for the following reasons: (1) He was hemodynamically normal; (2) He did not require any inotropic support; and (3) His care could be managed on the regular surgical floor. We started our management with nil per os, bicarbonate-based fluid for the metabolic acidosis, broad-spectrum antimicrobial coverage with piperacillin-tazobactam and caspofungin, and IV pantoprazole (40 mg twice daily). We consulted with the nephrology team for the optimal fluid option and rate given his CKD background, with the infectious diseases team for broad-spectrum antimicrobial usage, and with the gastroenterology team for the option of diagnostic upper scope, which they recommended against due to the risk of perforation if the stomach was ischemic. On the following day, the patient’s clinical condition improved, the epigastric abdominal pain improved, and he maintained stable vitals. He remained nil per os for 2 days, and his diet was reintroduced gradually.

The patient stayed for a total duration of 6 days with close monitoring in the general ward. Broad-spectrum antimicrobial and bicarbonate-based fluid administration led to the patient’s clinical improvement. Before discharge, his abdominal pain had resolved, stoma output normalized in the amount and color, and his laboratory results improved and returned to his baseline except the hemoglobin level, which was 10 mg/dL. His last blood gas measurement was normal with a normal lactate level. He was discharged in good condition. After discharge he did not come to his outpatient visits. However, he was contacted by phone and reported a good condition with no complaints. After 1 month the patient presented to the ED complaining of hematemesis. The patient was admitted to the ward, and esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed normal mucosa and a stomach ulcer with little bleeding that was controlled.

EG is a rare and severe form of phlegmonous gastritis characterized by the presence of gas-forming bacteria in the gastric wall. The patient’s numerous comorbidities, including CKD, hypertension, NSAID use, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus, combined with a history of bowel ischemia and previous abdominal surgeries significantly increased vulnerability to this condition. The association with ischemia is particularly noteworthy as evidenced by gastric dilatation, pneumatosis portalis, and intramural gas on CT imaging, suggesting an ischemia-induced variant of EG[2-4].

The gastric mucosa normally maintains strong defenses against bacterial invasion through tight intercellular junctions, an acidic pH environment, and efficient vascular circulation. However, these protective mechanisms can be compromised by several factors, including ingestion of caustic substances (corrosives, bases, acids), excessive alcohol consumption, recent abdominal surgeries, gastroenteritis episodes, and NSAID use[5,6]. Our patient displayed nonspecific manifestations including abdominal pain, vomiting, and increased stoma output. Laboratory evaluation revealed metabolic acidosis and hypotension, all nonspecific findings as EG lacks pathognomonic clinical features[7,8]. CT imaging was crucial for diagnosis, demonstrating radiological characteristics consistent with EG[8]. This case illustrated the significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in managing EG in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities.

Currently, no standardized treatment protocol exists for EG. The literature predominantly supports conservative management strategies including bowel rest, broad-spectrum antimicrobials targeting gram positive, gram negative, and anaerobic organisms, and supportive measures[4,9-11]. A comprehensive retrospective analysis demonstrated marked improvement with conservative medical management, with mortality rates decreasing from 60.0% before 2000 to 33.3% afterward[1]. This improvement likely reflects the reduced utilization of exploratory laparotomy[12]. Surgical in

EG is a rare and fatal condition. A high index of suspicion and prompt management is important to avoid fetal con

We would like to acknowledge the patient and his family for their approval to publish this paper.

| 1. | Watson A, Bul V, Staudacher J, Carroll R, Yazici C. The predictors of mortality and secular changes in management strategies in emphysematous gastritis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2017;41:e1-e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Loi TH, See JY, Diddapur RK, Issac JR. Emphysematous gastritis: a case report and a review of literature. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2007;36:72-73. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Nunna B, Parihar P, Dhande R, Mishra G, Gowda H. Emphysematous Gastritis: A Lethal Complication in a Patient With Pancreatitis. Cureus. 2022;14:e32882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Takano Y, Yamamura E, Gomi K, Tohata M, Endo T, Suzuki R, Hayashi M, Nakanishi T, Hanamura S, Asonuma K, Ino S, Kuroki Y, Maruoka N, Nagahama M, Inoue K, Takahashi H. Successful conservative treatment of emphysematous gastritis. Intern Med. 2015;54:195-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Berry WB, Hall RA, Jordan GL Jr. Necrosis of the entire stomach secondary to ingestion of a corrosive acid; report of a patient successfully treated by total gastrectomy. Am J Surg. 1965;109:652-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Clearfield HR, Shin YH, Schreibman BK. Emphysematous gastritis secondary to lye ingestion. Report of a case. Am J Dig Dis. 1969;14:195-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nasser H, Ivanics T, Leonard-Murali S, Shakaroun D, Woodward A. Emphysematous gastritis: A case series of three patients managed conservatively. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2019;64:80-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bak MA, Rajagopalan A, Ooi G, Sritharan M. Conservative Management of Emphysematous Gastritis With Gastric Mucosal Ischaemia: A Case Report. Cureus. 2023;15:e34656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mansour H, Ali J, Swamy A, Leahy A. A Case of Haemorrhagic Emphysematous Gastritis. Cureus. 2024;16:e66084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mackay TG, Phan DH, Mantha PS, Ibrahim HS, Burstow MJ. Conservative Management of Suspected Emphysematous Gastritis. Cureus. 2022;14:e31995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jung JH, Choi HJ, Yoo J, Kang SJ, Lee KY. Emphysematous gastritis associated with invasive gastric mucormycosis: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22:923-927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nemakayala DR, Rai MP, Rayamajhi S, Jafri SM. Role Of Conservative Management In Emphysematous Gastritis. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:bcr2017222118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |